Liberty Matters

Without Value Adding at its Core Economic Theory is Lost

My frustration has continually been that I cannot seem to convey Mill’s vision in a way that others can understand.

My frustration has continually been that I cannot seem to convey Mill’s vision in a way that others can understand.He and the classics did not look at some part of the economy, they looked at all of it all the time all at once. Classical economics is almost all macro with only a touch of micro thrown in where needed. And they looked at the economy in real terms and brought the monetary side into the discussion only at the end.

An economy in the classical literature is the entire national workshop, all of it, all conceived at one and the same moment. Saving was that part of the whole that was devoted to producing capital goods for future productive use. Saving was investment. It could never be anything else.

No one in the interior could know which they were working on themselves. If someone was in the oil industry, they could not know whether what was being produced would end up in the hands of a consumer out for a Sunday drive, or in the hands of a manufacturer producing inputs into some other industry. But they could tell that they were trying to build up the economy’s capital stock, which was what mattered most of all.

Moreover, the way it was looked at was as an economy in motion. There was no equilibrium moment where everything comes to a conceptual halt in some static framework. The economy as conceived was continuously changing and shifting, but also, if things were left to the market, advancing, creating a greater capacity to produce more output. If you read the classics, they are describing the economy we are all familiar with even to this day. Their writings are about economic growth and how to achieve it. They are about raising living standards and creating jobs. It is about actual people doing actual things. It is what you wish modern economics would teach but doesn’t.

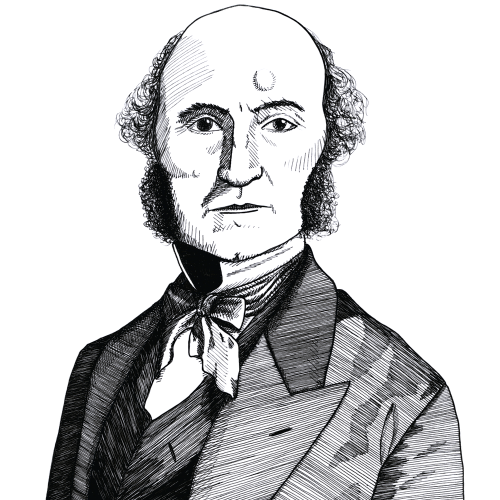

A distinction we no longer make is between productive and unproductive labor. This is a notion we economists now deride since we seem to confuse value adding with utility, something no classical economist did. But productive labor – that is productive effort – in comparison with unproductive labor is the distinction between value-adding and nonvalue-adding activity. It is the distinction that is essential in Mill and the classics generally, perfectly explained in Adam Smith. Let me take you to the opening of Book II, Chapter III of The Wealth of Nations, which should be read in full. There may be more good sense in this chapter than in all the Keynesian-clone textbooks put together. This is from 1776. Where will you find its equal today?

There is one sort of labour which adds to the value of the subject upon which it is bestowed: there is another which has no such effect. The former, as it produces a value, may be called productive; the latter, unproductive labour. Thus the labour of a manufacturer adds, generally, to the value of the materials which he works upon, that of his own maintenance, and of his master's profit. The labour of a menial servant, on the contrary, adds to the value of nothing.[82]

Modern economics thinks of the menial servant in the identical fashion as someone who is working on building an oil rig in the middle of the ocean. Each is just one more employed person earning an income that they can then spend. When we look at Y=C+I+G, we are looking only at final production and completely ignore the hinterland. We never ask, as Smith or Mill did, what the labor was actually producing, nor do we look at an economy’s stock of existing capital assets or whether they are being increased.

I have tried to show my own division in the production possibility diagram in my first post. All economic activities draw down on our existing productivity. Some, however, more than replace what has been taken away, and it is these that allow an economy to move forward.

Productive and unproductive labor, as antique as it might sound, brought the imperative that economic activity in total had to be value-adding to the center of economic theory if it was to create growth and employment. It is the existence of the stock of capital and its increase that allows labor to be employed and real incomes to rise, not the increase in aggregate demand that comes only at the end.

Endnotes

[82.] Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, Book II, Chapter III: "Of the Accumulation of Capital, or of Productive and Unproductive Labour" in An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith, edited with an Introduction, Notes, Marginal Summary and an Enlarged Index by Edwin Cannan (London: Methuen, 1904). Vol. 1.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.