Perspective Essay David Boaz Understood Liberty and the Rule of Law are Inseparable

He has endeavoured to prevent the population of these States; for that purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither….

“You cannot simultaneously have a welfare state and legalize alcoholic beverages.”

If alcoholic beverages are legal, some people will become alcoholics, and become unable to hold down a job. They could end up on welfare. Also, alcoholism often leads to health problems that increase government health care expenditures, in a world where we have programs like Medicaid and Medicare….

"You cannot simultaneously have a welfare state and end the War on Drugs."

Like alcoholism and obesity, drug use often leads to health problems that in turn increase government spending on health care. Plus, some drug addicts end up on welfare because they can't hold down a job.

"You cannot simultaneously have a welfare state and unrestricted reproduction.".

The children of poor people are disproportionately likely to use welfare benefits. Even those from relatively affluent families are likely to consume public education spending

[T]oo many of us who extol the Founders and deplore the growth of the American state forget that that state held millions of people in chains…[I] want to address libertarians who hate slavery but seem to overlook its magnitude in their historical analysis.If you had to choose, would you rather live in a country with a department of labor and even an income tax or a Dred Scott decision and a Fugitive Slave Act?

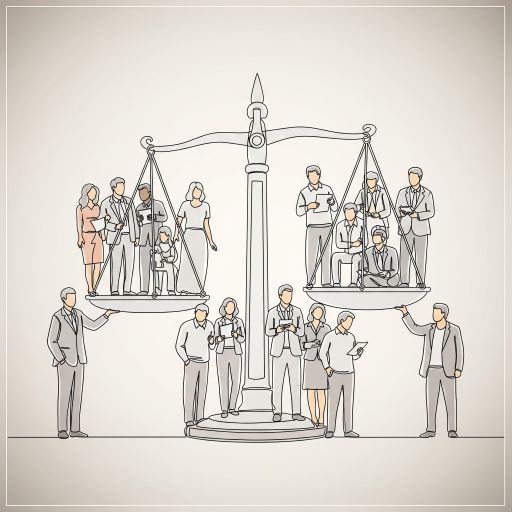

I said that white Americans probably considered themselves free. But in retrospect, were they? They did not actually live in a free society. They were restricted in the relations they could have with millions of their—I started to say "their fellow citizens," but of course slaves weren't citizens—their neighbors. They lived under a despotic power. Liberalism seeks not just to liberate this or that person, but to create a rule of law exemplifying equal freedom. By that standard, even the plantation owners did not live in a free society, nor even did people in the "free" states.

I've probably been guilty of similar thoughtless and ahistorical exhortations of our glorious libertarian past. And I'm entirely in sympathy with [the] preference for a world without an alphabet soup of federal agencies, transfer programs, drug laws, and so on. But I think this historical perspective is wrong. No doubt one of the reasons that libertarians haven't persuaded as many people as we'd like is that a lot of Americans don't think we're on the road to serfdom, don't feel that we've lost all our freedoms. And in particular, if we want to attract people who are not straight white men to the libertarian cause, we'd better stop talking as if we think the straight white male perspective is the only one that matters. For the past 70 years or so conservatives have opposed the demands for equal respect and equal rights by Jews, blacks, women, and gay people. Libertarians have not opposed those appeals for freedom, but too often we (or our forebears) paid too little attention to them. And one of the ways we do that is by saying "Americans used to be free, but now we're not"—which is a historical argument that doesn't ring true to an awful lot of Jewish, black, female, and gay Americans.

requires a restoration of American education, which can only be grounded on a history of those principles that is “accurate, honest, unifying, inspiring, and enobling.’ And a rediscovery of our shared identity rooted in our founding principles is the path to a renewed American unity and a confident American future.

Perhaps the greatest achievement in history is the subordination of power to law…No longer can one man … take another person’s life or property at the ruler’s whim….[Americans] may take the rule of law for granted, but immigrants from China, Haiti, Syria, and other parts of the world know how rare it is.

Limited government is a great achievement, a recent achievement in the sweep of history, and history teaches us that it can be lost. Appreciating where it came from and how rare and fragile it is will help us to preserve it.

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.