Liberty Matters

On Clear Cases of Injustice

Randy’s helpful distinction between constitutional interpretation and constitutional construction helps to make clear that there are two questions we must ask when thinking about how to understand the U.S. Constitution (or any constitution). First, what does the Constitution say; and second, what -- in practical legal terms -- should we do about what it says?

Let’s focus on that second question for now. There are three obvious ways of answering that question which reflect different ways of understanding the relationship between the Constitution and natural justice.

- We ought to implement whatever the Constitution says regardless of the justice or injustice of its principles.

- We ought to implement whatever the Constitution says only insofar asits principles are consistent or can be construed as consistent with justice.

- We ought to implement whatever the Constitution says only insofar as its principles are consistent or can be construed as consistent with justice, or if the unjust intention of the author(s) of the Constitution was expressed with irresistible clearness.

Thankfully, nobody around here seems to be at all interested in option 1. Option 2 seems to be roughly the view expressed by Roderick in his essay. And option 3 is the view that Randy attributes to Lysander Spooner.

My question is: why would anyone ever go for option 3? Option 1 is crazy, of course, but at least, along with option 2, it seems to take a consistent position on the relationship between constitutions and justice. Option 1 says that justice doesn’t matter at all in construing the Constitution. Option 2 says justice reigns supreme -- that the injustice of a construction is always sufficient reason for rejecting it.

Option 3, on the other hand, appears to occupy a kind of wishy-washy middle ground. Basically, it says that we should reject any construction of the Constitution that is inconsistent with natural justice unless the authors were really, really clear that injustice is precisely what they wanted.

Why would anyone ever think this? If natural justice is a good reason to read a vague constitutional phrase in one way rather than another, then why isn’t it also a good reason to ignore, dismiss, or erase phrases that are clearly unjust?

This is especially puzzling when we recall, as Randy reminds us, that construction is a normative enterprise. What we ought to do about the question is a separate question from what the Constitution says. But if constitutional construction is normative, and justice is something close to the supreme normative principle -- a “trump” -- then why should we ever choose to give practical effect to a clearly unjust aspect of the Constitution?

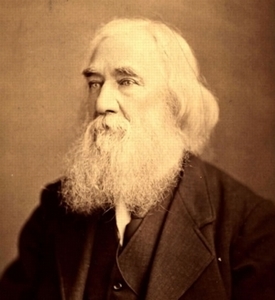

And why would Spooner, of all people, think this? If he really believed, as he said, that "If [the government’s] laws command anything but justice, or forbid anything but injustice, they are themselves unjust and criminal,”[70] then why would he make an exception when the unjust command is expressed without a trace of vagueness or ambiguity?

Endnotes

[70.] Lysander Spooner, A Letter to Grover Cleveland, on his false Inaugural Address, the Usurpations and Crimes of Lawmakers and Judges, and the consequent Poverty, Ignorance, and Servitude of the People (Boston: Benjamin R. Tucker Publisher, 1886). </titles/2224#Spooner_1481_14>.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.