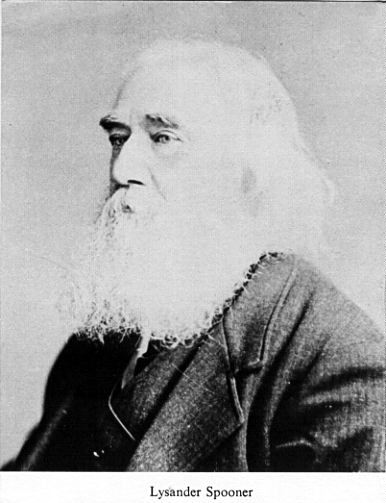

I thank my friends and colleagues Rod Long, Aeon Skoble, and Matt Zwolinski for their very insightful comments on my essay on Lysander Spooner. In some respects, their pieces expand upon mine, which was necessarily limited in what it could cover by a requirement that it be 3000 words and no more. In other respects, however, they register some disagreement.

For example, Rod Long contends that Spooner did not actually change his mind about the Constitution’s authority between 1845, when the first edition of The Unconstitutionality of Slavery was published, and 1870 when No Treason appeared. Although I might contest this claim, I have no interest in prevailing in such an exegetical contest. I would be very content if Spooner had indeed remained consistent in his publicly expressed views. And his correspondence provides reason to believe that Spooner kept some of his views private lest he undermine the appeal of his views on slavery and the Constitution.

Space prevented me from elaborating on two distinctions that might narrow the range of disagreement between Rod and myself, as well as correct a possible misunderstanding of my position expressed by Matt Zwolinski. The first is the distinction between interpretation and construction. The second is the distinction between justice and legitimacy. Both are extensively explained in my book Restoring the Lost Constitution.

Interpretation and Construction

Constitutional interpretation is the activity of identifying the communicative content of the Constitution’s text. Constitutional construction is the activity of giving that communicated content legal effect. Knowing what the words of a constitution means is not the same thing as applying those words to particular cases. And constitutions with no legal effect, like that of the Confederate States of America, still have an ascertainable meaning.

What defines originalism as a method of constitutional interpretation is the belief that (a) the communicative content of the written Constitution was fixed at the time of its enactment, and that (b) this meaning should be followed by constitutional actors until it is properly changed by a written amendment. The first of these propositions is descriptive; the second is normative. In my view, the original meaning of the text provides the law that governs those who govern us; and those who are bound by the Constitution, whether judges or legislators, may not properly change its meaning without going through the amendment process.But why the meaning the text of the Constitution had at the time of its enactment ought to be followed is distinct from ascertaining what that meaning is.

The activity of determining the communicative content at the time of enactment required by the first proposition is

empirical, not normative. Although we can choose to use words however we wish, as Alice discovered in Wonderland, the social or interpersonal linguistic meaning of words is an empirical fact beyond the will or control of any given speaker (which was the point being made by

Alice in Wonderland’s author). As Spooner explained in

The Unconstitutionality of Slavery, “

[I]f the intentions could be assumed independently of the words, the words would be of no use, and the laws of course could not be written.”

[62]

Although the objective meaning of words sometimes evolves, words have an objective social meaning at any given time that is independent of our opinions of that meaning, and this meaning can typically be discovered by empirical investigation. Conducting such an investigation is no more a normative activity to reach conclusions we like than is discovering what is considered good manners in a given society. Say “please” and “thank you”? Shake hands? Bow to someone of higher social status? Wear a veil? We can approve or disapprove of such social practices, and decide whether or not to follow them, but their status as norms is a fact.

So too is linguistic usage. Although I am free to say, “trumetric lyperboly,” I cannot expect that anyone but I will have access to what these two words mean. As an empirical matter, this phrase simply has no objective meaning in our community of discourse. By the same token, I can make up my own meaning for “automobile” as a time machine, but if I decide to use the word to communicate my thoughts in an English sentence, others will take me to be referring to a car.

Where the communicative content of the text provides enough information to resolve a particular issue about constitutionality, giving it legal effect will require little, if any, supplementation, and construction will look indistinguishable in practice from interpretation. That each state is entitled to two senators requires little supplementation to apply. But however much information is contained in the text of the Constitution, there is not always enough information to resolve a particular issue without something more.

To see why this is so, we must understand how language can be either ambiguous or vague. Ambiguity refers to words that have more than one sense or meaning. Vagueness refers to the penumbra or borderline of a word’s meaning, where it may be unclear whether a certain object is included within it or not. Contracts scholar Allan Farnsworth offered this explanation of these two distinct problems of ascertaining linguistic meaning:

Ambiguity, properly defined, is an entirely distinct concept from that of vagueness. A word that may or may not be applicable to marginal objects is vague. But a word may also have two entirely different connotations so that it may be applied to an object and be at the same time both clearly appropriate and inappropriate, as the word “light” may be when applied to dark feathers. Such a word is ambiguous.[63]

In other words, language is ambiguous when it has more than one sense; it is vague when its meaning admits of borderline cases that cannot definitively be ruled in or out of its meaning.

When it comes to resolving ambiguity, the context of a statement usually reveals which sense is meant. For example, the term “arms” in the Second Amendment could be referring to weapons or the limbs to which our hands are attached. Context reveals it to refer to weapons. But even when context reveals the intended sense of a potentially ambiguous word, there is still a problem of vagueness. For example, just how much must an object weigh be before we cease calling it light and call it heavy? How tall must a person be before he is no longer short?

The problem of ambiguity can usually, though not always, be resolved by originalist interpretive method. Even when we are not entirely certain which of the multiple senses of a word or phrase is the intended meaning, historical evidence almost always establishes one meaning as more probable than the others.

Special problems of potentially irresolvable ambiguity can arise either when the evidence of meaning is lost or nonexistent, or when the drafters deliberately injected ambiguity into the text by using euphemisms. This is what the founders did when they referred to slavery by using euphemisms rather than the clear word “slavery,” which they fastidiously avoided including in the text.

[64]

It was the potential ambiguity created by these euphemisms that Spooner exploited when he attempted to identify an innocent meaning of each and every passage of the Constitution that was alleged to have referred to slavery. Having identified an ambiguity, he could then employ his “clear statement” rule of construction, which he borrowed from John Marshall. In my essay, I explain why this argument fails if, in context, the communicated content of the words was not in fact ambiguous, as I believe to have been the case with the offending passages of the Constitution.

In contrast, when it comes to giving legal effect to vague provisions, the terms themselves—

even when interpreted contextually—simply do not contain the information necessary to decide matters of application. What is a “reasonable” search? For that matter, what exactly is a “search”? Is the thermal imaging of a house to detect increased heat caused by marijuana growing in the basement a search?

[65] Because even vague terms have paradigmatic applications lying clearly within the core of their semantic meaning and clearly outside their penumbra, they are not wholly indeterminate. Instead, they are

underdeterminate.

[66] Clear cases of items that are light or heavy, of actions that are a search or not a search, exist.

This is not to say that, when the information provided by interpretation has run out, all decision rules have run out. We could adopt a decision rule that, where a term is vague, it is given its narrowest meaning. Or, in constitutional cases, we could say that, whenever the text is vague, legislatures have a free choice in borderline cases and cannot be second-guessed by judges. But such decision rules are rules of construction, not rules of interpretation. They are rules that apply when the information conveyed by the text itself is insufficient to decide an issue, but the issue still must somehow be decided. They are not found in the communicative content of the written Constitution.

This is exactly how Spooner’s proposed rule of construction operated: “

the court will never, through inference, nor implication, attribute an unjust intention to a law; nor seek for such an intention in any evidence exterior to the words of the law. They will attribute such an intention to the law,

only when such intention is written out in actual terms; and in terms, too, of ‘irresistible clearness.’”

[67]

Spooner is acknowledging here that clearly communicating an “unjust intention” in “actual terms” would be the communicative content of the text. If so, we would still need to decide whether we ought to adhere to that meaning or give it “legal effect.” But when the intention was clearly conveyed, we could not then deny that such was the meaning of the Constitution, which is why Spooner spent so much energy showing that the communicative content of the text was ambiguous. For each of the references to slavery, he found an “innocent” meaning.

Before the traditional distinction between interpretation and construction was reintroduced into constitutional discourse, constitutional scholars and philosophers often indiscriminately called both activities “interpretation.” But because these are two distinct activities, this failure to distinguish them has long caused enormous confusion.

The phrase “just compensation” in the Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment, the example offered by David Lyons and cited by Rod, is more accurately conceived as a vague provision rather than an ambiguous one. The communicative content of the phrase clearly refers to monetary payments to the property owner. The issue is exactly how much compensation is enough to “justly” compensate the owner for the deprivation of his or her property? Just as there are clear cases of “light” and “heavy” objects, there will be clear cases of compensation that is unjustly low or extremely generous. The communicative content of “just compensation,” however, does not itself resolve the matter of borderline cases. Therefore, rules of constitutional construction will be needed to give the Takings Clause legal effect.

Rod focuses on Spooner’s treatment of the term “due” in Article IV’s requirement that persons held to service be “delivered up on claim of the party to whom such service or labor may be due.” Of course, like Lyons, Spooner might be improperly conflating interpretation with construction here, but he need not be read as doing so. Although he might be making a moral realist argument here, Spooner’s own rule of construction eschews such an argument when it concedes that the meaning of the “actual terms” of the text might well be unjust provided that meaning was communicated clearly. For this reason, Spooner then focuses on the innocent meaning of the word “due” to show that it renders innocent the entire sentence in which it appears:

No person held to service or labor in one state, under the laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in consequence of any law or regulation therein, be discharged from such service or labor, but shall be delivered up on claim of the party to whom such service or labor may be due.

But if, at the time it was enacted, the communicative content of this sentence as a whole was taken by all reasonable readers as referring to slavery—then Spooner’s argument about the meaning of “due” fails because the sentence, in context, was neither innocent nor ambiguous.

Legitimacy and Justice

Matt Zwolinski notices my claim that a “legitimate constitution is one that adopts procedures to ensure that the laws that are imposed on the nonconsenting public are likely to be just.” This was an oblique reference to a more extended discussion of constitutional legitimacy in Restoring the Lost Constitution. There, I contended that, if a constitution contains adequate procedures to assure that laws imposed on nonconsenting persons are just (or not unjust), it can be legitimate even if not consented to unanimously, whereas a constitution that lacks adequate procedures to ensure the justice of valid laws is illegitimate even if consented to by a majority.

In my account, there is a “gap” between the justice of a law’s substance and the legitimacy of the law-making procedures that produced it, as well as a gap between a law’s legitimacy and its validity. The concept of legitimacy I have advanced looks to whether the process by which a law is determined to be valid is such as to warrant that the substance of the law is just.

According to my usage, therefore, a valid law could be illegitimate and a legitimate law could be unjust. A law may be valid because produced in accordance with all procedures required by a particular lawmaking system, but be illegitimate because these procedures are inadequate to provide assurances that the law is just. Such a law would not be binding in conscience. A law might be legitimate because it is produced according to procedures that assure that it is just, and yet be unjust because in this case the procedures (which can never be perfect) have failed. Such a law would be binding in conscience unless its injustice was somehow established.

In other words, there is a “gap” between the legitimacy of a law-making system, such as the one established by the Constitution, and the justice of the laws that are produced by this system. This gap is the difference between the actual justice of any particular law and the likelihood that laws resulting from particular procedures are just. Why a law might bind in conscience because it is likely to be just is too involved to fully elaborate here. But consider an analogy.

Consumers presume that the sausages they buy in a grocery store are wholesome and fit for consumption, though they have no personal knowledge that this is the case. They give the sausages the benefit of the doubt. Moreover, their presumption is (or ought to be) based not on the inspection of each and every sausage for wholesomeness, but on the process of sausage manufacturing that, if properly designed, assures that sausages produced this way are highly likely to be fit for consumption and are entitled to the benefit of the doubt. In essence, the perception that the sausages are wholesome is based on faith in the system that made them. But the truth of whether the sausage-making process is indeed “legitimate” is based on whether this faith in the process is rationally warranted.

So too with laws that are produced by a process that ensures their wholesomeness or justice. Like sausages, when laws are made by procedures that assure they are “wholesome,” such laws deserve the benefit of the doubt. There is a duty to obey, not merely because a law was validly made, but because the procedures by which it was made give us reason to believe that such laws do not violate the rights of the nonconsenting persons on which they are imposed. Because this assessment is probabilistic, rather than absolute, the duty of obedience created by such a legitimate law-making process is defeasible or prima facie. Like the sausages purchased in the store, the existence of such a duty may be rebutted by close individual inspection.

As I have explained at greater length elsewhere,

[68] this gap between the concepts of “legitimacy” and “justice” necessitates a refinement of contemporary libertarian theory. A radical libertarian could hold that a legal system is unjust because it confiscates its income by force and puts its competitors out of business by force, but still believe it to be legitimate because the laws it imposes on nonconsenting persons are formulated, applied, and enforced by procedures that assure they are just. In short, an unjust legal system could still be legitimate if it has a good design or “constitution.” But, to return to the distinction between interpretation and construction, to decide whether a legal system that is governed by a written constitution is “good,” one must begin by ascertaining what the written constitution means.

Rod contends that by 1870, Spooner came to question the utility of the U.S. Constitution, as well he might have. As I relate in Restoring the Lost Constitution, after taking constitutional law in law school, I too concluded that the Constitution had failed, because most of its liberty-protective provisions had been ignored. For this reason, when I went into teaching I became a contracts professor.

In my writings I claim only that if it was followed, the text of the Constitution—as it has been amended—would be legitimate in the sense I use that term. I do not claim that the law-making and application system in operation today can impart the benefit of the doubt on the laws it promulgates and enforces. Of course, even if it does not, one may still obey its laws out of a well-justified desire to avoid the costs of punishment for disobedience.

But

our republican Constitution[69] has not been repealed and still means what it says. Most Americans believe that it is the governing document of the United States, which makes it worthwhile to ascertain its meaning and insist that it ought to be followed. This was Spooner’s project in 1845. And such insistence would be consistent with justice even if the regime established by text of the Constitution is in some important ways unjust, and even if, as Spooner claimed in 1870, it did not enjoy the actual consent of We the People, each and every one.

Endnotes

[62.] Lysander Spooner,

The Unconstitutionality of Slavery (Boston: Bella Marsh, 1860), 220.

[63.] E. Allan Farnsworth, “’Meaning’ in the Law of Contracts,”

Yale Law Journal, vol. 76 (1967): 939, 953.

[64.] See U.S. Const. art. I § 2, cl. 3,

amended by U.S. Const. amend. XIV (referring to slaves as “other Persons”); ibid

. at § 9, cl. 1 (referring to slaves as “such Persons” and “each Person”); ibid

. at art. IV § 2, cl. 3 (referring to slave as a “Person[s] held to Service of Labour”). See James McClellan,

Liberty, Order, and Justice: An Introduction to the Constitutional Principles of American Government (3rd ed.) (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2000). <

/titles/679#McClellan_0088_1034>. The specific articles and clauses in "APPENDIX C: Constitution of the United States of America (1787)" <

/titles/679#lf0088_label_092>:

[65.] See, e.g.

Kyllo v. United States, 533 U.S. 27 (2001) (holding that thermal imaging a house from a public vantage point is a search under the Fourth Amendment).

[66.] See Lawrence B. Solum, “On the Indeterminacy Crisis: Critiquing Critical Dogma,” 54

Univ. of Chicago Law Review, vol. 54 (1987): 462, 473 (distinguishing between indeterminacy and underdeterminacy).

[67.] Spooner,

The Unconstitutionality of Slavery, 220

[68.] See Randy E. Barnett, “Libertarianism and Legitimacy: A Reply To Huebert,”

Journal Of Libertarian Studies, vol. 19, No. 4 (Fall 2005): 71-78. <

https://mises.org/library/libertarianism-and-legitimacy-reply-huebert>.

[69.] Randy E. Barnett,

Our Republican Constitution: Securing the Liberty and Sovereignty of We the People (Broadside Books, 2016). Amazon.com: <

http://www.amazon.com/dp/0062412280/ref=cm_sw_su_dp>.

Randy Barnett argues that Lysander Spooner is an important and influential legal theorist. Barnett also explains how Spooner’s work influenced Barnett’s own thinking about how to interpret the Constitution. Since Barnett is himself an important and influential theorist, the first claim is therefore true. QED. But there are more interesting questions, such as why Barnett finds Spooner compelling and whether we should as well.

Randy Barnett argues that Lysander Spooner is an important and influential legal theorist. Barnett also explains how Spooner’s work influenced Barnett’s own thinking about how to interpret the Constitution. Since Barnett is himself an important and influential theorist, the first claim is therefore true. QED. But there are more interesting questions, such as why Barnett finds Spooner compelling and whether we should as well. Lysander Spooner, like many libertarians, believed that individual consent was a necessary condition for political authority. In other words, for a government to have legitimate authority, every single individual living under it must give his or her actual (as opposed to merely hypothetical) consent to it. Since that condition is manifestly not met in the case of the government of the United States – or, I might add, any other government that currently exists or ever has existed – Spooner believed that the government lacks legitimate authority. And this is, no doubt, the correct conclusion to draw from his premises. Once one accepts any version of consent theory strong enough to be worthy of the name, the road to philosophical anarchism is but a short one.

Lysander Spooner, like many libertarians, believed that individual consent was a necessary condition for political authority. In other words, for a government to have legitimate authority, every single individual living under it must give his or her actual (as opposed to merely hypothetical) consent to it. Since that condition is manifestly not met in the case of the government of the United States – or, I might add, any other government that currently exists or ever has existed – Spooner believed that the government lacks legitimate authority. And this is, no doubt, the correct conclusion to draw from his premises. Once one accepts any version of consent theory strong enough to be worthy of the name, the road to philosophical anarchism is but a short one. I thank my friends and colleagues Rod Long, Aeon Skoble, and Matt Zwolinski for their very insightful comments on my essay on Lysander Spooner. In some respects, their pieces expand upon mine, which was necessarily limited in what it could cover by a requirement that it be 3000 words and no more. In other respects, however, they register some disagreement.

I thank my friends and colleagues Rod Long, Aeon Skoble, and Matt Zwolinski for their very insightful comments on my essay on Lysander Spooner. In some respects, their pieces expand upon mine, which was necessarily limited in what it could cover by a requirement that it be 3000 words and no more. In other respects, however, they register some disagreement.

Roderick Long concludes his essay by saying, “I’d also be interested in discussing the relation between Spooner’s and Hayek’s theories of law.” Let’s do that. Here’s Barnett on Spooner again:

Roderick Long concludes his essay by saying, “I’d also be interested in discussing the relation between Spooner’s and Hayek’s theories of law.” Let’s do that. Here’s Barnett on Spooner again:

According to Randy, “If a constitution contains adequate procedures to assure that laws imposed on nonconsenting persons are just ... it can be legitimate even if not consented to unanimously.”

According to Randy, “If a constitution contains adequate procedures to assure that laws imposed on nonconsenting persons are just ... it can be legitimate even if not consented to unanimously.”

I’ve defended Spooner’s claim that normative terms in the Constitution (or any statutory law) should be interpreted as invoking whatever is the objectively correct moral truth, rather than invoking the opinions on morality held by the authors or socially prevalent at the time of its enactment. Let’s call this View A.

I’ve defended Spooner’s claim that normative terms in the Constitution (or any statutory law) should be interpreted as invoking whatever is the objectively correct moral truth, rather than invoking the opinions on morality held by the authors or socially prevalent at the time of its enactment. Let’s call this View A. In my last post I distinguished three positions, in increasing order of radicalism, all of which Spooner defends:

In my last post I distinguished three positions, in increasing order of radicalism, all of which Spooner defends:

Aeon asks: “To rally people to see [an unjust statute’s] lack of authority, is it better to say, ‘That’s not even a law!’ or ‘That’s a bad law’?” And Aeon suggests by way of answer that even if the first approach should turn out to be technically correct, the second approach is a “more effective strategy for mobilizing dissent”; and his reason for this is that those who “go around insisting that the income tax is illegal” are “generally regarded the same way as moon-landing-hoax people or flat-earthers.”

Aeon asks: “To rally people to see [an unjust statute’s] lack of authority, is it better to say, ‘That’s not even a law!’ or ‘That’s a bad law’?” And Aeon suggests by way of answer that even if the first approach should turn out to be technically correct, the second approach is a “more effective strategy for mobilizing dissent”; and his reason for this is that those who “go around insisting that the income tax is illegal” are “generally regarded the same way as moon-landing-hoax people or flat-earthers.”

A couple of addenda to my last post:

A couple of addenda to my last post:

As our conversation on Spooner draws to a close, I’m glad we’ve debated the issues of legal legitimacy in some detail, but sorry we haven’t really explored the breadth of Spooner’s views on other topics. As my final contribution to the discussion, picking up on Matt’s comments on restitution, I want to say just a bit about Spooner’s theory of property rights.

As our conversation on Spooner draws to a close, I’m glad we’ve debated the issues of legal legitimacy in some detail, but sorry we haven’t really explored the breadth of Spooner’s views on other topics. As my final contribution to the discussion, picking up on Matt’s comments on restitution, I want to say just a bit about Spooner’s theory of property rights.