Liberty Matters

On Crisis, Revolution, and Liberty

David Hart has given us an overview of a theory of how classical liberal/libertarian ideas are produced and spread, a suggestion for an intellectual-history project on the subject, and an intriguing taxonomy of different kinds of libertarian approaches to transformation, based on various historical models. As a fellow historian, I was particularly interested in this last aspect of Dr. Hart’s fine essay, and in the short space I have here I want to try to tease out a few points from his remarks that I hope will have some relevance to our current conversation. In particular, I would like to suggest that an atmosphere of crisis seems to play an important role in many (if not most) of the historical examples he provides at the end of his essay. It seems to me that intellectual movements, even those which might seem marginal, or even rather loony, in “normal” times can suddenly emerge as the “obvious” answers to the problems facing a society during times of crisis. In the brief remarks that follow I want to focus on the histories of three revolutions in eastern and central Europe: a revolution that achieved some important successes but ultimately failed to secure political power for the forces of liberalism (the revolutions of 1848); an anti-liberal revolution that succeeded (the October Revolution in Russia); and finally a successful revolution in 1989 that had swept away the communist governments in the region by 1991.

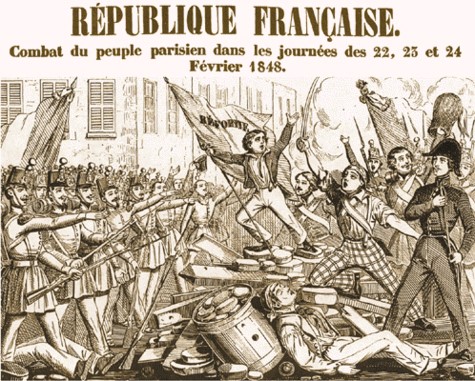

David Hart has given us an overview of a theory of how classical liberal/libertarian ideas are produced and spread, a suggestion for an intellectual-history project on the subject, and an intriguing taxonomy of different kinds of libertarian approaches to transformation, based on various historical models. As a fellow historian, I was particularly interested in this last aspect of Dr. Hart’s fine essay, and in the short space I have here I want to try to tease out a few points from his remarks that I hope will have some relevance to our current conversation. In particular, I would like to suggest that an atmosphere of crisis seems to play an important role in many (if not most) of the historical examples he provides at the end of his essay. It seems to me that intellectual movements, even those which might seem marginal, or even rather loony, in “normal” times can suddenly emerge as the “obvious” answers to the problems facing a society during times of crisis. In the brief remarks that follow I want to focus on the histories of three revolutions in eastern and central Europe: a revolution that achieved some important successes but ultimately failed to secure political power for the forces of liberalism (the revolutions of 1848); an anti-liberal revolution that succeeded (the October Revolution in Russia); and finally a successful revolution in 1989 that had swept away the communist governments in the region by 1991.To start with the earliest of these examples, the 1848 revolutions have usually been considered failures. To paraphrase G.M. Trevelyan’s famous quip, 1848 was the “turning point that failed to turn.” While it is certainly true that the liberals were ultimately defeated by their enemies, they achieved everywhere, but especially in east central Europe, some important and lasting victories. Probably the most important of these, which Dr. Hart mentions in his essay, was the elimination of serfdom in the Austrian Empire in 1848 (actually the culmination of a process begun by Emperor Joseph II in 1781).[25] What were the causes for these successes, and why could the liberals not capitalize on these victories?

Liberal ideas had been circulating in central Europe for at least a couple of decades before 1848, and their promoters had a chance to advance them further due to the exogenous crises created by a string of crop failures all over Europe in the years before 1848. These not only led to rural unrest and to financial difficulties in most European countries but also contributed to the increasing pauperization of the newly emerging industrial working class.[26] The growing social turmoil created the conditions for liberal intellectuals and their allies in most of the European states to try to seize power and establish liberal governments.

The ultimate failure of the east central European liberals was due largely to the fact that they allowed themselves to get sidetracked by another intellectual agenda that ultimately proved to be more powerful: nationalism. Rather than focus on socioeconomic and political liberalization, the members of the revolutionary German government meeting at Frankfurt am Main in the so-called Vorparlament, instead focused increasingly on the establishment of a German constitutional monarchy, and in the process dissipated their energies in endless and ultimately futile discussions about the nature and extent of their envisioned German state

A very important example of a successful, though nonliberal, revolution that Dr.Hart mentions is the October (or November) Revolution of 1917.[27] Does this revolution, paradoxically, have something to say to classical liberals and libertarians? Perhaps, but in any case, this revolution, even more than 1848, owed much of its success to exogenous circumstances and an atmosphere of crisis.

It is important to remember that Russia in the fall of 1917 was already experiencing a revolution. The monarchy had been overthrown in the February (or March) Revolution and the country was being ruled by a shaky provisional government. In this context the Bolsheviks had two important advantages. First, they had an ideology that provided clear overall goals (even if they were vague on the specifics). Part of this ideology concerned the architecture not only of the party itself, but also of the society of the future. Lenin’s main contribution (outlined in his 1902 tract What Is to Be Done?) was his idea of the party not as some sort of proletarian mass-movement, but as a “vanguard” made up of a select, dedicated, group of professional revolutionaries who had mastered the laws of History and could thus steer society.[28]

The second advantage the Bolsheviks had was a politically savvy ability to capitalize on the social and economic catastrophe that was engulfing wartime Russian society. By the fall of 1917 the country’s social and economic fabric was so obviously fraying that the Bolsheviks, in Lenin’s terms, simply “picked up power” that they found “lying in the street.”[29] The October Revolution was really a coup d’etat carried out by Lenin’s small vanguard party against the thoroughly demoralized and weakened Provisional Government.

The Bolshevik revolution was a spectacular success, and the system they established ended up dominating much of Europe, indeed the rest of the globe, by the end of the 20th century. The overthrow of the Soviet empire in the revolutions of 1989-1991 must certainly count as one of the greatest victories for the cause of liberty in history. Where does it fit into the categories provided by Dr. Hart and into the narrative I have been sketching in this essay?

Once again, the success of the revolutionaries involved both the power of ideas and the impact of exogenous crisis. Liberal ideas of various kinds had never been completely extinguished in the lands of “Really Existing Socialism,” especially in the countries of east central Europe. There were always intellectuals, both in and outside the Party, who were familiar with, and attracted to, various aspects of liberalism. Moreover, the people of those countries had front-row seats to the economic development of the (relatively) liberal polities of western Europe, no matter how vigorously their communist rulers tried to disguise or disparage those achievements.

The opportunity for these liberal ideas to find some sort of purchase grew during the late 1980s because of a growing crisis of confidence in the communist parties of the Soviet Union and its satellites. This was in part the result of economic challenges posed by changes in the world economy, but it can also be thought of as a manifestation of the intellectual exhaustion of Really Existing Socialism. This situation made possible the rise of Mikhail Gorbachev to the post of first secretary of the CPSU in 1985.[30] While Gorbachev was no liberal, he was one of a long line of communist leaders who sought to strengthen the communist system by piecemeal introduction of selective liberal reforms, along with a new approach to relations with the satellite countries.

As we all know, these reforms (soon copied with varying degrees of enthusiasm by the communist countries of east central Europe) if anything only made the crisis worse by creating economic and social chaos. They also provided the opportunity for the thus-far thoroughly marginalized and nearly invisible liberals to come out into the open and demand deeper and more extensive reforms. Interestingly, as in 1848, these liberal voices were frequently joined by, or even influenced by nationalist sentiments and demands.[31]

In any case, faced with increasing economic and social disruptions, the communist parties, especially those in east central Europe, found themselves by 1989 in an untenable situation. Unable to count any longer on the military or even the moral support of their comrades in Moscow, the rulers of the different parties were pushed aside by more opportunistic (not necessarily liberal) comrades who were willing to work with the newly empowered liberal dissidents and others demanding constitutional democracy and free-market reforms. This process continued, with many variations of course, until the Soviet Union officially dissolved itself in December 1991.

In all three of these cases a crisis situation created an opportunity for a previously marginalized intellectual movement to make a bid for power. But where exactly this leaves us I am not sure. While “Rothbardian Leninism” might seem to be an attractive strategy, the sort of ruthless discipline and party purity it calls for are hardly compatible with the broader liberal project. On the other hand, the liberal revolutionaries of 1848, though a very mixed bunch with different intellectual agendas, were initially able to win some important victories, only to be blindsided by the power of nationalism. The revolutionaries of 1989, while also espousing a wide variety of views and while also being influenced in varying degrees by nationalism, were apparently able to muster some bare minimum of discipline so that they were able to take power during the crisis years of 1989-1991.[32] I wonder where their strategy fits within Dr. Hart’s taxonomy of libertarian resistance and what if anything it has to teach us?

Endnotes

[25.] Mike Rapport, 1848: Year of Revolution (New York: Basic Books, 2008), pp. 270-71; Robert Kann, A History of the Habsburg Empire, 1526-1918 (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1977), pp. 198-99.

[26.] Rapport, p. 36.

[27.] The revolution occurred in October 1917 according to the old Julian calendar, corresponding to November in the Gregorian calendar.

[28.] Archie Brown, The Rise and Fall of Communism (New York: Harper Collins, 2009), p. 35.

[29.] M.K.Dziewanowski, A History of Soviet Russia and its Aftermath (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Simon and Schuster, 1997), p. 87.

[30.] Archie Brown carefully notes that the “crisis” was “perceived only by a minority of people within the political elite -- those acutely conscious of the long-term lag between the rate of Soviet economic growth and of the technological lag between the Soviet Union and the West … but this was not crisis in the sense that there was significant public unrest.” p. 486.

[31.] Joseph Rothschild and Nancy M. Wingfield, Return to Diversity: A Political History of East Central Europe since World War II (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), p. 175; Peter C. Mentzel, “Nationalism, Civil Society, and the Revolution of 1989,” Nations and Nationalism, vol.18, part 4, October 2012, pp. 624-42.

[32.] Mike Rapport is one of many writers to note the similarities between the revolutions of 1989 and 1848. An important difference is that many of the leaders of the 1989 revolutions “wanted their revolution to be an ‘anti-revolution’” in the sense that “opposition to communism was not about a violent seizure of power, but rather involved elevating the cultural opposition in civil society to greater importance than the repressive state.” p. 414.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.