Liberty Matters

Molinari, Soirées, and Arguing about Liberty

The problem with virtual discussions like the one we have enjoyed over the past month is that we cannot see our interlocutors face-to-face over a glass or two of beer or wine. This is how Molinari imagined it when he wrote Les Soirées de la rue Saint-Lazare in 1849. His interlocutors, the Conservative, the Socialist, and the Economist were supposed to have conducted their vigorous discussions about politics and economics at a party or social gathering in one of the many restaurants or hotels which appeared on Saint Lazarus street near one of the grand Parisian railway stations which ringed the city as the French railway system was being built in the 1830s and 1840s. Molinari chose Saint Lazarus street for his title because it is where he and a small group of liberal friends, which included Frédéric Bastiat, Joseph Garnier, Alcide Fonteyraud, and Charles Coquelin, met regularly between 1844 and early 1848 in the house of Hippolyte Castille which was located on this very street. The friends met regularly between 1844 and early 1848 to discuss political and economic matters, no doubt over a glass or two. This was the inspiration for Molinari’s book.[1]

When Molinari came to write his second collection of Soirées in 1855, this time called “conversations,”[2] the location was no longer the comfortable and up-market surroundings of the residence of an ex-Cardinal in Paris but a working class “estaminet” (the name for a bar or café in Belgium and northern France) in Brussels. After the coming to power of Emperor Napoleon III Molinari had left Paris and taken a teaching position in Brussels where he remained until the late 1860s. Here the conversation takes place between a “Rioter,” a “Prohibitionist” (a strict protectionist), and an “Economist” in a bar close to where a recent riot over food prices had taken place. In a long opening footnote, the Belgian Molinari takes great pains to explain to his Parisian readers the important social place the estaminet plays in Flemish culture and the kinds of drinks which were commonly drunk there. Only once he has established this important information can Molinari then proceed with the “conversations” about freeing up the highly regulated grain trade which in his mind caused the high prices of food which in turn caused the riots.

The third set of Soirées which Molinari wrote in 1886 also set the location of the conversations about liberty in a bar, or rather this time in a series of bars - a new one for each conversation.[3] He updated his debate of 1855 between a “Rioter,” a “Prohibitionist”, and an “Economist” to include a new figure, the “Collectivist,” who replaced the Rioter of the earlier conversations. In keeping with the much darker vision Molinari now had of the prospects for liberty, he set each conversation in an elaborately furnished bar in Paris where he was now living again which was decorated according to a particular theme which he loving describes in his footnotes. In the first conversation the Economist, now visibly grayer than before (Molinari was now 67 years old), sits in a bar called the “Tavergne du bagne” (p. 219) which is decorated on the theme of a penal colony in the tropics; in the second conversation the three meet in a bar called “la Tavergne du Chat-Noir” (the Black Cat Bar) (p. 248) which features a large bust of Molière and waiters dressed as Swiss Guards and Academicians; and the third and final conversation is set in “le café du Rat Mort” (the Dead Rat Café) (p. 274). The only information Molinari gives about this drinking establishment is that it is frequented by local members of the Bourgeoisie, politicians, and aspiring artists. It is in this third and final conversation which takes place in the Dead Rat Café that Molinari comes to agree with the Collectivist that his life’s work of writing and teaching and arguing for liberty had been a complete waste of time. One wonders what the Economist was drinking at this moment of his greatest pessimism and hopelessness.

I relate these stories because it shows that in Molinari’s mind there is a strong connection between the vigorous exchange of opposing ideas and the conviviality provided by good food and drink, and perhaps exotic locations as well. This is something that Liberty Fund also likes to encourage. It also brings to mind an excellent custom which I first encountered after giving a talk on Bastiat at a university in the Bay Area when the formal part of the evening came to an end a decision was immediately made to convene a follow-up meeting of “The Bar Stool Economists” to continue the conversation in a more informal location. I think Molinari and his colleagues attended many meetings of the Bar Stool Economistes in his day. Maybe they were known as “les Économistes de l’estaminet.”

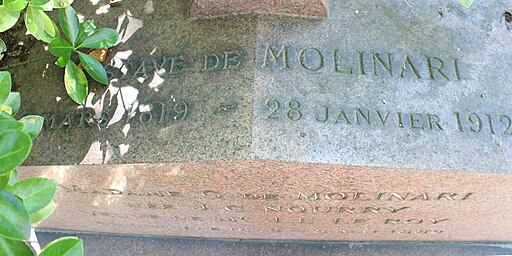

I also wanted to raise the issue of the fluctuating fortunes of classical liberals in the 19th century and how this affected their mood. In 1886 Molinari was certainly very pessimistic as his story of the Soirée in the Dead Rat Café reveals. However hopeless he might have thought his efforts in promoting liberty had been this was certainly not the end of Molinari in spite of his dark vision of penal colonies, black cats, and dead rats. He continued to write and publish for another 25 years resulting in an additional 22 books by my reckoning. I admire his determination and stamina even if I disagree with some of things he had to say. I also admire his clear-sighted realism as his own life was coming to an end on the eve of World War I which was to destroy the liberal order which Molinari had defended and promoted throughout his long life. If I only had one wish it would be to visit Molinari and Bastiat on the streets of Paris in March 1848 so I could help them hand out their leaflets urging the people to support the liberal cause - and then go have a drink with them afterwards so we could continue the conversation about liberty.

I want to thank my contemporary interlocutors for a rewarding month of discussion about an important figure in the classical liberal tradition. May we continue our discussions in an estaminet at some future date.

Endnotes

[1] Gérard Minart, Gustave de Molinari (1819-1912), pour un gouvernement à bon marché dans un milieu libre (Paris: Institut Charles Coqueline, 2012), p. 80.

[2] Gustave de Molinari, Conservations familières sur le commerce des grains. (Paris: Guillaumin, 1855).

[3] Gustave de Molinari, Conversations sur le commerce des grains et la protection de l'agriculture. Nouvelle édition. (Paris: Guillaumin, 1886).

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.