Liberty Matters

Hume and Rousseau on Liberty

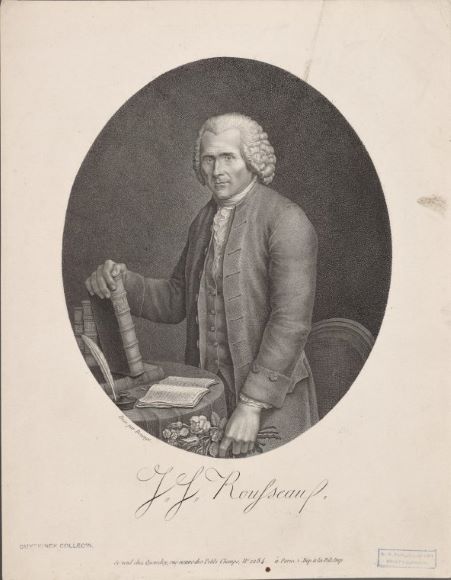

Hume, the skeptical Enlightenment thinker, and Rousseau, the romantic critic of Enlightenment, had a famous falling out, rumors of which spread throughout Europe. The two were bound to clash. The sociable Hume and the solitary Rousseau had significantly different personalities. Their philosophies were also at variance. Hume was an urbane, cosmopolitan defender of civilization. Rousseau lambasted civilization as a corrupter of morals. Their respective conceptions of liberty produced competing ideas about good government and the meaning of progress.

Hume on Two Types of Liberty

In 1762, the Archbishop of Paris condemned Rousseau’s book Emile, which included the “Profession of Faith of the Savoyard Vicar.” Rousseau fled Paris to avoid arrest. Writing to a mutual friend, the Comtesse de Boufflers, Hume wrote, “I am not in the least surprised that [‘The Profession of Faith of the Savoyard Vicar’] gave offence. … The liberty of the press is not so secured in any country, scarce even in this, as not to render such an open attack of popular prejudices somewhat dangerous.”

Although in this passage, Hume seemed to bemoan insufficient liberty of the press, Hume was of two minds about the liberty of the press. Later in life, Hume regarded the liberty of the press as a necessary evil that, while beneficial, tended to rile up the public. But in his early essays Hume highly praised the liberty of the press for allowing “all the learning, wit, and genius of the nation” to “be employed on the side of freedom.” When referring to “freedom” here, Hume likely had two senses of the word in mind: first, free government, and second, personal liberty. The two typically appear in conjunction.

As he stated in his last essay, “Of the Origin of Government” (1777), free government is a mixed government, with divided powers, in which the power of the people is equal to or greater than the power of the monarch. A free government is epitomized by the rule of law, not men. A free government includes frequent elections and institutional restraints on magistrates.

The opposite of a free government is an arbitrary government. As Hume observed in “Of the Rise and Progress of the Arts and Sciences” (1742), an arbitrary government is “oppressive and debasing.” In an arbitrary, or as Hume sometimes described it, a “barbarous” monarchy, the monarch “governs the subjects with full authority, as if they were his own.” The monarch delegates his power to inferior magistrates who exercise discretionary judgment, thereby debasing the people by governing them unequally in accordance with no stable system of law. The people governed in such a manner “are slaves in the full and proper sense of the word.”

Personal liberty consists of the individual’s protection against unreasonable and excessive intrusion into one’s personal affairs. A free government protects personal liberty—the individual’s life and property—by enforcing contracts, ensuring fair trials, and prohibiting unlawful searches and seizures.

A free government secures citizens’ “lives and properties,” exempts citizens “from the dominion of another,” and protects “against the violence or tyranny of … fellow-citizens.” It does so, in part, through the efforts of the popular part of the constitution, the House of Commons, “to maintain a watchful jealousy over the magistrates, to remove all discretionary powers, and to secure every one’s life and fortune by general and inflexible laws.” A person’s liberty is secured when “no action” is “deemed a crime but what the law has plainly determined to be such”; when “no crime” is “imputed to a man but from a legal proof before his judges”; and when “these judges” are “his fellow-subjects, who are obliged, by their own interest, to have a watchful eye over the encroachments and violence of the ministers.”

Liberty, as Hume memorably remarked, is “the perfection of civil society.” Preserving liberty, however, sometimes requires conflict. In fact, free government is characterized by party conflict. There is no way to get rid of it.

Hume on Party Conflicts in Free Governments

Hume located the causes of party conflict in the English Constitution and in human psychology. The monarchical part of the constitution gave rise first to the Cavaliers, then to the Tories. The republican part of the constitution gave rise first to the Roundheads, then to the Whigs. On the psychological level, the former hate and fear anarchy, while the latter hate and fear tyranny.

In his widely read History of England (1754-1762), Hume traced the ultimate victory of the defenders of liberty. The Glorious Revolution of 1688-89, according to Hume, established “a new epoch in the constitution … deciding many important questions in favour of liberty” and giving the “ascendant to popular principles.” As a result, Hume wrote, “we, in this island, have ever since enjoyed, if not the best system of government, at least the most entire system of liberty, that ever was known amongst mankind.”

Hume admitted that it was necessary, both in the English Civil Wars (1642-1651) and the Glorious Revolution, for the popular part of the constitution to oppose the arbitrary and unlawful exercise of monarchical power. According to Hume, even the “wise and moderate”—those averse to tumult and above petty partisan bickering—must admit that the Stuart kings before the Civil Wars were “possessed of so exorbitant a prerogative, that it was not sufficient for liberty to remain on the defensive … it was become necessary to carry on an offensive war, and to circumscribe, within more narrow, as well as more exact bounds, the authority of the sovereign.”

For Hume, the preservation of freedom demands “an eternal jealousy … against the sovereign … no discretionary powers must ever be entrusted to him, by which the property or personal liberty of any subject can be affected.” The need to stoke the fires of this jealousy, these popular passions, to preserve liberty is the reason that “in ancient times” liberty had “been accompanied with such circumstances of violence, convulsion, civil war, and disorder.”

Hume on Liberty, Turbulent and Tranquil

The transition from the absolute monarchy of the Tudors and Stuarts to the limited monarchy of the post-Glorious Revolution settlement made individual life more tranquil and public life more turbulent. In Hume’s words, it rendered “the liberty and independence of individuals … much more full, entire, and secure” and the liberty of the public “more uncertain and precarious.” The reason for this, as Hume acknowledged, is that the preservation of free government demands that the interests of the Crown and the interests of the Commons contend with each other to strike a proper balance between liberty and authority. Although this process preserves an optimal degree of civil liberty, it produces party rage and public strife.

One of Hume’s primary aims was to make not only personal liberty, but also public liberty more tranquil and secure. Private life had become more tranquil with the progress of the arts and sciences. The “middling rank of men,” which Hume called the “best and firmest basis of public liberty,” enjoyed greater levels of commerce and conversation in polite society. And Hume thought public life could become more tranquil, too. Hume noted in “Of the Rise and Progress of the Arts and Sciences” and in “Of Civil Liberty” (1741), that commerce, the arts, and sciences all arose first in free governments. But free governments, at the time Hume was writing, seemed less likely to preserve modern gains in these fields.

Hume vehemently attacked the trend toward excessive freedom in private letters written in the late 1760s and early 1770s. But long before that, in his early essays, Hume had already provided evidence for the benefits of France’s civilized monarchy over Britain’s turbulent mixed government. In “Of Civil Liberty,” Hume had argued that France had learned the right lessons from free governments, combining excellence in the fine arts with burgeoning economic freedom fostered by the rule of law. Hume thought this modernized version of French civilized monarchy would prove more tranquil and, perhaps, more long-lasting than Britain’s mixed constitution, since the latter was threatened by increasing public debt and factionalism.

This argument is consistent with the science of politics Hume articulated not only in his Essays, but also in Book 3 of his Treatise of Human Nature (1740). There, Hume described the origins of law and government. And he contended that government is a means by which to protect the institutions that make a market economy possible, namely, property, trade, and commerce. The purpose of government is to foster free economic competition in society. As Hume stated in perhaps his most optimistic statement about civilizational progress, “industry, knowledge, and humanity, are linked together by an indissoluble chain, and are found, from experience as well as reason, to be peculiar to the more polished, and, what are commonly denominated, the more luxurious ages,” those ages, namely, in which government preserves and promotes commerce.

Rousseau, on the other hand, condemned the more luxurious modern age for fostering slavery, not freedom. Whereas Hume promoted an enlightened, scientific approach to government that fostered greater economic freedom and tranquility, Rousseau detested “our politicians,” who, obsessed with economics, “only speak of commerce and wealth.” For Rousseau, liberty, personal or public, is primarily political. It is anything but tranquil. It requires boldness, action, and vigilance.

Rousseau on How Society Enslaves Us

The primary problem Rousseau addressed in his moral and political writings is the way that society changes the human person. According to Rousseau, the human constitution has been disfigured by generations of social development. Law, habit, and education have pulled us away from our natural, primitive—and for Rousseau, superior—condition.

Having distinguished between primitive and civilized man in his “Discourse on the Origin and the Foundations of Inequality among Men,” Rousseau exclaimed: “How much you have changed from what you were!” One cause of the change in man is the introduction of private property, which created a division between masters and slaves. Rousseau argued that the savage, who does not own any property, is neither master of nor slave of another man. The savage does not know “what servitude and domination are … what chains of dependence can there be among men who possess nothing?” Law itself, according to Rousseau, was created by the wealthy and powerful to retain their position in society.

The other cause of inequality—and dependence—is the fight for distinction, which transforms us from being interested in self-preservation to being interested in gaining social and economic advantage over others. After primitive man, who was “free and independent,” entered society, Rousseau explained, he became a slave to the opinions of other men by trying to appear distinct, uniquely meritorious, in their eyes. Competition and rivalry distorted our self-understanding. We became vain and inauthentic, seeking to please others.

One of the products of the “rage for distinction” was the development of the arts and sciences, which, as Rousseau surprisingly argued in the “Discourse on the Sciences and the Arts,” produced moral corruption. Rousseau thought that Athens illustrated what happens due to great achievement in the fine arts. Athens turned soft, weak, and corrupt. Its rival Sparta, on the other hand, remained rustic, noble, simple, and strong. It would have been better for the Athenians to turn away from their “prideful efforts” and remain in “that happy ignorance in which eternal wisdom had placed us.”

Rousseau’s Social Contract: The Restoration of Freedom

By becoming sociable, man became a slave, forced to live “at another’s discretion.” A free government, according to Rousseau, is one in which freedom—that is, humanity’s native independence—is restored. The purpose of the social contract, for Rousseau, is to return man to a condition of independence, in which he is his own master, setting the law for himself and for society.

But the people themselves must act to restore freedom, which Rousseau called “the most noble of man’s faculties.” The people must value freedom over tranquility. The people must desire freedom more than gain. The people must fear slavery more than poverty. This robust love of freedom requires emulation of ancient model republics, such as Sparta and Rome.

On the individual level, this means that citizens should “despise European voluptuousness” and, like “naked savages” regain the willingness to “brave hunger, fire, the sword, and death to preserve nothing but their independence.” It might seem hopeless to expect modern citizens addicted to tranquility and luxury to exhibit the strength, courage, and vigor of soul belonging to primitive man. But Rousseau supposed that a small, well-governed democracy might generate enough public spirit, enough love of the fatherland, to enable citizens to live freely in the modern world.

Rousseau argued that a legitimate government is a republic ruled by the general will. In such a republic, Rousseau wrote, “you have no masters other than those wise laws you have made, administered by upright magistrates of your choosing.” Freedom in this republic exists when there is “perfect independence with respect to all the others” and equal dependence of all on the state, which enforces the general will, the will of the people expressed in the framing of fundamental law.

Competing Visions of Liberty and Progress

Hume’s influential theory regarding the possibility of an extended commercial republic provided the framers of the American Constitution with the tools to craft a large federal republic. Rousseau, on the other hand, insisted that republics, like those of the ancient world, must be the right size, neither too small nor too big. They must be big enough that they can be self-sufficient, but not so big that they cannot be well-governed.

The difference between Hume and Rousseau on this point stems, in part, from Hume’s attempt to find the institutional means by which to prevent faction from tearing government apart. Rousseau, however, thought that independence required that individuals make laws for themselves. Rousseau thought that “the more the state grows, the more freedom diminishes,” because the individual makes up less of the sovereign power.

Free government, for Rousseau, is based on laws that are responsive to the general will. Free government, for Hume, protects life and property in a freely competitive market. For Rousseau, man is very much a political animal. For Hume, man is very much an economic animal. This is one reason why Hume thought efforts by the government to reduce material inequality were ultimately feckless and possibly unjust. The end of government, for Hume, is the protection of free exchange in civil society, not the attempt to establish a desirable end-state, for example, the redistribution of wealth according to some predetermined standard.

Rousseau, meanwhile, argued that government ought to be responsive to the general will. For this to happen, property ownership and wealth distribution must be relatively equal. If citizens are too poor, they might sell themselves. If citizens are too rich, they might attempt to buy others. For Rousseau, sumptuary laws and limits on wealth accumulation are necessary to preserve political independence.

Hume viewed progress as the result of free exchange of goods, services, and ideas in civil society. This produces advancement in the mechanical and liberal arts. Rousseau thought this kind of “progress” weakened man’s political muscles, making him morally lax, undisciplined, and dependent on representatives in parliament. Rousseau argued that a truly free republic calls for constant attentiveness to public affairs, because man is most free when he lives by his own law.

To prefer private wealth and tranquility over disciplined participation in public life is to renounce one’s freedom. And “to renounce one’s freedom,” according to Rousseau, “is to renounce one’s quality as a man.” Quoting Stanislaw Leszczynski, King of Poland, Rousseau declared: “I prefer dangerous freedom to quiet servitude.” Hume, meanwhile, sought to make freedom less dangerous.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.