Liberty Matters

The Storytelling of Hume and Rousseau

I am grateful to have been included in this Liberty Matters conversation on conceptions liberty in David Hume and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. My colleagues’ contributions are well-written and thought provoking.

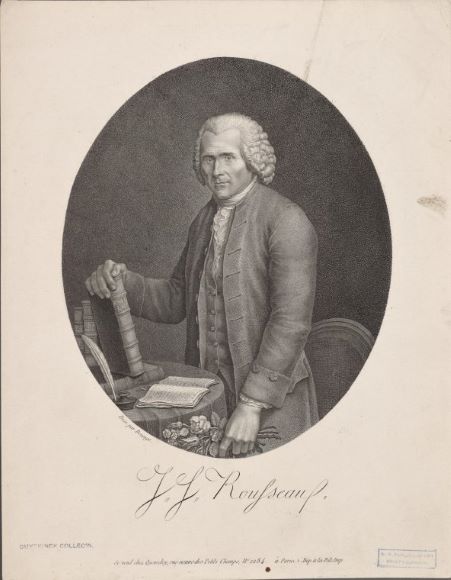

It is helpful to think about this subject in terms of storytelling. Edward J. Harpham does an excellent job relaying the stories Hume and Rousseau tell about liberty and modernity. As Harpham observes, Rousseau’s conception of liberty arises from his conjectural history of the origin of inequality in his Second Discourse. Hume’s conception of liberty, meanwhile, arises not only from his conjectural history of the origin of justice and society in Book 3 of the Treatise, but also from his History of England. Although this history is grounded in past events, it is, as Hume noted, written in the same “philosophical spirit, which I have so much indulg’d in all my writings” (Letters of David Hume, 1:193).

Edward Harpham and Maria Pia Paganelli effectively highlight the central issue of dependence in modern commercial society. A commercial society, as Paganelli notes with reference to Smith, is a society in which each person is a merchant. It is also, I might add, a society in which all social arrangements tend to be regarded as mutually beneficial exchanges between self-interested individuals. Specialization in modern commercial society leads to what Smith called “the division of labor” and Hume called “the partition of employments.” Hume and Rousseau tell stories about the origin of commercial society. And they theorize about what can be done to secure liberty within it. Whereas Rousseau emphasized the costs of commercial society, Hume emphasized its benefits. Paganelli is right about this.

Interestingly, Paganelli writes that Hume and Rousseau differ in their “understanding of the role of reason in the political realm.” Paganelli simply did not have space to address the role of reason in the philosophies of Hume and Rousseau. But it would be helpful to elaborate on the differences here. As Hume famously stated in the Treatise, reason is the slave of passion. From his point of view, the development of justice and society, of political and economic institutions, is due not to the exercise of reason but to a combination of trial-and-error, historical contingency, and individual agency. Hume thought that conceptions of justice, virtue, and vice arise organically from the “intercourse of sentiments” in “society and conversation.” This “intercourse of sentiments” results from the operation of sympathy, a psychological mechanism that enables us to feel the pleasures and pains of others (see T 3.3.3.2).

For Rousseau, on the other hand, peace, security, and liberty in society are best assured when individuals can ascertain and submit to the General Will. This requires deliberation. Deliberation, as Harpham writes, requires that individuals are “sufficiently informed.” He also mentions that, according to Rousseau, “there must be no communication among citizens in thinking about the public good.” For Rousseau, then, strict moral discipline and political participation among relative equals within a small republic is necessary to promote the common good. This requires more independent ratiocination about the meaning and purpose of justice than Hume allows for.

Still, both thinkers are fully modern, arguing that the opinion of mankind legitimates political authority. In the Treatise (3.2.9.4), Hume argues that the opinion of mankind is “infallible” regarding all moral and political matters. And Rousseau, in the Discourse on Political Economy, adheres to the dictum that the voice of the people is the voice of God.

I think Zeng relies too much on Sagar, insofar as she thinks that Hume, who tells the story of the development of modern liberty in Great Britain, defines liberty in an historically contingent and culturally relative way. Zeng contends that Hume “never attempted to explicitly define the idea of liberty.” She does not actually mean this, of course. Later in her essay, she writes that “Hume’s emphasis on opinion demonstrates the power of ideas.” And, again, she suggests that “Hume would not deny that liberty means to be free from domination.” Hume did, then, have an idea of liberty. And he thought he could compare levels of liberty existing across cultures.

In his essay, “Of Civil Liberty,” Hume contrasted “civil liberty” with “absolute government.” The latter is arbitrary. It depends on the judgments of magistrates, rather than equal laws. Hume argued that “all kinds of government, free and absolute, seem to have undergone, in modern times, a change for the better.” He thought so because of the high level of civil liberty present in both Great Britain’s mixed government and France’s civilized monarchy. Referring to France’s civilized monarchy, Hume wrote, “Property is there secure; industry encouraged; the arts flourish; and the prince lives secure among his subjects, like a father among his children.”

For Hume, civil liberty is not confined to free governments. In fact, Hume thought “monarchical governments” showed greater prospects for improvement in this area than “popular governments.” He criticized the French monarchy for its “unequal, arbitrary, and intricate method of levying” taxes. This dampened industry and agriculture and advantaged the landed nobility. But this could easily be corrected, Hume noted, by the reformation of tax policy. The popular government of Great Britain, meanwhile, was drowning in public debt, which Hume thought would “curse our very liberty” and reduce British subjects to “servitude” through a “multiplicity of taxes” and an “inability for defense.” It would be far worse, Hume indicated, to live in servitude in a republican government than to live freely in a civilized monarchy. Equal laws matter most of all. And it does not matter, according to Hume, if you—as citizen or subject—are the author of those laws.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.