Liberty Matters

Rousseau and Hume on Liberty: Reflections on the Essays by Paganelli, Zubia, and Zeng

The four essays in this symposium reveal how complex and multilayered the ideas about liberty are in the work of Jean Jacques Rousseau and David Hume. My own contribution focuses on the different stories about liberty told by Rousseau and Hume about the unfolding of liberty in history, and the role played by exchange, markets and commerce in bringing liberty to the modern world.

Paganelli’s discussion is more narrowly targeted, centering around the pivotal role that the idea of a commercial society plays in their respective views of liberty. While Rousseau and Hume share some common ideas, such as a belief in the importance of equality before the law and the mutual dependency that results from an intensifying division of labor, she recognizes the gulf that separates Rousseau’s views from Hume’s. For Rousseau, commerce may bring wealth and prosperity to the modern world, but also material inequality and psychological misery as people lose their natural independence. In contrast, for Hume commerce brings industry and material wealth to humankind. Rather than cultivating dependency, commerce alleviates material misery and promotes human sociability, making society freer in the process.

Zubia’s and Zeng’s response essays take different tracks for understanding the differences between Rousseau and Hume on liberty. Zubia focuses on the distinction between the ideas of personal liberty and of a free government. Here Zubia draws a sharp line between Hume and Rousseau. Hume argues that personal liberty means that an individual should be protected “against the unreasonable and excessive intrusion into one’s personal affairs.” Free government protects one’s personal liberty through “enforcing contracts, ensuring fair trial, and prohibiting unlawful searches and seizures.” Zubia argues that this differs sharply from Rousseau’s notion of a free government based on laws responsive to the general will.

Zeng’s essay echoes many of Zubia’s concerns, drawing attention to the difference between Rousseau’s analysis which is rooted in the natural law tradition and Hume’s which is integrated into an analysis of English constitutional history from Roman times to the present. She argues that Rousseau “makes an original contribution to the question of liberty and authority by associating liberty with the idea of popular sovereignty.” The end of her essay raises important questions. What are the dangers of associating liberty with popular sovereignty? Can Rousseau’s notions of liberty and sovereignty be reconciled with Hume’s notions of personal liberty and free government or are they forever in tension with one another?

Taken together, these essays point to the importance of understanding the differences between Rousseau and Hume on the question of liberty. But the essays in their current form don’t go far enough in discussing the practical implications of their notions of liberty. In the end, I believe that Rousseau and Hume present starkly different visions of what freedom means in the modern world.

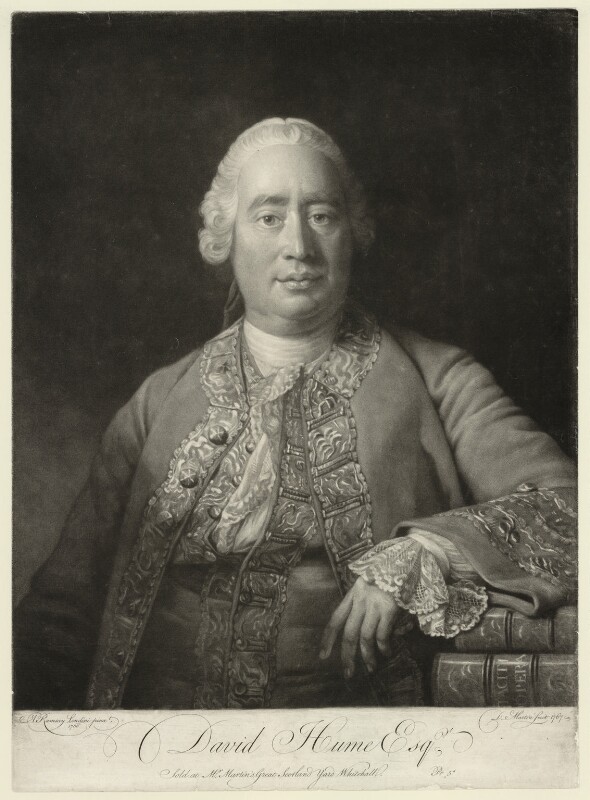

Throughout his writings, David Hume stresses the role that sociability plays in human affairs. For Hume, there is no denying that fundamentally we are separate self-interested individuals with our own unique sentiments, passions, tastes, and drives. We experience the world differently, coming to value different things and ideas. But we grow up and live in human communities where we are socialized and educated to care about our own needs and wants alongside the wants and needs of others. By nature, we are sociable creatures who learn to cultivate and refine this sociability in beneficial ways, both individually and collectively. The story of liberty in human history is one of overcoming our natural condition of isolation and learning how to work together for our own good and the common good. Language, morality, government, law, technology, and the like are inventions that make the natural world a more commodious place for humans to live and find happiness as we best conceive it. Hume's analysis sets the stage for thinking about how best to foster institutional mechanisms for promoting material and emotional prosperity and enhancing human sociability.

There is considerable irony in the fact that Rousseau is often portrayed as the great defender of sociability and other communitarian values because his notion of freedom is an odd one, based upon contentious philosophical ideas about freedom and history. What Hume sees as evolving sociability and progress, Rousseau sees as intensifying slavery and corruption. Rousseau’s General Will is his imagined solution to this slavery of dependence on the wills of others. Being authorized by the impartial and independent wills of all properly educated citizens, the General Will is supposed to be the vehicle by which we can be free while living with others in a complex society. Significantly, the General Will is discovered not through the bargains and compromises of self-interested individuals in a real-world political process but through meditative self-introspection of properly educated citizens on what is in the public good. What if we as individual citizens do not grasp this General Will? What if we as individuals cannot reach a mutual understanding of what public utility is or why we might have to sacrifice our own private good to this public utility? Rousseau’s answer is disturbing. Society has the right and the power to coerce citizens into obedience. As Rousseau so succinctly puts it, in order that the social compact is not an empty formula, citizens can be “forced to be free.”

From the perspective of the eighteenth century, this notion of forcing people to be free might simply be seen as a rhetorical flourish to embellish an idealistic political theory about freedom. From the perspective of people who have lived through the totalitarian nightmares of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, another conclusion is in order. Flawed ideas about the nature of freedom can carry with them disastrous consequences in the real world. Forcing people to be free through Rousseau’s idea of the General Will is bad in theory and worse in practice.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.