Liberty Matters

Frederick Douglass and Liberty

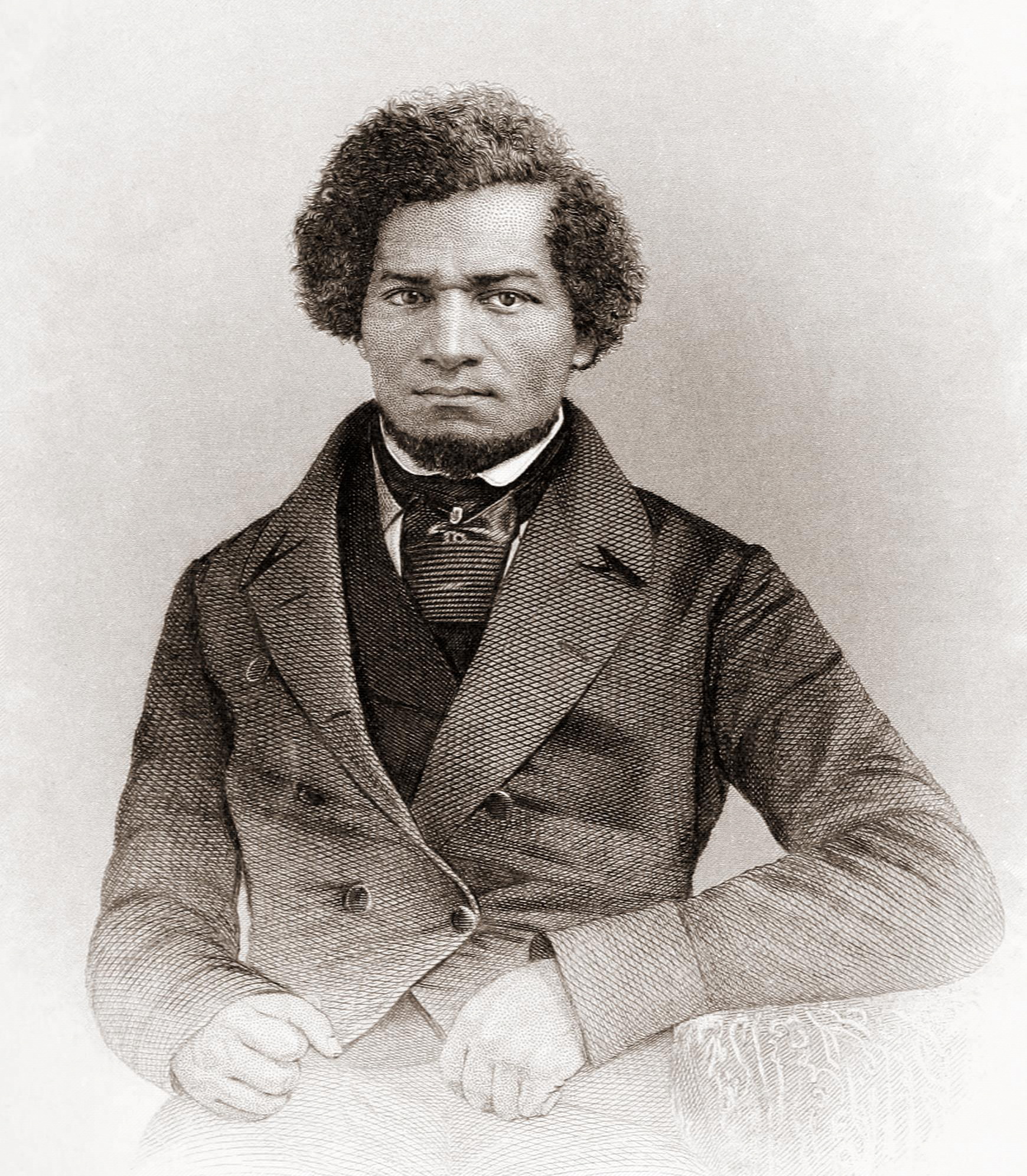

More than a century and a quarter after his death, Frederick Douglass remains America's best known antislavery spokesman. An escaped slave himself, and author of one of the nation’s great autobiographies, he was a brilliant intellectual and activist, who will forever be remembered as one of the immortal champions of those in bondage.

What’s less well known are Douglass’s broader libertarian commitments. He went beyond arguing for emancipation, to advancing a program of economic liberty, private property rights, the right to possess firearms, and other freedoms that in today’s parlance are associated with “conservatism”—while also advocating for women’s suffrage, interracial marriage, and the rights of immigrants, all of which are typically labeled “liberal.” In short, like any good libertarian, Douglass would have rejected today’s alleged dichotomy between “personal” and “economic” liberty. He saw these as merely different facets of the individualism that animated all his concerns.

While he supported efforts at social reform, he saw that reform by compulsion was a fool’s errand. Thus he rejected socialism—which was becoming increasingly popular among intellectuals in his lifetime—calling it “arrant nonsense” to contend that “holding property in the soil” was “on the same footing as holding property in man.”[1] With remarkable prescience, he told a friend that because a socialist state would obliterate the profit motive, it could only produce wealth through compulsory labor, which meant (in the friend’s words) that socialism would “necessarily resemble slavery in its cruelties as well as in its privations.”[2]

What’s more, economic liberty was central to Douglass’s thinking. When Union general Nathaniel Banks, occupying New Orleans in 1865, forbade freedmen from taking jobs without his permission—supposedly to protect them from being exploited by their bosses—Douglass denounced the idea. “What is freedom? It is the right to choose one’s own employment…. When any individual or combination of individuals undertakes to decide for any man when he shall work, where he shall work, at what he shall work, and for what he shall work, he or they practically reduce him to slavery.”[3] When asked what the government should do to help the freed slaves, his answer was: “Do nothing with us! Your doing with us has already played the mischief with us. Do nothing with us…! If the Negro cannot stand on his own legs, let him fall also. All I ask is, give him a chance to stand on his own legs! Let him alone!”[4]

Douglass’s advocacy of economic freedom, private property rights, and the right to possess firearms were of a piece, because the bedrock of his political orientation was that the individual owns him- or herself. This has been the foundation of classical liberal political philosophy since at least the days of John Locke, who had argued in the seventeenth century that because each person is a self-possessor, each has a right to his own labor, and consequently to the fruits of his labors—and that this self-ownership principle also necessarily implied representative government, because if each person owns his own faculties, government may never justly assert power to rule without asking permission first.

The Declaration of Independence—which practically served as scripture to the abolitionists—phrased this idea in almost syllogistic terms: All people are equally born free; this means we have the right to guide our own lives, and that the only legitimate government is one based on consent—and also that there are certain lines government may never justly cross. The same moral principles that bar murder or theft by individuals also constrain the state, because we cannot ask government to murder or steal on our behalf.

This explains why the American founding fathers, laboring in Locke’s shadow, understood and admitted that their principles were incompatible with slavery. And by 1807, when outgoing president Thomas Jefferson signed a federal law banning the international slave trade, they had reason to hope slavery was already fading away. All Northern states abolished slavery between 1780 and 1804, and they thought economic pressures would do the rest, given that slavery was enormously wasteful.

What they did not foresee was the rise of technology that made slavery far more profitable and the advent of an explicitly anti-liberal political philosophy—indeed, the first anti-capitalist political ideology in American history, now known as the “positive good school.” Led by such figures as John C. Calhoun, Henry Hughes, George Fitzhugh, and James Hammond, this school argued that liberalism and capitalism are soulless, artificial, and spiritually bankrupt, because they are premised on calculating reason and vulgar selfishness, instead of the supposedly more “human” considerations of companionship and belonging that animated slavery.

In his Letters on Southern Slavery (1845), Hammond contrasted slavery with capitalism by arguing that the former was a “sacred and natural system in which the laborer is under the personal control of a fellow being endowed with the sentiments and sympathies of humanity,” whereas capitalism, or the “modern artificial money-power system,” was “cold, stern, [and] arithmetical.”[5] Fitzhugh was more explicit in his Sociology for the South (1854). The “whole philosophy, moral and economical, of The Wealth of Nations,” he wrote, is “‘Every man for himself, and Devil take the hindmost’”[6]—whereas slavery was about “protective care-taking and supporting”—indeed, it was “the very best form of socialism,” because it was grounded in the compassionate hierarchy of paternalism.[7]

It was against this anti-capitalist, anti-liberal doctrine that Abraham Lincoln spoke in 1859 when he said that economic freedom is “the just and generous, and prosperous system, which opens the way for all—gives hope to all, and energy, and progress, and improvement of condition to all.”[8] The freedom to pursue happiness by employing one’s skills to provide for oneself is the very opposite of “cold” and “stern”—it is both essential to individual liberty and the key to social advancement. And it stood in humane contrast to the paternalistic and static collectivism advocated by the positive good school.

Douglass could affirm Lincoln’s arguments with his own experience. After escaping slavery in 1838, he had traveled to Massachusetts—only to find that he was free, as he put it, “from slavery, but free from food and shelter as well.”[9] He soon found an opportunity, however:

The fifth day after my arrival I … went upon the wharves in search of work. On my way down Union Street I saw a large pile of coal in front of [a] house…. I went to the kitchen-door and asked the privilege of bringing in and putting away this coal. “What will you charge?” said the lady. “I will leave that to you, madam.” “You may put it away,” she said. I was not long in accomplishing the job, when the dear lady put into my hand two silver half-dollars. To understand the emotion which swelled my heart as I clasped this money, realizing that I had no master who could take it from me—that it was mine—that my hands were my own, and could earn more of the precious coin—one must have been in some sense himself a slave…. I was not only a freeman but a free-working man, and no master … stood ready at the end of the week to seize my hard earnings.[10]

This helps explain why economic freedom was as critical for Douglass as freedom of speech or religion.

Despite his clear words, Douglass’s legacy was later appropriated by the political left, which sought to downplay elements of his political philosophy, such as his support for the U.S. Constitution (in opposition to abolitionists who argued that the constitution was a pro-slavery document), and his skepticism toward labor unions (which excluded black Americans from membership, and thus deprived them of employment opportunities[11]). Some scholars, such as Waldo Martin Jr., openly denounce Douglass’s pro-free market views,[12] but others take a subtler approach, arguing that Douglass was either unaware of the “fact” that government intervention is necessary for racial equality, or that he was really not a proponent of laissez-faire at all.

The dispute over Douglass’s legacy is most notable with respect to his famous “leave us alone” speech. Scholar Nicholas Buccola has argued that Douglass came to regret these words, and to endorse interventionist government policies to aid black Americans in attaining equality.[13] He cites an 1880 speech in which Douglass said that if the country had followed the advice of such leaders as Thaddeus Stevens and Charles Sumner—who wanted to confiscate land from Southern whites after the Civil War and redistribute it to blacks—“the terrible evils from which we now suffer would have been averted.”[14] This, Buccola argues, shows that Douglass’s views about private property had “evolved.”

Actually, as I’ve shown elsewhere,[15] this is not an accurate reading of Douglass’s 1880 speech. For one thing, he explained that his “do nothing with us” speech had been misunderstood. “I meant all that I said [in that speech],” he later said. But it was not “doing nothing” for states to exclude black Americans from public schools or voting or economic opportunity. “Should the American people put a school house in every valley of the South and a church on every hill side and supply the one with teachers and the other with preachers, for a hundred years to come, they would not then have given fair play to the negro . . . . The nearest approach to justice to the negro for the past is to do him justice in the present. Throw open to him the doors of the schools, the factories, the workshops, and of all mechanical industries. For his own welfare, give him a chance to do whatever he can do well. If he fails then, let him fail! I can, however, assure you that he will not fail.”[16]

These words hardly show that Douglass came to reject his earlier commitment to classical liberalism. Rather, he understood that the problems with racism were far more complicated than the type of problems that can be solved by the adoption and enforcement of legislation—and that the latter path held serious dangers for a persecuted minority. As public choice scholars have demonstrated, government intervention merely transfers the operative decision-making power from the hands of private buyers and sellers into the hands of politicians and bureaucrats, who typically base their decisions on political factors rather than on merit or economic efficiency. Thus wealth redistribution tends to reward the politically well-connected at the expense of the already disfavored. This explains why minorities tend to stagnate economically under redistributive government—and why the early twentieth century Progressive movement simultaneously expanded government power and implemented segregation.

Douglass died before that happened and before economists devised the tools to explain the deleterious consequences of government intervention. But he did detect that danger—which explains why Douglass advanced what looks today like an unusual argument for the right to vote. He was a vigilant champion of voting rights, but unlike those today who see voting as a way to mold society toward a desired end, Douglass viewed the ballot as a tool of self-defense. “While the black man can be denied a vote, while the Legislatures of the South can take from him the right to keep and bear arms … the work of the Abolitionists is not finished,” he declared a month after the Civil War ended. “Slavery is not abolished until the black man has the ballot.”[17] Nearly 30 years later, his message remained the same: “Those who are already educated and are vested with political power have thereby an advantage which they are not likely to divide with the Negro, especially when they have a fixed purpose to make this entirely a white man’s government.”[18] The right to vote was critical to prevent state governments from effectively re-instituting slavery—or, as Douglass put it, from “establish[ing] an ownership of the blacks by the community among whom they live”[19]—which, in fact, Southern state governments effectively accomplished not long after his death.

Some scholars of the Reconstruction Era have claimed that “free labor ideology” (which views the right to economic liberty as a crucial element of freedom) was an advent of the post-Civil War era. But Douglass’s career reveals that the age-old principles of classical liberalism that animated the American founding were always the essential core of anti-slavery and then of laissez-faire thinking in the nineteenth century—and that they remain essential to any program of “true anti-racism” today.

Endnotes

[1] Frederick Douglass, “Property in Soil and Property in Man,” Nov. 18, 1848, in Philip Foner, ed., The Life and Writings of Frederick Douglass (New York: International Publishers,1975), vol. 5, p. 105.

[2] Frederic May Holland, Frederick Douglass: The Colored Orator (Toronto: Funk & Wagnalls, 1891), 92.

[3] Douglass, “What the Black Man Wants,” Apr. 1865, in Foner, ed., Life and Writings, vol. 4, p. 158

[4] Ibid., 164.

[5] Gov. Hammond’s Letters on Southern Slavery (Charleston: Walker & Burke, 1845), 27-28.

[6] George Fitzhugh, Sociology for the South, or the Failure of a Free Society (Richmond: A. Morris, 1854), 10.

[7] Ibid., 28

[8] Speech at the Wisconsin Agricultural Fair, Sep. 30, 1858, Don E. Fehrenbacher, ed., Abraham Lincoln: Speeches and Writings (New York: Library of America, 1989), vol. 2, p. 98.

[9] Douglass, The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (London: Christian Age, 1882), 172.

[10] Ibid., 177.

[11] https://frederickdouglasspapersproject.com/s/digitaledition/item/18429

[12] Waldo E. Martin, Jr., The Mind of Frederick Douglass (Raleigh: University of North Carolina Press, 1986).

[13] Nicholas Buccola, “You Can’t Put Frederick Douglass in Chains, N.Y. Times, Mar. 12, 2018,

[14] Frederick Douglass, “Suffrage for the Negro,” Frederick Douglass on Slvery and the Civil War: Selections from his Writings, 58

[15] Timothy Sandefur, “Did Frederick Douglass Change His Mind? And If So, So What?” In Defense of Liberty, Apr. 20, 2018, https://www.goldwaterinstitute.org/did-frederick-douglass-change-his-mind-and-if-so-so-what/.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.