Liberty Matters

Where Do We Go From Here?

Rachel Ferguson and Marcus Witcher have done more than argue that economic freedom, property rights, and other classical liberal values are and always have been indispensable to any effort by black Americans—or, indeed, any racial minority—to escape the burdens of discrimination. They’ve also offered a challenge to the American libertarian community: it’s truly anomalous, given the fascinating and moving history of the black American freedom struggle, and the fact that it so perfectly demonstrates much of the libertarian argument, that libertarians have themselves rarely given it a central role in their case for liberty.

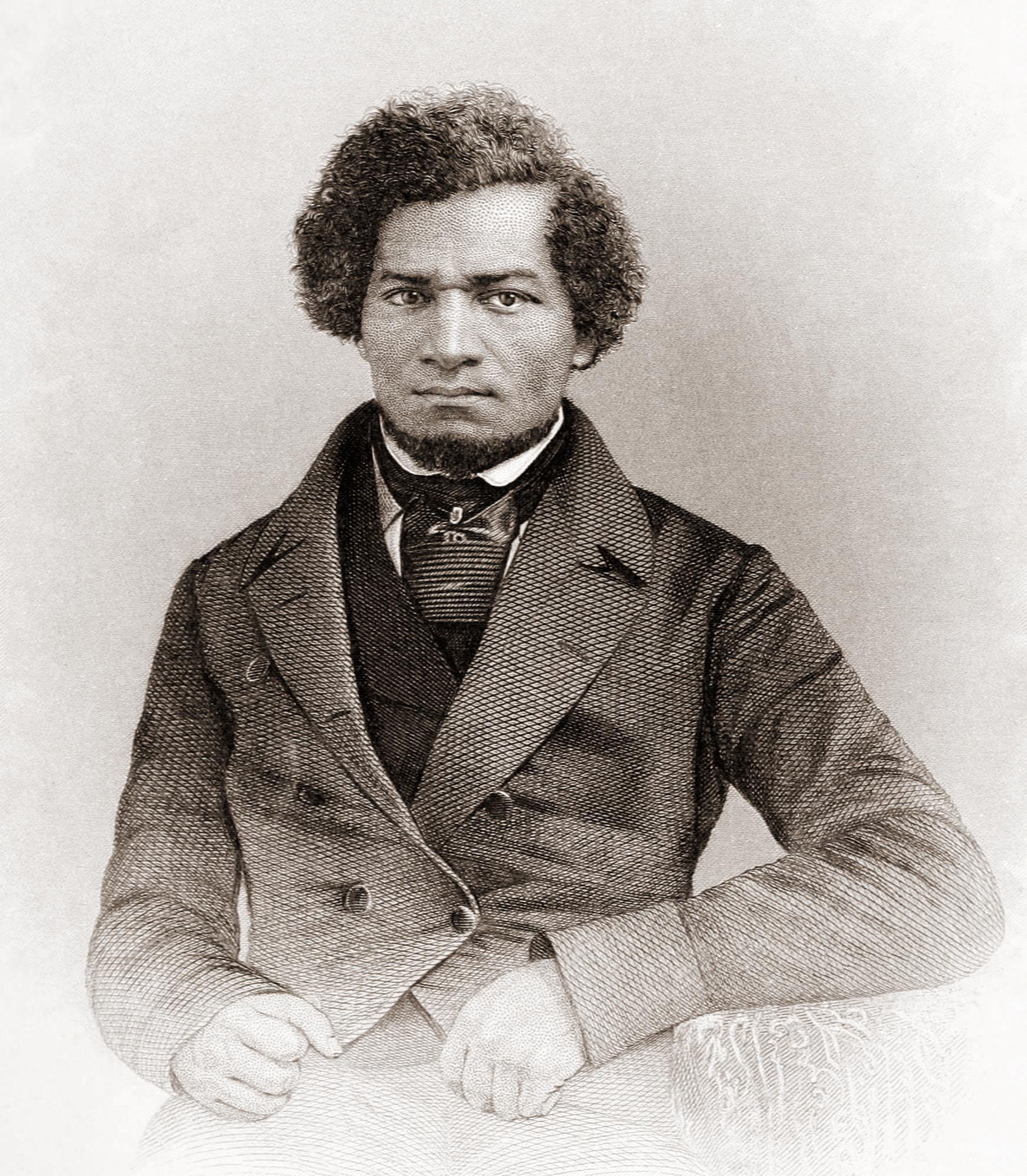

Despite prominent and honorable exceptions such as Thomas Sowell and Walter Williams—and, of course, the figures our essays have highlighted, such as Frederick Douglass and Zora Neale Hurston—few well-known champions of libertarianism have been black, and such leaders as Ayn Rand, Ludwig von Mises, and Murray Rothbard rarely devoted much attention to the specific challenges faced by black Americans during their lifetime. Worse—far worse—is the fact that in today’s world, libertarianism is often associated with outright racists, thanks largely to the political tomfoolery of the Libertarian Party’s so-called Mises Caucus. Given circumstances like these, it’s no wonder many black Americans are turned off by the very word “libertarian.”

As disappointing as the estrangement between blacks and classical liberalism is, it can only be remedied by first understanding its origin. And here the story largely begins with the famous clash between Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. DuBois—perhaps the most interesting political debate of the twentieth century, and one which is fundamental to any grasp of the distinctive political challenges black Americans confront today.

Washington, the famous leader of the Tuskegee Institute, was born into slavery in Virginia in 1856. Only after the Civil War did he get a chance to attend school. He fell in love with learning, and labored in coal mines to put himself through school, where he impressed his teachers enough that they chose him to lead Tuskegee—a position he held for three decades. After Frederick Douglass’s 1895 death, Washington—who, incidentally, published one of the first biographies of Douglass—was considered the grand old man’s successor as “leader of his race.”

But that same year, Washington’s philosophy regarding black resistance to oppression became controversial—and it remains so today, for reasons that are crucial to understand by anyone wishing to appreciate, let alone resolve, black America’s alienation from the libertarian world.

Washington thought black Americans should concentrate on “self-reliance”— learning trades, developing businesses, and climbing by their own efforts into a position of economic autonomy. That did not mean cutting themselves off from white America, but it did mean they should strive for economic stability, instead of devoting themselves to political and social agitation on the segregation issue. For one thing, Washington thought such activism was futile at that point—white Americans were simply too wealthy and powerful; only after a significantly large black middle class grew up, could blacks hope to end Jim Crow. But Washington also thought that if black Americans developed a culture of self-reliance, they would not have to depend on white America so much to begin with. If blacks built their own farms and factories, owned banks and insurance companies, became medical and legal professionals, whites would soon find themselves impelled to some kind of détente.

What’s more, it was simply good for a person’s character not to care what other people think of him. Washington liked to relate a story that Frederick Douglass told him of a time when Douglass was on a train, and was ordered to move to the Jim Crow car. When another passenger expressed regret that Douglass had been “degraded in this manner,” Douglass replied, “They cannot degrade Frederick Douglass.” Washington hoped all black Americans could someday earn sufficient financial independence to shrug off racism the same way.

In September 1895—only seven months after Douglass’s death—Washington spoke in Atlanta to a largely white audience, and summarized his views:

As we have proved our loyalty to you [whites] in the past, in nursing your children, watching by the sick-bed of your mothers and fathers, and often following them with tear-dimmed eyes to their graves, so in the future, in our humble way, we shall stand by you…interlacing our industrial, commercial, civil, and religious life with yours in a way that shall make the interests of both races one. In all things that are purely social we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress. There is no defense or security for any of us except in the highest intelligence and development of all…. The agitation of questions of social equality is the extremest folly…. Progress in the enjoyment of all the privileges that will come to us must be the result of severe and constant struggle rather than of artificial forcing. No race that has anything to contribute to the markets of the world is long in any degree ostracized. It is important and right that all privileges of the law be ours, but it is vastly more important that we be prepared for the exercise of these privileges. The opportunity to earn a dollar in a factory just now is worth infinitely more than the opportunity to spend a dollar in an opera-house. [Bolding mine]

The man who would become Washington’s nemesis, William Edward Burghardt Du Bois, was born to a well-heeled, educated family in Massachusetts in 1868. He became the first black man to earn a Harvard PhD, and his historical and sociological scholarship remain influential today. He started out as a Washington admirer, but became his sharpest critic a few years after the Atlanta speech, when he decided that the “self-reliance” philosophy was in many respects a form of victim-blaming. “[Washington’s] doctrine,” wrote Du Bois in 1903, “has tended to make the whites, North and South, shift the burden of the Negro problem to the Negro’s shoulders and stand aside as critical and rather pessimistic spectators.” The “self-reliance” philosophy gave “the distinct impression” that “the prime cause of the Negro’s failure to rise more quickly is his wrong education in the past,” and that “his future rise depends primarily on his own efforts”—when the brutal reality was that segregationists were responsible for obstructing every effort by blacks to attain educational, economic, or social success.

It's easy to caricature, but important to seriously weigh, the positions of both Washington and Du Bois. In reality, each argument had merit. To accept being segregated (like the fingers of a hand) as Washington suggested was surely like ashes in the mouths of those who had been wronged time and again by white supremacy. Yet on the other hand, the “agitation” Du Bois was advocating was unlikely to succeed—and certainly could not, without the financial support of the bourgeois class Washington was trying to build. Washington was right that “no race that has anything to contribute to the markets of the world is long in any degree ostracized”—but Du Bois was right that a time must come when black Americans laid down their tools and took up their picket signs, and that the time may as well be now.

Simply put, the Washington / Du Bois debate was a tragedy wrapped in a sort of yin-yang dilemma. And it left a legacy today by setting the stage for the political tensions among contemporary America’s black population. At the risk of the aforementioned caricature, one can loosely lump the “conservative” strain of black political thought—represented by figures such as Clarence Thomas or Glenn Loury—with Washington’s legacy, and the “liberal” strain—represented by Barack Obama or Kamala Harris—with Du Bois’s.

The problem for classical liberalism was that it became almost entirely associated with the Washingtonian wing—thanks largely to the work of Du Bois and his admirers, who after Washington’s death increasingly embraced the political left. In fact, Du Bois joined the Communist Party, renounced his American citizenship, celebrated Hitler during the Nazi-Soviet alliance, and published a revoltingly admiring obituary for Joseph Stalin in 1953. As Lucas Morel has noted, Zora Neale Hurston—an outspoken devotee of Washington’s, who knew and despised Du Bois—denounced the rise of communism among her Harlem Renaissance peers, and even came to view the Du Bois side of the black political spectrum as motivated by envy: she thought they were embarrassed at their own blackness. But she was the rare exception. From Langston Hughes to Richard Wright to Bayard Rustin, twentieth century black intellectuals were attracted to the Communist Party’s claim that racism is just a device used by elites to oppress the working class, and that overthrowing capitalism will also end racism.

That claim is absurdly false—and it turned out that Soviets were actually manipulating black intellectuals for their own advantage—but in the 1960s, it seemed to many that the Du Bois side of the debate was vindicated by the triumphs of the Civil Rights Era. (It appears more than merely symbolic that the old thinker died at the age of 95, only a day before Martin Luther King delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech.)

What’s more, Du Bois and his admirers persuaded many that the “self-reliance” argument amounted to a “do-nothing” attitude, just as leftist political thinkers have typically seen capitalism not as a spontaneous order but as an unplanned chaos. In their eyes, counseling the oppressed to patiently wait for markets to correct themselves—to focus on self-improvement in hopes of liberation “someday”—was both senseless and insensitive; their response was summarized in the title of the book King published on the 100th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation: Why We Can’t Wait.

By the time of King’s death, the Washingtonian philosophy of self-reliance was viewed by the most prominent black leaders not just as obsolete, but unrealistic—and that lack of realism appeared to be perfectly symbolized in the fight over the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which the nascent libertarian community viewed as a violation of private property rights.

A half century later, the relationship between black Americans and the libertarian world remains more or less at an impasse for precisely that reason. The question—to borrow the title of another of King’s books—is Where Do We Go From Here?

There’s no simple answer, but the first step is to keep in mind the lessons learned in the sixty years since King’s day. Those decades have witnessed the development of powerful intellectual tools—most notably public choice theory—that help explain why government intervention in markets might sometimes seem like a panacea, but over the long term actually entrench established power-players and can prove counterproductive when bureaucracies become “captured” by the very entities they’re supposed to regulate. The consequences of such capture are typically most severe on those who wield the least political influence—typically, members of minority groups.

Relatedly, classical liberals should always make clear that they aren’t champions of business, but of free markets—and these are not only different, but sometimes contradictory things. The libertarian economic ideal is one of dynamic and disruptive entrepreneurialism: a world in which businesses are kept on their toes by the constant threat of competition. The pro-business mindset, by contrast, is typically conformist and timid—and it was that Babbitt mentality, through a mix of cowardice and traditionalism, that enabled Jim Crow to fester for so long. The libertarian attitude isn’t “don’t rock the boat”—it’s “freedom now.” Unfortunately, their healthy skepticism toward central planning often misleads classical liberals into the pitfalls of the former attitude—what I call “The Romance of Gradualism.” That’s something libertarians should avoid.

Another important development is the spectacular vindication of the classical liberal critique of socialism. The Soviet Union’s collapse, and the examples of China and North Korea, have made it impossible to believe, as Du Bois did, that government planning “in the production of wealth and work” can build “a state whose object is the highest welfare of its people and not merely the profit of a part.” In fact, history has revealed that collectivist nations are at least as racist as freer countries are—and typically moreso.

In other words, in making the case for why black Americans should consider their arguments, non-white libertarians should focus on the future: on the question of how free markets, private property rights, freedom of speech, individualism and economic and social dynamism, all offer a better future going forward than do the antiquated arguments left over from the days of the Great Society.

Still, however, libertarians will have a hard time making the case for the future if they do not know and fairly confront the past. The history of race in this country is a complicated, often dismal one—but it’s also a story that features great heroism and beauty. The path by which black Americans have risen from the status of literal property to the ranks of fellow citizens, and even to the top leadership roles in our society, within the span of a century and a half, is an epic all Americans can celebrate and cherish. Libertarians most of all.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.