Liberty Matters

Jacobs, Internment, and Action

INTRODUCTION

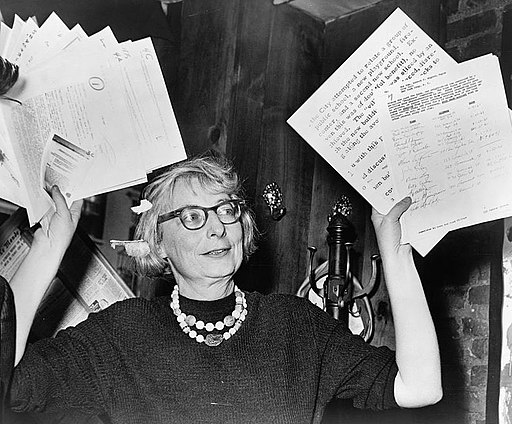

In my response to the essay by Rachel Ferguson and Marcus Witcher I will draw on what I have learned and thought about as a classical liberal working in economics and urbanism, the latter particularly through the lens of the urbanist Jane Jacobs. Indeed, I was asked to contribute to this conversation in part because of my familiarity with Jacobs’s writings. I will also, if I may, draw on some experiences close to home.

JANE JACOBS ON RACISM

Jane Jacobs has influenced classical liberals and progressives alike, and she can’t be easily classified ideologically. Indeed, she refused throughout her life to explicitly identify with any ideology and claimed not to have one. However, John Blundell lists her among the “ladies for liberty” (2011) and in my opinion that’s fair. In my recent book, I also try to point out the strong classical-liberal elements in her writings (Ikeda 2024: 379-380).

While most of her writings don’t directly treat the problem of racism, in her most famous book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities (Death and Life), she devotes a fair amount on the impact of urban planning on the neighborhoods of (in the nomenclature of the day) “Negroes” and “Colored People.” To some critics today that has not been enough, but one should consider that she wrote most of Death and Life in the late 1950s, a period when books about the socio-economics of cities were just beginning to deal explicitly with racial issues.

In the first part of Death and Life Jacobs discusses “red lining,” the practice by financial institutions of excluding certain neighborhoods from lending. Her discussion here is largely race neutral, and in fact focuses on predominantly low-income white neighborhoods such as Boston’s North End that were so designated and the way their residents coped by using local resources and their resourcefulness. Given the tendency of even fans of Jacobs to focus mainly on the first chapters of Death and Life, it’s possible that those accusing her of downplaying racial problems may have overlooked chapter 15 on “unslumming” (the North End may be seen as an example of this process), which brims with instances of heavy handed urban planning and “slum clearance,” with the aid of federal funding, damaging or destroying predominantly poor Black communities.

The discrimination which operates most drastically today is, of course, discrimination against Negroes. But it is an injustice with which all our major slum populations have had to contend to some degree (Jacobs 1961: 283).

But even earlier in the book than that, in chapter 6 on city neighborhoods, Jacobs explains why post-War housing projects in New York, Chicago, and elsewhere not only destroyed vital-but-poor Black neighborhoods but also how the projects that replaced them created the conditions – remote high-rise buildings with drab unkempt interiors and isolated public spaces – that discouraged the kinds of informal social contact that naturally fosters the basic safety and security that is the foundation of any successful community.

But when slum clearance enters an area…it does not merely rip out slatternly houses. It uproots the people. It tears out the churches. It destroys the local business man. It sends the neighborhood lawyer to new offices downtown and it mangles the tight skein of community friendships and group relationships beyond repair (Jacobs 1961: 137).

Today, “market urbanists,” who seek to find market-based solutions to urban problems such as homelessness and affordable housing, have taken up Jacobs’s work and point out the racist consequences, if not intent, of building codes and various forms of land-use zoning in the United States that has its roots in racial exclusion (Ikeda and Hamilton 2015).

As Ferguson and Witcher note, Ayn Rand rightly characterizes racism as “the lowest, most crudely primitive form of collectivism.” But another dangerous form of collectivism is “nationalism” – the belief that one should always place the interests of the country in which one is born above all else. And nothing fans the flames of nationalism more than war. In the 1940s, here and abroad nationalism merged frighteningly with racism.

WORLD WAR TWO AND JAPANESE-AMERICAN INTERNMENT

Then and now, war makes otherwise decent people apologists for the atrocities their governments commit. In the case of America during the Second World War, these included, to name but two, the imprisoning of tens of thousands of American citizens of Japanese ancestry merely because of their race, and the burning, crushing, and irradiating of tens of thousands of Japanese civilians in Hiroshima and Nagasaki because of their nationality.

The impact on my family during that time was far less severe but still deeply disruptive. My mother and father were second-generation Japanese Americans (JA). To escape Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s prison camps, my mother and her family fled California to the relative safety of Arizona. However, my father, a successful farmer in Arizona, was legally forbidden from entering the state capital to sell his produce, and as a leader in the JA community, he was hounded by the Federal Bureau of Investigations to “name names” when there were none. There is no better example of the perversion of the word liberal than to describe the president who ordered this to happen (via EO 9066) as “liberal.”

TRANSLATING RESPECT FOR INDIVIDUAL RIGHTS INTO CONSTRUCTIVE ACTION

As a “person of color” who was born and raised in the Southwest of mid-century America, when I attend events in the United States hosted by organizations for libertarians young and old I tend to note how many other People of Color (POC) are there among the regular participants. Over the 40-odd years I’ve been going to these gatherings I’m usually disappointed by the few I see. Has libertarian “colorblindness” indeed made us blind to people of color?

Ferguson and Witcher identify libertarian thinkers and doers throughout American history who have championed the cause of racial equality. In the twentieth century these include some who have supported civil rights for African Americans in the 1960s (e.g. removing “Jim Crow” laws and legal racial segregation) and in the 1980s redress for Japanese-American internment (though not monetary reparations). But their names (e.g. Murray Rothbard and Ayn Rand, as well as Karl Hess and Robert Lefevre) are not recognized as national leaders in these fights, and rightly so. If Ferguson and Witcher are right about the strong heritage of racial equality among earlier American libertarians, what has happened to that fervor in more recent times? And why is it that even today the day signifying the emancipation of Black slaves – Juneteenth – is mostly ignored by libertarians? Shouldn’t we be celebrating this holiday no less enthusiastically than the other American Independence Day?

Like Rose Wilder Lane (as the authors note), we also seem to be “late to the struggle,” the few exceptions notwithstanding, and at best follow rather than lead, often reluctantly. So, their claim that “the principled commitment to the individual rights of Americans translates into a passionate condemnation of all forms of collectivist oppression, whether racial or otherwise” sounds more like a wish than a statement of fact. How much has that commitment actually translated into taking action against all forms of racism and, like Adam Smith speaking up for the most vulnerable in our communities?

Ferguson and Witcher make an important and much-needed point, but will efforts such as theirs move the libertarian needle? I hope so. It did in a sense for me because, well, thanks to a few libertarians like them, for the past two years I’ve been celebrating Juneteenth. (Yes, I too am very late to the party.) That’s a very small step, of course, but one among many more that all libertarians need to take. As for the bigger picture, I am in wholehearted agreement with the title of their book (which I have not yet read): Black Liberation through the Marketplace. The advancement of minorities and the marginalized in society is demonstrably most effectively accomplished through free markets, free association, and radical tolerance (and criticism). These have worked miracles for human well-being across the board for at least the past 250 years, and, if given the chance, will do so for at least the next 250.

WORKS CITED

Blundell, John (2011). Ladies For Liberty: Women Who Made a Difference in American History. New York: Algora Publishing.

Ferguson, Rachel S. and Marcus M. Witcher (2022). Black Liberation Through the Marketplace: Hope, Heartbreak, and the Promise of America. Brentwood, TN: Emancipation Books.

Ikeda, Sanford (2024). A City Cannot Be a Work of Art: Learning Economics and Social Theory from Jane Jacobs. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ikeda, Sanford and Emily Hamilton (2015). “How land-use regulation undermines affordable housing,” Mercatus Center, George Mason University (November). https://www.mercatus.org/students/research/research-papers/how-land-use-regulation-undermines-affordable-housing Accessed 21 July 2024.

Jacobs, Jane (1961). The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Vintage.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.