Liberty Matters

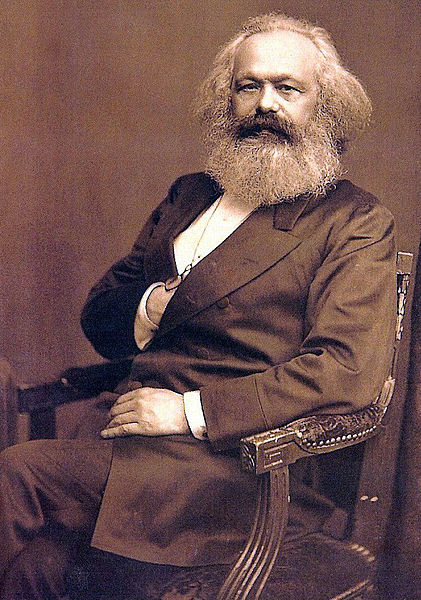

Duplicate of Virgil Storr, “Marx and the Morality of Capitalism” (October 2018)

Just as Virgil pointed out that our responses to him were more or less what he would have expected, so too is his rejoinder more or less what I expected. I want to use his rejoinder to say a few words about two topics that run through that rejoinder as well as Pete's commentary. The recurrence of both "aesthetics" and "empirics" in this conversation deserves some attention as we think about the relevance of Marx in the 21st century.

Just as Virgil pointed out that our responses to him were more or less what he would have expected, so too is his rejoinder more or less what I expected. I want to use his rejoinder to say a few words about two topics that run through that rejoinder as well as Pete's commentary. The recurrence of both "aesthetics" and "empirics" in this conversation deserves some attention as we think about the relevance of Marx in the 21st century.Before I do that, one quick word about Virgil's central banking analogy. I don't think that's an example of a liberal-standpoint problem for two reasons. First, even if a free-banking system is politically (nearly) impossible to achieve, that's not the same as logically or theoretically impossible to achieve. Whatever the merits of the "standpoint" criticism of Marx, the argument is that criticisms that depend on the existence of a world that is logically or theoretically impossible should not carry much, if any, force. The free-banking case is not subject to that claim because it has no logical or theoretical flaw even if it's not going to happen politically. Second and relevant to the role of empirics, we actually have examples of banking systems that operated without central banks and that aligned near perfectly with the institutions of a free-banking system. And we know that they worked well, even if the logic of politics eventually undermined them. We have no such positive example for Marxian socialism. If anything, as Pete's work on the early years of the Soviet Union shows, we have an empirical example of its failure. (Boettke 1990) Virgil's response to the gravity analogy is more effective, I think, than is the central-banking analogy.

What I want to say about the claim that Marx's critiques are ultimately, in light of the socialist-calculation debate, aesthetic is that this should serve as a lesson for critics of Marx and defenders of the market. There are two ways to respond to such criticisms. First, we need to respond at the aesthetic level. Second, we need to respond at the empirical level.

Aesthetically, what is most important is that liberals create a positive aesthetic of the market. I think the first part of my commentary that discusses Mises's Law of Association as a vision of peaceful social coordination is a start toward that aesthetic. One can view Leonard Read's "I, Pencil" as another example, particularly the film version of it produced by the Competitive Enterprise Institute. I've also written ("When Libertarians Cry," 2015) about the aesthetic power of Hans Rosling's TED talk on "The Magic Washing Machine." These are examples of how the market's promotion of peace, progress, social cooperation, and individual development can be portrayed in a counter-aesthetic to Marx. One can imagine other ways in which an aesthetic defense of the market might be mounted, focusing on how markets promote social cooperation and peaceful interaction. It is incumbent upon liberals, in the face of Marxian criticisms, to avoid speaking solely of "efficiency" and the like and to focus instead on the ways in which markets are beautiful and creative, how they enable us to self-actualize.

As Virgil notes, there is also room for an empirical response to Marx. Marxists have made a number of empirical claims about what markets do to humans, particularly the poor. Is it empirically true that the working class has been "immiserated" by capitalism? Is it even empirically valid to speak of class divisions in terms of ownership of the means of production where so many in the working class own stock either directly or, more often, indirectly through retirement plans? And what does the advent of Uber, Lyft, and Airbnb mean for Marxian class theory when more and more individuals own their own means of production and work, essentially, for themselves? Has capitalism become less competitive and more monopolistic? Are consumers in general worse off? Is inequality substantially worse than in the past?

All of these are important empirical questions whose answers can serve as responses to Marxian criticisms even if we dismiss the standpoint problem. Making those empirical arguments is something I've tried to do in my own work, most notably in a 2015 article in Social Philosophy and Policy, but also in a variety of blog posts and public lectures. Deirdre McCloskey's Bourgeois Virtues trilogy (2006; 2010; 2016) is a contribution to this effort as well. And "empirics" here need not be limited to statistical data. The narratives we can tell about the ways in which real people have made use of the market and the emergent order of civil society to solve problems and improve their lives are just as important.

Responding to Marx will require both a liberal aesthetic vision and rigorous liberal scholarship about the empirical and historical accomplishments of markets. Those two projects will also be deeply intertwined. Thanks to Mises and Hayek and others, liberalism may have won the day theoretically, but a fully effective reply to Marxian criticisms of capitalism will require aesthetic and empirical responses as well.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.