Liberty Matters

Beyond War: The Economic Case for Nonviolent Revolution

These essays have discussed the costs of conflict on women in fine detail, but it might be helpful to examine this from a broader view. Wars and violent revolutions arise from fundamental human aspirations: expelling foreign occupations, removing dictatorships, achieving self-determination, and pursuing transformative social change. These motivations represent legitimate grievances demanding resolution. Yet, conventional wisdom presents a false binary—that societies must choose between violent resistance and passive submission to oppression.

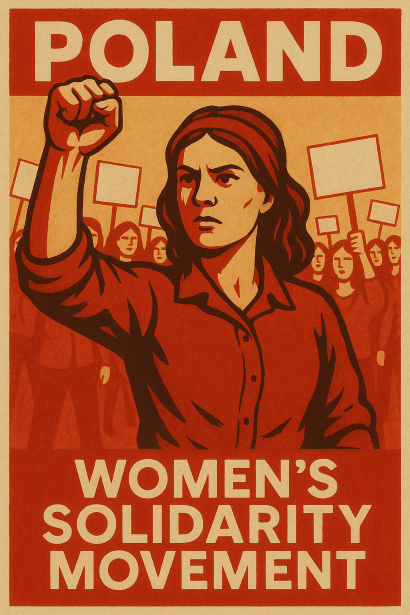

This dichotomy persists despite overwhelming historical evidence of a third path. The Solidarity movement expelled Soviet influence from Poland. The People Power Revolution removed Ferdinand Marcos's dictatorship in the Philippines. India achieved independence from British rule. South Africa dismantled apartheid, primarily through sustained nonviolent pressure. Regime change, expelling foreign armies, and major social change (like anti-apartheid) are the justifications for most modern wars, and these motivations are a requirement to enter the dataset on nonviolent revolutions that I use in my research. Economics, at its core, examines the costs and benefits of alternatives given constraints. When we apply this framework rigorously to conflict resolution, the superiority of nonviolent action becomes clear. That is why a former Lithuanian defense minister said, “I would rather have this book [Civilian-Based Defense] than the nuclear bomb.”

Why does the myth of inevitable violence persist? Government institutions systematically fail at entrepreneurial discovery, including recognizing alternatives to violence. This failure reflects deeper issues about how lasting change actually occurs.

Informal institutions—the cultural norms and practices that emerge bottom-up—often matter more than formal rules imposed through force. War may change laws on paper, but lasting institutional change requires cultural shifts that cannot be imposed through violence. The Kirznerian entrepreneur we need isn't the military commander but the grassroots organizer who recognizes opportunities for peaceful transformation.

The war in Afghanistan was sold partly as advancing women's rights, and briefly, it appeared to succeed. But economics teaches us that alternatives matter. Genuine expansions in women's property rights historically emerged through peaceful interjurisdictional competition rather than violent conflict.

My research demonstrates that we should expect nonviolent revolutions to produce greater and more durable gains in women's de facto property rights compared to violent conflicts. These de facto rights prove more important than de jure rights for long-term development. While external force may temporarily impose a regime that helps women, nonviolent action wins in the long run.

Economic freedom drives growth. Cultural values emphasizing individual autonomy advance women's economic rights. John Stuart Mill taught us that the subjection of women often includes limiting their ability to participate in markets and their autonomy. Domestic abusers know this is effective. While the shock of war may generate some temporary, unintended benefits in the labor market, we must explore more sustainable bottom-up solutions that facilitate what Elise Boulding calls “cultures of peace.”

How do nonviolent movements succeed where violence fails? Voluntary associations—from women's clubs to modern NGOs—provide public goods without violence. International trade creates positive-sum alternatives to zero-sum conflict. These mechanisms preserve economic capacity while building new institutions.

How can women challenge the warfare state? Whistleblowers expose government abuses precisely because normal channels fail. Women can protest. For example, Fanny Garrison Villard and Eva Macnaghten, members of the Women’s Peace Society and the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom in the 1920s, were hugely influential in promoting free trade and peace.

The entrepreneurial pathways to peacemaking show how bottom-up discovery processes identify and implement solutions that centralized violence cannot achieve. Look at Homegirl Cafe, which employs women who have experienced violence or are formerly incarcerated. This isn't merely theoretical—it's demonstrated repeatedly in successful nonviolent movements worldwide.

The choice between violence and submission is false. The real choice is between war's documented devastation and the transformative potential of organized nonviolent resistance. Applied to conflict, economic logic is inescapable: the case for peace represents not just a moral ideal but an economic imperative.

Current resource allocation reveals our collective failure to internalize this lesson. Military expenditures exceed these nonviolent methods. This misallocation persists because policymakers fail to recognize that peaceful preparation for peace offers more than violent preparation for war. Defense planning faces knowledge problems. Society needs Kirznerian entrepreneurs who identify these opportunities for peace and make their visions a reality.

Our task as scholars is to ensure this alternative remains visible, viable, and victorious. This isn't merely an academic exercise but an urgent contribution to human flourishing. The evidence demands we apply the lesson that bottom-up solutions consistently outperform top-down interventions to humanity's greatest challenge: transcending violence itself.

When economists ask what makes their discipline uniquely valuable, it's the consistent application of economic logic to real-world phenomena. That logic, properly applied to conflict resolution, yields an inescapable conclusion: nonviolent action dominates violent alternatives on every meaningful metric—economic, institutional, and human.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.