Liberty Matters

How Peaceful Revolutions Transform Women’s Lives

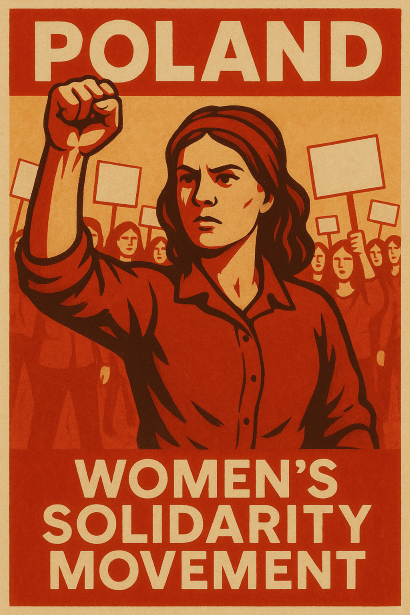

When Anna Walentynowicz was dismissed from her job at the Lenin Shipyard in Gdańsk, Poland, in 1980, she probably did not imagine she would spark a movement that would transform women's economic rights across an entire nation. Her spark grew into the Solidarity Movement, an unarmed revolution that reshaped how Polish women could own property, participate in the economy, and shape their futures.

Data from dozens of countries over the past century shows that nonviolent revolutions expand women's actual, day-to-day property rights even when the legal code has not caught up. In the years following a peaceful revolution, women's ability to own, inherit, and control property expanded dramatically. However, when we examine the formal laws on the books, we often see little immediate change.

To understand this phenomenon, we need to clarify what we mean by different types of rights and empowerment. When I talk about "de facto" property rights, I mean women's actual, observed ability to buy land, open businesses, inherit from their families, and make economic decisions, regardless of what the law says. For this, I use property rights for women from the Varieties of Democracy Index (V-Dem). These are the rights that matter in daily life: Can a woman walk into a bank and get a loan? Can she register a business in her own name? Will her community respect her ownership of inherited land?

In contrast, "de jure" rights refer to what is written in the legal code, the formal laws that technically govern property ownership. These might guarantee equality on paper but mean little if social norms, bureaucratic practices, or informal institutions prevent women from exercising these rights. The Fraser Institute's Economic Freedom of the World Index (EFW) provides this data.

I have also explored the effects of nonviolent regime change on three other variables from the V-Dem: civil liberties, civil society participation, and political empowerment. Civil liberties refers to women's freedom to move, associate, and express themselves without restriction. After nonviolent revolutions, women gain greater freedom to travel for work, attend meetings, and voice their opinions. These are essential preconditions for economic participation. Civil society participation measures women's involvement in organizations outside of government, labor unions, community groups, and business associations. It increases immediately after a nonviolent revolution, and these civil society institutions are critical for sustained advocacy of female rights. Political empowerment measures women's ability to influence decisions that affect their lives, not just through voting but through activism, organizing, and collective action. This grassroots political power often proves more effective than formal representation in changing economic realities.

Let us see how this worked in the example of the Polish Solidarity Movement. When the movement began in 1980, women made up a significant portion of the ten million members who joined. Women like Alina Pienkowska co-founded strike committees, negotiated with authorities, and became signatories to the historic Gdańsk Agreement that legitimized Solidarity.

These women did not wait for laws to change. Within Solidarity, they established specialized departments to advocate for female workers, securing maternity benefits, childcare access, and workplace protections through collective bargaining rather than legislation. When the government imposed martial law in 1981, women's informal networks kept the movement alive, facilitating communication between imprisoned leaders and maintaining the resistance through underground channels.

Before 1989, under Communist rule, the Polish state severely restricted private property rights. But after Solidarity's peaceful revolution succeeded, the score for women's property rights in V-Dem jumped to perfect, meaning virtually all women could own, inherit, and control property. This score does not mean that property rights are strictly protected like in the EFW, but rather that property rights are equally granted in legal and social settings. This transformation happened primarily through changing social practices, business norms, and institutional behaviors rather than immediate legal reforms.

Women used underground media networks to demand new laws and to show that both women and men privately supported women's economic participation far more than the official Communist narrative suggested. When these preferences became public knowledge through peaceful mass action, social change followed rapidly.

The success of nonviolent movements in advancing women's economic rights stems from several interconnected mechanisms. First, nonviolent movements require broad participation to succeed. This means women must be included as equal partners from the beginning. Women are systematically excluded from most military operations, and this discrimination limits the available number of dissidents within a country. This critical mass of female participation means women's concerns cannot be ignored when the new order is established.

Second, the skills and networks built during nonviolent resistance translate directly into economic empowerment. Organizing a boycott requires the same logistical capabilities as running a business cooperative. Leading a strike committee develops the same leadership skills needed to manage an enterprise. The social capital, trust, reciprocity, and mutual support forged during peaceful protests become the foundation for women's business networks and economic collaboration after the revolution.

Third, nonviolent movements must maintain moral legitimacy, which requires consistency between means and ends. A movement claiming to fight for freedom and dignity while excluding half the population loses credibility. This pressure for internal consistency often forces nonviolent movements to model the gender equality they seek, creating new norms through practice rather than proclamation.

Formal legal reforms often come years or even decades after women's actual economic practices have already changed. The evidence suggests that when women gain real economic power through changed social norms and practices, they eventually accumulate enough influence to formalize these gains in law.

This sequence is intuitive. Changing laws requires access to formal political power, seats in parliament, influence over judicial appointments, and connections to legislative committees. But changing social practices requires only collective action and community agreement. Women participating in nonviolent movements build social power, which they can use to secure formal, legal power.

In the Polish example, the immediate post-revolution period saw women exercising property rights through practice, starting businesses, inheriting land, accessing credit, even as the formal legal code lagged. Only gradually, as women's economic participation became normalized and their political influence grew, did comprehensive legal reforms follow. The trend is present consistently. Nonviolent mobilization creates space for women's economic participation, which generates resources and networks that women use to demand formal rights, which eventually become codified in law.

These historical movements illustrate potential paths for female rights. International development organizations often focus on changing laws, pushing countries to reform property codes, mandate equal inheritance, or guarantee women's business rights. While these legal reforms matter, research suggests informal institutions rule.The more effective path runs through grassroots mobilization and social change.

When women participate in peaceful mass movements, they do not just change governments. They transform the everyday assumptions, practices, and norms that determine economic opportunity. A woman who has stood shoulder-to-shoulder with men in protests finds it easier to stand as their equal in business negotiations. Communities that have seen women lead strike committees find it natural for women to lead companies.

Legal reform is important but sustainable legal change requires a foundation of shifted social norms and women's actual economic participation. Laws imposed from above without this foundation often remain impressive on paper but meaningless in practice. Laws that formalize existing social changes tend to stick because they are backed by constituencies with real power to enforce them.

Women around the world continue to use nonviolent resistance to claim their economic rights. From Iran's "Woman, Life, Freedom" movement to Sudan's revolution led significantly by women, we see the same patterns emerging. These movements do not begin with demands for property law reform. They start with demands for dignity, freedom, and recognition as whole human beings. But in pursuing these goals through peaceful mass action, they create the conditions for lasting economic transformation.

Supporting women's economic rights means supporting their ability to organize, protest, and peacefully resist. It means protecting civil society organizations where women build collective power. It means understanding that messy, bottom-up social change often proves more durable than neat, top-down legal reform.

For women living under systems that deny their economic rights, this research offers hope and strategies. The path to economic freedom does not require waiting for enlightened leaders to grant new laws. It runs through collective action, peaceful resistance, and the patient work of changing minds and norms one community at a time. The peaceful revolutions that succeed in transforming women's economic lives are not just changing rules. They are changing culture. Cultural change, once achieved, proves remarkably difficult to reverse.

The women of Poland's Solidarity Movement understood this. They did not wait for permission to claim their economic rights. They organized, resisted, and created new realities through collective action. In doing so, they demonstrated that peaceful revolutions succeed in advancing women's economic freedom not by imposing new rules from above, but by empowering women to write new rules from below. Moreover, those rules, written through struggle and solidarity, have a way of lasting.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.