Liberty Matters

The Revolutionary Paradox: Building on Compromised Foundations

I am grateful to Abigail Hall, Claudia Williamson Kramer, and Jayme Lemke for their explorations of war's relationship with women's economic empowerment. Their contributions illuminate different facets of a fundamental tension that my research on nonviolent revolutions has also uncovered: progress toward liberal institutions rarely follows the clean trajectories our theories might predict.

Consider a striking historical irony that encapsulates this tension. Mississippi became the first U.S. state to grant property rights to women—not from enlightened principles of equality, but from a desire to preserve slavery. Judges extended these rights primarily so widowed women could maintain ownership of enslaved people after their husbands died. The alternative—hundreds of enslaved individuals potentially gaining freedom through the legal technicality of a slaveholder's death—was unfathomable to the antebellum court. It would take a civil war to free these enslaved men and women from these widows. This perverse origin story of women's property rights reveals an uncomfortable truth about liberal progress. It often emerges from morally compromised foundations, yet can transcend those origins to serve higher purposes.

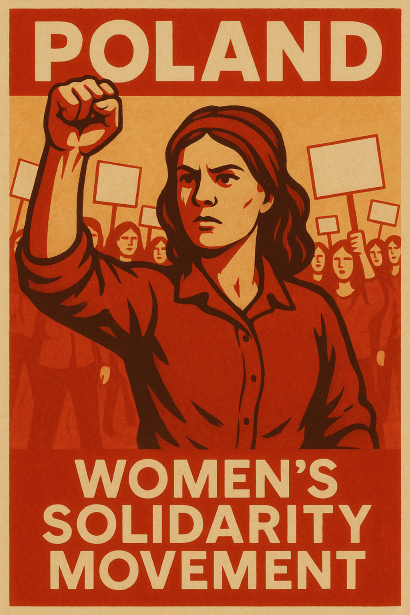

Hall's call for alternative methodological approaches when studying war's gendered impacts resonates with researchers studying transition economies. Her observation that good data on military casualties and expenditures remains insufficient for statistical analysis mirrors my experience studying nonviolent revolutions. When examining Poland's Solidarity movement, the quantitative finding that women's property rights jumped on Varieties of Democracy Index (V-Dem)'s scale tells only part of the story. The fuller narrative—of Anna Walentynowicz's dismissal sparking mass strikes, of women like Alina Pienkowska co-founding strike committees, of female activists maintaining underground networks during martial law—reveals mechanisms that regression coefficients cannot capture. These analytical narratives, as Hall suggests, become essential for understanding how women are drivers of institutional change.

Kramer's provocative application of price theory to war's impact on women deserves serious engagement, particularly her insight that war's devastation (e.g., loss of male labor, economic collapse, and fiscal pressures) lowers the price of granting women legal economic rights. This framework helps explain patterns in my own data: nonviolent revolutions consistently improve women's de facto property rights. At the same time, formal legal changes in the Gender Disparity Index show more modest effects. Like Saudi Arabia's Women, Business and the Law (WBL) index leap during the Yemen conflict that Williamson highlights, Poland's transformation emerged from pragmatic necessity as much as principled commitment. The revolutionary disruption made excluding women from full market participation too costly to maintain.

Yet this economic logic alone cannot explain the differential impacts I observe between violent and nonviolent revolutions. Here, Lemke's emphasis on power dynamics proves illuminating. Her distinction between "power over" and "power with" helps explain why nonviolent revolutions show more substantial positive effects across a variety of outputs than violent conflicts. As Lemke argues, militarization reinforces hierarchical command structures, while the participatory nature of nonviolent resistance builds horizontal networks of collaboration. There is some evidence that war can build civic participation, and research by the same author says that out-group discrimination increases. This point is important because while Hall notes that women have been valuable in combat roles, the vast majority of countries exclude women from participation.

The tensions between these perspectives become productive when we recognize instances where new institutions can arise from conflict like Elinor Ostrom identified. Kramer sees these moments in war's economic devastation, Hall in the broader disruptions conflict creates, and Lemke warns of their limitations when achieved through violence. My research suggests nonviolent revolutions create particularly favorable opportunity structures because they combine disruption with broad participation, necessity with legitimacy.

Hall's emphasis on understudied costs reminds us that our accounting remains incomplete. We know little about how wartime sexual violence affects long-term labor market outcomes, or how refugee displacement impacts gender roles. Kramer’s finding that post-conflict gains often depend on external pressure raises questions about sustainability—are World Bank-induced reforms merely autocrats striving to show gender equality with no substantive change, or can they create precedents that represent or foster true equality before the law? These questions remain unanswered for unarmed revolutions as well. The interaction between de jure and de facto rules in times of transition and conflict remains a fruitful area of study.

As I find across multiple countries, changing social practices through mass mobilization often precedes and enables formal legal change. The Mississippi example haunts this narrative: formal rights granted for the worst reasons can still create precedents that future generations repurpose for liberation. Today's property rights for women stand independent of their slaveholding genesis. Similarly, the pragmatic concessions Kramer documents in wartime may outlive their strategic origins if women can consolidate and expand them through collective action.

Lemke's skepticism about war's liberating potential extends implicitly to revolution as well. The path is not linear—Poland's recent restrictions on reproductive rights remind us that progress can reverse. Revolutions and wars, whether nonviolent or violent, conflict with liberalism's focus on stability and marginal improvements. I find, also, that GDP per capita decreases.

What unites our perspectives is recognition that women's economic empowerment rarely emerges from pristine moral victories. Instead, it advances through accumulating precedents, shifting norms, and expanding capabilities—even when these emerge from questionable sources. As Deirdre McCloskey argues, ideas—not perfect institutions—created the Great Enrichment. The women of Solidarity were given the brutality of socialism and transformed their society through collective action.

Perhaps this is liberalism's essential genius: its ability to grow from compromised soil toward higher ideals. The Mississippi judges who granted women property rights to preserve slavery could not have imagined that those same rights would one day enable black women's economic independence. The Communist authorities who negotiated with Solidarity could not have foreseen how women's resistance networks would reshape Polish society. Even we, studying these transitions, cannot fully predict how today's imperfect advances will serve tomorrow's liberation. What we can do is document, analyze, and learn from these complex processes. We can recognize that the path to women's economic empowerment—like the path to liberalism itself—winds through morally ambiguous terrain toward destinations we can only partially glimpse.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.