Liberty Matters

South Royalton Mattered but It’s Important Not to Isolate

Introduction

Because my original essay was a response to Richard Ebeling’s excellent essay, I’ll focus here on responding mainly to Mario Rizzo and Geoffrey Lea.

South Royalton Mattered

Both Mario and Geoffrey (explicitly) and Richard (implicitly) make the point that institutions matter. In particular, the South Royalton conference mattered. You can have some great ideas, but they might not go very far without institutions backing you up. Institutions provide two important inputs.

The first is resources. As I mentioned in my essay, someone (the Institute for Humane Studies) was offering to pay all my expenses to go to an interesting conference. Given my resources at the time, I almost certainly wouldn’t have gone if I had had to pay my own way.

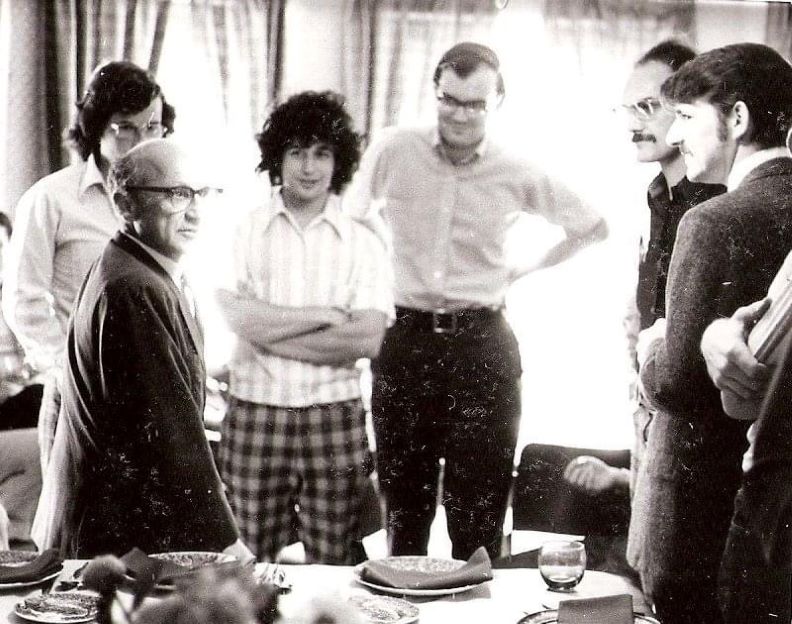

The second important input is contacts. Before I went to the South Royalton conference, I had met none of the other students who went there, other than my friend Harry Watson, with whom I went, and Jerry O’Driscoll, a fellow UCLA student who had mentored me somewhat during my first year at UCLA. Many of those students became friends and even those who didn’t became friendly acquaintances with whom I have kept in touch for half a century. When I run into Randy Holcombe at conferences, for example, he never fails to remind me that we first met at South Royalton and then usually adds, “Who knew when we went there that it would be that big a deal?” Who knew, indeed?

As far as faculty go, I had met Murray Rothbard once but had never met Israel Kirzner or Ludwig Lachmann. In my case, meeting them didn’t have a large direct impact on my career or my scholarly or popular work, but it probably helped me feel comfortable dealing with older economists who were accomplished.

I told the story, as did Richard and Mario, of Milton Friedman saying at the South Royalton conference that there was no such thing as Austrian economics but only good economics and bad economics. There is one important way in which Friedman’s comment mattered, even if it was not the way he intended. Far from discouraging the young attendees who heard him, his comment (at least in my view) amounted to his throwing down the gauntlet and challenging them to do good work. Many of them did, and much of it was in the Austrian tradition. Oh, and it was, by and large, good economics.

The Remnant

I’m glad that Geoffrey Lea expressed his misgivings about Richard Ebeling’s discussion of “the Remnant.” Even though I had read Richard’s essay carefully twice, I failed to comment on that part of his essay. But Geoffrey’s comment reminds me that I do have my own misgivings.

I shouldn’t blame Richard too much. I had misgivings in the 1970s, when I first read about Albert Jay Nock’s concept of the Remnant. As Nock himself admits in his famous 1936 essay, neither the “Remnant” nor the “masses” can be defined by class or station. Someone could be a bona fide member of the elite and still be a member of the masses; similarly, one could come from a humble background and be part of the Remnant. So even if one stuck to writing only for the Remnant, that would not mean that he or she should focus on a particular well-defined audience.

When he gets to his actual argument, Nock is essentially saying that we should not water down or compromise our thinking to appeal to the masses. I agree with that. Even if Nock didn’t intend it, though, thinking that one is producing ideas for the Remnant could lead one not to reach out to others. It could easily lead someone to isolate himself from all but those who already agree with him, whether they be fellow scholars or what might seem to be members of the “masses.” Fortunately, many members of the Austrian school have engaged in valuable outreach to people who might be mistaken for the “masses,” without compromising or watering down. In my view, Murray Rothbard is a case in point.

I do remember, though, the case of one prominent Austrian scholar who refused to reach out to a scholar who was not a member of the Austrian school. That Austrian scholar was Israel Kirzner. This might sound surprising, given my genuine praise of Kirzner in my first essay. But I distinctly remember a story he told the audience at either the South Royalton conference of 1974 or the Hartford conference of 1975.

Kirzner told of his excitement when hearing that Sir John Hicks, who had earlier won the Nobel Prize in economics, was writing an explicitly Austrian book. The 1973 book was titled Capital and Time: A Neo-Austrian Theory. Kirzner told of excitedly attending a session of the American Economic Association meetings in New York in 1973 at which Hicks was to present his “neo-Austrian” ideas. Kirzner said that after listening to Hicks present for a few minutes, he concluded that Hicks did not understand Austrian economics and he, Kirzner, got up and walked out before the session was over. When I heard Kirzner say that, I thought, “What a wasted opportunity!” It’s true that Hicks was not an Austrian. But a good-willed prominent economist, Hicks, who thinks he is doing Austrian economics is probably worth talking to. And who better to try to steer him in the right direction than the clear-thinking and normally patient Israel Kirzner.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.