Liberty Matters

The Unintended Consequences of Milton Friedman

Geoffrey Lea says that “as the ripples work further from the impulse, those ripples diminish in magnitude.” Taken literally, this is no doubt true. But there are some processes that amplify over time. I will argue that Milton Friedman’s little speech at the South Royalton dinner in 1974 is a case where the, at first, mere ripple was somehow magnified over time. To be sure, it was not the speech itself, but the fundamental idea in it that has worked to the disadvantage of a cause he cared deeply about: liberalism.

David Henderson gives the context of Freidman’s comments at that dinner. He had indeed been invited and was encouraged to say something. But when he said that there is no such thing as Austrian economics but only good and bad economics, he was making a profound point. We all knew that his conception of good economics was that it must be scientific in the sense of fundamentally mathematical in its analysis, consisting of testable propositions, and using up-to-date methods of empirical research. And this was the only acceptable method.

Why was Friedman so concerned about being scientific? He wanted to demonstrate that liberal ideas about the efficacy of free markets and the importance of general rules over government discretion could have a scientific basis. If there were to be a postwar revival of liberalism, it could not be on the terms of the pre-war liberals, especially the Austrians, who seemed so old-fashioned in their methods of analysis. They seemed to him to be dogmatic, ideological, and averse to the current trend of economic thinking. It is clear that he and others of the new Chicago school (yes, there was a Chicago school – everyone knew it – even though there was no Austrian school!) did not take seriously the anti-scientistic cautions of Frank Knight who had died in 1972.

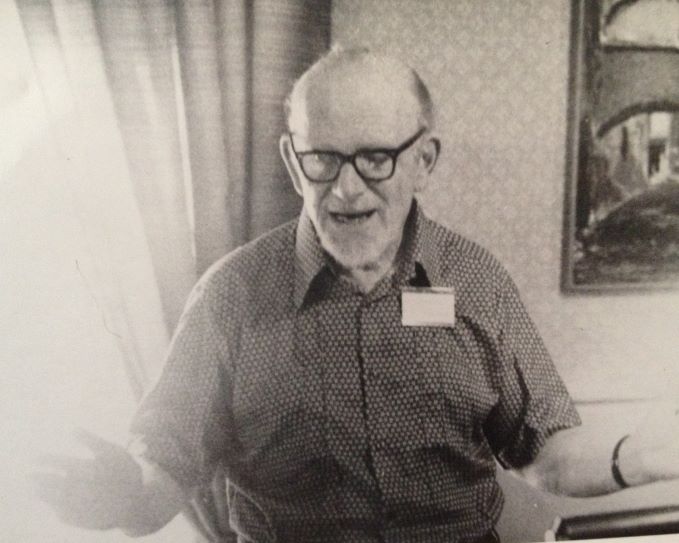

At South Royalton Murray Rothbard was quite angry and he had every right to be. I think those who invited Friedman thought he would be pleased about an Austrian revival. After all, it could be yet another route to re-establishing liberalism. But they should have known better based on Friedman’s writings and participation in Mont Pèlerin discussions.

Friedman’s point exemplified the general attitude held by his Chicago School – as well as most of the economics profession. As the decades rolled on, economic theory became increasingly more abstract and mathematical. Empirical methods developed by leaps and bounds. Experimental methods were introduced. Fields became ever more specialized and isolated from each other. The narrowness of neoclassical rationality was questioned. Some of this was to be expected and some even welcomed. But there was a major problem: The thrust to specialize and to be as “scientific” as possible meant that economists had no time to consider the broader social implications of their work. And, because entry into the economics profession involves self-selection, many young economists had no interest in such issues. A perfect example was an economics faculty meeting at New York University during the 1990s in which William Baumol, who had himself made contributions to the history of economic thought in earlier days, argued that the history of economic thought requirement for Ph.D. students should be abolished because the opportunity cost of studying broader issues was now too high in view of increasing technical nature of the discipline. The requirement was abolished over the objections of Israel Kirzner and Wassily Leontief. A classic case of crowding-out.

Of course, Milton Friedman could have had no idea that things would develop in this way. He could have no idea that the view of economics – which he shared with the mainstream of economists – would evolve into an exaggerated form and obsession. In part, he did not know this because Chicago had always been far more moderate in its formalism than was economics at Harvard, Yale, or MIT. Chicago economics always kept a close relationship with the real world and employed intuitively-plausible theories. They were Marshallians – you could burn the mathematics and you still had something. Economics was an engine for the discovery of concrete truth.

Crowding-out meant that economists, at the highest level, were increasingly ill-educated beyond narrower and narrower technical concerns. Education for economists today has no room for the study of political theory, the history of economic thought, heterodox economic ideas, even economic history and economic institutions. The idea of discovering the scientific basis of liberalism makes no sense at the “elite” (aka fancy-school) level of the economics profession. Nevertheless, many economists still opine on political matters but without any of the background to do so.

Who continues to pursue the substantive relationship between economics, philosophy and the other social sciences? Clearly, the Austrians have been prominent in all this. Others, beyond the elite mainstream, are involved too – witness the surge in interest in Philosophy, Politics and Economics (PPE) programs.

Friedman’s error was to put down the distinctively Austrian perspective, thinking that his view of science was the only one acceptable and not recognizing the dangers of scientism. Ironically, and without his intent or responsibility, the mainstream profession of economics today has crowded-out the informed concern with broad political and social issues. The scientism in Friedman’s science has overwhelmed the liberal framework he hoped economics could contribute to building.

But not among the Austrians.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.