Liberty Matters

A Vagabond Remnant

Richard Ebeling, in his usual fashion, has given a first-rate recounting of both the circumstances surrounding and the legacy of the 1974 South Royalton Conference. His essay, however, does not dwell on the conference itself—the talks given, the discussions and disagreements, the social aspects—but rather on the lasting significance of that week and its ripples through late twentieth and early twenty-first century economics. Anyone interested in the history of Austrian economics, either in America or globally, would benefit from a careful reading of Richard’s recollections and evaluations. His essay is broad and thorough; his mastery of the historical context and the dizzying growth of the subsequent literature are on full display.

By the end of the essay, however, I found myself disturbed by a nagging feeling of unease. I located the source of this unease in Richard’s reference to “the remnant,” and what I think it has to do with the state of Austrian economics today. Before turning to this unease, I offer an interpretation of why the South Royalton Conference was so successful in contributing to the success of Austrian economics in the intervening fifty years.

Richard is undoubtedly correct that South Royalton marks a “rebirth” of Austrian economics, especially in the two to three decades following the conference. Significant events have a half-life of their own that naturally diminishes their influence over time. So it seems it would have to be with something like South Royalton; it is no doubt life-changing for those in attendance, and a point of inspiration for others who are proximate to attendees, but as the ripples work further from the impulse, they diminish. The beginning of the Austrian renaissance lies in South Royalton because that conference and the broader context in which it took place planted the seeds for the success of Austrian economics both as a scientific research program and as an intellectual movement.

Peter Boettke has put forward a formula for thriving research programs in academia. He says, “The advancement of a scientific research program requires at least three things: ideas, funding, and academic positions.” (Boettke 2012, 34) Austrian economics, in this respect, became and remains a progressive scientific research program in part due to South Royalton. At present, it seems likely that the set of ideas encompassing Austrian economics is more successful as a research program (in terms of funding and academic positions) than it has ever been—or at the very least since the 1930s or 40s. Richard’s delightful and thorough recounting of recent scholarship across the various strands of modern Austrian economics gives proof to this assessment.

Along the lines of Boettke’s “ideas, funding, and academic positions” for a scientific research program, the success or advancement of an intellectual movement requires at least three things: ideas, individuals, and institutions. (I am here using the term institution to mean an organization, not a rule of the game and its enforcement.) Ideas are a necessary part of success for both scientific research programs and for intellectual movements. Richard correctly notes that for many of this “first generation,” a return to the texts was necessary and beneficial. The ideas of the “older,” European Austrian School, expressed in the writing of Karl Menger, Eugen Böhm-Bawkerk, Friedrich von Wieser, Ludwig von Mises, F. A. Hayek, and others, have inspired generations of students, scholars, researchers, pundits, and activists. Austrian economics has never suffered from a lack of ideas; what made South Royalton so important for the future of Austrian economics was that it successfully combined individuals and institutions.

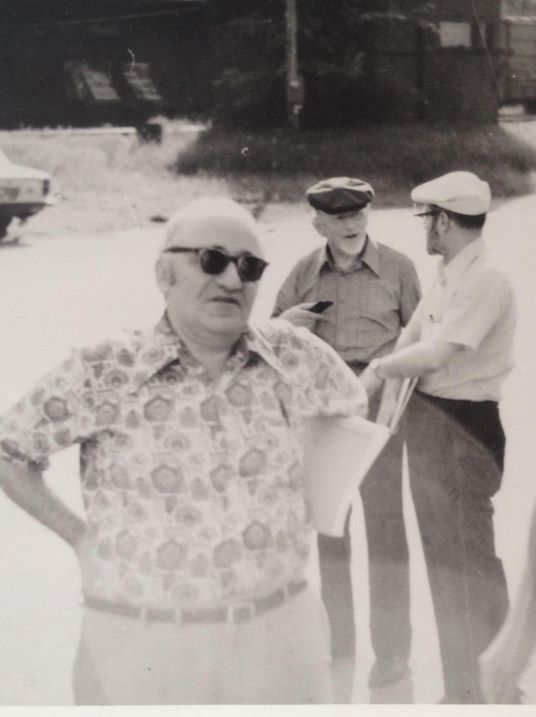

In an intellectual movement, ideas are the sine qua non, but while necessary, they are not sufficient by themselves. Intellectual movements are social phenomena, and, as such, are the results of human action but not of human design. Among the most important and significant of these human actions are the interactions of individuals in a learning environment. Succinctly, a thriving intellectual movement relies on teachers. What truly distinguished the faculty participants of the South Royalton Conference—Israel Kirzner, Ludwig Lachmann, and Murray Rothbard—is perhaps less their stature as researchers and intellectual luminaries but their stature as passionate, inspiring teachers.

I never had the pleasure of meeting Murray Rothbard or Ludwig Lachmann personally, and so I must rely on retellings. The stature of the former is widely known and attested by the devotion his students maintain to this day. For Lachmann, I rely on the witness of a smaller number who nevertheless defend his intellectual breadth and the depth of his intellectual charity. As for Kirzner, I can offer a personal anecdote. In the summer of 2006, I attended the Austrian Economics seminar at the Foundation for Economic Education (FEE) then still in Irvington-on-Hudson, NY. At that seminar, Professor Kirzner gave his famous lecture on the history of the Austrian school through the 20th century. Afterward, I waited my turn to speak with him and asked him about the equilibrating and dis-equilibrating forces of entrepreneurship in the market process. Despite the fact that he must have heard this question hundreds of times from scores of upstart graduate students, he nevertheless patiently and carefully took me through a chain of reasoning that left with me no conclusion but the one that he had written and published so often before. The carefulness of his argument, however, made less of an effect on me than his patience and willingness to engage with a student he barely knew.

Without individuals to pick up, reshape, and share them, ideas lie fallow, their fecundity preserved but unused. Just as individuals serve ideas in spanning across time and in reaching a wider audience, institutions, or organizations, allow the impact of individuals to go beyond what would normally be possible with the scant years of life we are given. Institutions can both amplify the effect of an individual and provide continuity of vision and influence well beyond that individual’s lifetime. In this respect, institutions can tie together individuals over great time and distance, allowing for this essential connection that lies at the heart of an intellectual movement.

As Richard notes, the Institute for Humane Studies sponsored the South Royalton Conference. Without significant institutional support, the conference might never have occurred. Because of the conference, connections between and among individuals were formed and, over time, flourished. With those connections came deeper understandings and a gradual expansion of the ideas at the core of the intellectual movement. Austrian economics was reborn in the wake of the South Royalton Conference and Hayek’s 1974 Nobel because ideas, individuals, and institutions came together. Austrian economics has enjoyed relative success over the last fifty years because it has, for much of that time, been both a scientific research program and a vibrant intellectual movement.

I found myself ill-at-ease upon completing Richard’s truly lovely retrospective essay because I wonder whether the same institutional structures are in place that had been for much of the past fifty years, during which the Austrian school has experienced a rebirth and resurgence. Richard’s reference to the students and early professionals gathered in Vermont back in 1974 as a “remnant” is, I suspect, a nod to the famous essay “Isaiah’s Job” by Albert Jay Nock (Nock 1936). In that essay, Nock cautions his audience not to judge success by whether they achieve popular success or acceptance. “The masses” will neither understand nor have the personal fortitude to accept a difficult or important lesson. Better, argues Nock, to live one’s own life according to said principles, rightly understood, and, if one is to reach and influence anyone else, it will be those among the remnant. The remnant, by necessity, must be a small minority of all people.

Where Nock’s essay has always sat awkwardly with me is his insistence that “the remnant will find you.” (Nock 1936, 646) Simply, I remain skeptical that Nock is correct in asserting that the remnant will manage to hear the message and find their way. But even if I concede that Nock is right about discovering ideas and finding their way to their “prophets,” I’m left wondering what we do with the remnant who have identified themselves. Do we have the institutional structures today to connect and bind together those individuals into a thriving intellectual movement?

I do not in any way begrudge Richard’s characterization of those motley individuals fifty years ago as part of the remnant; indeed they were a crucial part of a faithful remnant. What gives me unease about the current state of affairs is what we are doing to reach the remnant in our society today and what that remnant will find waiting for it beyond these bare ideas. Both the South Royalton Conference and Hayek’s Nobel sparked a renewed interest in the ideas of Austrian economics, but it was the efforts of individuals and institutions that turned those interested people into students, students into scholars, and scholars into educators.

Works Cited

Boettke, Peter J. 2012. Living Economics: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow. The Independent Institute: Oakland, CA.

Nock, Albert J. 1936. “Isaiah’s Job.” The Atlantic. Vol 157, No 6. June 1936, 641-649.

Polanyi, M. 1962. “The Republic of science.” Minerva, 1, 54–73.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.