Liberty Matters

Matters of Conscience

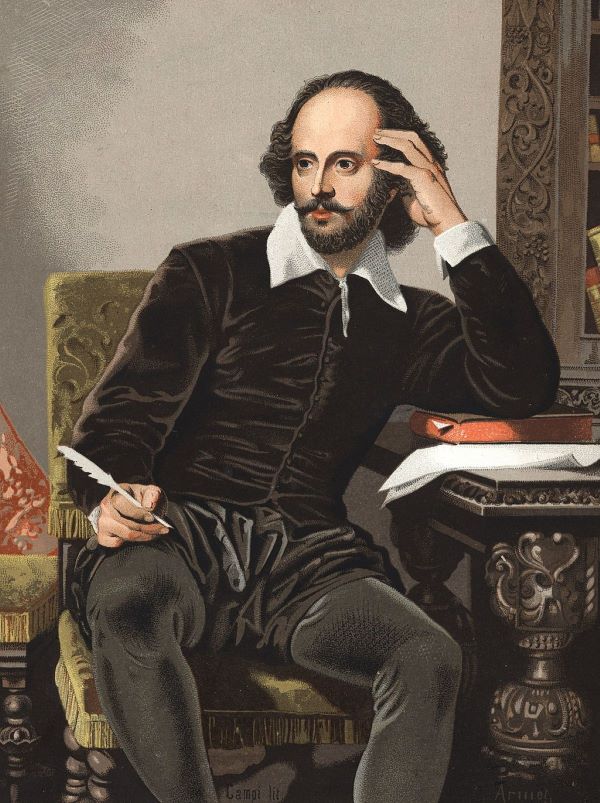

I would like again to address Shakespeare's depiction of how matters of conscience limit the extent of corruption and corrupt exercises of power. Significantly, the conscience-stricken rulers I discuss in my original response--Richard III, Macbeth, Claudio, Henry IV, Henry V, and Prospero; we could also add Lord Angelo in Measure for Measure[40] --experience their internal torture within an explicitly (or Prospero's case, implicitly) Christian context. Some 150 years later, however, Adam Smith argues forcefully that conscience operates powerfully even within persons of no belief in God:

The man who has broke through all those measures of conduct, which can alone render him agreeable to mankind, though he should have the most perfec assurance that what he had done was for ever to be concealed from every human eye, it is all to no purpose. When he looks back upon it, and views it in the light in which the impartial spectator would view it, he finds that he can enter into none of the motives which influenced it. He is abashed and confounded at the thoughts of it, and necessarily feels a very high degree of that shame which he would be exposed to, if his actions should ever come to be generally known. His imagination, in this case too, anticipates the contempt and derision from which nothing saves him but the ignorance of those he lives with. He still feels that he is the natural object of these sentiments, and still trembles at the thought of what he would suffer, if they were ever actually exerted against him. But if what he had been guilty of was not merely one of those improprieties which are the objects of simple disapprobation, but one of those enormous crimes which excite detestation and resentment, he could never think of it, as long as he had any sensibility left, without feeling all the agony of horror and remorse; and though he could be assured that no man was ever to know it, and could even bring himself to believe that there was no God to revenge it, he would still feel enough of both these sentiments to embitter the whole of his life: he would still regard himself as the natural object of the hatred and indignation of all his fellow-creatures; and, if his heart was not grown callous by the habit of crimes, he could not think without terror and astonishment even of the manner in which mankind would look upon him, of what would be the expression of their countenance and of their eyes, if the dreadful truth should ever come to be known. These natural pangs of an affrighted conscience are the dæmons, the avenging furies, which, in this life, haunt the guilty, which allow them neither quiet nor repose, which often drive them to despair and distraction, from which no assurance of secrecy can protect them, from which no principles of irreligion can entirely deliver them, and from which nothing can free them but the vilest and most abject of all states, a complete insensibility to honour and infamy, to vice and virtue. Men of the most detestable characters, who, in the execution of the most dreadful crimes, had taken their measures so coolly as to avoid even the suspicion of guilt, have sometimes been driven, by the horror of their situation, to discover, of their own accord, what no human sagacity could ever have investigated.[41]

But to what extent has the irreligious man's conscience proven efficacious against the absolute corruption Acton considered endemic to absolute power? We might consider that the worst atrocities of 20th-century dictators were committed by those who--like Marlowe's Tamburlaine--set themselves up above any divine accountability. Responding to Skwire, Alvis states, "Power made responsible is power diminished." From Shakespeare's perspective, human power is responsible to a Higher Power, and if the human power does not acknowledge this himself through virtuous self-regulation and the appropriate diminishment of power, defeat from without is inevitable. Indeed, we may say that plays like Macbeth and Richard III offer a metaphysical comfort not present in most interpretations of the modern totalitarian state.

Endnotes

[40.] See Measure for Measure 2.4.1-17:

Angelo: When I would pray and think, I think and pray To several subjects: heaven hath my empty words, Whilst my invention, hearing not my tongue, Anchors on Isabel: heaven in my mouth, As if I did but only chew his name, And in my heart the strong and swelling evil Of my conception. The state, whereon I studied, Is like a good thing, being often read, Grown fear’d and tedious; yea, my gravity, Wherein, let no man hear me, I take pride, Could I with boot change for an idle plume, Which the air beats for vain. O place! O form! How often dost thou with thy case, thy habit, Wrench awe from fools, and tie the wiser souls To thy false seeming! Blood, thou art blood: Let’s write good angel on the devil’s horn, ’Tis not the devil’s crest.

[41.] Adam Smith, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, III.2.9. Adam Smith, The Theory of Moral Sentiments. Edited by D.D. Raphael and A.L. Macfie (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1982). [Glasgow Edition], p. 118. Online Dugald Stewart edition of 1853: Adam Smith, The Theory of Moral Sentiments; or, An Essay towards an Analysis of the Principles by which Men naturally judge concerning the Conduct and Character, first of their Neighbours, and afterwards of themselves. To which is added, A Dissertation on the Origins of Languages. New Edition. With a biographical and critical Memoir of the Author, by Dugald Stewart (London: Henry G. Bohn, 1853). </titles/2620>.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.