Liberty Matters

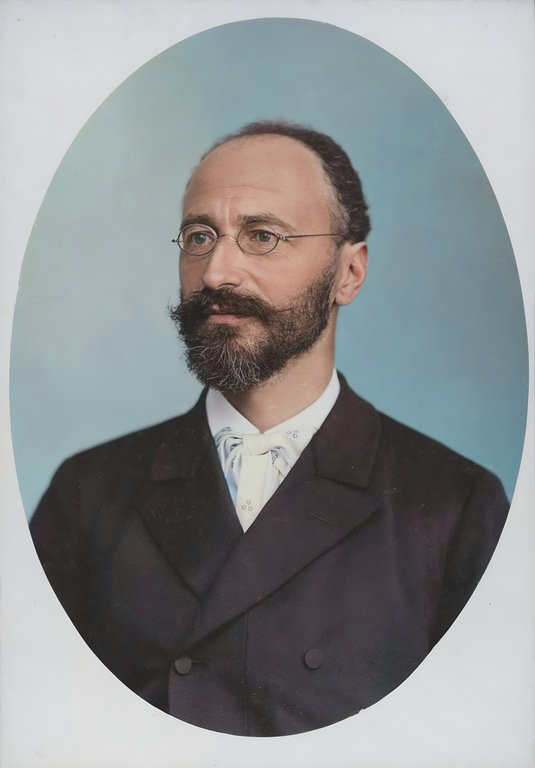

Böhm-Bawerk and J. S. Mill’s “Fourth Fundamental Proposition” on Capital

In The Pure Theory of Capital, F. A. Hayek quoted from Leslie Stephen’s 1876 book, History of English Thought in the Eighteenth Century, that John Stuart Mill’s fourth fundamental proposition on capital is a “doctrine so rarely understood, that its complete apprehension is, perhaps, the best test of an economist.”[77]

In his Principles of Political Economy, J. S. Mill presented four propositions concerning the nature and use of capital:

- “While, on the one hand, industry is limited by capital, so on the other, every increase of capital gives, or is capable of giving, additional employment to industry; and this without assignable limit.”[78]

- “To consume less than is produced, is saving; and that is the process by which capital is increased.”[79]

- “Everything which is produced is consumed, both what is saved and what is said to be spent; and the former quite as rapidly as the latter . . . To the vulgar, it is not at all apparent that what is saved is consumed . . . If they [individuals] save any part [of their income], this also is not generally speaking, hoarding, but (through savings banks, benefit clubs, or some other channel) re-employed as capital and consumed “ [Mill adds the caveat]: “If merely laid by for future use, this is said to be hoarded, and while hoarded, is not consumed at all. But if employed as capital, it is all consumed, though not by the capitalist.”[80]

- “What supports and employs productive labor, is the capital expended in setting it to work, and not the demand of purchasers for the produce of the labor when completed. Demand for commodities is not demand for labor . . . The employment afforded to labor does not depend on the purchasers, but on the capital . . . This theorem [states] that to purchase produce is not to employ labor; that the demand for labor is constituted by the wages which precede the production, and not by the demand which may exist for the commodities resulting from the production.”[81]

The first two propositions need not be presumed to be excessively controversial. As long as there are unsatisfied wants, there are always potential employments if additional means to satisfy them, “capital,” become available. And if there are to be additions to capital to facilitate the ability to expand future productive capabilities, the requisite resources must be “freed” (saved) from possible more immediate uses so they may be employed in time-consuming production processes.

But the third and fourth run counter to the entire direction of modern macroeconomics since the appearance of John Maynard Keynes’ The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money in 1936. And there have been few thorough going defenders of Mill’s four propositions in recent decades.[82]

As I attempted to explain in my earlier “response” to commentators’ remarks, Böhm-Bawerk presented his own formulation of proposition 3 (Say’s Law of Markets) in his article on “The Function of Savings.”[83] An act of savings, Böhm-Bawerk argued, was not a decision to permanently forgo a portion of an individual’s potential consumption, but rather to defer it to a future point in time. A willingness and decision to increase one’s supply of savings “today” is a means through which one manifests an increased demand for consumer goods “tomorrow.” And, thus, a decision to save opens up a profitable opportunity for entrepreneurial investment in an anticipated direction to fulfill that future greater demand.

Böhm-Bawerk’s own formulation of a version of Mill’s fourth proposition can be found in Chapter V of his Positive Theory of Capital devoted to “The Theory of the Formation of Capital.”[84] [85]

If under primitive conditions of existence an individual is to do more than merely “survive” through the sheer use of his bare hands to pick berries and attempt to catch fish in a stream, he must invest in the manufacture of “capital,” – tools – to assist in improving and increasing the productivity derivable from his human labor.

But to do so he must “save,” that is, he must out of his daily efforts to have enough for survival set aside a sufficient amount as a “store” of goods to live off to free up his time and resources that would otherwise go into immediate production for present consumption.

He uses that freed up time and resources, as Böhm-Bawerk says, to make a bow and arrows, or a canoe and fishing net, so that after the requisite “period of production” during which he has lived off his “savings,” he will have the capital goods – the intermediate tools of production – that will then assist him to increase the quantities, varieties, and qualities of the consumption goods that previously were beyond his bare labor’s potential to obtain.

In this way, he “employs himself” in making capital goods with his store of saved consumption goods to live off and his own labor diverted from more immediate berry picking and fishing with his bare hands.

The manufacture of those capital goods and their use over a period of time once in existence must logically and temporally precede the greater availability of consumer goods that that capital’s existence now makes possible.

Once produced, those consumer goods may provide previously unavailable satisfactions, but in their very consumption they are used up. And if the same consumer goods are to be available at the end of the next period, during that next period the individual must again employ himself in using the requisite resources, produced intermediate capital goods, and his own labor if the same consumer goods are to emerge at the next period’s end.

At the same time, during the production processes the capital goods produced will themselves be used up to one degree or another, so he must divert a portion of labor, time, and resource use to the maintenance of his capital goods through repair and replacement.

If he is to increase his supply of consumer goods even further from their existing amounts he must again divert an increased amount of his labor time and resource use to “investing” in more and/or better capital goods above that required to maintain his existing capital.

In Böhm-Bawerk’s framework this entails the undertaking of more time-consuming, ‘roundabout methods of production. He portrayed this in the form of a series of concentric rings, conveniently reproduced by Dr. Garrison in his earlier “response,” above, on “Böhm-Bawerk as Macroeconomist.”

Each of the rings, from the inner most ring to the outer most ring, represents a “stage of production” through which the production process passes, starting from extraction of raw materials to their transformation into a final, finished consumer good, with value added at each stage as labor and resources are combined with the as yet incomplete consumer good as it is passed on from the preceding stages leading to its final form as a useable consumption good.[86]

Of course, in “modern society” the process is more complex than presented when using Robinson Crusoe as a starting first approximation of the logic of the theory. Böhm-Bawerk briefly suggests how such a multi-period production process would be undertaken by an socialist dictator on the assumption that he possessed all the needed knowledge and the unlimited power to direct by command both men and material.

He, then, turns to how the process more like reality works in a competitive market system of independent private entrepreneurs guiding and directing the men and material they have hired, rented, or bought in the nexus of exchange.

In this market setting, Böhm-Bawerk explains, entrepreneurial decision-makers are, themselves, guided by the system of market prices that reflect the types and amounts of goods that consumers desire, and on the basis of which entrepreneurs hope to make their profits. Changes in consumer demand patterns are expressed in changes in relative prices, which then direct entrepreneurs to shift the types and amounts of goods they decide to produce.

This also applies to changes in intertemporal choices by consumers concerning their demand for consumer goods in the present versus consumer goods in the future. A decision to consume less and save more decreases current demand for goods, bringing about declines in their prices. The greater savings shows itself in the financial markets through a fall in the rate of interest, which lowers the costs of borrowing and brings about a shift to longer-term, more ‘roundabout investments that extend the time structure of production (adds to and extends the concentric rings of the stages of production).

In what way might we say that Böhm-Bawerk’s analysis is consistent with or parallel to the reasoning in Mill’s fourth fundamental proposition on capital that the, “Demand for commodities is not demand for labor”?

In my earlier response to the discussants, I highlighted Böhm-Bawerk’s debate with John Bates Clark over the nature of the capital-using process. Böhm-Bawerk had insisted that the very nature of the time structure of production means that the goods available for consumption today are goods the production of which extends backwards in time over many production periods of the past, over months or years of many “yesterdays.”

And the production processes being begun “today” and which will continue over the time periods of many “tomorrows” will only be completed and ready in the form of finished consumer goods at some point in the future.

The finished consumer goods – the “commodities” – bought today do not represent a “demand for labor” today. The entrepreneurs demanded that labor in the various stages of production at different times in the past while the consumer goods being purchased today were in the process of being produced.

And the labor being demanded “today” in the various stages of production, each stage of which represents a product at a different degree of completion and that will be, respectively, ready for sale as a consumer good at different time periods of the future, is a demand by entrepreneurs looking to future sales, not current period consumer demand for “commodities.”

But this “demand for labor” by entrepreneurs through these future-oriented stages of production is entirely dependent upon the extent to which incomes and revenues earned in the present and future periods (and the resources they represent) are partly saved and not consumed.

It is this savings of resources not being utilized for more immediate consumption purposes, that “frees” part of the productive capacity of the society to be diverted to the making and maintaining of capital, and providing the means to “advance” wages to workers who will be hired and employed in the respective processes of production for long periods of time before those specific goods in the manufacture of which they are participating will be offered for sale, and generating a revenue in the future.

Thus, it is savings that represents the greater part of the “demand for labor” in the production processes of the market and not the current period’s “demand for commodities.”

Keynes, of course, missed all this in The General Theory, because all “capital” is reduced to a homogeneous aggregate subsumed under the “marginal efficiency of capital,” and possessing no time dimension analogous to that in the “Austrian” analysis.[87]

In Keynes’ not only simplified but simplistic “macro” world, various amounts of labor and capital are waiting around “idle,” needing nothing more than “aggregate demand” spending to be increased to generate the profitability of employing more workers at institutionally “given” money wage rates, with greater aggregate output seemingly instantaneously forthcoming in the job creation’s wake. The only “time element” in the world of The General Theory is the speed with which the income multiplier operates to bring more of the unemployed into the active workplace.[88]

We, therefore, see, that Böhm-Bawerk’s conception of capital and capital using processes reinforces one of the important contributions of the “classical” economists: that it is savings that is the linchpin of production and employment, and the basis therefore of an ability to demand as a reflection of a capacity to supply.

Endnotes

[77.] F. A. Hayek, The Pure Theory of Capital reprinted in Lawrence H. White, ed., The Collected Works of F. A. Hayek, vol. 12 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press [1941] 2007), p. 388-394, especially, p. 389.

[78.] John Stuart Mill, Principles of Political Economy, with Some of Their Applications to Social Philosophy (Fairfield, NJ: Augustus M. Kelley, [1909] 1976), Book I, Chapter 5, Section 3, p. 66. Online version: The Collected Works of John Stuart Mill, Volume II - The Principles of Political Economy with Some of Their Applications to Social Philosophy (Books I-II), ed. John M. Robson, introduction by V.W. Bladen (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1965). </titles/102>.

[79.] Ibid., Book I, Chapter 5, Section 4, p. 70.

[80.] Ibid., Book I, Chapter 5, Section 5, pp. 70-71.

[81.] Ibid., Book I, Chapter 5 Section 9, pp. 79-80.

[82.] The exception has been Steven Kates, Say’s Law and the Keynesian Revolution: How Macroeconomic Theory Lost Its Way (Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar, 1998), pp. 68-73; Kates, Free Market Economics: An Introduction for the General Reader (Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar, 2011), pp. 74-80; Kates, “Mill’s Fourth Fundamental Proposition on Capital: A Paradox Explained,” Selected Works of Steven Kates (January 2012), <http://works.bepress.com/stevenkates/2>.

[83.] Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk, “The Function of Savings,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences (May 1901), reprinted in Richard M. Ebeling, ed., Austrian Economics: A Reader (Hillsdale, MI: Hillsdale College Press, 1991) pp. 401-413.

[84.] Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk, Capital and Interest, Vol. 2: Positive Theory of Capital (South Holland, Ill: Libertarian Press, [1889] 1959), pp. 102-118; or the earlier William Smart translation, The Positive Theory of Capital (Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press, [1891] 1971), pp. 106-118. Smart translation is online: Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk, The Positive Theory of Capital, trans. William A. Smart (London: Macmillan and Co., 1891). Book II, Chapter V: Formation of Capital in a Community </titles/283#Boehm-Bawerk_0183_236>.

[85.] This not to suggest that Böhm-Bawerk was consciously or intentionally attempting to formulate his own version of Mill’s argument. But, rather, the reasoning in Böhm-Bawerk’s own exposition is consistent with or parallel to the logic of Mill’s statement. There are, in fact, few references to Mill throughout The Positive Theory of Capital, and none directly related to Mill’s four fundamental propositions on capital.

[86.] Later, Hayek conveyed the same logic of a time-structure of production in his famous “triangles” in chapter II of Prices and Production [1931] reprinted in Hansjoerg Klausinger, ed., The Collected Works of F. A. Hayek, Vol. 7: Business Cycles, Part I (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012), pp. 227-241.

[87.] John Maynard Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, reprinted in, The Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes, Vol. VII (London: MacMillan [1936] 1973).

[88.] Hayek had, already, in his detailed and lengthy critique of Keynes’ earlier, A Treatise on Money, 2 vols. (1930), pointed out the superficial and inadequate conceptions of capital that occupied Keynes’ mind. See, F. A. Hayek, “Reflections on the Pure Theory of Money of Mr. J. M. Keynes,” Pts. I and II, Economica (Nov. 1931 & February 1932), reprinted in, Bruce Caldwell, ed., The Collected Works of F. A. Hayek, Vol. IX: Contra Keynes and Cambridge: Essays and Correspondence (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995) pp. 121-146 & 174-197.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.