Liberty Matters

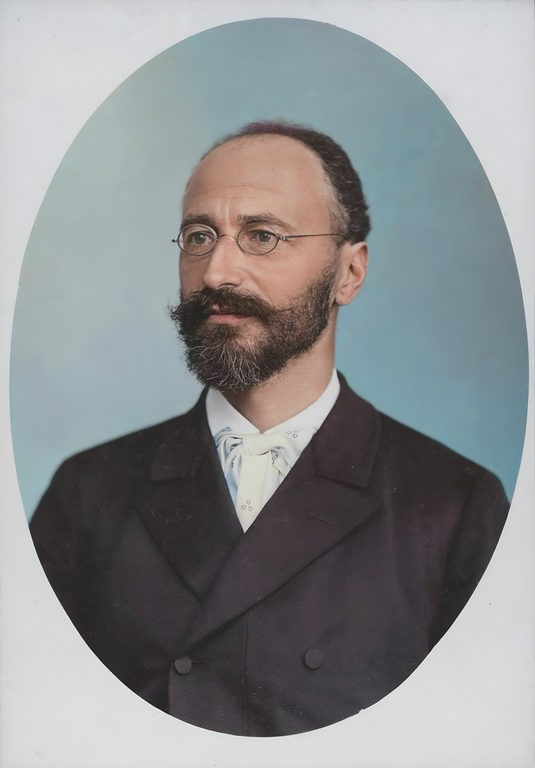

Böhm-Bawerk’s Enduring Legacy: The Pricing Process, the Savings-Investment Nexus, and the Capital Structure in the Context of Time

I want to thank the three discussants for their insightful remarks, all of which filled in many aspects of an appreciation of Böhm-Bawerk that I could not attempt in my brief overview of his life and contributions.

I want to thank the three discussants for their insightful remarks, all of which filled in many aspects of an appreciation of Böhm-Bawerk that I could not attempt in my brief overview of his life and contributions.I.

Dr. Joseph Salerno, in his response, “Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk: Pioneer of Causal-Realist Theory,” highlights an essential element to Böhm-Bawerk’s exposition of the theory of value and price.

In the standard, textbook explanations of the determination of market equilibrium price, it is assumed that individuals are offered a set of alternative prices, to which they respond by informing the “price-giver” how much they would be interested in either buying or selling at those alternative prices.

Having derived each individual’s price schedule as buyer and seller, the price-giver adds up the respective supply and demand schedules for each good in each market, and then determines at what set of prices would each and every market be in market-clearing equilibrium.

The “Austrians” followed a different route for explaining the emergence of market prices and their tendency toward a market-clearing balance. Theirs has been what one leading Austrian economist of the interwar period referred to as the “causal-genetic” approach to price theory.[57]

That is, it is an attempt to explain the causal origin of price out of the individual subjective valuations of the market participants, and how out of these subjective valuations prices emerge and are formed on the market. [58]

In Böhm-Bawerk’s world, individuals enter the market knowing the quantity of the goods they have for sale and what it is they may wish to buy. But each individual has only a clouded conception concerning the maximum price they might be willing to pay to buy or the minimum price they might accept in order to sell.

All the resulting market actions are, now, grounded in people’s expectations – expectations about the degree to which the good they might purchase is important to their future well-being, and therefore the intensity of the marginal significance that the good has for them.

There would begin to take form in the individual’s mind the maximum bid that he might be willing to make to acquire it; and as he starts to interact with others in the market, he will form an expectation of what minimum price he would have to bid to successfully beat out his closest rival in the contest of purchasing the good.

Similar expectations would be at work in the minds of those on the supply-side about the minimum price they would accept to part with the good, if necessary, and what maximum price they could ask, without running the risk of losing the sale to a more eager competitor also anxious to make a sale.[59]

It is only in the interactions of the market process that men discover actually how much they value what they could buy or how little they value what they could sell. In Böhm-Bawerk’s world, the traders initiate the bids and offers. They decide whether they value a good more than they originally thought, so as not to lose out to the next most interested buyer who also wants to purchase that desired commodity.

Up goes the price, with each transactor deciding if the latest bid by one of his demand-side rivals has pushed the price up to the maximum threshold at which he chooses to bow out, due to the price now being greater than what he thinks that good to be worth at the margin.

The same process plays itself out on the supply-side, with suppliers eager to not miss out on a profitable sale by allowing one of their rivals to underbid him. Each weighs whether or not the price has reached a minimum below which it is not worth selling and becomes better to hold on to the good for some other use or purpose.

The two-sided competition continues until a price range has been reached within which all willing buyers on the demand-side are successfully matched with willing sellers on the supply-side.

Böhm-Bawerk’s version of an auction was clearly only a first approximation of the actual complexity of price formation in the developed market process. But it is one in which the actors make the bids and offers; they initiate the actions that form the prices they finally bring markets into balance. They do not passively rely upon a “price-giver.”

Böhm-Bawerk’s actors have reflective minds, they evaluate what things might be worth to them, what they might have to bid or offer to get it, and how far it is worth going in the actual interchange and process of market competition before deciding to fall by the wayside under the pressure of some rival with a demand to buy or a willingness to sell more intense than their own.

Through this “causal-genetic” market process approach, Böhm-Bawerk attempted to demonstrate that “price is, from beginning to end the product of subjective valuation.”[60] The evaluating logic of active individual human minds is the foundational starting-point from which insights into the workings of the complex market order arise.

Or as Carl Menger expressed it – and which Böhm-Bawerk adopted as his own method of analysis – the task is to “reduce the complex phenomena of human economic activity to the simplest elements that can still be subjected to accurate observation [individual acting man], apply to these elements the measure corresponding to their nature, and constantly adhering to this measure, to investigate the manner in which the most complex economic phenomena evolve from their elements according to definite principles”[61]

Through this method the Austrians combined methodological individualism with a methodological subjectivism that analyzes social and market processes from the respective actors’ points-of-view with all of their intended and unintended consequences.[62]

(It is in Philip Wicksteed’s, The Common Sense of Political Economy (1910) that one finds the logical next step of the “Austrian” analysis of price formation, in which he explains how in the division of labor it is the retail entrepreneurs who set prices for the trading day based on their appraisement of consumers’ demands when potential buyers only appear in the market in sequence over the trading period. And how discovery of errors in anticipating that consumers’ demand at the end of the trading period brings about changes in prices in the next trading period, and influences the demand for goods at the wholesale level and then for the factors of production up through the stages of production.)[63]

II.

Roger Garrison’s commentary focuses on “Böhm-Bawerk as Macroeconomist.” As Dr. Garrison says, Austrian economists have tended to eschew the term “macroeconomics” due to its identification with Keynesian Economics. Yet, the link between the “micro” and the “macro” has been a central part of much of modern Austrian Economics.

This is most clearly seen in the writings of the Austrians on money and the business cycle over the last one hundred years. Their approach has been to ask what is the institutional connecting link between the interactions and outcomes in individual markets and the systemic periodic fluctuations in production, output and employment over the economy as a whole?

They have seen that linchpin in the monetary system, since money is the one commodity that is on one side of every exchange. Changes in the supply of and the demand for money, therefore, can send out disturbing repercussions throughout the entire market system.

The Austrian theory of monetary dynamics focuses on the fact that such changes, especially in the supply of money, do not simply work their effect on the economy through changes in the general purchasing power of the monetary unit (the “price level”). Their emphasis has been on the sequential-temporal process through which the structure of relative prices and wages are modified, starting from the specific “microeconomic” point in the market where the change in the quantity of money is injected (or withdrawn) from the economic system.

As Dr. Garrison points out, Böhm-Bawerk never extended his analysis to the area of money and the business cycle. But Böhm-Bawerk did see the relevance of such investigations. As he once said:

A theory of crisis can never be an inquiry into just one single phase of economic phenomena. If it is to be more than an amateurish absurdity, such an inquiry must be the last, or the next to last, chapter of a written or unwritten economic system. In other words, it is the final fruit of knowledge of all economic events and their interconnected relationships.[64]

Perhaps it was his untimely death at the relatively young age of 63 that prevented Böhm-Bawerk adding such a final chapter to his own body of published works. As it was, this was a task taken up by later Austrians, especially first Ludwig von Mises and then Friedrich A. Hayek.[65]

Nonetheless, there was one aspect of the modern macroeconomic arena of theoretical controversy that Böhm-Bawerk did take up at the start of the 20th century: the role of savings in influencing economic activity and the relevancy of Say’s Law of Markets.

In the 1920s and 1930s, there arose the notion of the ”paradox of savings.”[66] While it is rational and reasonable for any one individual to set aside apart of his income for future uses and planned expenditures, if a wide segment of the income-earning community were to do so, this very act of increased economy-wide savings would “paradoxically” diminish the demand for investment.

An economy-wide increase in savings by necessity implies an economy-wide decrease in consumption. But if the consumer demand for final output decreases, what then happens to the profit motive for undertaking greater investment projects that would lead to even greater over-capacity of production facilities?

An economist named L. G. Bostedo leveled this charge against Böhm-Bawerk in 1900. Bostedo argued that since market demand stimulates manufacturers to produce goods for the market, a decision by income-earners to save more and consume less destroys the very incentive for undertaking the new capital projects that greater savings are supposed to facilitate. He concluded that greater savings, rather than an engine for increased investment, served to retard investment and capital formation.[67]

The following year, 1901, in “The Function of Savings,” Böhm-Bawerk replied to this criticism.[68] “There is lacking from one of his premises a single but very important word, “ Böhm-Bawerk pointed out. “Mr. Bostedo assumes . . . that savings signifies necessarily a curtailment in the demand for consumption goods.” But, Böhm-Bawerk continued:

Here he has omitted the little word "present." The man who saves curtails his demand for present goods but by no means his desire for pleasure-affording goods generally . . .The person who saves is not willing to hand over his savings without return, but requires that they be given back at some future time, usually indeed with interest, either to himself or his heirs.Through savings not a single particle of the demand for goods is extinguished outright, but, as J. B. Say showed in a masterly way more than one hundred years ago in his famous theory of the ‘vent or demand for products,’ the demand for goods, the wish for means of enjoyment is, under whatever circumstances men are found, insatiable. A person may have enough or even too much of a particular kind of goods at a particular time, but not of goods in general nor for all time. The doctrine applies particularly to savings.For the principle motive of those who save is precisely to provide for their own futures or for the futures of their heirs. This means nothing else than that they wish to secure and make certain their command over the means to the satisfaction of their future needs, that is, over consumption goods in a future time. In other words, those who save curtail their demand for consumption goods in the present merely to increase proportionally their demand for consumption goods in the future.[69]But even if there is a potential future demand for consumer goods, how shall entrepreneurs know what type of capital investments to undertake and what types of greater quantities of goods to offer in preparation for that higher future demand?

Böhm-Bawerk 's reply was to point out that production is always forward-looking, a process of applying productive means today with a plan to have finished consumer goods for sale tomorrow. The very purpose of entrepreneurial competitiveness is to constantly test the market, so as to better anticipate and correct for existing and changing patterns of consumer demand. Competition is the market method through which supplies are brought into balance with consumer demands. And if errors are made, the resulting losses or less than the anticipated profits act as the stimuli for appropriate adjustments in production and reallocations of labor and resources among alternative lines of production.

When left to itself, Böhm-Bawerk argued, the market successfully assures that demands are tending to equal supply, and that the time horizons of investments match the available savings needed to maintain the society's existing and expanding structure of capital in the long run.[70]

III.

Dr. Peter Lewin brings out that Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk was “A Man for His Time, and Ours.”

The significance of time and its meaning in the market process is emphasized by Dr. Lewin in his comments. And as he rightly points out, the “time element” was crucial to Böhm-Bawerk’s theory of capital and interest.

The meaning of capital and its relationship to the passing of time was central, for example, to Böhm-Bawerk’s debates with the American economist, John Bates Clark. In a nutshell, Clark suggested conceiving of capital as a perpetual “fund” that reproduces itself as concrete elements of this “fund” – specific capital goods – are used up.

In this conceptual setting, time and the notion of a period of production is irrelevant and meaningless, in Clark’s view. There is no “waiting” for production to generate output because both are happening simultaneously. He visualized a forest in which there are rows of trees of varying maturity. As one row of trees are cut down and harvested another row of saplings are being planted. And as long as this “synchronization” of simultaneous investment and consumption continues the fund of trees remains constant and having trees to harvest next year requires no waiting today or tomorrow.

Böhm-Bawerk responded that there is no “fund” of capital independent of the individual capital goods organized in complementary relationships of productive use through a sequence of interconnected stages of production leading to a final finished consumption good.

The “synchronization” that creates the conceptual illusion of no waiting because consumption and production are occurring at the same time, is due to time-laden decisions to choose to replant a row of sapling trees as a mature row of trees is harvested, period after period of time.

The trees harvested and used “today” are not the ones planted simultaneously in the present. The trees cut down now are the trees planted ten or twenty or more years earlier. A time decision had to be made in the past that it would be worth foregoing the resources and actions that might have been used for other things at that earlier time, and planting those trees instead and “waiting” for the “reward” of what those trees would enable to be done in the future when they had reached a certain stage of maturity.

Any break or disruption in the repeated decision-making and actions that have been made in the past and that hid from clearer view the conscious time-related choices of resource use and intertemporal trade-offs would soon show the reality of stages and time-structures of production activity precisely because the presumed “equilibrium” relationships taken for granted by Clark would no longer hold.[71]

The meaning of time and its “periods” has required a particular conceptual turn when looked at through the Austrian subjectivist perspective. Dr. Lewin suggests some of the implications of this in his remarks.

Ludwig von Mises attempted to highlight the meaning and relevance of time periods within a methodological subjectivist approach. All action occurs in and is inseparable from time. All action implies a before and an after, a sooner and a later, a becoming and a became.

This means that it is impossible for man to be indifferent to the passing of time, Mises said. Indeed, it is in the contemplation of action that man becomes most conscious of time. And in Mises’ view, it is the “potential for action” that delineates the past from the present and the present from the future. Mises argued:

That which can no longer be done or consumed because the opportunity for it has passed away, contrasts the past with the present. That which cannot yet be done or consumed, because the conditions for undertaking it or the time for its ripening have not yet come, contrasts the future with the past.The present offers to acting opportunities and tasks for which it was hitherto too early and for which it will be hereafter too late. The present qua duration is the continuation of the conditions and opportunities given for acting. Every kind of action requires special conditions to which it must be adjusted with regard to the aims sought. The concept of the present is therefore different for various fields of action. It has no reference whatever to the various methods of measuring the passing of time by spatial movements. The present contrasts itself, according to the various actions one has in view, with the Middle Ages, with the nineteenth century, with the past year, month, or day, but no less with the hour, minute, or second just passed away.If a man says: Nowadays Zeus is no longer worshipped, he has a present in mind other than that of the motorcar driver who thinks: Now it is still too early to turn. And as the future is uncertain it is always undecided and vague how much of it we can consider as now and present. If a man had said in 1913: At present – now – in Europe freedom of thought is undisputed, he would have not foreseen that this present would very soon be a past. [72]

In this conception of time, individuals pursuing various goals invariably operate simultaneously in terms of "periods" of varying length. Each action has its own time horizon. For some plans, the actor is in the middle of the "present" period; for other plans, the "present" period is coming to a close; for yet other plans the "future" period is just becoming the "present." For still other plans, the potentials for action are still in a "future" period.

Nor are these periods of equal length. For some actions, the "present" period is an instant as measured by the movement of the clock, and then is gone; for other actions, the "present" extends far into the future as measured by the clock. Each planning period would have its sub-periods divided into "past," "present" and "future" (for instance, "Right now I'm working on my undergraduate degree" would have the sub-period, "Right now I'm in my first year," which would have the sub-period "Right now I'm having lunch in between my morning and afternoon classes").

In the market changes usually do not impact simultaneously on all transactors. Instead, a change in market conditions originates at some point in the economic system. From this "epicenter" the consequences of the change, in terms of changes in the actions and plans of those initially impacted, emanates out in a particular path-dependent sequential and temporal order. Some individuals in the social system of division of labor will be affected by this – to a greater or lesser extent – at a different time than others; some individuals may be impacted at the same time; some will be impacted sooner, others later. At each of those moments at which the change reaches each individual, each of them will have to weigh the meaning and significance of the change in terms of requiring a "change in plans," that is in terms of when, how and how much.

How one fully integrates such a subjectivist orientation and framework into the problems and analysis of the market process, into the capital structure and investment, and the dynamics of the business cycle and general economic development and change is the challenging legacy left to us by Böhm-Bawerk and those others who followed him in extending and refining the Austrian Economics tradition.

Endnotes

[57.] Hans Mayer, “The Cognitive Value of Functional Theories of Price: Critical and Positive Investigations Concerning the Price Problem” [1932], translated in, Israel M. Kirzner, ed., Classics in Austrian Economics: A Sampling in the History of a Tradition, Vol. II: “The Interwar Period” (London: William Pickering, 1994) pp. 55-168, especially p. 57.

[58.] Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk, Capital and Interest, Vol. II: The Positive Theory of Capital (South Holland, Ill: Libertarian Press, 1959) pp. 203-222.

[59.] Ibid., pp. 240-243.

[60.] Ibid., p. 225.

[61.] Carl Menger, Principles of Economics (New York: New York University Press, [1871] 1981), p. 46.

[62.] On the development and ideas of the Austrian School from the 1870s to the First World War, and in comparison to the “Neoclassical” economics tradition of that time, see, Richard M. Ebeling, “An ‘Austrian’ Interpretation of the Meaning of Austrian Economics: History, Methodology, and Theory,” Advances in Austrian Economics, Vol. 14 (2010) pp. 43-68.

[63.] Philip Wicksteed, The Common Sense of Political Economy (New York: Augustus M. Kelley, [1910] 1969), pp. 218-236.

[64.] Quoted in Ludwig von Mises, “Monetary Stabilization and Cyclical Policy” [1928] in On the Manipulation of Money and Credit (Dobbs Ferry, NY: Free Market Books, 1978) pp. 61-62.

[65.] For an exposition of the Austrian theory of money, credit and the business cycle, with a comparison to the Keynesian approach in the context of explaining the causes and “cures” for the Great Depression, see, Richard M. Ebeling, Political Economy, Public Policy, and Monetary Economics: Ludwig von Mises and the Austrian Tradition (New York: Routledge, 2010), Chapter 7: “The Austrian Economists and the Keynesian Revolution: The Great Depression and the Economics of the Short-Run,” pp. 203-272.

[66.] For an “Austrian” explanation and critique of the idea of the “paradox of thrift,” see, F. A. Hayek, “The Paradox of Savings,” in Profits, Interest and Investment, and Other Essays on the Theory of Industrial Fluctuations (New York: Augustus M. Kelley, [1939] 1969). Pp. 199-263.

[67.] L. G. Bostedo, “The Function of Savings,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences (January, 1900), reprinted in Richard M. Ebeling, ed., Austrian Economics: A Reader (Hillsdale, MI: Hillsdale College Press, 1991) pp. 393-400.

[68.] Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk, “The Function of Savings” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences (May, 1901), reprinted in Richard M. Ebeling, ed., Austrian Economics: A Reader (Hillsdale, MI: Hillsdale College Press, 1991), pp. 401-413.

[69.] Ibid., p. 407.

[70.] Ibid., pp. 408-412.

[71.] Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk, “The Positive Theory of Capital and Its Critics, I: Professor Clark’s Views on the Genesis of Capital,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, January 1895, pp. 113-31; “The Origin of Interest,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, July 1895, pp. 380-87; “Capital and Interest Once More: I. Capital vs. Capital Goods,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, November 1906, pp. 1-21; “Capital and Interest Once More: II. A Relapse to the Productivity Theory,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, February 1907, pp. 247-82; and, “The Nature of Capital: A Rejoinder,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Nov. 1907, pp. 28-47; and by John Bates Clark, “The Genesis of Capital,” Yale Review, November 1893, pp. 302-315; “The Origin of Interest,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, April 1895, pp. 257-78; “Real Issues Concerning Interest,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, October 1895, pp. 98-102; and “Concerning the Nature of Capital: A Reply,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, May 1907, pp. 351-70.

[72.] Ludwig von Mises, Human Action: A Treatise on Economics (Chicago, Ill: Henry Regnary, 3rd revised ed., 1966) pp. 100-101.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.