Liberty Matters

Böhm-Bawerk as Macroeconomist[44]

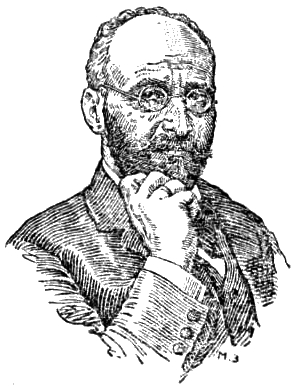

Despite the fact that many Austrian-oriented economists have an aversion to the term “macroeconomics,” I begin this essay with the claim that Eugen von Böhm‑Bawerk was a macroeconomist ‒ and a self‑reflective one at that. Richard Ebeling’s short sections on Böhm‑Bawerk’s theorizing about capital and interest give me a hook for making and justifying this claim. The classical economists, especially David Ricardo, could in retrospect be considered macroeconomists in an era that predates any specific attention to the micro/macro distinction. The word “macroeconomics,” of course, is a relatively modern one. It was Paul Samuelson who almost singlehandedly reorganized the subject matter of economics on the basis of a first‑order distinction between micro and macro, perversely putting macro ahead of micro in the pedagogical sequence. Samuelson traced the distinction itself to Ragnar Frisch and Jan Tinbergen and attributed the word’s debut in print to Erik Lindahl in 1939.[45]

However, in an 1891 essay titled “The Austrian Economists,” Böhm‑Bawerk wrote that “[o]ne cannot eschew studying the microcosm if one wants to understand properly the macrocosm of a developed economy.”[46] Packed into this understated methodological maxim are both his goal of understanding the macroeconomy and his judgment that microeconomic foundations are essential for ‒ and prerequisite to ‒ a viable macroeconomics. This is a view that, in mainstream economics, dates back only to the mid-1960s, a period during which the full-blown (mostly Keynesian) macro structure was in search of its own microfoundations.

Böhm-Bawerk’s Bull’s-Eye Figures

The critical aspect of the microcosm that Böhm-Bawerk had in mind was the micro-movements affecting the economy’s production activities that were brought about by changes in people’s saving behavior. Curiously, he represented those production activities as a sequence of concentric rings ‒ the innermost rings marking the beginnings of the production processes and the outermost rings representing the eventual maturation of those processes. The rings, then, stood for “maturity classes” of capital goods with the final class maturing into consumable output. (The initiation of the production processes evidently sprang from entrepreneurial actions at the center of the figure.) Fig. 1 and Fig. 2, which actually appear on opposing pages in Capital and Interest, depict a well-developed economy with ten maturity classes and a less-well-developed economy with only five.[47]

These bull’s-eye figures may have been just right for capturing the readers’ gaze, but they function rather poorly as analytical devices. Nevertheless, Böhm-Bawerk made the most of them by posing a question about the nature of the market forces that govern the allocation of resources among the various rings. Let me paraphrase his key question here: “What changes in the microcosm would we expect to see on the occasion of a saving-induced increase in capital creation?” The answer to this key question, which distinguishes Austrian macroeconomics from what would later become mainstream macroeconomics, involves a change in the configuration of the concentric rings. Several sorts of changes are suggested, each entailing the idea that increased saving (which puts downward pressure on interest rates) spurs investment in the inner rings and reins in investment in the outer rings (which in turn tempers near-term consumption output and allows for increased future consumption output). Böhm‑Bawerk also indicates that in a market economy it is the entrepreneurs who bring such structural changes about and that their efforts are guided by movements in interest rates and changes in the relative prices of capital goods in the various maturity classes.[48]

Note that the mainstream’s untimely search for the microeconomic foundations of macroeconomics did not focus at all on the market mechanisms that Böhm-Bawerk saw so clearly. And with other mainstream developments, such as theorizing in terms of a “representative agent” (instead of in terms of competing entrepreneurs), invoking the assumption of so-called “rational expectations” and, later, re-inventing macro as “stochastic dynamic general equilibrium modeling”), the search for meaningful foundations was effectively called off.

It is easy for modern Austrian economists to see that Böhm‑Bawerk was just a step away from articulating the Austrian theory of the business cycle ‒ a step that was taken by Ludwig von Mises ([1912] 1953) without the benefit of a graphical representation and by F. A. Hayek ([1935] 1967) with the benefit of his triangular figures. The critical step entails the comparison of changes in the configuration of the Böhm-Bawerkian rings (or of the Hayekian triangle) on the basis of whether those changes were saving‑induced or policy‑induced. A change in intertemporal preferences in the direction of increased saving reallocates capital among the maturity classes (or stages of production) such that the economy experiences capital accumulation and sustainable growth; a policy‑induced change in credit conditions, that is, a lowering of the interest rate achieved by the central bank’s lending of newly created money, misallocates capital among the rings (or stages) such that the economy experiences unsustainable growth and hence an eventual economic crisis.

Development of the theory in this direction was beyond Böhm‑Bawerk for the simple reason that he never ventured into monetary theory. His attitude toward monetary theory is revealed in letters to Swedish economist, Knut Wicksell,[49] whose ideas about the divergence of the market rate of interest and the natural rate was to become an important part of the Austrian theory. In 1907, Böhm-Bawerk wrote: “I have not myself given thought to or worked on the problem of money as a scholar, and therefore I am insecure vis‑à‑vis this subject.” And in 1913, a year before his death: “I have not yet included the theory of money in the subject‑matter of my thinking, and I therefore hesitate to pass a judgment on the difficult questions it raises” ‒ this hesitation despite the fact that Mises, Böhm-Bawerk’s and Wieser’s student, had published his Theory of Money and Credit the year before.

On Böhm‑Bawerk’s Contribution to Capital Theory and Capital-Based Macroeconomics

We might ask: Is Böhm-Bawerk’s Positive Theory a precise and definitive statement of the economic relationships that constitute capital theory as it pertains to macroeconomics, or is it a crude, skeletal and nonsense-laden outline of these relationships? Assessments can be found to support either view:

Böhm‑Bawerk’s scientific work forms a uniform whole. As in a good play each line furthers the plot, so with Böhm‑Bawerk every sentence is a cell in a living organism, written with a clearly outlined goal in mind…. And this integrated plan was carried out in full. Complete and perfect his lifework lies before us. There cannot be any doubt about the nature of his message.

Alternatively:

Böhm‑Bawerk’s work [was not] permitted to mature: it is essentially (not formally) a first draft whose growth into something much more perfect was arrested and never resumed. Moreover, it is doubtful whether Böhm‑Bawerk’s primitive technique and particularly his lack of mathematical training could have ever allowed him to attain perfection. Thus, the work, besides being very difficult to understand, bristles with inadequacies that invite criticism ‒ for instance, as he puts it, the “production period” is next to being nonsense ‒ and impedes the reader's progress to the core of his thought.

These two passages provide a remarkable contrast, all the more remarkable when it is realized that both were written by one and the same Joseph A. Schumpeter.[50]

For sure, Böhm-Bawerk’s Capital and Interest served as an important stepping stone between Menger’s Principles and the works of twentieth-century Austrian-oriented economists ‒ this despite Menger’s claim that “[T]he time will come when people will realize that Böhm‑Bawerk’s theory is one of the greatest errors ever committed”[51] But what, exactly, was the nature of that “greatest error”? And why have modern schools of thought (Keynesian, monetarist, new classicism, SDGE modeling) turned a blind eye to the Austrian notion of a multi-stage, time-consuming structure of production? These and related issues may be ripe for discussion on this online forum.

Endnotes

[44.] Parts of this essay consist of condensed or elaborated material from Garrison (1990) and Garrison (1999).

[45.] Samuelson, Paul A. “Credo of a Lucky Textbook Author,” p. 157.

[46.] Hennings, Austrian Theory of Value and Capital, p. 74. The fact that Böhm-Bawerk issued so few methodological pronouncements makes this one all the more striking.

[47.] Böhm-Bawerk, Capital and Interest, vol. 2, pp. 106 and 107. Though rarely reproduced or discussed in modern assessments of Böhm-Bawerk, these figures, or rather the micro-level movements that they are supposed to illustrate, are central to his vision of a capital-using economy. Note that the numbering of the maturity classes (e.g., from 10 to 1 rather than from 1 to 10) conforms with Menger’s ordering of goods: Böhm-Bawerk’s least mature class is Menger’s highest-order goods.

[48.] Böhm-Bawerk, Capital and Interest, vol. 2, p. 112.

[49.] Forty letters from Böhm-Bawerk to Wicksell (1893-1914) are included as an Appendix to Hennings, The Austrian Theory of Value and Capital.

[50.] The first‑quoted passage was written on the occasion of Böhm‑Bawerk’s death: Schumpeter, 1951, p. 146; the second‑quoted passage is from Schumpeter, 1954, p. 847.

[51.] Schumpeter, 1954, p. 847, n. 8.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.