Liberty Matters

Spencer and Mill

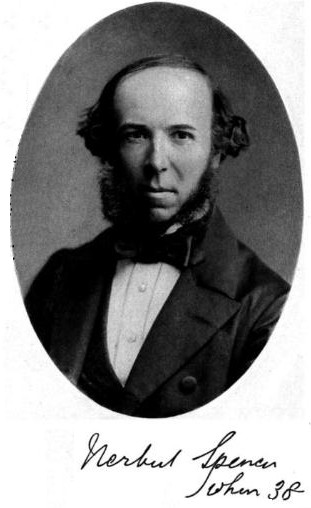

Herbert Spencer and John Stuart Mill have a great deal in common. Both tried to base a self-realizationist ethics and a secular, rights-based classical-liberal political theory on indirect-utilitarian moral theory, classical economics, and associationist psychology; and both accepted a historical theory of progressive human socialization. Yet their reputations are vastly different.

Herbert Spencer and John Stuart Mill have a great deal in common. Both tried to base a self-realizationist ethics and a secular, rights-based classical-liberal political theory on indirect-utilitarian moral theory, classical economics, and associationist psychology; and both accepted a historical theory of progressive human socialization. Yet their reputations are vastly different.In the academic mainstream, Mill is honored while Spencer is vilified. Crane Brinton famously said that Mill humanized utilitarianism while Spencer barbarized it[137] – a rather ironic choice of words given Spencer’s hostility to rebarbarization. In right-wing circles, it is often Mill who is vilified as an alleged totalitarian[138] while Spencer is largely ignored. And among libertarians, Spencer is often praised as the consistent libertarian while Mill is dismissed as a confused middle-of-the-roader whose views represent the beginning of the slide from classical liberalism to welfare liberalism.

Ludwig von Mises, for example, writes:

John Stuart Mill is an epigone of classical liberalism and, especially in his later years, under the influence of his wife, full of feeble compromises. He slips slowly into socialism and is the originator of the thoughtless confounding of liberal and socialist ideas that led to the decline of English liberalism and to the undermining of the living standards of the English people.[139]

Murray Rothbard, for his part, calls Mill a “woolly minded man of mush” and “flabby and soggy ‘moderation’” whose “graceful and lucid style ... served to mask the vast muddle of his intellectual furniture.”[140] Bryan Caplan agrees that Mill’s thought is “shockingly muddled.”[141] And even Alberto writes, earlier in the conversation, that when we “compare him with his contemporary John Stuart Mill,” Spencer “stands out clearly as an adamant proponent of libertarianism.”

While there are certainly important differences between Spencer and Mill, I’m inclined to think that the extreme contrast between them is overstated. The mainstream academic narrative of a humanitarian Mill and a callous, brutal Spencer fails to account for issues, such as colonialism, on which Spencer was more humanitarian than Mill. On the other hand, the libertarian narrative of a private-property purist Spencer and a socialist-leaning Mill faces several difficulties. On some issues (such as land-ownership), Mill is a greater defender of private property than Spencer is; most of Mill’s “socialism” amounts to a defense of workers’ cooperatives rather than state control, and is very similar to Spencer’s views on the same topic; and Spencer’s strong libertarian principles are moderated in their present application by his historical relativism. On issues where the two broadly agree, sometimes it is Mill who is more insightful and nuanced (as on feminism), though by no means always. (Also, what Rothbard and Caplan see as Mill’s muddle-headedness I’m inclined to see as mere complexity.) We would do better to learn from both Mill and Spencer than to try to cast one as angel and the other as demon.

Endnotes

[137.] Quoted in Dante Germino, Machiavelli to Marx: Modern Western Political Thought (University of Chicago Press, 1972), p. 256.

[138.] See, e.g., Joseph Hamburger, John Stuart Mill on Liberty and Control (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2001) and Linda C. Raeder, John Stuart Mill and the Religion of Humanity (Columbia, Mo.: University of Missouri Press, 2002).

[139.] Ludwig von Mises, Liberalism: The Classical Tradition, trans. Ralph Raico, ed. Bettina Bien Greaves (Indianapolis, Ind.: Liberty Fund, 2005), Appendix 1. </titles/1463#Mises_0842_502>

[140.] Murray N. Rothbard, Classical Economics: An Austrian Perspective on the History of Economic Thought, Volume II (Auburn, Ala.: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2006), pp. 277-78. <https://mises.org/sites/default/files/Austrian%20Perspective%20on%20the%20History%20of%20Economic%20Thought_Vol_2_2.pdf>

[141.] Bryan Caplan, “The Awful Mill,” EconLog, March 23, 2012. <https://www.econlib.org/econlog/archives/2012/03/the_awful_mill.html>.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.