Liberty Matters

Spencer’s Conservative Turn?

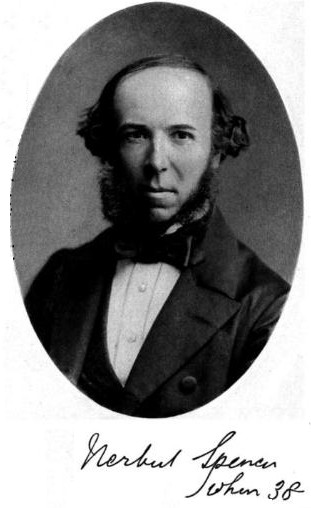

It has often been suggested that Spencer grows more conservative over time; and I think there is some truth to this. One sign of a conservative turn is the increasing moderation (though never abandonment) of his feminist commitments: contrast the radical character of his chapter on women’s rights in his 1850 Social Statics[110] with the more watered-down account in the 1897 Principles of Ethics,[111] or his ludicrous 1891 assertion that “throughout our social arrangements the claims of women are always put first”;[112] consider also his radically feminist view of marriage in an 1845 letter to Edward Lott,[113] together with his repudiation of it in his Autobiography, in a passage written around 1894.[114]

On the question of a conservative turn on issues of class politics, the 19th-century individualist anarchist Benjamin Tucker, wrote in his journal, Liberty:

Liberty welcomes and criticises in the same breath the series of papers by Herbert Spencer on The New Toryism, The Coming Slavery, The Sins of Legislators, etc., now running in the Popular Science Monthly and the English Contemporary Review. They are very true, very important, and very misleading. They are true for the most part in what they say, and false and misleading in what they fail to say. Mr. Spencer convicts legislators of undeniable and enormous sins in meddling with and curtailing and destroying the people’s rights. Their sins are sins of commission. But Mr. Spencer’s sin of omission is quite as grave. He is one of those persons who are making a wholesale onslaught on Socialism as the incarnation of the doctrine of State omnipotence carried to its highest power. And I am not sure that he is quite honest in this. I begin to be a little suspicious of him. It seems as if he had forgotten the teachings of his earlier writings, and had become a champion of the capitalistic class. It will be noticed that in these later articles, amid his multitudinous illustrations (of which he is as prodigal as ever) of the evils of legislation, he in every instance cites some law passed, ostensibly at least, to protect labor, alleviate suffering, or promote the people’s welfare. He demonstrates beyond dispute the lamentable failure in this direction. But never once does he call attention to the far more deadly and deep-seated evils growing out of the innumerable laws creating privilege and sustaining monopoly. You must not protect the weak against the strong, he seems to say, but freely supply all the weapons needed by the strong to oppress the weak. He is greatly shocked that the rich should be directly taxed to support the poor, but that the poor should be indirectly taxed and bled to make the rich richer does not outrage his delicate sensibilities in the least. Poverty is increased by the poor laws, says Mr. Spencer. Granted; but what about the rich laws that caused and still cause the poverty to which the poor laws add? That is by far the more important question; yet Mr. Spencer tries to blink it out of sight.[115]

Tucker is essentially accusing Spencer of what I’ve elsewhere called “right-conflationism”[116] and Kevin Carson calls “vulgar libertarianism” – namely, the tendency of many libertarians to “have trouble remembering, from one moment to the next, whether they’re defending actually existing capitalism or free market principles,” and thus to “grudgingly admit that the present system is not a free market, and that it includes a lot of state intervention on behalf of the rich,” only to “go right back to defending the wealth of existing corporations on the basis of ‘free market principles.’”[117]

At the same time, one can find quite unconservative viewpoints, including viewpoints favorable to the poor over the rich, in writings close to the end of Spencer’s life. Consider Spencer’s discussion of labour unions in his 1896 Principles of Sociology. After some boilerplate right-libertarian criticism of unions,[118] Spencer turns toward their defense:

Judging from their harsh and cruel conduct in the past, it is tolerably certain that employers are now prevented from doing unfair things which they would else do. Conscious that trade-unions are ever ready to act, they are more prompt to raise wages when trade is flourishing than they would otherwise be; and when there come times of depression, they lower wages only when they cannot otherwise carry on their businesses.Knowing the power which unions can exert, masters are led to treat the individual members of them with more respect than they would otherwise do: the status of the workman is almost necessarily raised. Moreover, having a strong motive for keeping on good terms with the union, a master is more likely than he would else be to study the general convenience of his men, and to carry on his works in ways conducive to their health.[119]

Spencer goes still farther. Noting that “the regulation of labour becomes less coercive as society assumes a higher type,” Spencer affirms that the “transition from the compulsory cooperation of militancy to the voluntary cooperation of industrialism” will not be complete until the wage system is replaced by “self-governing combinations of workers.”

A wage-earner, while he voluntarily agrees to give so many hours work for so much pay, does not, during performance of his work, act in a purely voluntary way: he is coerced by the consciousness that discharge will follow if he idles, and is sometimes more manifestly coerced by an overlooker. ... So long as the worker remains a wage-earner, the marks of status do not wholly disappear. For so many hours daily he makes over his faculties to a master, or to a cooperative group, and is for the time owned by him or it. He is temporarily in the position of a slave, and his overlooker stands in the position of a slave-driver. Further, a remnant of the régime of status is seen in the fact that he and other workers are placed in ranks, receiving different rates of pay.[120]

Spencer predicts that the “master-and-workmen type of industrial organization” will inevitably be outcompeted by the “cooperative type, so much more productive and costing so much less in superintendence.” This is very close to the position that John Stuart Mill eventually embraced under the possibly misleading label of “socialism.”[121] Throughout his career, then, we find passages that seem to confirm Tucker’s indictment mingled with passages that seem to contradict it.

Endnotes

[110.] Social Statics, ch. 16. </titles/273#lf0331_label_180>.

[111.] Herbert Spencer, The Principles of Ethics, introduction by Tibor R. Machan (Indianapolis, Ind.: Liberty Fund, 1978), vol. 2, IV.20. </titles/334#lf0155-02_label_077>

[112.] Herbert Spencer, “From Freedom to Bondage,” The Man Versus the State, with Six Essays. </titles/330#Spencer_0020_691>

[113.] Letter to Edward Lott, 18 March 1845. <https://praxeology.net/HS-LM.htm>

[114.] Herbert Spencer, An Autobiography by Herbert Spencer, Illustrated in Two Volumes, Vol. I (New York: D. Appleton and Company 1904), ch. 26. </titles/2321#Spencer_1500-01_795>

[115.] Benjamin R. Tucker, “The Sin of Herbert Spencer,” Liberty, May 17, 1884. <http://fair-use.org/benjamin-tucker/instead-of-a-book/the-sin-of-herbert-spencer>

[116.] Roderick T. Long, “The Conflation Trap,” Bleeding Heart Libertarians, 7 November 2012. <https://bleedingheartlibertarians.com/2012/11/the-conflation-trap>

[117.] Kevin A. Carson, Studies in Mutualist Political Economy (Booksurge, 2007), p. 142. <http://www.mutualist.org/sitebuildercontent/sitebuilderfiles/MPE.pdf>

[118.] On left-libertarian vs. right-libertarian views of unions, see Kevin A. Carson, Labor Struggle: A Free Market Model, Center for a Stateless Society Paper No. 10 (Third Quarter 2010). <https://c4ss.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/C4SS-Labor.pdf>

[119.] Herbert Spencer, The Principles of Sociology, in Three Volumes (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1898), Vol. 3, Bk. VIII, ch. 20. </titles/2633#Spencer_1650-03_1979>

[120.]Principles of Sociology, Vol. 3, Bk. VIII, ch. 21. </titles/2633#Spencer_1650-03_2041>

[121.] John Stuart Mill, Chapters on Socialism, in The Collected Works of John Stuart Mill, Volume V: Essays on Economics and Society, Part II, ed. John M. Robson (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1967). </titles/232#Mill_0223-05_1239>

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.