Liberty Matters

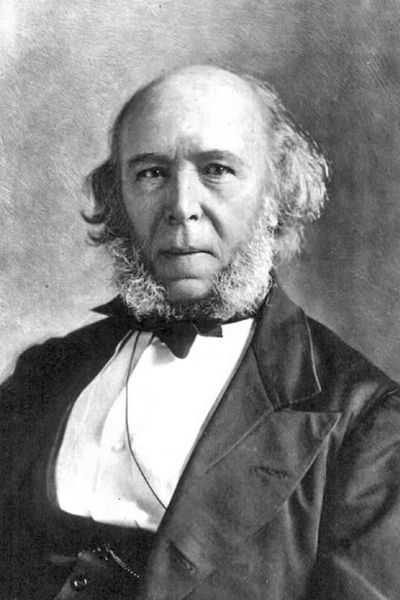

Did Herbert Spencer Misrepresent Benthamite Utilitarianism?

At the time he wrote Social Statics, Herbert Spencer had read virtually nothing in the fields of ethics and political philosophy. As he recalled late in life:

At the time Social Statics was written I knew of Paley nothing more than that he enunciated the doctrine of expediency; and of Bentham I knew only that he was the promulgator of the Greatest Happiness principle. The doctrines of other ethical writers referred to were known by me only through references to them here and there met with. I never then looked into any of their books; and, moreover, I have never since looked into any of their books.[62]

Shortly after Social Statics was published in December 1850, Spencer became friends with George Lewes and read his Biographical History of Philosophy, a popular work originally published in four volumes (1845-46). This became the major source for Spencer’s knowledge of the history of philosophy. In 1852, Spencer read J.S. Mill’s Logic, after George Eliot (Marian Evans) gave him a copy as a gift. “Since those days I have done nothing worth mentioning to fill up the deficiencies.” He tried several times to read Plato’s Dialogues but “quickly put them down with more or less irritation. And of Aristotle I knew even less than of Plato.”[63] As Spencer explained to Leslie Stephen:

If you ask how there comes such an amount of incorporated fact as is found in Social Statics, my reply is that when preparing to write it I read up in those directions in which I expected to find materials for generalization. I did not trouble myself with the generalizations of others.And that indeed indicates my general attitude. All along I have looked at things through my own eyes and not through the eyes of others.[64]

In The Data of Ethics (1879), which would become Part I of The Principles of Ethics, Spencer quoted from Bentham’s Constitutional Code, as well as from Plato’s Republic and Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics.[65] In view of Spencer’s disinterest in reading these and other quoted sources first-hand, it seems likely that the passages were located by Spencer’s research assistants, who also played an indispensable role in locating the thousands of examples and sources given in The Principles of Sociology.

Henry Sidgwick—Spencer’s most formidable critic, who wrote Outlines of the History of Ethics, The Methods of Ethics, and other important works—repeatedly accused Spencer of misrepresenting the views of Bentham and other utilitarians. For example, Sidgwick called Spencer’s attempt (in The Principles of Ethics) to link Jeremy Bentham to unqualified altruism “the most grotesque man of straw that a philosopher ever set up in order to knock it down.”[66] And in “Mr. Spencer’s Ethical System” (1880), Sidgwick considered Spencer’s conclusion that (in Spencer’s words) “general happiness is to be achieved mainly through the adequate pursuit of self-interest by individuals.” Sidgwick protested that this “was precisely Bentham’s conclusion. I think therefore that Mr. Spencer’s apparent antagonism to the Utilitarian school, so far as the ultimate end and standard of morality is concerned, depends on a mere misunderstanding.”[67]

Was Sidgwick correct? Did Spencer misrepresent Bentham in his attack on “empirical utilitarianism”? If so, may we attribute Spencer’s lack of understanding to his refusal to read original sources with any care?

I do not propose to address these questions here, except to note that I think Sidgwick overplayed his hand. Rather, I raise these questions as possible topics that the commentators may wish to address.

Endnotes

[62.] Letter to Leslie Stephen (2 July 1899), in David Duncan, Life and Letters of Herbert Spencer (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1908), II:146.

[63.] Ibid., II:147.

[64.] Ibid.

[65.] See The Principles of Ethics (New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1895), I:163

[66.] Henry Sidgwick, Lectures on the Ethics of T.H. Green, Mr. Herbert Spencer, and J. Martineau (London: Macmillan and Co., 1902), 184-85.

[67.] Henry Sidgwick, “Mr. Spencer’s Ethical System,” Mind, vol. 5 (1880), 221. A facsimile reprint of this article is contained in Herbert Spencer: Contemporary Assessments,” ed. Michael W. Taylor. This is part of the 12-volume edition of Herbert Spencer: Collected Writings, ed. Michael W. Taylor (London: Routledge/Thoemmes Press, 1996). For Spencer’s criticisms of Sidgwick, see Principles of Ethics, I:150 ff.; and “Appendix E,” II:461 ff.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.