Liberty Matters

Mitigating the Deficiencies of Democracy

I agree completely with Ioannis Evrigenis that Thucydides, Plato, and Aristotle have much to teach us about democracy. Some modern scholars have been so indignant that these ancient aristocrats dared to criticize democracy that they have sacrificed the golden opportunity of gleaning from their shrewd analyses its real deficiencies (every human system possesses deficiencies because humans are deficient), knowledge that is crucial to its preservation. Thucydides did not invent the fact that Alcibiades goaded the Athenian popular assembly into launching a disastrous military campaign in Sicily. Nor did Xenophon invent the fact that the assembly also approved the unjust execution of six of the city’s best generals, thereby precipitating the fatal defeat at Aegospotami soon after. Majority irrationality and tyranny are not figments of aristocratic imaginations. They are real phenomena that must be accounted for, not ignored because they are embarrassing. The romanticizers of democracy do it no favors. Rather, we should join Winston Churchill in saying that democracy is the worst form of government except for all others. Acknowledging the dark side of human nature and thus the impossibility of utopia allows for an adult conversation about mitigating democracy’s inherent deficiencies.

As Marco Romani observes, the proper education of citizens is a crucial element of mitigation. This is why Thomas Jefferson worked his whole adult life to introduce a system of public education in Virginia. Although he largely failed, he did play a leading role in the establishment of the University of Virginia, an accomplishment of which he was so proud that he instructed it be engraved on his tombstone, along with references to the Declaration of Independence and the Statute of Religious Freedom.

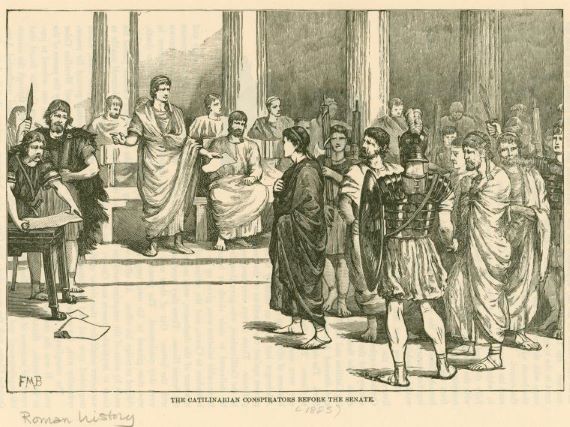

Finally, I agree with Charlotte Thomas that before we can have a meaningful discussion about republicanism and democracy, we must define these terms. But I disagree with the contention that we cannot know what the founders thought about them. Fortunately, they left behind a plethora of documents (letters, diary entries, speeches, and essays) that detailed their political philosophies. What we discover from this treasure trove is that they disagreed with one another. During the Revolution, they papered over their differences for the sake of unity, but these disagreements burst to the fore during the early republican period, leading to the rise of political parties. The sincere fervor with which Federalists and Democratic-Republicans denounced one another as traitors to republicanism (Caesars and Catilines, in the vernacular of the day) reflected astonishment and horror at the discovery that their opponents, whom they had recently considered brothers in arms, had not meant the same thing by the revered term “republic” as they meant.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.