Liberty Matters

Lincoln, Douglass, and Slavery

According to Abraham Lincoln, claims Peter Myers, the only Union worth preserving would be one in which slavery was on a path to its "ultimate extinction." This of course was a major rationale for the Free Soil Party. If slavery could be prevented from expanding it would eventually die of its own accord. (The other major rationale of Free-Soilism was the hope that non-extension would keep blacks out of the territories and future states. This is why Garrison attacked the Free Soil Party as the "white manism" party.) I believe that the belief in the natural extinction of slavery was a pleasant myth, one dissected as early as 1776 by Adam Smith in The Wealth of Nations. It was a myth that soothed the consciences of many antislavery politicians who did not want to risk their political careers by embracing abolitionism.

But let's put these theoretical conjectures aside and focus on what Lincoln had to say on this controversy. True, as a gradualist, Lincoln truly believed that slavery would eventually die a natural death (especially if encouraged by compensation to slaveholders), but in one of his debates with Stephen Douglas (1858) he speculated that this process might take as long as 100 years. The fact that, according to this prediction, slavery would have existed in the United States until 1958 didn't seem to bother the Great Emancipator, so long as slavery was on the path to extinction. I doubt if the 100-year timeline provided much comfort to those living slaves who were to endure their oppression for the rest of their lives.

There were many differences between abolitionists and gradualists (including Lincoln), but it is important to understand the fundamental point of contention. As William Lloyd Garrison put it in 1860, abolitionists were united in the belief that "the right of the slave to himself [is] paramount to every other claim."[92] In other words, it was not antislavery beliefs per se that were critical here, but the priority that an opponent of slavery gave to emancipation over other considerations. No person had the right to say to a slave, in effect: "Yes, slavery is a monstrous injustice, and you should be free. But to free you immediately would cause various social, economic, and political problems that we, the white folks, are unwilling to endure. So you will remain a slave until we deem it convenient to liberate you."

Although my characterization is a bit sarcastic, it accurately represents the arguments of gradualists. The gradualist Lincoln was no exception. He protested (before the Civil War) that the crusade for immediate emancipation endangered the Union and that without the Union the liberty of everyone would be in jeopardy. The slaves would therefore have to live in brutal oppression indefinitely for the sake of a greater good, until white folks decided that the time was right for them to live as free human beings. The abolitionists saw red when confronted with this kind of argument. For them freedom is a natural right that should be immune to cynical social and political calculations.

Myers correctly observes that many antislavery quotations from Lincoln are available. But these remarks tend to be very general and could have come from thousands of Americans. Things could get ugly, however, when Lincoln descended to particulars, as we see in this passage from the Lincoln-Douglas debates:

I will say then that I am not, nor ever have been in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races,—that I am not nor ever have been in favor of making voters or jurors of negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people; and I will say in addition to this that there is a physical difference between the white and black races which I believe will for ever forbid the two races living together on terms of social and political equality.[93]

These remarks could not be clearer, but in some hagiographical accounts of Lincoln, no effort is spared to explain them (and similar comments) away. Lincoln's view of slavery and civil rights evolved over time, we are told—though I know of no evidence that Lincoln changed his beliefs between 1858 and his inauguration as president in 1861. Or perhaps Lincoln softened his views on equal rights during the debates because he did not wish to alienate Illinois voters. Or, to speak more plainly, maybe Lincoln lied for the sake of gaining political power. But I take Lincoln at his word, even if his words take him out the running as one of the great champions of human rights during the 19th century.

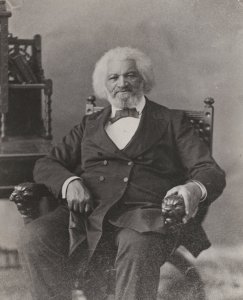

At one point Myers (as I understand him) suggests that the major difference between Lincoln and Frederick Douglass was between principle and prudence. Lincoln, savvier than Douglass, understood that to wage a civil war for abolition would be a bust. It would almost certainly have lost the border slave states to the Confederacy, and many northerners would not have fought to end slavery—so Lincoln prudently omitted slavery from his rationale for war.

There is no evidence to support this interpretation. Lincoln stated many times that his primary purpose in waging war was to save the Union, not to end slavery. One of his most unambiguous statements appeared in a response to Horace Greeley, who had criticized Lincoln for failing to make the Civil War a war for abolition. Lincoln replied, in part:

My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and it is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that. What I do about slavery and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save the Union; and what I forbear, I forbear because I do not believe it would help to save the Union.[94]

Lincoln, with his dedication to Whig principles, was an extreme nationalist who prized the preservation of the Union above every other political goal, including the abolition of slavery. Douglass and other abolitionists understood that Lincoln engaged in war with no intention of eradicating slavery, but they hoped that a policy of emancipation would be forced upon him as a necessary war measure, which is indeed what happened. (A common argument was that slave owners would need to devote more manpower to guarding their plantations if the slaves knew that they could escape to freedom.) Even after the Emancipation Proclamation (Jan. 1, 1863), Douglass could barely conceal his disgust at Lincoln's lack of "moral feeling." After praising the Emancipation Proclamation as a "vast and glorious step in the right direction," Douglass went on to say:

Our chief danger lies in the absence of all moral feelings in the utterances of our rulers. In his letter to Mr. Greeley the President told the country virtually that the abolition or non-abolition of Slavery was a matter of indifference to him. He would save the Union with Slavery or without Slavery. In his last Message he shows the same moral indifference, by saying as he does say that he had hoped that the Rebellion could be put down without the abolition of slavery.When the late Stephen A. Douglas uttered the sentiment that he did not care whether Slavery were voted up or voted down in the Territories, we thought him lost to all genuine feeling on the subject, and no man more than Mr. Lincoln denounced that sentiment as unworthy of the lips of any American statesman. But today, after nearly three years of a Slaveholding Rebellion, we find Mr. Lincoln uttering substantially the same heartless sentiments.[95]

In my opinion, even more serious was Lincoln's willingness to sacrifice 620,000 American lives in a bloody war for the sake of preserving the Union. There was nothing "irrepressible" about that conflict, and the world would not have imploded if the Confederacy had been permitted to secede in peace. Historians commonly mention Lincoln's admiration of the Declaration of Independence, but Lincoln seems to have overlooked the fact that Jefferson expressly wrote the Declaration as a defense of the right of secession. Lincoln, in stark contrast, denounced the right of secession as the "essence of anarchy." Lysander Spooner was among the very few abolitionists who understood the crucial difference between the evil of slavery and the right of secession, and who therefore defended the South's right to secede. Lincoln trails far behind Spooner and other abolitionists as a leading defender of natural rights in the 19th century.

Endnotes

[92.] William Lloyd Garrison, The Infidelity of Abolitionism (New York: American Anti-Slavery Society, 1860), in The Antislavery Argument, ed. William and Jane Pease (Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill, 1965), 129.

[93.] Quoted in Eric Foner, The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2010), 107.

[94.] Quoted in David Herbert Donald, Lincoln (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995), 368.

[95.] "The Mission of the War" (December 1863), in Frederick Douglass: Selected Speeches and Writings, ed. Philip S. Foner, abridged by Yuval Taylor (Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 1999), 560.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.