Liberty Matters

Frederick Douglass on the Right and Duty to Resist

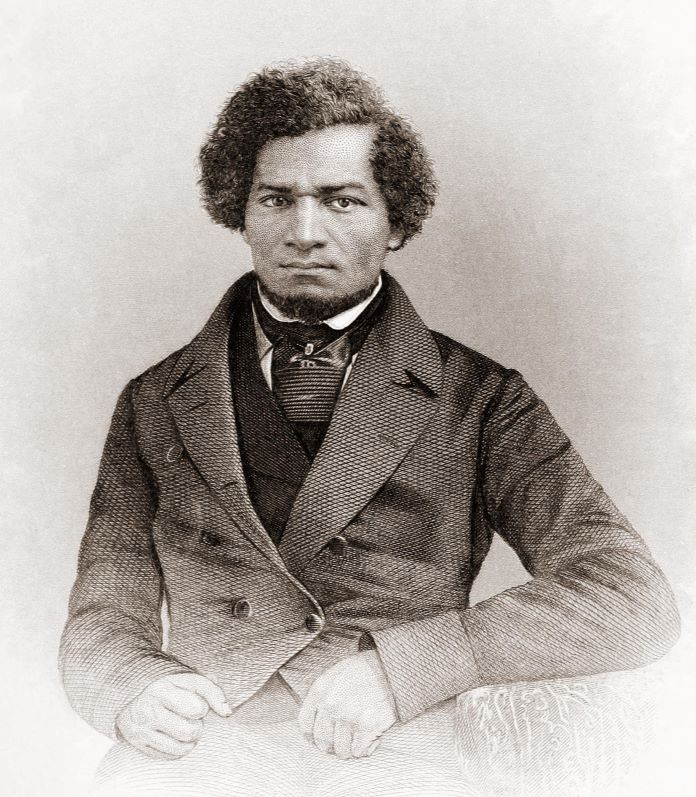

I am grateful to Helen Knowles, Peter Myers, and George Smith for their thoughtful commentaries. Their thoughts have inspired me to use this rejoinder to offer some reflections on how Douglass might help us make sense of prudence, which Aquinas defined as “right reason with respect to action” and contemporary political theorist Ethan Fishman identified as a virtue with a unique value for politics because of “its ability to explain how to realize abstract ends through concrete means available to human beings so that we may do the right thing to the right person at the right time for the right motive and in the right way.”[39]

Before we get to the matter of what it is prudent to do in order vindicate natural rights, let us consider whether or not there is any duty to do so in the first place.[40] There is a definite difference between Smith’s view – that there is no “duty, whether imperfect or perfect, to defend the rights of other people” – and Douglass’s view, which holds that our understanding of justice would be incomplete if it did not entail some consideration of what duties we have to others beyond the duty to respect their natural rights. The question that Douglass might ask Smith is this: have I fulfilled the duties entailed in natural rights if I refrain from violating the natural rights of others? Do I have an obligation to do anything (or refrain from doing particular things) in order to vindicate the natural rights of others (e.g., vote in particular ways, not vote in particular ways, not vote at all, obey particular laws, not obey certain laws, persuade people in particular ways, etc.)? It seems to me that Douglass’s general answer to that question was an emphatic yes. We do have a general duty to act in ways that, in our best judgment, will move us closer to realizing justice. [41] As we try to figure out precisely what acting on this duty looks like in the real world, prudence is the virtue that ought to guide us.

The Myers and Knowles essays invite us to bring these abstract questions of moral philosophy down to the ground of real politics. First, let us consider the relationship between prudence and the rule of law. As Myers points out, “The natural-rights doctrine at once requires and endangers the rule of law,” an institution that is supposed to secure our rights, but the natural-rights idea provides us with a “higher law” lens through which to challenge its very legitimacy. This is a tension, Knowles shows, that occupied Douglass’s mind for many years. Knowles describes Douglass’s move from a “Garrisonian” reading of the Constitution to a “Spoonerian” reading of the Constitution as one that captures his “principled pragmatism” (a.k.a. prudence). I think Knowles is right about this. Douglass thought long and hard about embracing this reading, and there are good reasons to believe that his change of mind had its roots in both pragmatism and principle. Pragmatically, Douglass was looking for additional tools beyond Garrison-style moral suasion to combat “the slave power.” Acceptance of the Constitution’s legitimacy would make available political tools that the Garrisonians refused to use. As a matter of principle, Douglass’s primary concern was with natural rights, and so long as he did not violate “good morality” in adopting antislavery constitutionalism, he thought it was prudent to do so.[42]

But Douglass’s ideas on the Fugitive Slave Act and John Brown reveal that his understanding of “good morality” permitted not only disobedience to unjust laws, but active resistance to them. This raises another crucial question: when is it prudent to use violence to vindicate natural rights? Myers’s framing of this question fits well with Knowles’s emphasis on the status of law in Douglass’s prudence: “were [the acts of resistance Douglass recommended],” Myers asks, “well conceived to correct the particular rights-violations at issue without doing intolerable harm to the rule of law?” In Myers’s estimation, Douglass got it right in the Burns case and wrong in the Brown case.

I am inclined to agree that Douglass got it right in the Burns case. As Myers indicates, the cause of liberating Burns was clearly just from a natural-rights perspective. What I find interesting, though, is the daylight between Myers’s justification and Douglass’s. For Myers, the prudence of the act of resistance in the Burns case turns on whether or not such acts pose a “serious danger to the rule of law or the stability of constitutional government.” While I do not think such concerns were irrelevant for Douglass, it is fair to say that before the Civil War, they were not as important to him as they are for Myers (or were for Lincoln.) Suppose resistance to the Fugitive Slave Act was widespread enough that it did pose a serious danger to the rule of law. I am not sure that would have led Douglass to change his view. For Douglass, the prudence of killing kidnappers did not turn on the danger such activity posed to the rule of law; it turned on the question of whether or not the activity would have the direct effect of vindicating the natural rights of fugitives and the indirect effect of deterring would-be kidnappers in the future. In sum, I think Myers is right to say that Douglass’s judgment in the Burns case is consistent with a defensible understanding of prudence, but I do not think the reasons Myers offers for this judgment are identical to Douglass’s reasons, and there may be something worth discussing in that difference.

Finally, there is the thorny case of John Brown. In their essays, both Knowles and Myers draw our attention to the issue of time. As time passed, Knowles reminds us, Douglass’s judgment of how best to realize his principles in the world changed. As he described so beautifully and hauntingly in the “Prospect in the Future” piece I cited in my lead essay, repeated appeals to the hearts, minds, and souls of the American people had failed to move them from “the downy seat of inaction.” What had long seemed to Douglass to be an imprudent course – an uprising of the slaves against their masters – now seemed, in his judgment, to be a course worth endorsing. Douglass viewed Brown as a kind of moral prophet because he realized – far sooner than most other abolitionists (including Douglass himself) – that reason, morality, art, and religion would not – indeed could not – bring about an end to slavery because it was a system of lawless violence that could only be “met with its own weapons.”[43]

As Knowles points out, it makes sense that the passing of time without abolitionist progress made Douglass more “militant,” but this does not necessarily undermine one crucial aspect of Myers’s critique: “the question … of timing.” Had Brown succeeded in his goal of starting an “abolition war” in 1859, Myers argues, the result likely would have been a “disaster for the antislavery cause.” As a historical matter, it seems likely that Myers is right about this. As a matter of principle, though, I am not ready to follow Myers in concluding that Douglass’s “overestimation of Brown’s virtue” constitutes a “significant failure of prudence.” My reluctance has to do with yet another way to think about the relevance of time to our judgment of this matter. Knowing what we know now, it seems easy to question the wisdom of Brown’s radical resistance, but I think Douglass was right to be reticent to pass such judgment on Brown. When he reflected on Brown’s activity, he was always careful to do so from the standpoint of the 1850s, not the 1860s, 1870s, or later. From the perspective of 1859 – when Brown had good reason to feel a sense of “weary hopelessness” about the prospects for abolition – was it really imprudent to take radical action? As a tactical matter, the answer is clearly yes (and Douglass thought so at the time.) But as a matter of natural-rights morality in that moment in time, I am not so sure we can conclude that Brown’s actions – or Douglass’s defense of them – were imprudent. Prudence is the virtue that helps us figure out what means we ought to use in order to realize our principles in the world. We ought to judge the prudence of others based on the range of options available to them at the time of decision, not from a God-like position from which we have a universe of options available to us. In 1859, what means seemed viable to radical abolitionists like Douglass and Brown? After the many setbacks of the 1850s, was it prudent any longer to rely solely on appeals to “the higher and better elements of human nature?”[44] These are tough questions, and I am therefore less than convinced that Douglass’s judgment of Brown’s character constitutes a failure of his prudence. I am so grateful to these distinguished scholars for pushing me to think more deeply about these matters, and I look forward to our conversation.

Endnotes

[39.] Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, (IIaIIae, 47.2) and (IIaIIae47.4). Ethan Fishman, “Introduction,” Tempered Strength: Studies in the Nature and Scope of Prudential Leadership (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2002), 5.

[40.] I accept Smith’s criticisms of my use of the term “imperfect duty." I knew I was stepping onto treacherous terrain when I attempted to apply a formal philosophical concept to Douglass, who Smith is right to say was not driven primarily by a desire to articulate “fine points of political theory.” In conceding this point, I do not mean to – nor do I think Smith means to – slight Douglass. As I’ve argued elsewhere, Douglass’s primary concern was with political action that would bring us closer to justice. He pursued such action in a thoughtful and reflective way and took ideas very seriously. He was not, though, a philosopher and I think he is better understood as a philosophical reformer-statesman.

[41.] I am not sure about exactly what philosophical terminology to use to describe Douglass’s position, but I am inclined to think he is right. Indeed, I have struggled to find a good name for this idea for well over a decade of work on Douglass. If you have any ideas, please do let me know.

[42.] Letter from Douglass to Gerrit Smith, January 21, 1851, in Philip Foner, ed. Selected Speeches and Writings, 171.

[43.] Frederick Douglass, “Captain John Brown Not Insane,” in Philip Foner, ed. Selected Speeches and Writings, 375.

[44.] Frederick Douglass, “The Prospect in the Future,” in The Essential Douglass, 137.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.