Liberty Matters

The Secret Prehistory of Equality

The Essays of Michel de Montaigne are indeed among the formative cultural monuments of the Western world, as Stuart Warner reminds us. Nor is it at all impossible that they contain the artful juxtapositions, allusions, and hidden messages hinted at by Stuart’s post. There was no subtler chronicler and practitioner of the arts of the genuinely free mind than he. That is one reason they were indeed read by just about everyone in the period we are discussing. And unlike some of the classics of that period, such as Erasmus’s In Praise of Folly to take one example, which may have lost some of its lustrous topicality in the five centuries since its publication, the engaging genius and irrepressible individuality of Montaigne’s voice resonates just as forcefully for us today as if we were sitting with him in his Bordeaux tower.

But if the question before the house concerns the secret prehistory of equality, as Stuart’s most intriguing remarks seem to suggest, then allow me to point toward another avenue into the subject, one that I hope to trace back to the beginning of our discussion. If Stuart Warner is right, as I believe he is, in his apparent suggestion that “equality” is a value that doesn’t just “happen” of its own accord but that needs to be developed and articulated by our cultural and intellectual leaders, and if Montaigne was indeed one of those leading cultural innovators as Stuart and I both agree, it is also true that as I hinted at the end of my original post, things were happening at the level of practice that made the value of “equality” a more live possibility than might otherwise have been the case--especially “equality” between the sexes.

The Hollywood news media narrative of a world groaning under The Patriarchy until the Suffragettes or Betty Friedan and Gloria Steinem hoisted it on their heroic shoulders is about as far removed from reality as a myth is capable of straying. Bernard Lewis is much closer to the truth when he observes that 600 years ago already, “Western civilization was richer for women’s presence; Muslim civilization, poorer by their absence.”[113] Lewis himself was referring to the relative prevalence of monogamy in the West, by comparison with the polygamy and legalized concubinage so much in evidence elsewhere. But in recent decades, this picture of Western exceptionalism has been deepened and fleshed out considerably, both from within Europe and beyond, while the dynamics of its genesis and its unfolding remain frustratingly murky.

From within Europe, the European Marriage Pattern I mentioned the other day has been summarized as including the following key elements: delayed marriage and relatively similar average ages of marriage for the two sexes, high rates of voluntary celibacy and correspondingly low crude birth rates, more young women as well as men in the workforce accumulating property, with corresponding effects on the nature of the relationship between spouses after marriage, and between parents and children.[114] Outside of Europe, Western commentators are again relearning just how deeply the differences between the West and the Rest in their respective treatments of women can go in explaining problems of economic and political development.[115] While no one would suggest that life for women (and men) hovering near the Malthusian Trap before the Industrial Revolution was anything other than very hard, and far from equal, there was nonetheless scope for a certain kind of personal initiative, even a certain kind individual liberty among them that many women elsewhere could only dream about. “Though wedlock I do not decry,” wrote the Flemish poet Anna Bijns, Montaigne’s near contemporary, “Unyoked is best! happy the woman without a man.”[116]

Perhaps this deeper pattern of customs, traditions, and relationships helps explain another odd shard of sexual equality (or at least “equality”) in the age of the Renaissance. If the ambiance of Plato’s Academy and Aristotle’s Lyceum was emphatically a man’s world, the flavor of intellectual life by Montaigne’s time was markedly different. In his delightfully conceived Women in the Academy,[117] C.D.C. Reeve imagines the conversations that might have occurred in Plato’s grove when two women--Axiothea of Phlius (who dressed like a man) and Lasthenia of Mantinea--showed up to pursue philosophy. By Montaigne’s time, of course, people no longer had to imagine, for Castiglione had made the image real.

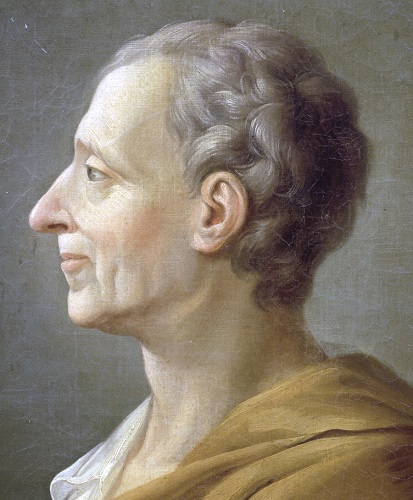

As I’m sure Stuart Warner will agree, the 1524 work The Book of the Courtier had a trajectory in the cultural history of Europe that was nearly as remarkable as that of Montaigne himself. Its success must surely say something about the underlying attractiveness even at that early date of a group of cultured, elite men and women engaging in conversation about some of the big conceptual issues on their minds. Roughly speaking, this was the sort of world--a world not of equality in any democratic sense but of certain “equalities” nonetheless--that produced a Nicolosa Sanuti and emboldened her to speak up. As such, we can say that this world also helped make the breezy quotidian repressions embedded in the whole sumptuary law regime an item for legitimate discussion. I will only conclude with this irony: Montesquieu, who as a denizen of the salons of Paris and especially of his friend the Marquise of Lambert was quite familiar with the ambiance captured in Il Cortegiano, offered a less robust solution to Sanuti’s problem than did the socially awkward bachelor Adam Smith.

Endnotes

[113.] Bernard Lewis, Cultures in Conflict: Christians, Muslims, and Jews, in the Age of Discovery (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), p. 24.

[114.] See Jack Goody, The development of the family and marriage in Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), p. 8.

[115.] For recent examples, see Gary A. Haugen and Victor Boutros, The Locust Effect: Why the End of Poverty Requires the End of Violence (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014); Nicholas D. Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn, Half the Sky: Turning Oppression into Opportunity for Women Worldwide (New York: Vintage Books, 2009); Anke Hoeffler and James Fearon estimate (controversially) that violence in the home, largely against women, is a far more expensive and serious impediment to economic development than homicide, terrorism, or civil war. See their “Conflict and Violence” Assessment Paper for the Copenhagen Consensus Center, http://www.copenhagenconsensus.com/sites/default/files/conflict_assessment_-_hoeffler_and_fearon_0.pdf

[116.] Cited in Tine de Moor and Jan Luiten van Zanden, “Girl Power: The European Marriage Pattern and Labour Markets in the North Sea Region in the Late Medieval and Early Modern Period,” Economic History Review 63, no. 1 (2010): 1-33, quote at 1.

[117.] C.D.C. Reeve, Women in the Academy (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Co., 2001).

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.