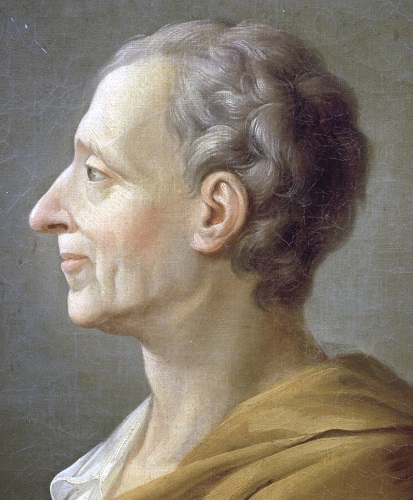

Liberty Matters

Montesquieu on Liberty and Sumptuary Law: A Rejoinder

Sincere thanks to my learned friends Paul A. Rahe, Stuart D. Warner, and David W. Carrithers--friends whose erudition has turned their “comments” on my original post into the start of veritable essays of their own.

Sincere thanks to my learned friends Paul A. Rahe, Stuart D. Warner, and David W. Carrithers--friends whose erudition has turned their “comments” on my original post into the start of veritable essays of their own.Paul Rahe makes the astute suggestion that at a certain point in The Spirit of the Laws, England replaces Athens as a model for commercial republicanism in Montesquieu’s schema, and in a fashion relevant to our own era. Noting Montesquieu’s warning (5.6) that an “excess of wealth” can “destroy the spirit of commerce,” Professor Rahe poses a timely question: “What happens when commercial society and the operations of the market have been so successful in promoting prosperity that they are no longer efficacious in producing the bourgeois virtues?”

It is certainly true that there is plenty of evidence around today to support the case--chronicled, for example, in works like Nick Eberstadt’s A Nation of Takers[57] --that the bourgeois virtues aren’t what they used to be. On the other hand, if Montesquieu thought that modern commercial societies such as the English lacked the benefit of sumptuary laws, he also seems to have believed they possessed other resources unavailable to the ancients. When his British friend William Domville asked about the prospects of England following the ancients down the path of corruption and collapse, he was circumspect, but cautiously optimistic, as Paul Rahe well knows.[58] English wealth, Montesquieu wrote, was different in origin from Roman wealth, arising as it did from commerce and industry rather than from conquest and fiscality. Instead of the growing polarization between haves and have-nots that he saw in late Rome, England had a robust middling class that was less corrupt than the classes above and below them, and thus less likely to foretell such a Roman-style collapse.[59] Were he alive today, when the middling class is vastly larger than it was in his own time, it strikes me as not impossible that Montesquieu would find more confirmation than disconfirmation in his original diagnosis.

Moreover, there is good reason why we students of the past are not much sought after for our predictive prowess. In the 1970s, the sociologist Daniel Bell addressed his own concerns about the vitality of the bourgeois virtues by cataloguing in compelling fashion what he came to see as the Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism.[60] If the trajectory of the Western world since then has been more up-and-down in nature than the linear descent that his brilliant analysis might have foretold, perhaps this is at least partly because there are hidden resources of self-correction in an open capitalist democracy--redolent of Montesquieu’s answer to Domville--that we tend to overlook. I tentatively conclude that the case for pessimism is strong and plausible, but as yet inconclusive.

Stuart Warner takes us on a wonderfully “roundabout” circuit through the landscape of liberty in Montesquieu’s thought. In doing so, he reminds us that The Spirit of the Laws was very carefully assembled, and that liberty became a central focus only in books 11 and 12. I welcome this reinforcement and elaboration of my theme, since my point of course had been to highlight how sumptuary law was not specifically analyzed for its liberty-friendliness in book seven. I also welcome Professor Warner’s insightful remark that it is not constitutional arrangements alone but “substantive laws” that define the true scope of liberty in Montesquieu’s theory, since I presented sumptuary legislation as precisely one of those “substantive laws” in which the stakes of liberty are decided.

But Professor Warner further takes us to the later books on commerce (books 20 and 21), an activity whose chief importance, he argues, is to bring with it manners that are “gentle” and even “feminized.” Montesquieu’s entire conception of liberty, he suggests, is crucially focused on the condition of women, which leads Professor Warner to regret (I think) that I had not spent more time in my discussion of sumptuary laws treating their relevance for the condition of women.

It is certainly true that Montesquieu uses the device of the harem to illustrate the relationship between liberty and despotism in the travels of Usbek and Rica in The Persian Letters, and that he returns to the trope of the domestic restraints on women as an illustration of the broader theme of despotism in later works and in his intellectual diary. Whether his evocation of “le doux commerce” in book 20 of The Spirit of the Laws means that commerce itself comes to us as a “feminized” activity is a separate (and quite intriguing) question. But in broad outline, I agree with Stuart Warner that a full essay on the place of women in Montesquieu’s view of the relationship between the three constitutional types, on the one hand, and the themes of both luxury and sumptuary laws, on the other, would indeed be a worthwhile endeavor, even if I did not engage in it myself. My chief reason for focusing on sumptuary law (aside from space limitations) was that it seemed to provide a convenient and mostly neglected vehicle for understanding the changing relationship between ruler and ruled--not only in Montesquieu’s thought but in Europe as a whole at the dawn of modernity.

And this brings me to Professor Carrithers. I had begun my post by noting that “[p]leasing God, controlling elites, keeping down the plebs, reining in women, protecting local interests, and enriching the state” were among the rationales used by governments for enacting sumptuary laws throughout Europe for many centuries. Drawing on his considerable fount of learning, David Carrithers mostly expands upon this observation by surveying some of the remarkably different agendas that European governments pursued when they called upon that old stand-by of social control, sumptuary law.

In that context, he takes up my puzzlement at their eventual disappearance. He correctly points out, citing Sarah Maza and Jeremy Jennings, that critics continued to outnumber defenders of luxury even by the late 18th century, often called the Age of Revolution. (It is less clear, of course, whether those critics “decisively out-argued” defenders, as Maza had suggested.) Professor Carrithers then proceeds to explore whether the key breakthrough occurred in the realm of economic theorizing or by some other route.

In particular, he notes two alternative, non-economic possibilities: first, he observes that the “record of enforcement was abysmal.” This was indeed mostly true in most parts of Europe, though not necessarily equally for all. Travelers were sometimes impressed with the putative success of sumptuary laws in places like Basel or Geneva.[61] In an area where perception counted for as much as reality, this perception (or misperception) was no doubt itself a factor in their surprising durability. More importantly, abysmal enforcement had prevailed for centuries before Montesquieu--a fact that had been noted by governments and governed alike. In light of the attraction of “successful” models of sumptuary law in places like Switzerland, it might be thought that England, which had mostly repealed its own by the beginning of the Stuart monarchy, would provide an effective counter-model by the 18th century. It sounds plausible, but I know of no evidence that any continental Europeans wanted to repeal their own sumptuary laws because they saw how successfully the English had done so.

The second non-economic possibility David Carrithers mentions is psychological rather than political in nature. Not unlike censorship, sumptuary law calls attention to something that might otherwise escape notice, and thereby unwittingly adds a cachet that it would not otherwise have had. The example Professor Carrithers cites, also noted by Professor Warner, is Montaigne. The great essayist’s ironic approach to sumptuary law, resting on the case of the ingenious Locrian ruler Zaleucus in the seventh century BC, was indeed cited several times in the following two centuries, but not nearly often enough or seriously enough, in my view, to account for the sea change that needs explaining.

I agree with David Carrithers that there is no obvious reason why the disappearance of sumptuary law should have been primarily economic in nature. Indeed, since no characteristically “economic” method of analysis emerged to prominence in Europe until about the middle of the 18th century, I think we could rather expect that such a change in mental orientation would have had roots that were as non-economic as they were economic in nature. But it also seems to me that the non-economic alternatives that he sensibly cites fall somewhat short of offering full explanations, and that a mystery of sorts therefore remains.

Endnotes

[57.] Nick Eberstadt, A Nation of Takers (Templeton Press, 2012).

[58.] For his summary of the episode, see Paul A. Rahe, Montesquieu and the Logic of Liberty (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 136-41.

[59.] See Montesquieu, My Thoughts, trans. and ed. Henry C. Clark (Indianapolis, IN: Liberty Fund, 2012), 1960, pp. 594-95. Online: </titles/2534#lf1609_label_2326>.

[60.] Daniel Bell, The Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism (New York: Basic Books, 1976).

[61.] For Basel, see Guillaume-Alexandre Méhégan, Tableau de l’histoire moderne (Paris: Saillant, 1766; trans. into English in 1779); William Coxe, Sketches of the Natural, Civil, and Political State of Swisserland (London: Dodsley, 1779), 97-98, 504-5, and Abbé de Mably, De l’étude de l’histoire, à Monsieur le Prince de Parme (Parma: Royal Printer, 1775), 4-7. For Geneva, there is of course the “citizen of Geneva” himself, Jean-Jacques Rousseau; a typical example can be found in his Politics and the Arts: Letter to d’Alembert on the Theatre, trans. Allan Bloom (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1960), 93.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.