Liberty Matters

Why Sumptuary Laws Endured

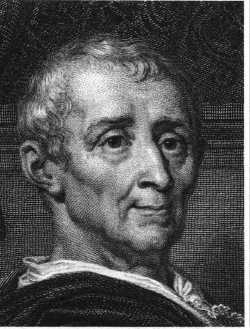

My previous posts mainly focused on why the impulse to pass sumptuary laws gradually weakened. Obviously, much more could be said on this topic, particularly regarding the influence of economic theory on Montesquieu and other leaders of European thought. Rather than continuing that line of investigation, however, I would like to reverse course and focus attention on why the urge to pass sumptuary laws lasted so long. And to assist with this analysis, I will draw upon the stellar work on Italian sumptuary legislation of Catherine Kovesi Killerby referenced by Hank Clark in his thought provoking initial essay.[84] Since space is limited, I will focus just on public-policy reasons for passing sumptuary laws regulating marriages and funerals, leaving aside the strong religious rationales operative in the minds of such papal legates as Cardinal Bessarion, whose sumptuary edict for Bologna in 1453 so infuriated Nicolosa Sanuti.

I’ll begin with the perceived need to regulate marriage. Since Italy experienced sharp population losses during the 14th and 15th centuries owing in part to the Black Death of 1348 and other epidemics,[85] encouraging marriage to boost population became a high concern of state. The costs associated with marriage were pricing prospective couples out of the market. By custom, brides needed trousseaus, and a growing appetite for luxury items was making them prohibitively expensive, so much so that the citizens of Lucca in 1380 asked the city government to restrict the items that could be included since many could not afford the “inordinate multitude of furs, ornaments, pearls, garlands, belts, and other expenses” that had become the fashion of the day.[86] The more expensive the trousseau, the less actual cash was left in the dowry since the value of the trousseau was subtracted from the total value of a woman’s dowry[87] One Ginevra Datini, for example, would have had a large dowry of 1,000 gold florins, “but her trousseau was so lavish that her husband was left with a mere 161 florins in cash.”[88]

Clearly there was an incentive for governments to intervene. Thus in Messina, as early as 1272, a sumptuary law sharply limited the amount of money that could be spent on dowries and trousseaus while also restricting the number of guests who could be invited and how much brides could spend on their wedding apparel.[89] Similar policies were adopted by many other governments. In Genoa, for example, beginning in 1449 the value of a bride’s trousseau could not exceed one-fifth the value of the dowry.[90] The rising costs of trousseaus was only part of the marriage problem. Wedding ceremonies had become inordinately expensive, and lawmakers acted to limit those costs. Thus governments in Italy, whether republican, monarchical, or despotic, passed laws limiting the number of attendants brides and grooms could have at their wedding and specifying how expensive the gifts for those attendants could be, how many guests could be invited to weddings, what could be served at the wedding banquets, and how much could be spent on wedding presents for the bride and groom.[91] Some governments were so focused on increasing population through marriage that they restricted eligibility for public office to those who were married and spent public money on marriage brokers.[92]

A concern for political stability also drove passage of sumptuary laws regarding marriage. Currents of dissent and bitter factionalism swirled just beneath the surface of Italian governments, and many sumptuary laws were designed to curb what Killerby has termed “the display of family strength, both in terms of wealth and numbers.” The goal, she says, was to prevent “unfocused political disaffection” from becoming “focused upon a particular person, family, or faction.”[93] Weddings, she explains, presented a prime opportunity for families to come together and gain allies, and therefore “the majority of wedding laws devoted most of their rubrics to limiting the numbers that could attend each of the stages of a new marriage alliance and specifying who was allowed to be included amongst the guests.”[94]

Funerals could also have political ramifications since the deceased might be clearly identified with some political cause or grievance. Excessive attention to the passing of a revered and politically influential person might unleash destructive impulses and factional strife. Thus sumptuary laws banned “excessive wailing, weeping, tearing of hair, and beating of palms, particularly by women.”[95] A statute passed in early 14th-century Modena forbade “anyone to cry loudly outside the house of the deceased or to beat the hands or palms.”[96] Some laws excluded women altogether from funeral processions since they were most likely to publicly display grief, and other laws allowed women to be part of the procession only if the deceased was a woman or a boy no older than 10 and thus not likely to become a rallying point for a faction.

Many governments imposed restrictions on who could wear mourning clothes and for how long, and laws were passed restricting the way corpses could be clothed (often just in plain wool lined with linen) not just to “prevent wasteful expenditure” but also because “to display wealth was also to incite ambition and display potential political power.”[97] Some sumptuary laws even banned all public officials from attending funerals in order “to prevent anyone with political power from identifying himself too closely with the interests of a specific individual or family.”[98] Other sumptuary laws, in Milan and Brescia for example, banned the display of any family banners that would augment the prestige of a particular family.[99]

Summing up the reason for passage of sumptuary laws regarding funerals, Killerby has said: “Presumably the reasoning here was that such open displays of grief would serve to arouse passions and unite mourners around a common cause, thereby serving the interest of the politically ambitious.”[100] So concerned were governments that funerals would ignite passions and form factions that the sumptuary laws governing them were exceptionally detailed. To take just one example, a Paduan law of 1398 stipulated that “no bells were to be rung without the permission of the consiglio del Signore; that only a single order of mendicants and the parishioners of the church in which the corpse was to be buried could follow the bier…; that no more than four torches were to be carried in the process, and each of these was not to weigh more than 4 lb; that only the inhabitants of the deceased’s house and his mother, sisters, and daughters could wear scarves (fazzoletti); and that no one was to dress in mourning except the wife and children of the deceased.”[101]

These very brief examples of perceived public needs can help us understand why the demise of sumptuary laws took place over the course of many centuries and was by no means preordained. It was clearly a combination of economic and noneconomic factors, along with changing conceptions of liberty (including liberty for females as per Sanuti’s protest) and the rise of free-market economic theory, that a full explanation must take into account. I once again thank Hank Clark for enabling us to embark on an intriguing discussion that, as he reminds us in the concluding sentence of his initial post, can serve to “remind us of what a mottled, murky landscape the history of liberty really is.”

Endnotes

[84.] Catherine Kovesi Killerby, Sumptuary Law in Italy, 1200-1500 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2002).

[85.] Ibid., 52-53.

[86.] Ibid., 51, citing S. Bongi, ed., Bandi lucchese del secolo decimoquarto: Tratti dai registri del R. Archivio di Stato in Lucca (Bologna, 1863), 311.

[87.] Ibid., 54-55.

[88.] Ibid., 55, citing I. Origo, The Merchant of Prato (London, 1984), 189

[89.] Ibid., 56-57.

[90.] Ibid., 57, citing Pandiani, 193.

[91.] Ibid., 58.

[92.] Ibid., 58.

[93.] Ibid., 66.

[94.] Ibid., 69.

[95.] Ibid., 72.

[96.] Ibid., 73, citing C. Campori, “Del governo a comune in Modena secondo gli statuti ed altri documenti sincroni,” in Statuta civitatis mutine, (Monumenti di storia patria delle provincie modenesi), Serie degli statuti, I (Parma, 1864), 474.

[97.] Ibid., 75-76.

[98.] Ibid., 76-77. Killerby also discusses restrictions on baptismal ceremonies similarly designed to lessen the likelihood of alliances between families being formed. (Ibid., 77)

[99.] Ibid., 77-78.

[100.] Ibid., 72

[101.] Killerby, 71, citing Bonardi, 11.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.