Tracts on Liberty by the Levellers and their Critics Vol. 8 Addendum (1638–1646)

1st Edition, uncorrected (Date added: August 4, 2015)

This volume is part of a set of 7 volumes of Leveller Tracts: Tracts on Liberty by the Levellers and their Critics (1638-1659), 7 vols. Edited by David M. Hart and Ross Kenyon (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2014). </titles/2595>.

It is an uncorrected HTML version which has been put online as a temporary measure until all the corrections have been made to the XML files which can be found [here](/titles/2595). The collection will contain over 250 pamphlets.

- Vol. 1 (1638-1843): 11 titles with 1,562 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-1>

- Vol. 2 (1644-1645): 12 titles with 564 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-2>

- Vol. 3 (1646): 22 titles with 854 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-3>

- Vol. 4 (1647): 18 titles with 2,011 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-4>

- Vol. 5 (1648): 30 titles with 1,078 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-5>

- Vol. 6 (1649): 27 titles with 277 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-6>

- Vol. 7 (1650-1660): 42 titles with 1,055 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-7>

- Addendum Vol. 8 (1638-1646): 33 titles with 1,858 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-8>

- Addendum Vol. 9 (1647-1649): 47 titles with 2,317 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-9>

To date, the following volumes have been corrected:

- Vol. 1 (1638-1643) </titles/2597>

- Vol. 2 (1644-1645) </titles/2598>

- Vol. 3 (1646) </titles/2596>

Further information about the collection can be found here:

- Introduction to the Collection

- Titles listed by Author

- Combined Table of Contents (by volume and year)

- Bibliography

- Groups: The Levellers

- Topic: the English Revolution

2nd Revised Edition

A second revised edition of the collection is planned after the conversion of the texts has been completed. It will include an image of the title page of the original pamphlet, its location, date, and id number in the Thomason Collection catalog, a brief bio of the author, and a brief description of the contents of the pamphlet. Also, the titles from the addendum volumes will be merged into their relevant volumes by date of publication.

Tracts on Liberty by the Levellers and their Critics, Volume 8 Addendum to (1638–1646)

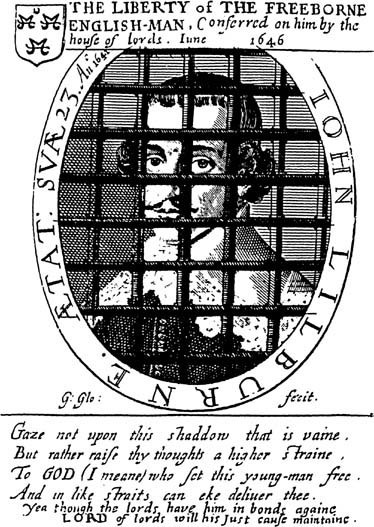

The Liberty of the Freeborne English-Man, Conferred on him by the house of lords. June 1646. John Lilburne. His age 23. Year 1641. Made by G. Glo.

“Gaze not upon this shaddow that is vaine,

Bur rather raise thy thoughts a higher straine,

To GOD (I meane) who set this young-man free,

And in like straits can eke thee.

Yea though the lords have him in bonds againe

LORD of lords will his just cause maintaine.”

Table of Contents

- Editor's Introduction

- Additional Tracts from 1638–1646 (Volume 8)

- 8.1. John Selden, A Brief Discourse concerning the Power of the Peeres (1640) [10 illegibles]

- 8.2. John Davies, An Answer to those Printed Papers by the late Patentees of Salt (1641) [1 illegible]

- 8.3. Anon., The Lamentable Complaints of Nick Froth the Tapster (May 1641)

- 8.4. Katherine Chidley, The Justification of the Independant Churches of Christ (October, 1641) [31 illegibles]

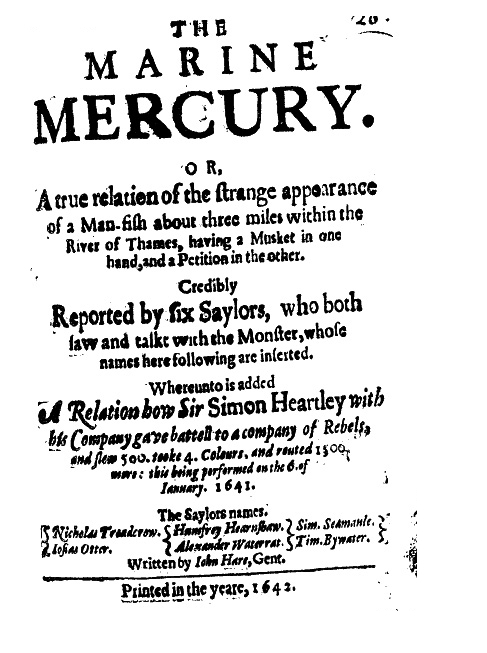

- 8.5. John Hare, The Marine Mercury (6 January, 1642)

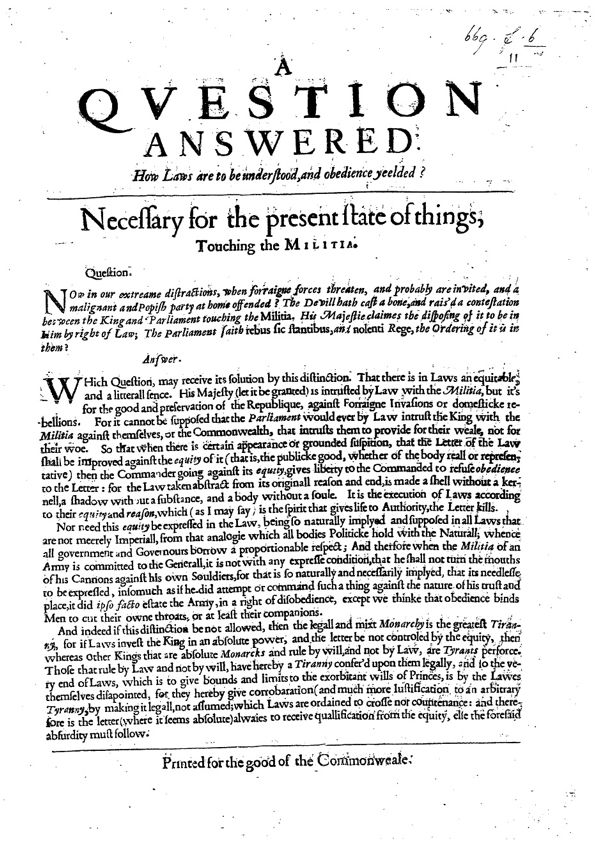

- 8.6. Anon., A Question Answered (21 April, 1642)

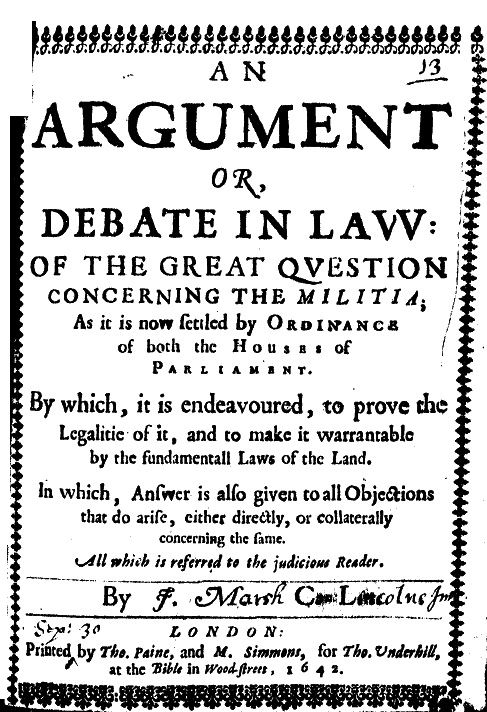

- 8.7. John Marsh, The Great Question concerning the Militia (30 September, 1642) [103 illegibles]

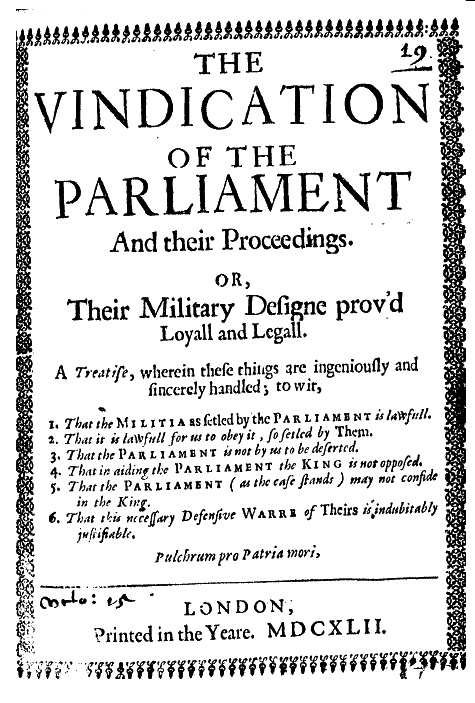

- 8.8. Richard Ward, The Vindication of the Parliament (15 October, 1642) [21 illegibles]

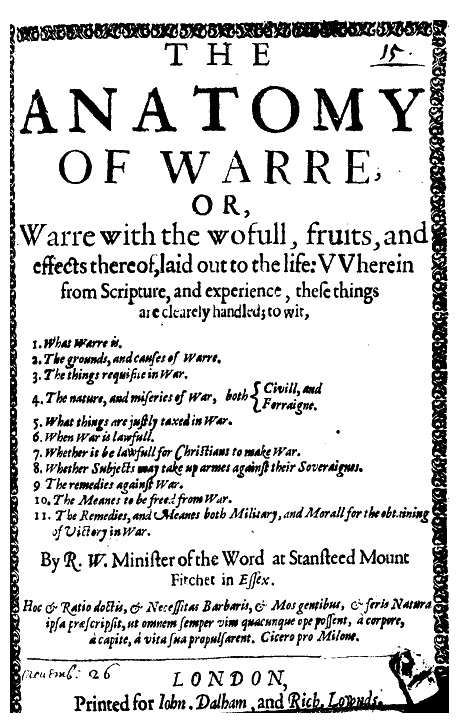

- 8.9. Richard Ward, The Anatomy of Warre (26 November, 1642) [110 illegibles]

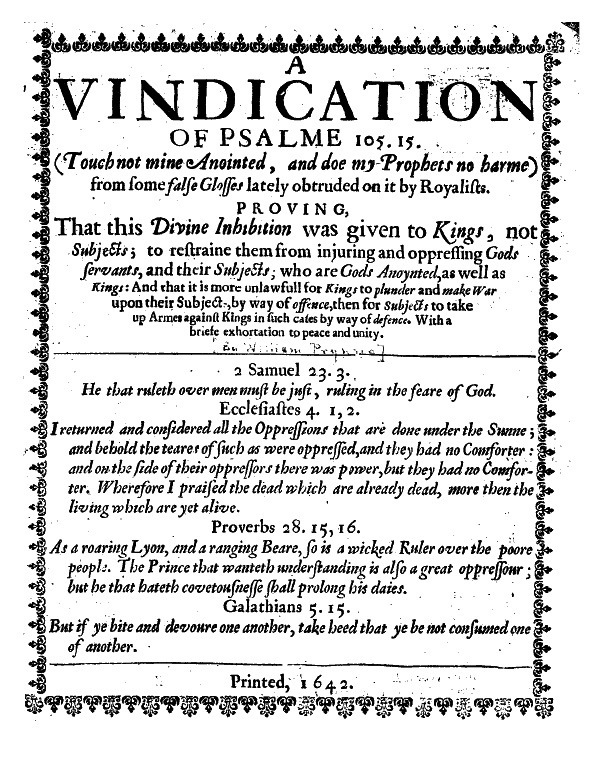

- 8.10. William Prynne, A Vindication of Psalme 105.15 (6 December, 1642) [31 illegibles]

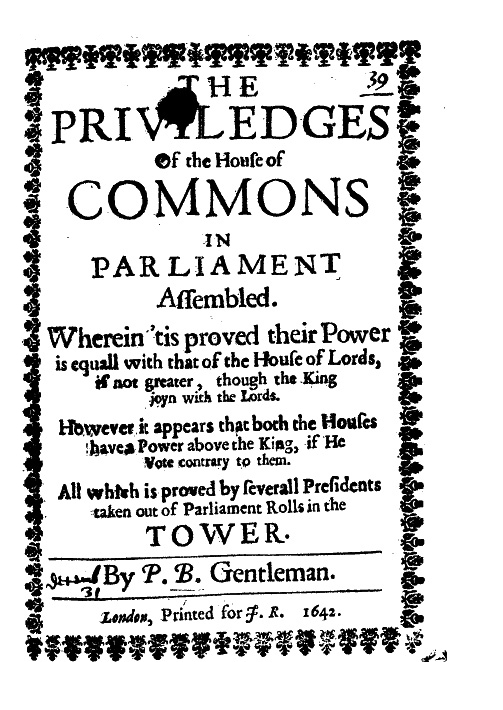

- 8.11. Anon., The Privileges of the House of Commons (31 December, 1642) [6 illegibles]

- 8.12. John Norton, The Miseries of War (17 January, 1643) [8 illegibles]

- 8.13. Anon., The Actors Remonstrance (24 January, 1643) [3 illegibles]

- 8.14. Anon., Touching the Fundamentall Lawes of this Kingdome (24 February, 1643) [31 illegibles]

- 8.15. Anon., Briefe Collections out of Magna Charta (19 May, 1643) [1 illegible]

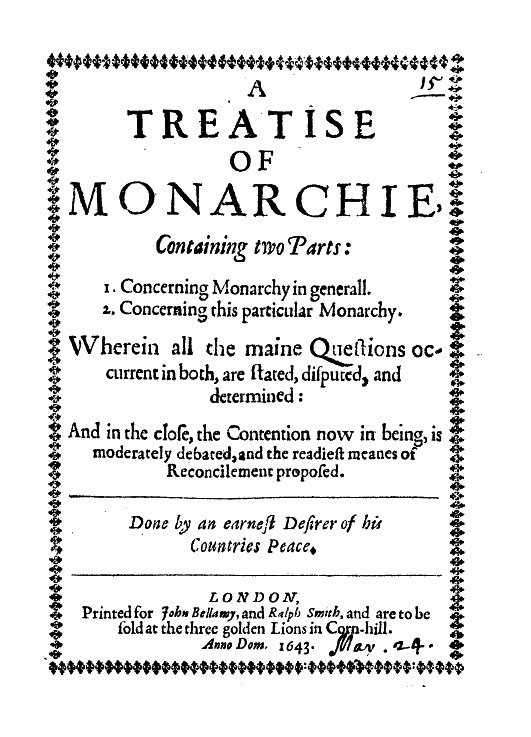

- 8.16. Philip Hunton, A Treatise of Monarchy (24 May, 1643) [42 illegibles]

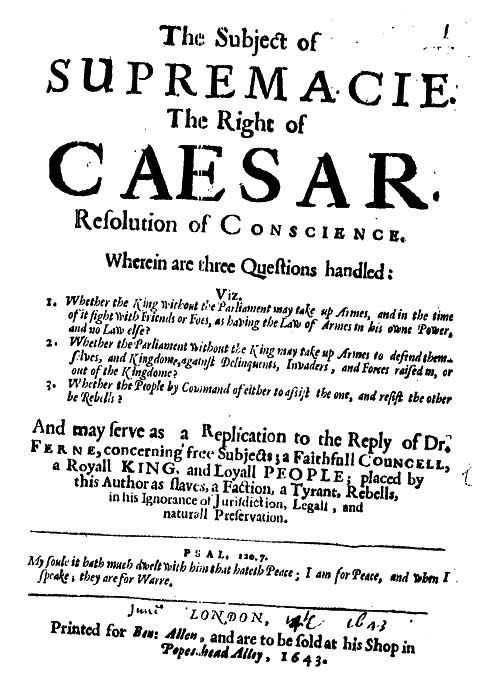

- 8.17. Anon., The Subject of Supremacie (14 June, 1643) [167 illegibles]

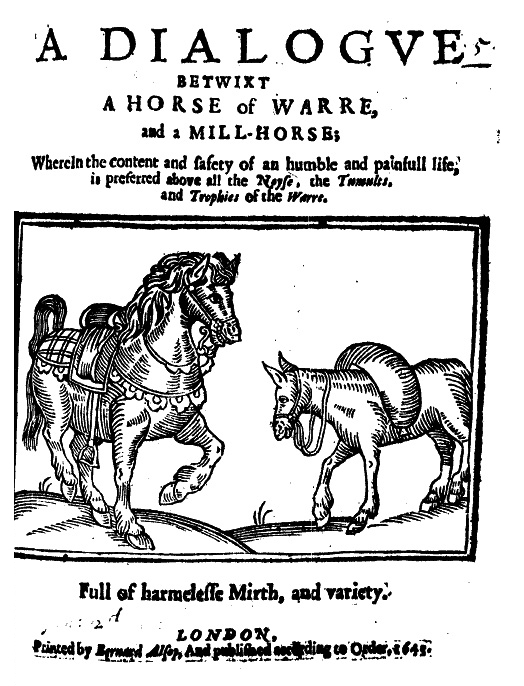

- 8.18. Anon., A Dialogue betwixt a Horse of Warre and a Mill-Horse (2 January, 1644) [48 illegibles]

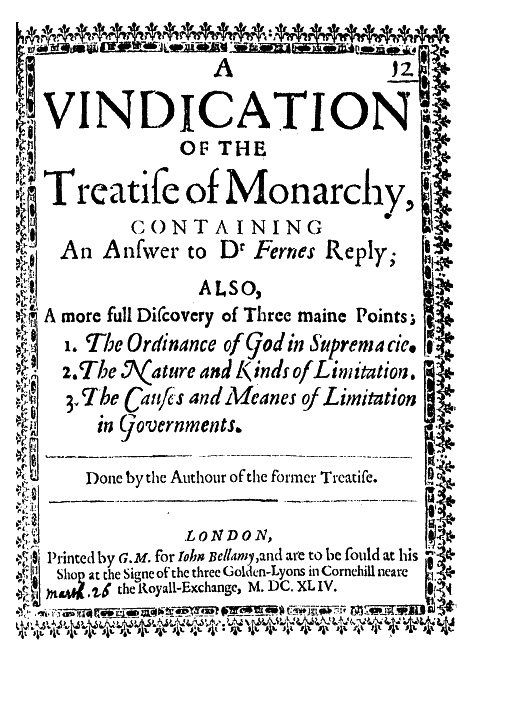

- 8.19. Philip Hunton, A Vindication of the Treatise of Monarchy (26 March, 1644) [38 illegibles]

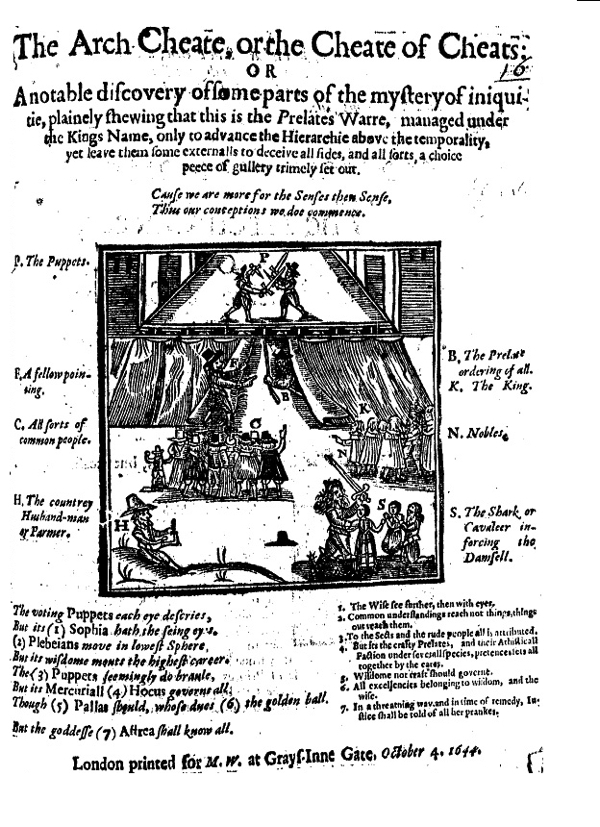

- 8.20. Anon., The Arch-Cheate, or the Cheate of Cheats (4 October, 1644) [54 illegibles]

- 8.21. Katherine Chidley, A New Years Gift (2 January, 1645)[missing text]

- 8.22. Thomas Johnson, A Discourse on Freedome of Trade (11 April, 1645) [2 illegibles]

- 8.23. John Lilburne, Respecting the Power of Disposing of the Militia (30 August, 1645) [1 illegible]

- 8.24. John Lilburne, Englands Miserie and Remedie (14 September, 1645) [29 illegibles]

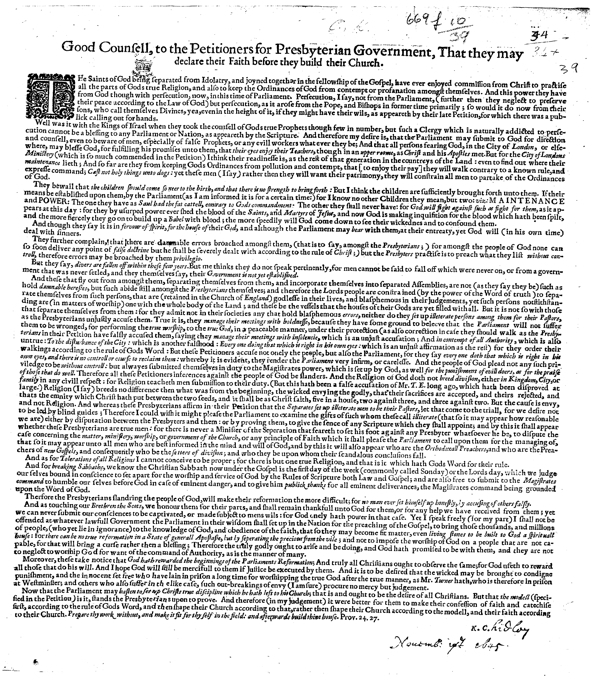

- 8.25. Katherine Chidley, Good Council to the Petitioners for Presbyterian Government (1 November, 1645)

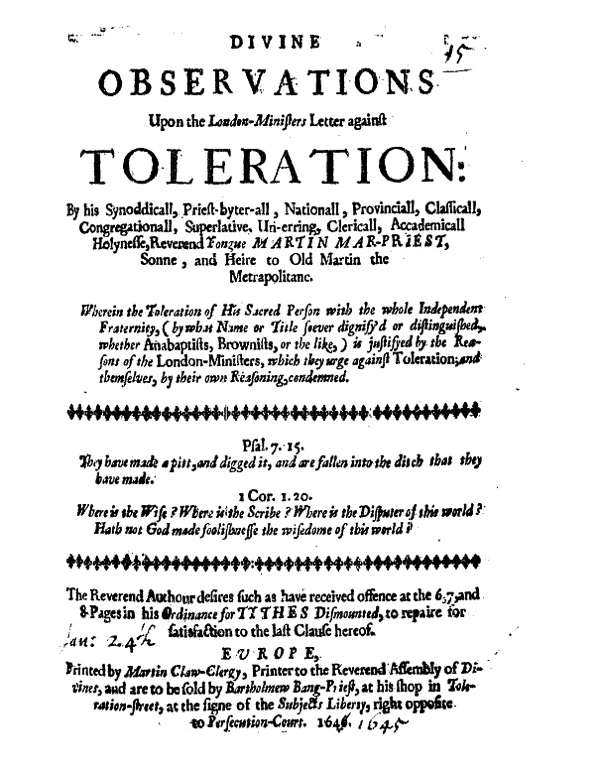

- 8.26. Richard Overton, Divine Observations upon the London Ministers Letter against Toleration (24 January, 1646) [144 illegibles]

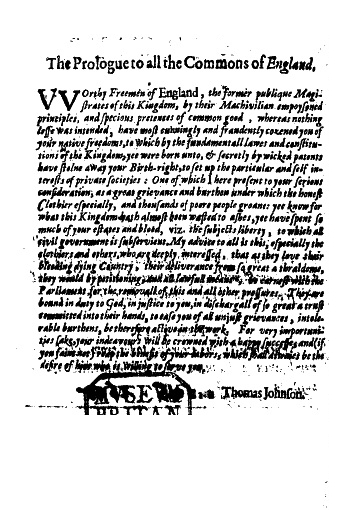

- 8.27. Thomas Johnson, A Plea for Free-Mens Liberties (26 January, 1646) [24 illegibles]

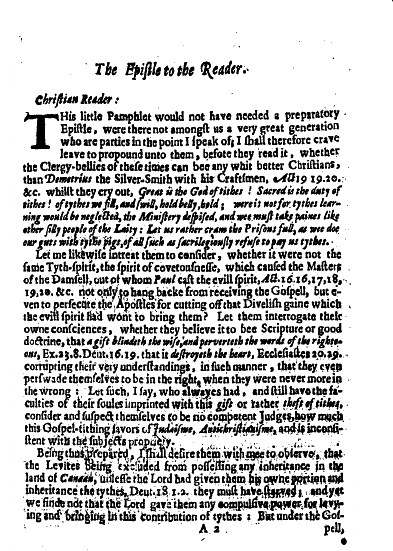

- 8.28. John Selden, Tyth-gatherers, no Gospel Officers (27 January, 1646) [613 illegibles]

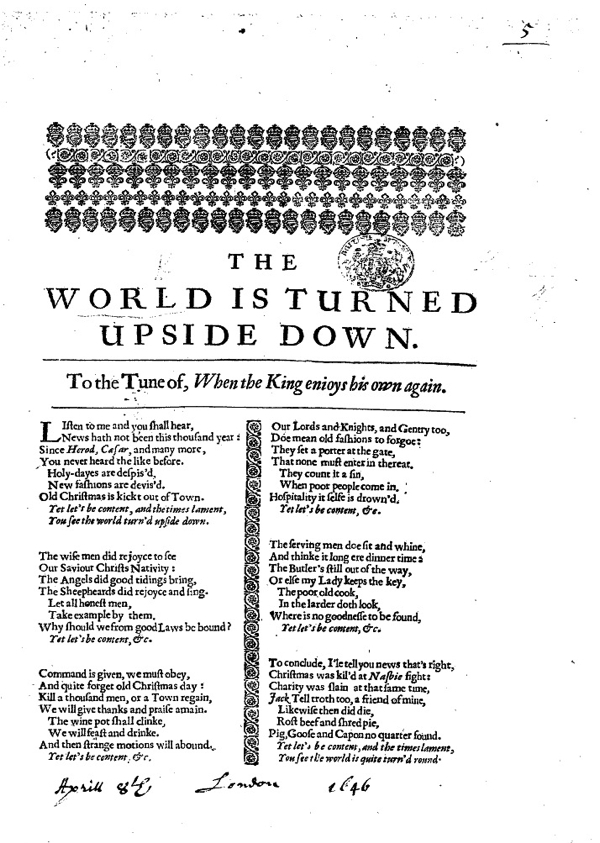

- 8.29. Anon., The World is turned Upside Down (8 April, 1646)

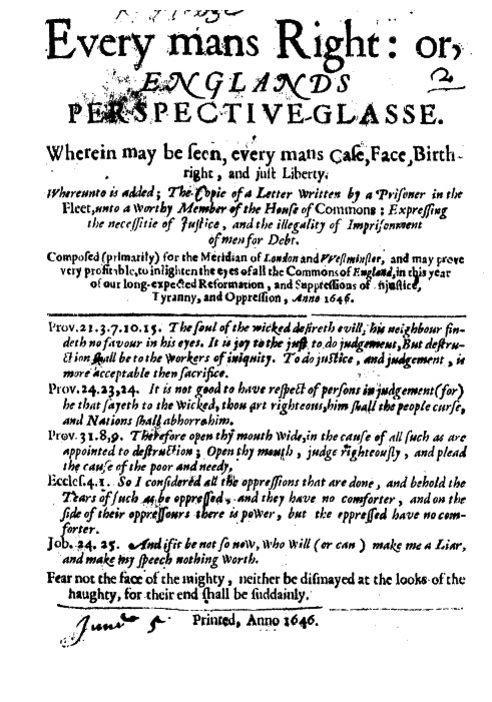

- 8.30. James Freize, Every mans Right (18 April, 1646) [13 illegibles]

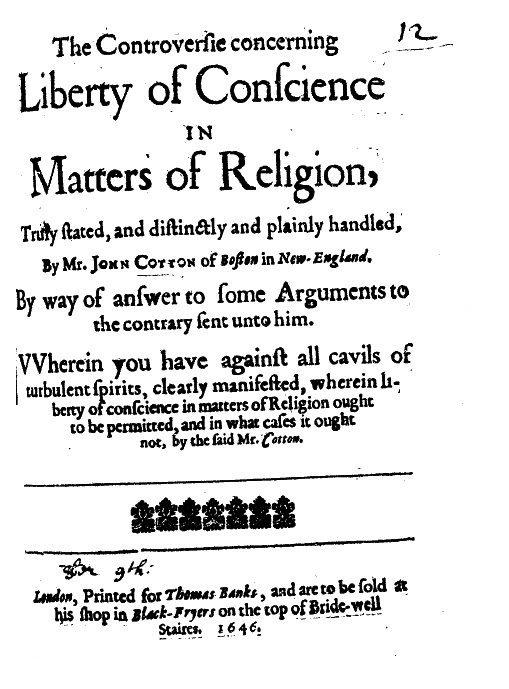

- 8.31. John Cotton, The Controversie concerning Liberty of Conscience (9 October, 1646) [37 illegibles]

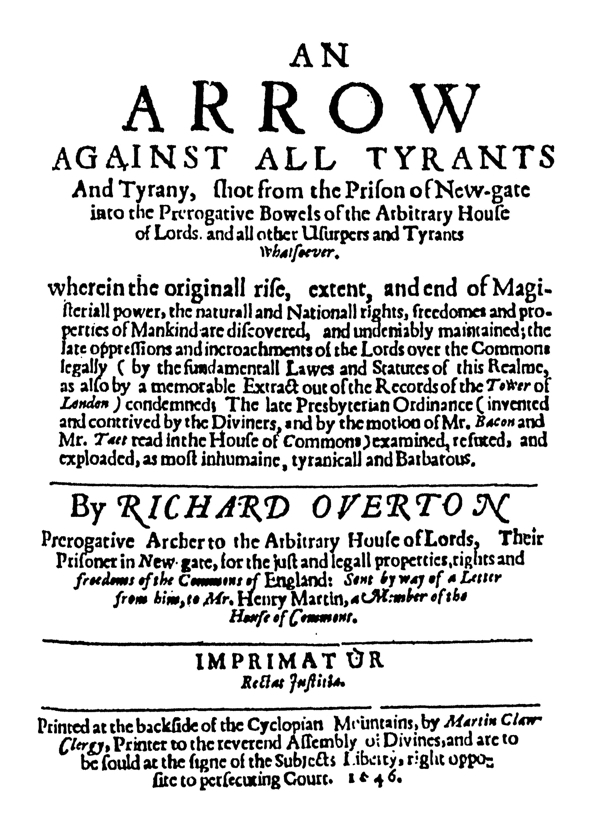

- 8.32. Richard Overton, An Arrow against all Tyrants and Tyranny (12 October, 1646) [46 illegibles]

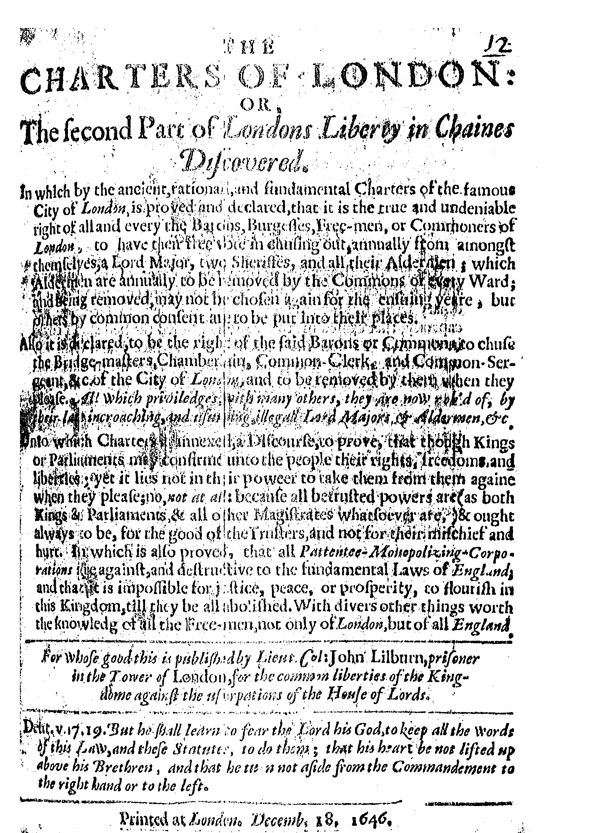

- 8.33. John Lilburne, The Charters of London: or, The second Part of Londons Liberty in Chaines Discovered (18 December, 1646) [244 illegibles]

Editor’s Introduction↩

This collection of pamphlets and tracts is a supplement to earlier volumes in this series which were discovered during the course of their preparation. Publishing information about each title can be found in the catalog of the George Thomason collection (henceforth “TT” for Thomason Tracts):

Catalogue of the Pamphlets, Books, Newspapers, and Manuscripts relating to the Civil War, the Commonwealth, and Restoration, collected by George Thomason, 1640–1661. 2 vols. (London: William Cowper and Sons, 1908).

- Vol. 1. Catalogue of the Collection, 1640–1652

- Vol. 2. Catalogue of the Collection, 1653–1661. Newspapers. Index.

Biographical information about the authors can be found in the Biographical Dictionary of British Radicals in the Seventeenth Century, ed. Richard L. Greaves and Robert Zeller (Brighton, Sussex: The Harvester Press, 1982–84), 3 vols.

- Volume I: A-F

- Volume II: G-O

- Volume III: P-Z

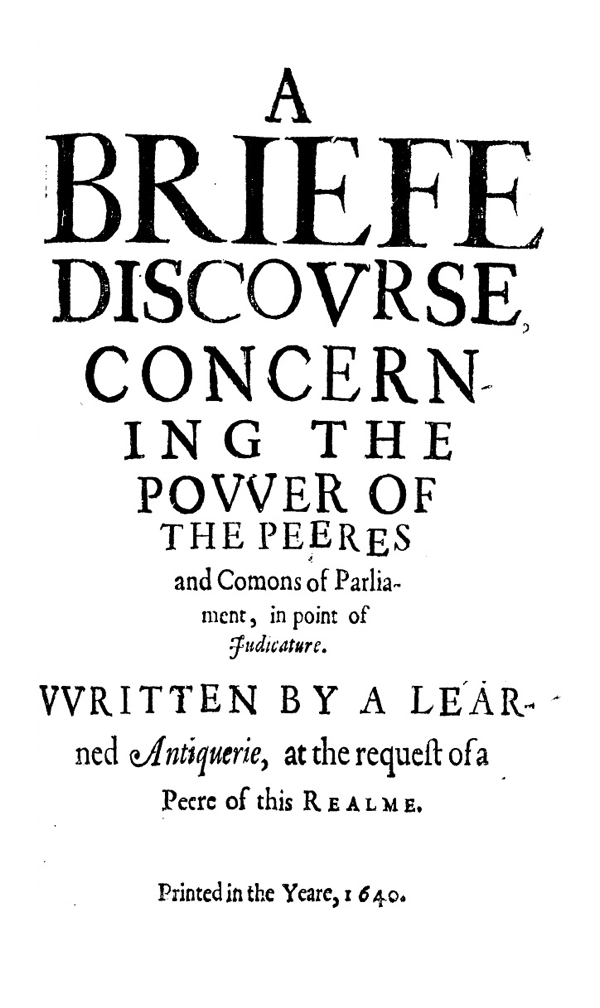

8.1. John Selden, A Brief Discourse concerning the Power of the Peeres (1640)↩

Bibliographical Information

Full title

John Selden, A Briefe Discourse, concerning the Power of the Peeres, and Commons of Parliament, in point of Judicature. Written by a learned Antiquerie, at the request of a Peere, of this Realme. Printed in the yeere, 1640.

Estimated date of publication

1640 (no month given).

Thomason Tracts Catalog information

Not listed in TT.

Editor’s Introduction

(Placeholder: Text will be added later.)

Text of Pamphlet

SIR, to give you as short an account of your desires as I can, I must crave leave to lay you as a ground, the frame or first modell of this state.

When after the period of the Saxon time, Harold had lifted himselfe into the Royall Seat; the Great men, to whom but lately hee was no more then equall either in fortune or power, disdaining this Act, of arrogancy, called in William then Duke of Normandy, a Prince more active then any in these Westerne parts, and renowned for many victories he had fortunately archieved against the French King, then the most potent Monarch in Europe.

This Duke led along with him to this worke of glory, many of the younger sons of the best families of Normandy, Picardy and Flanders, who as undertakers, accompanied the undertaking of this fortunate man.

The Usurper slaine, and the Crowne by warre gained, to secure certaine to his posterity, what he had so suddenly gotten, he shared out his purchase retaining in each County a portion to support the Dignity Soveraigne, which was stiled Demenia Regni; now the ancient Demeanes, and assigning to others his adventurers such portions as suited to their quality and expence, retaining to himselfe dependancy of their personall seruice, except such Lands as in free Almes were the portion of the Church, these were stiled Barones Regis, the Kings immediate Freeholders, for the word Baro imported then no more.

As the King to these, so these to their followers subdivided part of their shares into Knights fees, and their Tennants were called Barones Comites, or the like; for we finde, as in the Kings Writ in their Writs Baronibus suis & Francois & Anglois, the soveraigne gifts, for the most part extending to whole Counties or Hundreds, an Earle being Lord of the one, and a Baron of the inferiour donations to Lords of Towne-ships or Mannors.

As thus the Land, so was all course of Judicature divided even from the meanest to the highest portion, each severall had his Court of Law, preserving still the Mannor of our Ancestours the Saxons, who jura per pages reddebant; and these are still tearmed Court-Barons, or the Freeholders Court, twelue usually in number, who with the Thame or chiefe Lord were Judges.

The Hundred was next, where the Hundredus or Aldermanus Lord of the Hundred, with the cheife Lord of each Townshippe within their lymits judged; Gods people observed this forme in the publike Centureonis & decam Judicabant plebem omni tempore.

The County or Generale placitum was the next, this was so to supply the defect, or remedy the corruption of the inferior, Vbi Curiæ Dominorum probantur defecisse, pertinet ad vice comitem Provinciarum; the Iudges here were Comites, vice comites & Barones Comitatus qui liberas in hoterras habeant.

The last & supreme, & proper to our questio, was generale placitum aupud London universalis Synodus in Charters of the Conquerour, Capitalis curia by Glanvile, Magnum & Commune consilium coram Rege et magnatibus snis.

In the Rolles of Henry the 3. It is not stative, but summoned by Proclamation, Edicitur generale placitum apud London, saith the Booke of Abingdon, whether Epium Duces principes, Satrapæ Rectores, & Causidici ex omni parte confluxerunt ad istam curiam, saith Glanvile: Causes were referred, Propter aliquam dubitationem quæ Emergit in comitatu, cum Comitatus nescit dijudicare. Thus did Ethelweld Bishop of Winchester transferre his suit against Leostine, from the County ad generale placitum, in the time of King Etheldred, Queene Edgine against Goda; from the County appealed to King Etheldred at London. Congregatis principibus & sapaientibus Angliæ, a suit between the Bishops of Winchester and Durham in the time of Saint Edward. Coram Episcopis & principibus Regni in presentia Regis ventilate & finita. In the tenth yeere of the Conquerour, Episcopi, Comites & Barones Regni potestate adversis provinciis ad universalem Synodum pro causis audiendis & tractandis Convocati, saith the Book of Westminster. And this continued all along in the succeeding Kings raigne, untill towards the end of Henry the third.

AS this great Court or Councell consisting of the King and Barons, ruled the great affaires of State and controlled all inferiour Courts, so were there certaine Officers, whose transcendent power seemed to bee set to bound in the execution of Princes wills, as the Steward, Constable, and Marshall fixed upon Families in fee for many ages: They as Tribunes of the people, or ex plori among the Athenians, growne by unmanly courage fearefull to Monarchy, fell at the feete and mercy of the King, when the daring Earle of Leicester was slaine at Evesham.

This chance and the deare experience Hen. the 3. himselfe had made at the Parliament at Oxford in the 40. yeare of his raigne, and the memory of the many straights his Father was driven unto, especially at Rumny-mead neare Stanes, brought this King wisely to beginne what his successour fortunately finished, in lessoning the strength and power of his great Lords; and this was wrought by searching into the Regality they had usurped over their peculiar Soveraignes, wherby they were (as the Booke of Saint Albans termeth them.) Quot Dominum tot Tiranni.) and by the weakning that hand of power which they carried in the Parliaments by commanding the service of many Knights, Citizens, and Burgesses to that great Councell.

Now began the frequent sending of Writs to the Commons, their assent not onely used in money, charge, and making Lawes, for before all ordinances passed by the King and Peeres, but their consent in judgements of all natures whether civill or criminall: In proofe whereof I will produce some few succeeding Presidents out of Record.

Liber S. Alban, so. 20. &illegible; An. 44. H. 3.When Adamor that proud Prelate of Winchester the Kings halfe brother had grieved the State by his daring power, he was exiled by joynt sentence of the King, the Lords & Commons, and this appeareth expressely by the Letter sent to Pope Alexander the fourth, expostulating a revocation of him from banishment, because he was a Church-man, and so not subject to any censure, in this the answer is, Si Dominus Rex & Regni majores hoc vellent, meaning his revocation, Communitas tamen ipsius ingressũ in Angliã iam nullatemus sustineret. The Peeres subsigne this Answer with their names and Petrus de Mountford vice totius Communitatis, as speaker or proctor of the cõmons.

Charta orig. sub sigil. An. &illegible; H. &illegible;For by that stile Sir John Tiptofe, Prolocutor, affirmeth under his Armes the Deed of Intaile of the Crowne by King Henry the 4. in the 8. year of his raigne for all the Commons.

The banishment of the two Spencers in the 15. of Edward the second, Prelati Comites & Barones et les autres Peeres de la terre & Communes de Roialme give consent and sentence to the revocation and reversement of the former sentence the Lords and Commons accord, and so it is expressed in the Roll.

In the first of Edw. the 3.Rot. Parl. &illegible; E. 3. vel. &illegible; when Elizabeth the widdow of Sir John de Burgo complained in Parliament, that Hugh Spencer the yonger, Robert Boldock and William Cliffe his instruments had by duresse forced her to make a Writing to the King, whereby shee was despoiled of all her inheritance, sentence is given for her in these words, Pur ceo que avis est al Evesques Counts & Barones & autres grandes & a tout Cominalte de la terre, que le dit escript est fait contre ley, & tout manere de raison si fuist le dit escript per agard del Parliam. dampue elloques al livre a la dit Eliz.

In An. 4. Edw. 3.Prelationrs Parliam. 1. Ed. 3. Rot. 11. it appeareth by a Letter to the Pope, that to the sentence given against the Earle of Kent, the Commons were parties aswell as well as the Lords & Peeres, for the King directed their proceedings in these words, Comitibus, Magnatibus, Baronibus, & aliis de Communitate dicti Regni ad Parliamentum illud congregatis injunximus ut super his discernerent & judicarent quod rationi et justitiæ, conveniret, habere præ oculis, solum Deum qui eum concordi unanimi sententia tanquam reum criminis læsœ majestatis morti adjudicarent ejus sententia, &c.

&illegible; Ann. 5. &illegible;When in the 50. yeere of Ed. 3. the Lords had pronounced the sentence against Richard Lions, otherwise then the Commons agreed they appealed to the King, and had redresse, and the sentence entred to their desires.

&illegible; Ann 1. &illegible; 11. 3. &illegible;When in the first yeere of Richard the second, William Weston and John Jennings were arraigned in Parliament for surrendring certaine Forts of the Kings, the Commons were parties to the sentence against them given, as appeareth by a Memorandum ãnexed to that Record. In the first of Hen. the 4, although the Commons referre by protestation, the pronouncing of the sentence of deposition against King Rich. the 2. unto the Lords, yet are they equally interessed in it, as it appeareth by the Record, for there are made Proctors or Commissioners for the whole Parliament, one B. one Abbot, one E. one Baron, & 2. Knights, Gray and Erpingham for the Commons, and to inferre that because the Lords pronounced the sentence, the point of judgement should be onely theirs, were as absurd as to conclude, that no authority was best in any other Commissioner of Oyer and Terminer then in the person of that man solely that speaketh the sentence.

The following marginalia text is unreadable and Liberty Fund has made no effort to partially transcribe it.In 2. Hen. 5. the Petition of the Commons importeth no lesse then a right they had to act and assent to all things in Parliament, and so it is answered by the King; and had not the adjournall Roll of the higher house beene left to the sole entry of the Clarke of the upper House, who, either out of the neglect to observe due forme, or out of purpose to obscure the Commons right & to flatter the power of those he immediately served, there would have bin frequent examples of al times to cleer this doubt, and to preserve a just interest to the Cõmon-wealth, and how conveniently it suites with Monarchy to maintaine this forme, left others of that well framed body knit under one head, should swell too great and monstrous. It may be easily thought for; Monarchy againe may sooner groane under the weight of an Aristocracie as it once did, then under Democracie which it never yet either felt or fear’d.

FINIS.

8.2. John Davies, An Answer to those Printed Papers by the late Patentees of Salt (1641)↩

Bibliographical Information

Full title

An Answer To Those Printed Papers published in March last, 1640. by the late Patentees of Salt, in their pretended defence, and against free trade.

Composed by IOHN DAVIES Citizen and Fishmonger of London, a well-wisher to the Common-wealth in generall.

Sal sapit omnia. Ne scis quid valeat.

Printed in the yeare, 1641.

Estimated date of publication

1641 (no month given).

Thomason Tracts Catalog information

Not listed in TT.

Editor’s Introduction

(Placeholder: Text will be added later.)

Text of Pamphlet

THe ensuing Treatise, concerning the opposing of the project and Patents for Salt, tending to the good of his Majesty, and of the Subjects in generall, (wherein all faithfull endeavours on the Authours part are performed) is most humbly presented, praying, that if any error is therein committed, (whereof he is not conscious) may by this Honourable Assembly be pardoned.

An Answer to those Papers (falsly intituled, A true Remonstrance of the state of the Salt businesse, &c.) lutely published in print in March. 1640. by the Projectors of the first and second Patents for Salt, in their owne pretended defence, and against the free trade of all Merchants, Navigators, and Traders for Fish and Salt of the City of London, and all other Ports, and of all Salt makers and Salt refiners, and of all other his Majestces Subjects within the extent of their severall Patents betweene Barwicke and Weymouth, as followeth.

IN this Answer it will not be necessary to bee limited within the strict time where the Projectors began which was in Anno 1627. thereby to serve their own occasions, but is intended to declare the truth of the most usuall and constant prices of Salt at the City of London; as, it hath beene sold for 40. yeares last past, as in the sequell shall appeare.

That in Anno 1600. even till the latter part of the yeare, 1627. the most usuall price either of white or bay Salt, was neare about 50. s. or 3. l. a Wey, and often sold under that price, as can be sufficiently proved.

That in the said yeare 1627. the Watres began betweene the Kings Majesty of Great Britaine, and the French King, and the King of Spaine; in which time, till the peace was concluded betwixt those Kings, the commoditie of Salt was very deare and scarce, especially French Salt, which was at 6. s. or 7. s. a bushell at the City of London, which came to passe in regard the Salt-workes in France were destroyed.

First, at the Ile of Ree by the Duke of Buckinghams designe.

Secondly, by the French King himselfe in the warres when he tooke in Rochel.

And thirdly, by intemperate Raine which fell that time in France. So that the Kingdome of France it selfe, which was wont to supply many other parts, as England, Ireland, Holland, the Eastland, and Germany, was thereby necessitated with want of that commodity for its owne occasion. And therefore not to be admired, that the French King made an Edict in Anno 1630. that no Salt should bee exported out of his Kingdome, (untill his store should bee supplyed againe.) Which scarcity in France for that present, forced all men to send into Spaine for Salt, and thereupon a great number of Ships from all parts arriving there at one time, gave the King of Spaine occasion to make use of the present necessity, and layd a great Impost on the Salt that should bee transported from thence.

The very same cause also moved the Kings Majesty of Great Britaine, and the Lords of the Councell, to order in that time of scarcity of Salt, by meanes of a Petition exhibited to the Lords by the Lord Maior of the City of London, and divers other Ports in Anno 1630. that no Salt should be transported into any forraigne parts, which was effectually granted them by the Lords. But when in one or two yeares after, and that in France there were erected Salt-workers, and Salt was made plentifully againe, as in the yeare 1632. then by the Edicts of the said Kings, the great imposition of Salt in Spaine and France ceased, and Salt became cheape againe, and Trade free as in former yeares, as about 3. l. or 3. li. 10. s. per Wey, for English or French, and 4. l. per Wey for Spanish Salt at most, which continued till December, 1634.

So that the cause of the dearth of Salt in France, Anno 1628. till Anno 1632. hapned through Warre and intemperate Weather, as before is specified, and not by the pleasure of Princes, by laying of a great Impost upon it, as they the Patentees falsly pretended; but the Projectors were desirous to make that an occasion of bringing their covetous desires to effect, and about that time they beganne to devise to bring an Impost on the English native Salt, which was and is dearer to the makers of it then any other salt spent in this Kingdome. For French and Spanish Salt being made onely by the heat of the Sunne, stands not the makers of it in above 10. s. or 20. s. or 30. s. a London Wey at the most, according to the drinesse, or the wetnesse of the Summer, whereas the English Shields Salt at 1. d. per Gallon, (which is the cheap price the Patentees boast of stands the makers of it in 53. s. 4. s. the like Wey at least, being also the weakest Salt of all other by one third part, and therefore cannot be are any Impost, without destroying the English manufactures, as these Projectors have all this time practised, to the destruction thereof, although they pretended the contrary.

It is to be observed, that a Wey of Salt at the City of London, containeth 40. Bushels, and every Bushell 10. Gallons, which is the right measure according to the Statute; from which, in most other Ports it much differeth.

That in December, 1634. the first Projectors, consisting of twenty two in number, (whereof five were Knights, the other seventeene had the titles of Esquires and Gentlemen) having determined and practised formerly to doe mischiefe in this Land wherein they were borne and bred, and being all or most of them unexperienced in the matter they tooke in hand, devised and obtained this Monopoly of Salt, mis-informing his Majesty, and the Lords of the Councell, that it would be a great benefit to this Kingdome of England, and that of Scotland, to erect workes for the making a sufficient quantity of Salt, &c. and at a certaine moderate price, (as they so termed it) not exceeding 3. l. a Shields Wey, which is after the rate of 5. l. 12. s. for a Wey delivered at London, which is an intolerable exaction upon a native manufacture, made and spent in this Kingdome, as by their Patent more fully doth appeare; (although the Salt pannes in those places were erected long before, and not by these Patentees.) Which Patent being obtained by them, they practised to oppresse the Subject from January 1635. untill August 1638. all which time the first Patentees having made a Monopoly, in taking all the old Workes and Pannes at the Shields into their hands, forced white Salt at the City of London to the price of 4. l. 15. s. per Wey, and for the most part to 5. l. per Wey, and so in all other Ports according to that rate.

And Bay Salt by reason of their great Impost of 48. s. 6. d. per Wey, which was raised by a privy Seale, procured by Edward Nattall, and others his associates, (but nothing brought to accompt for his Majesty, as yet appears) was not all that time sold at London under 5. l. 10. s. per Wey, at least, but commonly at 5. l. 13. s. 4. d. per Wey, or 6. l. whereas the Westerne parts, which were free of their Patent, as Southampton, Exeter, Plimouth, Bristol, &c. had it in that time at or about 3. l. the like Wey, and sometimes under that price, which was most unjust and unequall, that the Easterne parts should suffer so much thereby, not onely in the price, but also in hindrance of Navigation, and losse of Trade.

That about July, 1638. the first Patentees having difference with Master Murford of Yarmouth, who had a Patent granted before theirs at Shields, prevailed against them, and some of them of the first Patent being wearied with the designe, voluntarily laid downe their Patent.

That after the first Patentees gave over their Patent, the Salt-makers at Shields in August, 1638. reassumed their Pannes, and sold Salt there cheape againe, and thereby both Scottish and Shields Salt was sold at London for 3. l. per Wey, or near thereabout, untill January following, that Thomas Horth and his associates obtained a grant of their Patent, which they presently after put in execution, yet Horth and his associates of the second Patent had no time to raise the price of white Salt at Shields to that height as they desired, for the Scots presently after the first Pacification in August, 1639. brought it downe at London to 2. l. 17. s. per Wey, whereas Horth and his Associates in June and July 1639. would sell none at London under 4. l. 10. s. per Wey.

That whereas the first and second Projectors of both Patents, to cleare themselves of the great wrong done by them to his Majesty and his Subjects, doe in their printed Papers lay the blame on the traders in Salt of the City of London, seeking therby to glosse over their oppressing the Subjects even in the face of this Honourable Parliament, still pretending as formerly, that what they did was for his Majesties profit, benefit of Navigation, support of home manufacture, and generall good of the subject, and many such like things, all which pretences are meere falshoods and suggestions.

For first his Majesties Revenew is no way increased, as doth appeare by their payments into his Majesties Exchequer, being in all but 700. l. whereas they have received Impost, and remaine debtors to his Majesty many thousands, as by further examination and proofe of their accompts will appeare.

Secondly, Navigation hath beene much hindred thereby, as by a former Petition of the Trinity house to his Majesty and the Lords of the privy Councell appeareth, as also it hath beene sufficiently proved before the Committee for the Salt businesse, by the Master and Wardens of the Trinity Company, who are most sensible of the destruction and advancement of the Shipping and Navigation of this Kingdome.

Thirdly, they have so cherished the home manufacture, by laying a heavy Impost upon it, that those that had 240. Pannes of their own, and were thriving people at the Shields, before their Patents were of force, and were the makers there of Salt, are by the meanes of these Patentees become so poore, that the greater part of them are not able to buy coals to set their Pannes on worke. And those the Patentees who bought 34. Pannes of the old traders, did cease working for the most part of the years 1639. and 1640. by reason they could not attaine to their intended price of 56. s. 8. d. per Wey at the Shields. So that whereas there was formerly made at the Shields before their Patents began about 16000. Wey per annum, they made in the time of the first Patent, which continued about three yeares and a halfe, not above 10000. Wey per annum. And in the time of the latter Patent but 8000. Wey per annum, even before the comming in of the Scottish Army into those parts: by all which appeares how much they have destroyed the native manufacture, and have no wayes advanced or increased it, as they pretended.

Fourthly, for their pretences of the generall good of the Subject, in place whereof they have so oppressed the Subject in generall, that not onely the traders in Salt of the City of London, have justly complained of their grievances to the Honourable Court of Parliament, but also Salt-refiners of Essex and Suffolke, also many Merchants in the West parts as far as Weymouth, as also from Yarmouth, and many other ports North as farre as Newcastle, that came up to London onely to informe the Court of Parliament of the great burden they have beene forced to lye under, even to many of their undoings: And many more would come up, had they not beene so impoverished by them the Patentees, that they are not able to beare their charges in comming so farre to complaine of their grievances. In generall, they have been the oppressors of Fishermen, and all the subjects of these North East parts of England, to the value of many thousand pounds in estimation, above fourescore thousand pounds since the time of their entring into these Patents, which can be made plainly to appeare by one yeares importation for forraigne and Scottish Salt, collected out of the Custome-house bookes, and Meters bookes of London, and for native Salt out of their owne bookes.

Viz.

In the yeare 1637. (which was in the time of their first Patent) of Bay and Spanish Salt there was imported but 1364. Wey, which at 48. s. 6 d. per Wey, is impost 3307. l. 14. s. whereas in the yeare 1634. when the trade was free there was 4620. Wey of forraigne Salt imported, by which may be observed the decay of forraigne Trade during the time of their Impost.

That the Impost of forraigne Salt was received and taken of all the Subjects between Barwicke and Southampton, by vertue of Privy Seale dated in May 1636. procured by Edward Nattall, and others his associates, but nothing brought to accompt by them, nor paid to his Majesties use for the two yeares and 6. moneths, (as can yet appeare.)

That of Scottish and native white Salt Shields measure, there were expended for land use about 16000. Weyes, which at 10. s. per Wey Impost, and 10. s. per Wey increase of price, which came to passe by the Patentees contracting with the Scotch for deare selling, and can appeare to be damage to the subjects at least in one yeare, in the price of the white Salt 16000. l.

That for Fishers use of Scottish and native Salt, an estimate of 3000. Shields Wey, and upwards, at 3. s. 4. d. per Wey Impost, and 6. s. 8. d. increase of price, is at least 1500. l.

Whereby it appeares that the subjects suffered in one yeare by the first Salt Patents, &illegible; l. 15. s.

That the Patentees for Salt continued their first and second Patents above 5. yeares.

By all which it is manifest how profitable these Patents have beene to the Patentees, how little benefit hath accrued to his Majesty thereby, how great a burden to the Subjects in generall, and to the old Salt makers, and the Merchants for forraigne Salt, and all Fishermen, who use great quantities thereof, and to all traders in the same in their particulars. But if any trader in Salt hath either joyned with those Patentees in any indirect way, thereby to uphold them, or the extreme price of Salt, they are not hereby intended to be excused, but to be left to the consideration of the Honourable House of Parliament.

And whereas Horth and his Associates seek to justifie their Patent, comparing it with that which Master Murford intended (which would also have beene alike illegall with theirs, by laying an Impost on native Salt (as they have practised.)

For answer thereunto is said, that the unlawfulnesse of Murfords Patent intended, cannot make that of Horths to bee lawfull which was practised by him. For as well that of Horths, as also the first Patent, have beene sufficiently discussed by the Committee appointed by the Honourable House of Commons now assembled in Parliament, for the hearing of that businesse, and is by them most justly condemned to be illegall, a Monopoly, and prejudiciall to the Commonwealth. For so it is, that a Monopoly is a kinde of commerce in buying and selling usurped by a few, and sometimes by one person, and forestalled by them or him from all others, to the gaine of the Monopolist, and to the detriment of other men.

That the latter Patentees further proceed in their justification, declaring the low rates the subjects have beene served at since the time of the settlement of their Patent, which is (as they say) at 1. d. ob. per Gallon at the most, which in truth is a most intolerable exaction on the subject. For 1. d. ob. per gallon is no lesse then 50. s. a Shields Wey, which is but five eight parts of a London Wey, and so the fraught being added, which is 10. s. a Shields Wey, without Impost, it will stand the Adventurer in no lesse then 4. l. 16. s. a Wey London measure, whereas it may bee afforded, delivered at London, for 3. l. 12. s. per Wey, which is after the rate of 35. s. per Wey to the Salt makers at Shields for their Wey, at which said price of 35. s. per Wey, the old Salt makers say, they can afford it, but not under.

And for the rate of 1. d. per Gallon, which is the cheape price they so much boast on, it being but 33. s. 4. d. a Wey Shields measure, at which price, if they sold any so cheape, it was much against their wills, for they desired and alwayes sought to settle it at 56. s. 8. d. per Wey Shields measure for land use, and 46. s. 8. d. for the fishing Sea expence, which are the prices laid downe in the latter Patent: yet it is true, that they sold some at lower rates: but they were forced thereto by meanes of the great plenty that was brought in by the Scots, who sold it at London, Yarmouth, and some other Ports at 3. l. a Wey, in Anne 1639. and some under that price, as aforesaid, whereupon the Patentees gave over making Salt at Shields in their 34 pannes, in regard they could not attaine to their intended price of 56. s. 8. d. a Shields Wey, yet some of the old Salt makers still wrought, (though to their great losse, and some of their undoings) selling it not for above 30. s. per Wey, yet notwithstanding they the Patentees took of them the old Saltmakers, without any moderation or compassion, the full impost of 10. s. for every Shields Wey, for Land use, and 3. s. 4. d. per Wey, for the fisliery expence. For they had forced the old Saltmakers and Salt refiners to enter into bond, for the payment therof unto them, which if they refused to do, they violently forced them of the Sheilds, of great Yarmouth, and Salt Refiners of Essex and Suffolke thereunto by imprisoning of some, committing of others into Pursuivants hands, and causing others to come up and answer at the Councell Table, to their great expence both of money and time, which extreamity Horth used in that time he was governour more then any other either of the first or second Patentees.

That in the Months of September, October and November last, Salt became decret then it was in eight or nine yeares before, which came to passe partly by reason of the great impost continued by the Patentees of the last Patent, both on the native and forraigne Salt, and partly by reason of the imbarring of the Scottish trade, and the comming in of the Scottish Army, at that time into Newcastle and Shields, so that white Salt was sold in October last at the port of London at 6. l. 10. s. per Wey, and Bay Salt in November last, was sold at the port of London for 8. l. per Wey, in regard Master Strickson, Master Nuttall, and Master Duke, three of the last Patentees continued the taking impost even untill this present Parliament, which three were also chiese of the Projectors of the first Patent.

That the 23. of November last, the Honourable Assembly of Parliament upon a Petition of the traders in Salt of London, injoyned the Patentees to bring in their Patents & cease taking impost, and thereupon the price both of White and Bay Salt did fall at the port of London to 3. l. a Wey, and some for lesse: but the windes proving contrary in the latter part of December, January and February last, for above ten weekes together: And also small store of Salt having been laid up in London, or made at Shields by reason of the troubles in those parts with the Scottish Army, the store of white Salt for want of supply was soone spent here at London: and had it not beene that the Parliament before that time had taken off the Impost of forraigne Bay and Spanish Salt, whereby there was good quantities of forraigne Salt brought in, this City of London had been so necessitated for Salt, as the like hath not been knowne. Yet from the Kings Store house, and the East India Company, and other such like places, there was some small quantities of white Salt found, which supplyed the present want thereof, and was sold in those deerest times at or neere Billingsgate by some of the Traders in Salt for 6. s. 8. d. per Bushell at most, but Bay Salt all that time was sold for 22. d. or 2. s. a bushell, and not above all that time, which was in the Moneth of February, but before that Moneth was expired, and ever since it hath beene sold for 2. s. per Bushell, and five peckes to the Bushell, at or neare Billingsgate.

And whereas the Patentees alledge that white Salt was sold for 2. s. a pecke, at that instant day, when they published their printed papers, it is manifestly to bee proved that ten or twelve daies before they published them, white Salt was cryed in London streets at 5. d. a pecke, and so ever since, which proves their printed papers to be scandalous and false, in laying forth so many imputations upon the Traders in Salt, as though they were the cause of deare selling, which was only their continued impositions, and the occasion of the time as afore is shewed.

That before the Patentees had obtained their Patent for Salt there was imported yearly to London great quantities of Spanish, Straits, and French Salt, by Merchants, Navigators and Traders. And that many hundred Weyes thereof were from thence yearly transported for Flanders, Holland, Denmarke, and the East Countrie, whereby ships had their imployments both inwards and outwards, his Majesties Customes improved, and many poore people, as Porters and Labourers had their maintenance thereby; which trade of Importation is in a manner wholly decayed since the time these severall Patents were obtained.

THat their Patents are found by the Committee appointed by the Parliament for hearing the Salt businesses to be illegall, and a Monopoly, by reason they brought an impost on the native Manufacture, and many other oppressions to the Subject.

That the prosecution hath beene most violent by imprisonments, and forcing many out of their Trades, and also Salt Refiners and Saltmakers, at Shields and great Yarmouth from their works; and the first Patentees forced divers at Shields to let them their Pannes at a Rent, which after two yeares and sixe monthes use, they returned into their hands much decayed, and not satisfied for Rent.

That they would have forced his Majesties Subjects to the only use of white Salt, which is not so sufficient for fishing Voiages and many other uses, as the forraigne.

That they forced the price both of white & Bay Salt, in the time of their Patents, to one third part more then otherwise it would have beene sold for.

That there was a far greater quantity of Salt made in England before their Patents began, then in the time of the continuance of their Patents.

That Horth at a hearing at Councell Table the 19. of December, 1638. to maintaine his unjust cause in taking his Patent, and upon some speech, which was moved about the insufficiency of white Salt for preserving of Fish, and an ancient Trader there saying, that the very scales fell off through the weaknesse of the white Salt; he the said Horth did most falsly reply and affirme, that Codde and Ling Fish had no scales, which he did to convince them of error who came to oppose him: and he with others (whose names are well knowne) did then and there before his Majesty and the Lords of the Councell so farre maintaine it, that they were believed, and that the others that spake the truth, were rejected, whereby the King and Lords were abused by the said Horth and others, by denying that to the creature which it had received in the creation either for defence or ornament.

That it is and hath beene proved both before his Majesty and the Lords, and also before the Committee by the Trinity house Masters, that if forraigne Salt be prohibited, or some heavy impost be laid upon it, Navigation will be much hindred and decaied.

That Horth alone above the rest of his partners obtained a Commission out of the Exchequer, and did thereby put men to their corporall oaths, to confesse what Salt of their owne or of others, they knew to be imported, and told the Commissioners hee was at Councel about that particular, and his Councell advised him, it must bee so, and to bee sure, would bee with the Commissioners himselfe, and urge it.

That the settled moderate rate (as the Patentees pleased to call it) of 56. s. 8. d. per Wey Shields measure, will stand the Adventurer delivered at London in 5. l. 6. s. 8. d. per wey, which is now since their Patent ceased sold at this City of London for 3. l. 10. s. per wey, and long before their Patents began, it was sold cheaper, (that time of three or foure yeares of hostility with France and Spaine, when there could be little forraigne Salt imported, onely excepted.) And Bay Salt at present is sold at 3. l. per wey.

That beyond the power of the Patents, Horth constrained the Salt refiners of divers. Counties to pay a double Impost.

That if the commodity of Salt be free for all men to import, or make it, there cannot be that ingrossing, forestalling, or regrating made which may be done by a few monopolizing Patentees, who having the command of it all, may conferre the commodity upon some few particular Traders, for some sinister respects, to the destruction of others in their Trades, (as the late times of their Patents have made manifest.) And for those 27. yeares afore specified, the commodity of Salt being then free of Impost, the price was alwayes reasonable, and would be so now, and so continue, without the helpe of any Projector.

That a free trade which is now so much desired of the subject, and a settled price, desired of the Patentee, cannot consist, for a constant price forced upon a native manufacture is a principall part of a Monopoly.

That forraigne Salt being absolutely necessary for speciall uses, the inhibition thereof cannot be admitted, but to the great prejudice of the subject.

That these Projectors, which pretend so much of supporting the home manufacture of Salt, have in a maner destroyed it, by laying so heavy an Impost upon it, as 16. s. for every London Wey. And if it be not supported by taking off the foresaid Impost, it is like utterly to decay, and then indeed (the Salt Wiches onely excepted) this Kingdome must wholly depend upon forraigne parts, for all the Salt shall be therein expended.

(The premises considered) the humble request to the Honourable House of Commons now assembled in PARLIAMENT, is, That they would be pleased, that the Projectors and late Patentees for Salt may be brought to an account upon the premisses, that so it may appeare what profits have accrued to his Majesty, and what disadvantage to the Subject, and what persons have beene molested and vexed by reason of them, that so reparations and redresse may be made to the parties so vexed and grieved, as in the judgement of the Honourable Assembly shall be thought expedient.

FINIS.

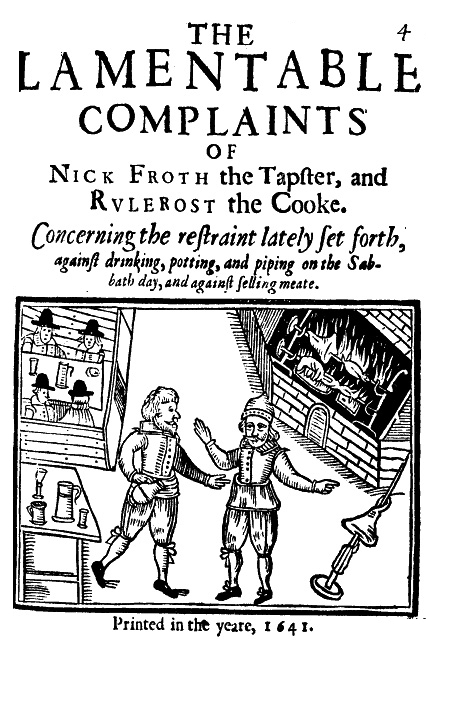

8.3. Anon., The Lamentable Complaints of Nick Froth the Tapster (May 1641)↩

Bibliographical Information

Full title

Anon., The Lamentable Complaints of Nick Froth the Tapster, and Rulerost the Cooke. Concerning the restraint lately set forth against drinking, potting and piping on the Sabbath Day, and against selling meate. Printed in the yeare, 1641.

Estimated date of publication

May, 1641.

Thomason Tracts Catalog information

TT1, p. 14; Thomason E. 156. (4.)

Editor’s Introduction

(Placeholder: Text will be added later.)

Text of Pamphlet

Concerning the restraint lately set forth, against drinking, potting, and piping on the Sabbath-day, and against selling meate.

MY honest friend Cooke Ruffin well met, I pray thee what good newes is stirring.

Good news (said you?) I, where is’t? there is such newes in the world, will anger thee to heare of, it is as bad, as bad may be.

Is there so? I pray thee what is it, tell me whatsoever it be.

Have you not heard of the restraint lately come out againstus, from the higher Powers; whereby we are commanded not to sell meat nor draw drink upon Sundays, as we wil answer the contrary at our perils.

I have heard that some such thing was intended to be done, but never before now, that it was under black and white: I hope there is no such matter: Art thou sure this thy news is true?

Am I sure, I ever roasted a fat Pig on a Sunday untill the eyes dropt out, thinke you. S’foot, shall I not credit my owne eyes.

I would thine had dropt out too, before ever thou hadst seen this, and if this be your news, you might have kept it, with a pox to you.

Nay, why so chollerick my friend, you told me you would heare me with patience, whatsoever it were.

I cry thee heartily mercy, honest Rulerost, I am sorry for what I said, it was my passion made me forget my self so much: but I hope this command as you speake, will not continue long, will it thinke you Master Cooke?

Too long to our greife I feare, the Church-Wardens, Side-men, and Constables, will so look to our red Lattices, that we shall not dare to put our heads out of doors on a Sunday hereafter. What think you neighbour, is it not like to prove so?

Truely it is much to be feared; but what do you think will become of us then, if these times hold?

Faith, Master Froth, we must shut up our doors and hang padlocks on them, and never so much as take leave of our Land-lords.

Master Rulerost, I jumpe with you in opinion for if I tarry in my house till quarter-day, my Land-lord, I feare, will provide me a house gratis. I am very unwilling to trust him, he was alwayes wonderfull kind, and ready to help any of his debtors to such a curtisie; to be plaine with you, I know not in which of the Compters I shall keep my Christmas, if I doe not wisely by running away prevent him.

Thou hast spoke my owne thoughts, but I stand not so much in danger of my griping Land-lord, as I doe of Master Kill-calfe my Butcher, I am run into almost halfe a yeares arrerages with him; I do owe him neare ninety pounds for meat, which I have had of him at divers and sundry times, as by his Tally, may more at large appeare.

I my selfe am almost as farre in debt to my Brewer, as you are to your Butcher; I had almost forgotten that, I see I am no man of this World; if I tarry in England: He hath often threatned to make dice of my bones already, but ile prevent him; ile shew him the bagg, I warrant him.

He had rather you would shew him the money and keep the bagge to your selfe.

I much wonder, Master Rulerost why my trade should be put downe, it being so necessary in a Common-wealth: why, the noble art of drinking, it is the soule of all good fellowship, the marrow of a Poets Minervs, it makes a man as valiant as Harcules, though he were as cowardly as a French man; besides, I could prove it necessary for any man sometimes to be drunk, for suppose you should kill a man when you are drunk, you shall never be hanged for it untill you are sober; therefore I thinke it good for a man to be alwayes drunk: and besides it is the kindest companion, and friendliest sin of all the seven; for most fins leave a man by some accident or other, before his death. But this will never forsake him till the breath be out of his body: and lastly, a full bowle of strong beere will drowne all sorrowes.

Master Nick, you are mistaken, your trade is not put downe as you seeme to say; what as done, is done to a good intent; to the end that poore men that worke hard all the weeke for a little money, should not spend it all on the Sunday while they should be at some Church, and so consequently there will not be so many Beggers.

Alack you know all my profit doth arise onely upon Sundays, let them but allow me that priviledge, and abridge me all the weeke besides: S’foot, I could have so scowred my young sparks up for a peny a demy Can, or a halfe pint, heapt with froth. I got more by uttering halfe a Barrell in time of Divine service, then I could by a whole Barrell at any other time, for my customers were glad to take any thing for money, and thinke themselves much ingaged to me; but now the case is altered.

Truely Master Froth, you are a man of a light constitution, and not so much to be blamed as I that am more solid: O what will become of me! I now thinke of the Iusty Surloines of roast Beefe which I with much policy divided into an innumerable company of semy stices, by which, with my provident wife, I used to make eighteene pence of that which cost me but a groat (provided that I sold it in service time,) I could tell you too, how I used my halfe Cans and my Bloomesbury Pots, when occasion served; and my Smoak which I sold dearer then any Apothecary doth his Physick: but those happy dayes are now past, and therefore no more of that.

Well, I am rid of one charge which did continually vex me by this meanes.

I pry thee what was that?

Why Master Rulerost, I was wont to be in see with the Apparitors, because they should not bring me into the Bawdy Court for selling drinke on Sundayes. Ile assure you they used to have a Noble a quanter of me, but now they shall excuse me, they are like to have no more quartridge of me, and indeed the truth is, their trade begins to be out of request aswell as ours.

I, trust me neighbour, I pity them; I was as much troubled with those kind of Rascals as your self, onely I confesse I paid them no quartridge, but they tickled my beefe, a stone of beef was no more in one of their bellies, then a man in Pauls; but now I must take occasion to ease my self of that charge; and with confidence I will now bid them, Walke knave, walke.

Truely Master Rulerost, it doth something ease my mind when I thinke that we have companions in misery. Authority I perceive is quick sighted, it can quickly espie a hole in a knaves coate. But Master Cooke we forget our selves, it groweth neare supper time, and we must part, I would tell you what I intend to doe, but time prevents me, therefore ile refer it untill the next time we meet; And so farewell.

FINIS.

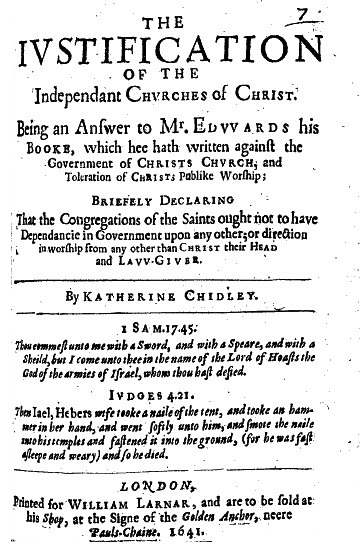

8.4. Katherine Chidley, The Justification of the Independant Churches of Christ (October, 1641)↩

Bibliographical Information

Full title

Katherine Chidley, The Justification of the Independant Churches of Christ. Being an Answer to Mr. EDVVARDS his BOOKE, which hee hath written against the Government of CHRISTS CHVRCH, and Toleration of CHRISTS Publike Worship; BRIEFELY DECLARING That the Congregations of the Saints ought not to have Dependancie in Government upon any other; or direction in worship from any other than CHRIST their HEAD and LAVV-GIVER. By KATHERINE CHIDLEY.

1 SAM. 17. 45. Thou commest unto me with a Sword, and with a Speare, and with a Sheild, but I come unto thee in the name of the Lord of Hoasts the God of the armies of Israel, whom thou hast defied.

IVDGES 4. 21. Then Iael, Hebers wife tooke a naile of the tent, and tooke an ham|mer in her hand, and went softly unto him, and smote the naile into his temples and fastened it into the ground, (for he was fast asleepe and weary) and so he died.

LONDON, Printed for WILLIAM LARNAR, and are to be sold at his Shop, at the Signe of the Golden Anchor, neere Pauls-Chaine. 1641.

Estimated date of publication

October, 1641.

Thomason Tracts Catalog information

TT1, pp. 37–38; Thomason E. 174 (7.)

Editor’s Introduction

(Placeholder: Text will be added later.)

Text of Pamphlet

TO The CHRISTIAN READER; Grace, Mercy, and Peace, from God the Father, and from our Lord Jesus Christ.

IT is, and hath beene (for a long time) a Question more enquired into than well weighed; Whether it be lawfull for such, who are informed of the evills of the Church of England, to Separate from it: For my owne part, considering that the Church of England is governed by the Canon Lawes (the Discipline of Antichrist) and altogether wanteth the Discipline of Christ, and that the most of them are ignorant what it is, and also doe professe to worship God by a stinted Service-Booke. I hold it not onely lawfull, but also the duty of all those who are informed of such evills, to separate themselves from them, and such as doe adhere unto them; and also to joyne together in the outward profession and practise of Gods true worship, when God hath declared unto them what it is; and being thus informed in their minds of the knowledge of the will of God (by the teaching of his Sonne Jesus Christ) it is their duty to put it in practise, not onely in a Land where they have Toleration, but also where they are forbidden to preach, or teach in the name (or by the power) of the Lord Jesus.

But Mr. Edwards (with whom I have here to deale) conceiving that the beauty of Christs true worship, would quickly discover the Foggy darkenesse of the Antichristian devised worship; and also that the glory of Christs true Discipline, grounded and founded in his Word, would soone discover the blacknesse and darkenesse of the Antihristian Government (which the poore people of England are in bondage unto) hath set his wits a work to withstand the bright comming of Christs Kingdome (into the hearts of men) which we are all commanded in the most absolute rule of Prayer to petition for; for the turning aside whereof Mr. Edwards hath mustred up his forces, even eight Reasons, against the government of Christ, which hee calls Independant; and hath joyned unto these eight, ten more; which he hath made against Toleration; affirming that they may not practise contrary to the course of the Nation wherein they live, without the leave of the Magistrate, neither judgeth he it commendable in them to aske the Magistrates leave, nor commendable in the Magistrate to heare their petitions, but rather seeketh to stirre up all men to disturbe their peace, affirming most unjustly, that they disturbe the peace of the Kingdome, nay, the peace of three Kingdomes, which all the lands under the Kings Dominions know to be contrary, nay I thinke most of the Kingdomes in Europe cannot be ignorant what the cause of the disturbance was;

But this is not the practise of Mr. Edwards alone, but also of the whole generation of the Clergie; as thou maist know, Christian Reader, to was the practise of the Bishop of Canterbury to exclaime against Mr. Burton, Doctor Bastwicke, and Mr. Prynne, calling them scandalous Libellers, & Innovators (though they put their own name to that which they write, and proved what they taught by divine authority) and this hath beene alwayes the practise of the instruments of Sathan, to accuse the Lords people, for disturbing of the peace, as it hath beene found in many Nations, when indeede the troublers be themselves and their fathers house. But in this they are like unto Athalia crying treason, treason, when they are in the treason themselves.

But for the further strengthning of his army, he hath also subjoyned unto these his Answer to fixe Reasons, which he saith, are theirs, but the forme of some of them seemeth to be of his owne making; all which thou shalt finde answered, and disproved in this following Treatise.

But though these my Answers are not laid downe in a Schollerlik way, but by the plaine truth of holy Scripture; yet I beseechthee have the patience to take the paynes to reade them, and spare some time to consider them; and if thou findest things disorderly placed, labour to rectifie them to thine own mind. And if there be any weight in them, give the glory to God; but if thou feest nothing worthy, attribute not the weakenesse thereof to the truth of the cause, but rather to the ignorance and unskilfulnesse of the weake Instrument.

Thine in the Lord Jesus,

Katherine Chidlet.

THE Answer to Mr. Edvvards his Introdvction.

I Hearing the complaints of many that were godly, against the Booke that Mr. Edwards hath written; and upon the sight of this his Introduction considering his desperate resolution, (namely) that he would set out severall Tractates against the whole way of Separation. I could not but declare by the testimony of the Scripture it selfe, that the way of Separation is the way of God, who is the author of it,* which manifestly appeares by his separating of his Church from the world, and the world from his Church in all ages.

When the Church was greater than the world, then the world was to be separated from the Church; but when the world was greater than the Church, then the Church was to separate from the world.

As for instance,

When Caine was a member of the Church, then the Church was greater than the world; and Caine being discovered, was exempted from Gods presence;* before whom he formerly had presented himselfe:c but in the time of Noah, when the world was greater than the Churchd then Noah and his Family who were the Church, were commanded to goe into the Arkee in which place they were saved, when the world was drowned,f yet Ham being afterward discovered, was accursed of his Father, and Shem was blessed, and good prophesied for Iaphat.

Afterward when the world was grown mightier than the Church againe, then Abraham was called out of Vr of the Caldeans, both from his country and from his kindred, and from his fathers houseg (because they were &illegible;) to worship God in Canaan.

Moreover, afterwards Moses was &illegible; and his brother &illegible; to deliver the children of Israel out of the Land of Egypt when Pharaoh vexed them,h at which time God wrought their deliverance,i separating wondrously between the Egyptians and the Israelites, and that which was light to the one, was darkenesse to the other.

Afterwards, when Corah and his Congregation rebelled against God, and were obstinate thereink the people were commanded to depart from the tenis of those &illegible; I &illegible; were the children separated from the parents, and those who did not separate, were destroyed by fire,lm and swallowed by the earth,n upon the day which God had appointed* as those Noahs time, who repented not, were swallowed by &illegible;.

Moreover, when God brought his people into the promised Land, he commanded them to be separated from the Idolatrous and not to meddle with the accursed things.Deut. 5. 26. 27. And for this cause God gave them his Ordinances and Commandements; and by the manifestation of their Obedience to them they were knowne to be the onely people of God,* which made a reall separation.

Ezza. 1. Hag. 1. 2, 3. 4. 8. 12. 14.And when they more carried captive into Babylon at any time for their sinnes: God raised them up deliverors to bring them from thence: and Prophets to call them from thencep and from their backesliding.q And it was the practise of all the Prophets of God, (which prophesied of the Church under the New Testament) to separate the precious from the vile, and God hath declared that bee that so doth shall be as his mouth, Jer. 15. 19.

And we know it was the practise of the Apostles of the Lord Iesus, to declare to the people that there could be no more agreement betweene beleevers and unbeleevers, than betweene light and darkenesse, God and Belial, as Paul writing to the Corinthians doth declare, when he saith, Be not unequally yoked together with unbeleevers; for what fellowship hath righteousnesse with unrighteousnesse? and what communion hath light with darkenesse, and what concord hath Christ with Belial?Christ made so great a difference betweene the world and the Church, that hee would not pray for the world; yet would die for the Church, which was given him out of the world; and without a Separation the Church can not be known from the world. or what part hath he that beleeveth with an Infidell? and what agreement hath the Temple of God with Idolls? for yee are the Temple of the living God, as God hath said, I will dwell in them, and walke in them, and I will be their God, and they shall be my people; Wherefore come out from among them, and be yet Separate, saith the Lord, and touch not the uncleane thing, and I will receive you, and I will be a Father unto you, and yee shall be my sonnes and daughters, saith the Lord Almighty, 1 Cor. 6. 14, 15, 16, 17, 18.

Moreover, they are pronounced blessed, which reade, heare, and keepe the words of the Booke of the Revelation of Iesus Christ;r among which sentences, there is a commandement from heaven for a totall Separation.s

These things (in briefe) I have minded from the Scriptures, to prove the necessitie of Separation; and though the Scripture be a deepe Well, and containeth in the Treasures thereof innumerable Doctrines and Precepts tending to this purpose; yet I leave the further prosecution of the same, till a fitter opertunity be offered to me, or any other whom the Lord shall indue with a greater measure of his Spirit.

But Mr. Edwards, for preparation to this his desperate intention, hath sent these Reasons against Independant government, and Toleration, and presented them to the Honorable House of Commons; which Reasons (I thinke) he would have to beget a Snake, to appeare (as he saith) under the greene grasse; for I am sure, he cannot make the humble petitions of of the Kings subjects to be a Snake, for petitioning is away of peace and submission, without violence or venum; neither can it cast durt upon any government of the Nation, as he unjustly accuseth the Protestation Protested, for that Author leaveth it to the Magistrate, not undertaking to determine of himselfe what government shall be set ever the Nation, for the bringing of men to God but leaveth it to the consideration of them that have authority.

And whereas Mr. Edwards grudges that they preach so often at the Parliament; in this he is like unto Amazial, who bid the Prophet Amos to flee away into the Land of Judea. and not to Prophesie at Bethel, the Kings Chappeil, and the House of the Kingdome.*

And though Mr. Edwards boast himselfe heare, to be a Minister of the Gospell, and a sufferer for it, yet I challenge him, to prove unto me, that he hath any Calling or, Ordination to the Ministry, but that which he hath successively from Rome; If he lay claime to that; he is one of the Popes household; But if he deny that calling, then is he as void of a calling to the worke of the Ministry, and as void of Ordination, as any of those Ministers, whom hee calleth Independant men, (which have cust off the Ordination of the Prelates) and consequently as void of Ordination as a macanicall trades man.

And therefore I hope that Honourable House that is so full of wisedome (which Mr Edwards doth confesse) will never judge these men unreasonable, because they do Petition, nor their petitions unreasonable before they are tried, and so proved, by some better ground, then the bare entrance of Mr. Edwards his Cavit, or writ of Ne admittas, though he saith he forehed it from heaven; for I know it was never there, Neither is it confirmed by the Records of holy Scripture, but taken from the practise of Nimrod. That mighty Hunter before the Lord,* and from the practise of Haman that wicked persecucuter,* & from the evill behaviour and malicious speeches, and gesture of wicked Sanballet,* and Tobias, who were both bitter enemies to God, and sought to hinder the building of the walles of Jerusalem.

But the Prophet Haggai, reproveth not onely such as hindred the building of the Lords House: but also those that were contented to live in their seyled Houses, and suffer the Lords House to lie waste, Hag. 1.

AN ANSVVER To Mr. Edvvards his Booke, Intituled, Reasons against the Independent Government in particular Congregations.

Mr. EDWARDS,

I Understanding that you are a mighty Champion, and now mustering up yourmighty forces (as you say) and I apprehending, they must come against the Hoast of Israel, and hearing the Armies of the Living God so defied by you, could nor be withheld, but that I (in stead of a better) must needs give you the meeting.

First, Whereas you affirme, That the Church of God (which is his House and Kingdome) could not subsist with such provision as their father gave them: which provision was (by your owne confession) the watering of them by Evangelists, and Prophets, when they were planted by the apostles, and after planting and watering to have Pastors and Teachers, with all other Officers, set over them by the Apostles & their own Election, yet notwithstanding all this provision, the Father hath made for them, it was evident (say you) they could not well stand of themselves, without some other helpe.

This was the very suggestion of Sathan into the hearts of our first Parents; for they having a desire of some thing more then was warranted by God, tooke unto them the forbidden fruit, as you would have the Lords Churches to doe when you say they must take some others besides these Churches and Officers, and that to interpose authoritatively; and these something else you make to be Apostles, Evangelists, and Elders of other Churches, whereas you confessed before, that these are the furniture of Christs Kingdome; and wee know their authoritie was limitted, within the bounds of the Word of God: as first, If any of them would be greater, he must be servant to all. Secondly, they were forbidden to be Lords over Gods heritage. Thirdly, they were commanded to teach the people, to observe onely those things which Christ had commanded them.

And whereas you seeme to affirme, that these Offices were extraordinary and ceased, and yet the Churches have still neede of them: You seeme to contradict your selfe, and would faine cure it againe, in that some other way which you say, you have to supply the want of them, but this other way you have not yet made known: You presuppose, it may be by some Smods and Councels, to make a conjunction of the whole.

If you meane such a Counsell, as is mentioned; Acts 15. 4. 22. consisting of Apostles and Elders with the whole Church; then you have said no more than you have said before, and that which we grant, for this is still the furniture of the Kingdome; but if you intend that your Counsell should consist of an armie of Arch-Bishops Diocesan Bishops, Deanes, Suffragans, with the rest of that rabble, which be for their titles names of blasphemy, and such as were bred in the smoake of the pit. I deny that any of these be ordained of God, for they have no footing in his word; therefore indeede these are a part of the fruit of the forbidden Tree, which the Churches of God have taken and eaten; and this seeking out inventions of their owne, after that God made them righteous, hath brought them into a state of Apostasie, even as Ieroboams high places and Calves did the people of Israel; which may plainely appeare by the Churches of Asia. If these be that some other supply which you meane and have produced to helpe the Churches, and Cities of God (as you call them) to determine for those Churches and Cities the cases of Doctrine and Discipline in stead of those many Ministers which, you conceive them now to want, it tends to make (as they have now done) a conjunction not onely of all the Churches prosessing one faith into one body; but also of all the Armies of the Man of Sinne, and so to confound the Church and the world together, which the Ministers of the Gospell ought to divide,Iss. 15. 19. by separating the precious from the vile.

And whereas you affirme, The Independent Congregations now have but few Ministers;

It is very true, for indeede they are but a few people, and a few hands will feede a few mouths sufficiently, if God provide meat.

But whereas you affirme, That those Congregations may have no Officer, at all by their owne grounds, and yet be independent.

I thinke, they conceive by those grounds, the Office onely of Pastor, and Teacher; but not that the Church of God hath need at any time of the helpe of any other, then God hath given and set in his Church, which be all the Officers that are before mentioned, as Apostles, Prophets, Evangelists, Pastors, and Teachers; and to have recourse to any for counsell, helpe, or assistance, either of Church or Ministry, which is not of Christs owne, were very ridiculous. For it is recorded, Ephe. 4. 11. 12. That he gave these for the gathering together of the Saints for the worke of the Ministry, and for the edification of the body of Christ, being so gathered;Verse 13. 14. 16. The time they must continue is, till all the Saints be in the unitie of faith. The reason wherefore they were given, was to keepe people from being tossed too and fro with every winde of Doctrine. And these are they, by whom all the body is coupled and knit together,Compared with 1 Cor. 12. by every joynt for the furniture thereof, according to the effectuall power, which is in the measure of every part, and receiveth increase of the body unto the edifying of it selfe in love. And this is according to the promise that Christ made, Matth. 28. 19. 20. to be with his Ministers in teaching his people to the end of the world.

And thus you may see Mr. Edwards, you cannot gather from our owne words, that we have neede of the helpe of any other Churches, or Ministers, to interpose (as you unjustly affirme) as it may plainely appeare by Mr. Robinsons owne words in the Justification of the Separation, pag. 121. 122. These are his words; It is the Stewards duty to make provision for the family; but what if he neglect this duty in the Masters absence? Must the whole family starve, yea and the wife also? Or is not some other of the family best able to be employed for the present necessity? The like he saith concerning the government of a Ship, of an Armie, and of Commonwealths; alluding to the Church of Christ. And further expresseth, that as a private Citizen may become a Magistrate, so a private member may become a Minister, for an action of necessity to be performed, by the consent of the rest, &c.

Therefore it appeares plainely by all that hath binsaid, that the Churches of Christ may be truely constituted according to the Scripture, and subsist a certaine time without Pastor and Teacher, and enjoy the power of Christ amongst themselves having no dependancie upon any other Church or Churches which shall claime Authority or superiority over them.

And thus much for your first Reason.

NOw in your second Reason, which runneth upon the calling of the Ministry, you affirme, That the government of the Independent Congregations is not of divine institution.

Which I utterly denie, and will prove it, by disproveing the following. Instances, by which you affirme to prove it.

Whereas you affirme, That their Independencie forces them to have Ministers without Ordination.

I Answer, it is a plaine case by the foregoing Answer, to your first Reason, that you speake untruely, for their practise is there made knowne to be otherwise; and if you will still affirme, that they have not power so to practise, you will thereby deny the truth of the Scriptures; for the Apostles were commanded to teach the Churches, to observe all things whatsoever Christ had commanded them. But Christ commanded the Apostles to ordaine Elders in every Church by election; therefore the Apostles taught the Churches to ordaine Elders by Election also. And whereas you bid us produce one instance (if we can) for an ordinary Officer to be made without Ordination, it is needlesse; for we (whom you call Independant) strive for no such thing, as you have proved it plainely out of Mr. Robinsons Booke, Apol. Chap. 1. 18. to which I send you to learne better.

Further you alleadge, That if they be ordained, it is by persons who are not in office.

Now if you meane, they have no office because they are not elected, ordained and set apart by the Clergie to some serviceable, administration; I pray you tell me who ordained the Apostles, Prophets, and Evangelists to their worke or Ministry? If you will say they were ordained of God, I will grant it, and doe also affirme that God hath promised the supply of them, to the end of the world, as before hath beene mentioned, from Ephe. 4. As a so, it appeares by Pauls charge to Timothy; 2 Tim. 2. 2. That what things he had heard of him, among many witnesses, the same he should commit to faithfull men who should be able to teach others also: but I verily doe beleeve, that as Titus, so Timoth, heard of Paul that Elders must be ordained by Election in every city, and that Titus was as much bound to communicate the things unto others, which he had learned of Paul, as Timothy was, and Timothy (we know) was to teach faithfull men, and those faithfull men were to teach others those things that they had heard of Timothy, among which things Ordination was one, as it was delivered to Titus; and we are not to doubt of Timothius faithfulnesse in the declaring of this part of his message more than the rest, but if those to whom Timothy delivered it, were not faithfull in the discharge of their duty: but that in due time the Ordinances might possibly grow out of use, as the Churches did by little and little apostate; yet that hinders not but that it was still written in the Scripture that the generations to come might recover againe the right use of the Ordinances when God should by his Spirit direct them to know the same.

Moreover, I affirme, that all the Lords people, that are made Kings and Priests to God, have a free voyce in the Ordinance of Election, therefore they must freely consent before there can be any Ordination; and having so consented they may proceede to Ordination, notwithstanding they be destitute, of the Counsell or assistance of any neighbour Church; as if there were no other Churches in the Land, but onely one company of beleevers joyned together in fellowship, according to Christs institution. The promise made in the 14th, of Iohn 12. 13. is made unto them, where Christ said. The workes that he did they should doe &illegible; & that whatsoever they should aske in his name, that he would do for &illegible; that the Father may be glorified, and that the Spirit of truth should dide with them for ever. And that he should teach them all things, and bring all things unto their remembrance, as it is said in the following verses of the same Chapter. This (you may see) is the portion of beleevers, and they that have this portion are the greatest in the world, and many of them are greater than one, but many joyned together in a comely order in the fellowship of the Gospell, according to the Scriptures, are the greatest of all and therefore have power to ordaine, and to blesse their Ministers in the name of the Lord. Thus the lesser is blessed of the greater.

Now Mr. Edwards, I hope you will confesse, that you spake unadvisedly, when you affirmed, The maintenance of Independensie, was the breaking of Gods Ordinance, and violating of that Order and constant way of Ministers recorded in the Word.

To this I Answer, that if the Church doe elect one, he must be elected out of some more, & those that are not elected, may be as able to blesse the Church in the name of the Lord, as he, therefore one of these who are not elected, being chosen by the whole Church, to blesse him in the name of the Lord, whom the Church hath ordained, is the hand of the whole (who are greatest of all, and so a sufficient Officer for that worke which hee is put a part to doe.

Thus you may see (Mr. Edwards) that we doe not hold Ordination extraordinary and temporary; neither doe we hold it the least of Gods Institutions, for we have respect unto them all; But that nothing in matter of Order hath so cleare and constant a practise as this (as you do affirme) and also say, the whole frame of Church and Discipline, hath not so much ground in the word for it as this. I deny, and doe affirme, that not onely this, but all Gods Ordinances have as much ground and footing in Gods Word also.

Yet notwithstanding you say, that Calvin confesseth, that there is no expresse precept concerning the imposition of hands: Hath the imposition of hands no footing in Gods Word? and yet hath not all the forme of Gods Worship so much footing as it? Here Mr. Calvin and you, will now pin all the forme of Church and Discipline, upon unwritten verities.

Further, you rehearse confusedly, the opinion of Zanchius to strenghen yours who (say you) would have the example of the Apostles and ancient Church, to be more esteemed of, and to be instead of a command.

I pray you, how doe you know it to be their example, if it be not written?

And whereas you alledge, that Zanchius saith, it is no value Ceremony but the holy Spirit is present to performe things inwardly, which are signified by this Ordinance outwardly.