Tracts on Liberty by the Levellers and their Critics Vol. 6 (1649)

1st Edition, uncorrected (Date added: March 18, 2015)

This volume is part of a set of 7 volumes of Leveller Tracts: Tracts on Liberty by the Levellers and their Critics (1638-1659), 7 vols. Edited by David M. Hart and Ross Kenyon (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2014). </titles/2595>.

It is an uncorrected HTML version which has been put online as a temporary measure until all the corrections have been made to the XML files which can be found [here](/titles/2595). The collection will contain over 250 pamphlets.

- Vol. 1 (1638-1843): 11 titles with 1,562 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-1>

- Vol. 2 (1644-1645): 12 titles with 564 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-2>

- Vol. 3 (1646): 22 titles with 854 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-3>

- Vol. 4 (1647): 18 titles with 2,011 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-4>

- Vol. 5 (1648): 30 titles with 1,078 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-5>

- Vol. 6 (1649): 27 titles with 277 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-6>

- Vol. 7 (1650-1660): 42 titles with 1,055 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-7>

- Addendum Vol. 8 (1638-1646): 33 titles with 1,858 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-8>

- Addendum Vol. 9 (1647-1649): 47 titles with 2,317 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-9>

To date, the following volumes have been corrected:

- Vol. 1 (1638-1643) </titles/2597>

- Vol. 2 (1644-1645) </titles/2598>

- Vol. 3 (1646) </titles/2596>

Further information about the collection can be found here:

- Introduction to the Collection

- Titles listed by Author

- Combined Table of Contents (by volume and year)

- Bibliography

- Groups: The Levellers

- Topic: the English Revolution

2nd Revised Edition

A second revised edition of the collection is planned after the conversion of the texts has been completed. It will include an image of the title page of the original pamphlet, its location, date, and id number in the Thomason Collection catalog, a brief bio of the author, and a brief description of the contents of the pamphlet. Also, the titles from the addendum volumes will be merged into their relevant volumes by date of publication.

Tracts on Liberty by the Levellers and their Critics, Volume 6 (1649) (1st edition, uncorrected)

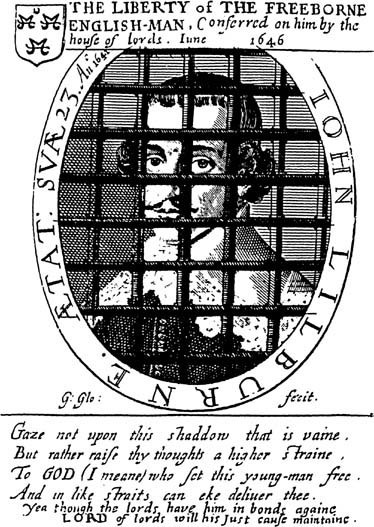

The Liberty of the Freeborne English-Man, Conferred on him by the house of lords. June 1646. John Lilburne. His age 23. Year 1641. Made by G. Glo.

“Gaze not upon this shaddow that is vaine,

Bur rather raise thy thoughts a higher straine,

To GOD (I meane) who set this young-man free,

And in like straits can eke thee.

Yea though the lords have him in bonds againe

LORD of lords will his just cause maintaine.”

Table of Contents

- Editor’s Introduction to Volume 6 (1649)

- Publishing and Biographical Information

- Copyright and Fair Use Statement

- Tracts from Volume 6 (1649) (277 illegibles)

- 6.1. [Anon.], The humble Petition of firm and constant Friends to the Parliament (n.p., 19 January 1649).

- 6.2. John Rushworth, A Petition concerning the Draught of an Agreement of the People (London: John Partridge, 20 January 1649).

- 6.3. John Lilburne, Englands New Chains Discovered (n.p., 26 February 1649).

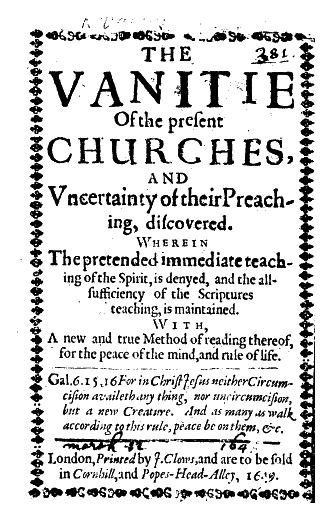

- 6.4. [William Walwyn], The Vanitie of the present Churches (London: J. Clows, 12 March 1649).

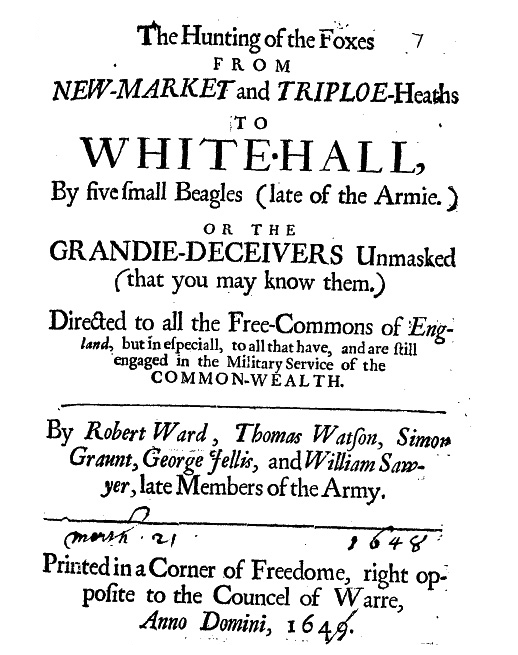

- 6.5. [Signed by Robert Ward, Thomas Watfon, Simon Graunt, George Jellis, William Sawyer (or 5 “Beagles”), but attributed to Richard Overton or John Lilburne], The Hunting of the Foxes (n.p., 21 March 1649).

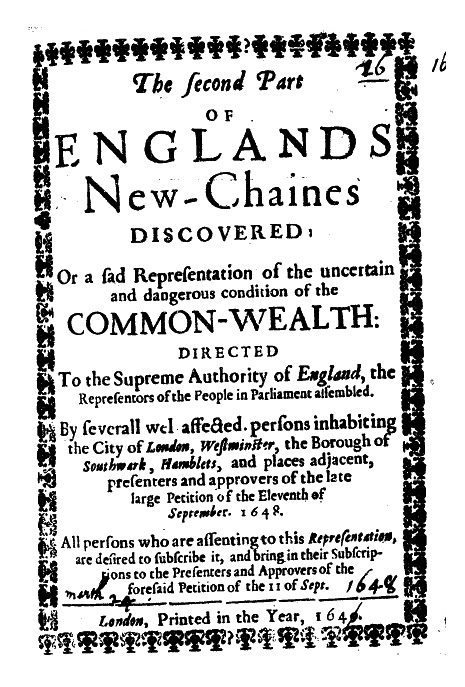

- 6.6. [John Lilburne], The Second Part of Englands New-Chaines Discovered (London, n.p., 24 March 1649).

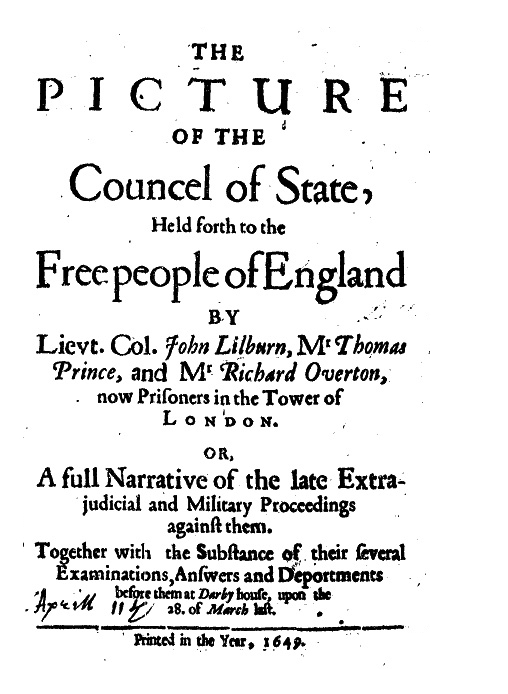

- 6.7. John Lilburne, Thomas Prince, Richard Overton, The Picture of the Councel of State (n.p., 4 April, 1649).

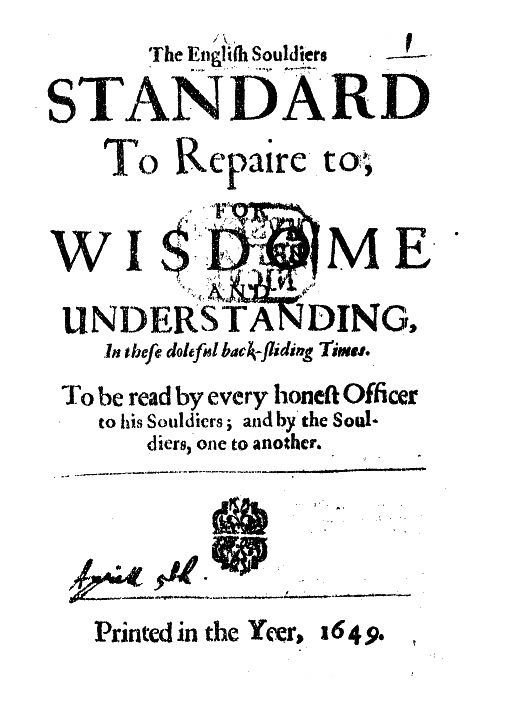

- 6.8. [William Walwyn], The English Souldiers Standard (n.p., 5 April 1649).

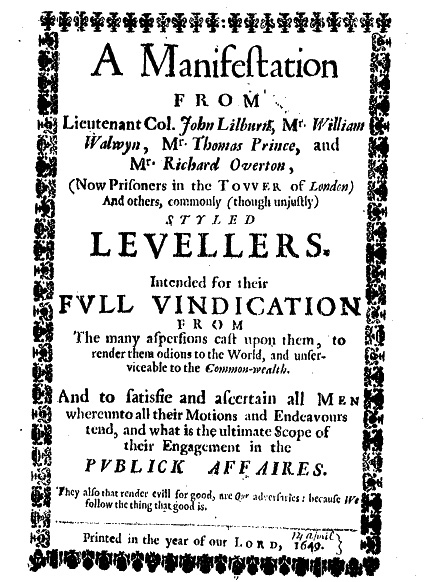

- 6.9. [Signed by John Lilburn, William Walwyn, Thomas Price, Richard Overton, sometimes attributed mainly to Walwyn], A Manifestation from Lieutenant Col. John Lilburn et al. (n.p., 14 April 1649).

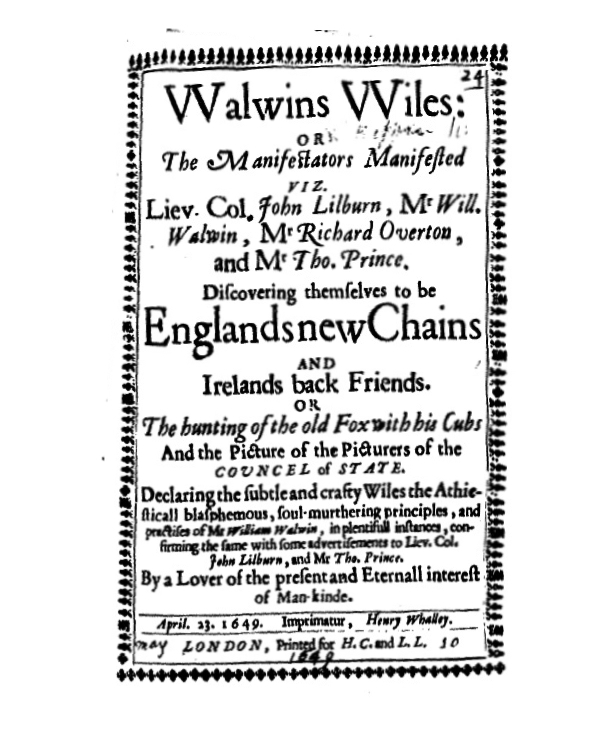

- 6.10. [John Prince], Walwyns Wiles: Or The manifesters Manifested (London: Henry Whalley, 23 April 1649).

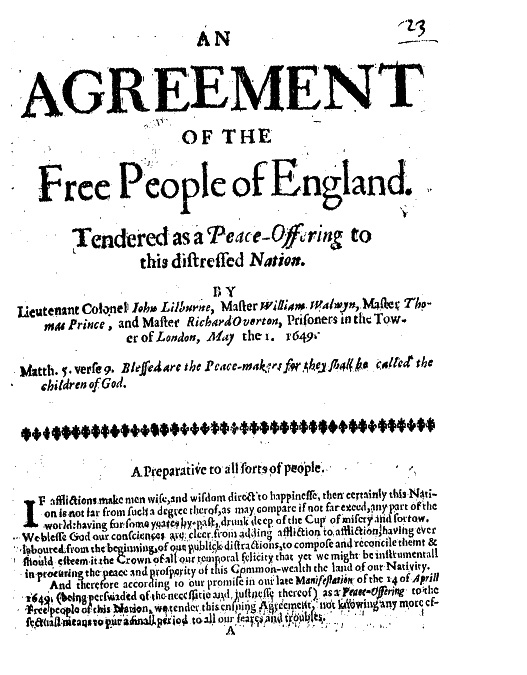

- 6.11. John Lilburne, William Walwyn, Thomas Prince, Richard Overton, An Agreement of the Free People of England (London: Gyles Calvert, 1 May 1649).

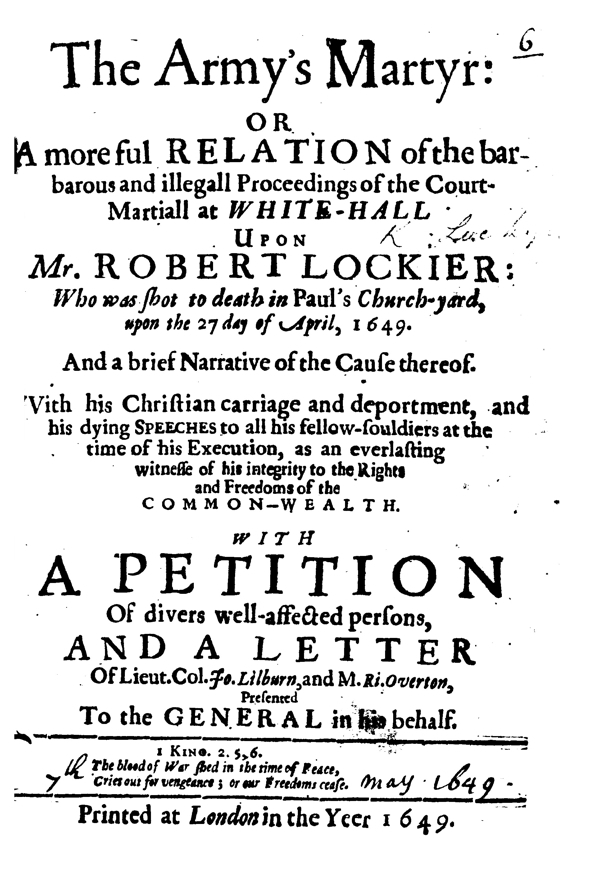

- 6.12. Robert Lockier, John Lilburne, and Richard Overton, The Army’s Martyr (London, n.p., 4 May 1649). [5 illegibles]

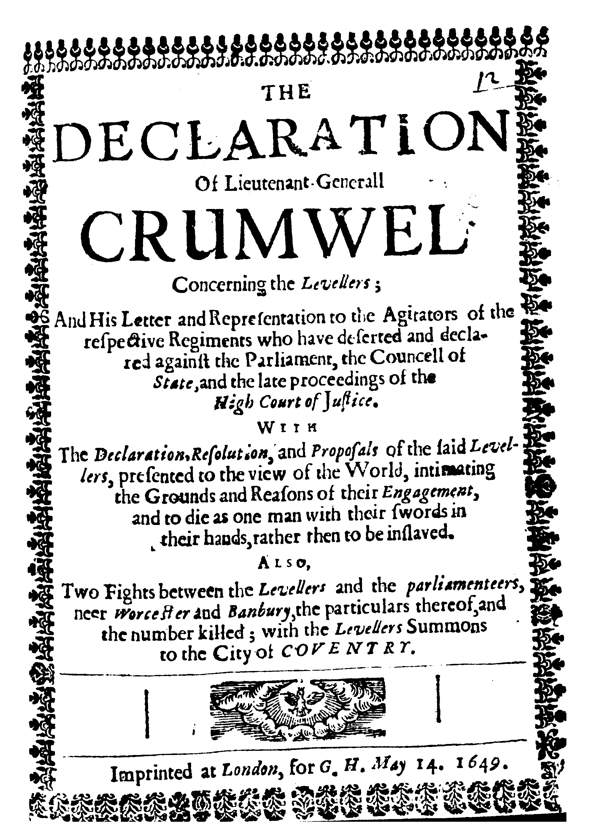

- 6.13. Oliver Cromwell, The Declaration of Lieutenant Generall Crumwel Concerning the Levellers (London, n.p., 14 May 1649). [2 illegibles]

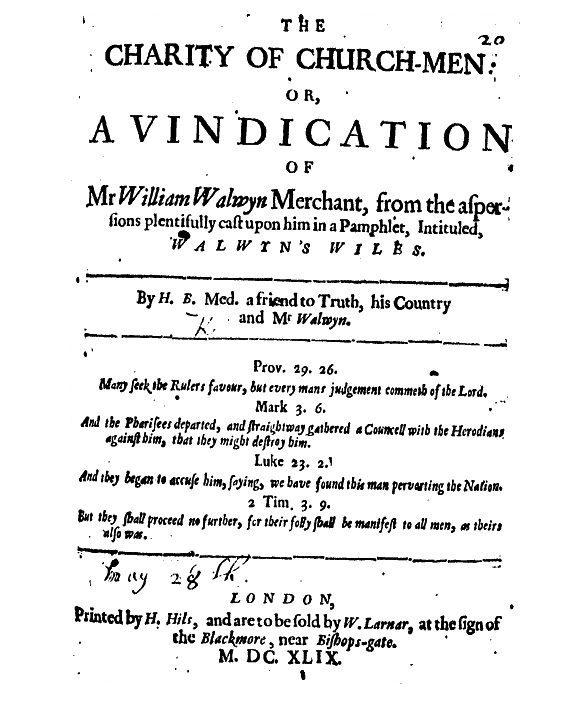

- 6.14. [Humphrey Brooke], The Charity of Church-men (n.p., 28 May 1649).

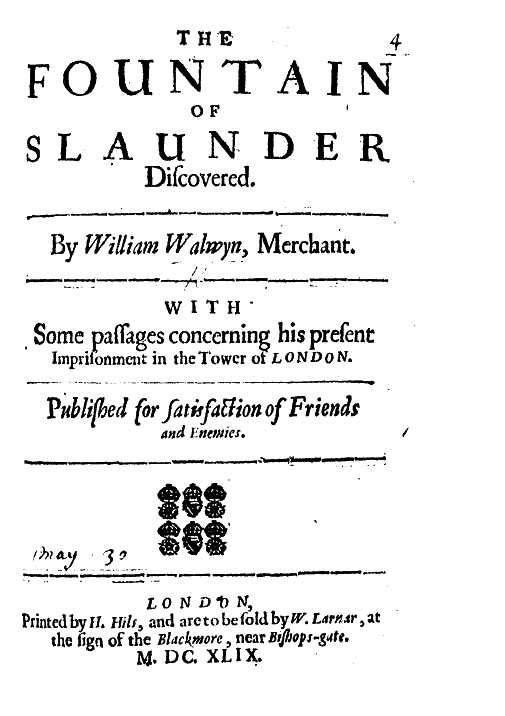

- 6.15. William Walwyn, The Fountain of Slaunder Discovered (London: H. Hills, 30 May 1649).

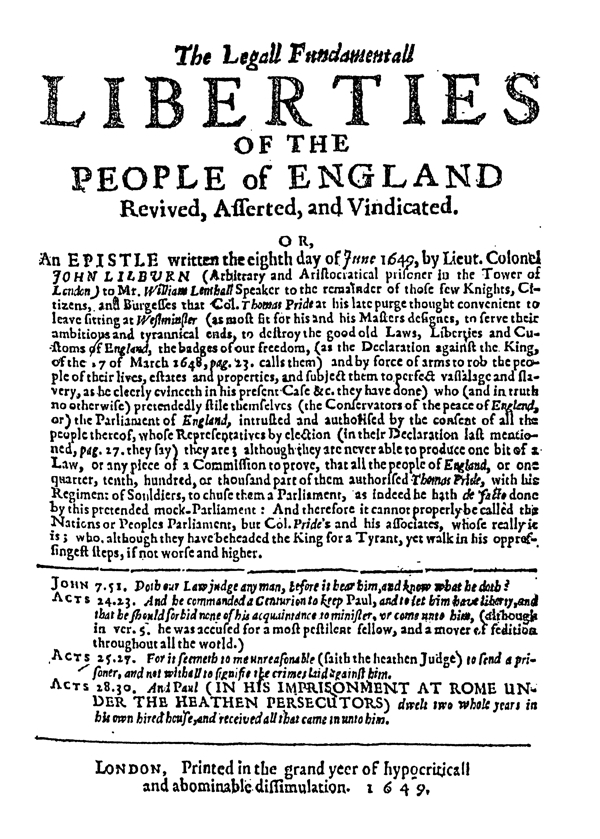

- 6.16. John Lilburne, The Legall Fundamentall Liberties of the People of England Revived, Asserted, and Vindicated (London, n.p., 8 June 1649). [148 illegibles]

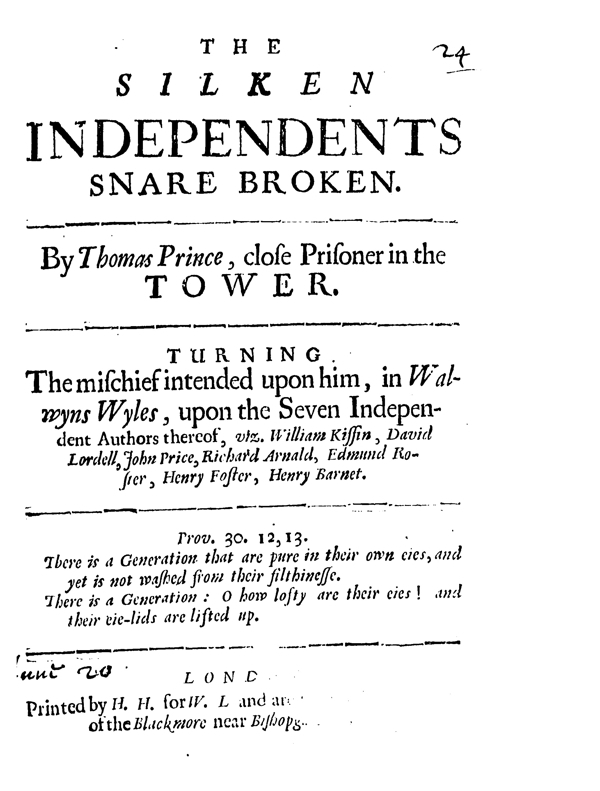

- 6.17. Thomas Prince, The Silken Independents Snare Broken (London, n.p., 20 June 1649). [2 illegibles]

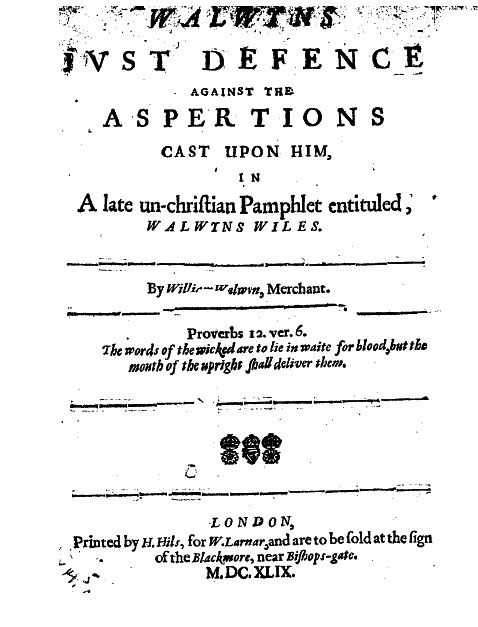

- 6.18. William Walwyn, Walwyns Just Defence (London: H. Hils, June/July 1649).

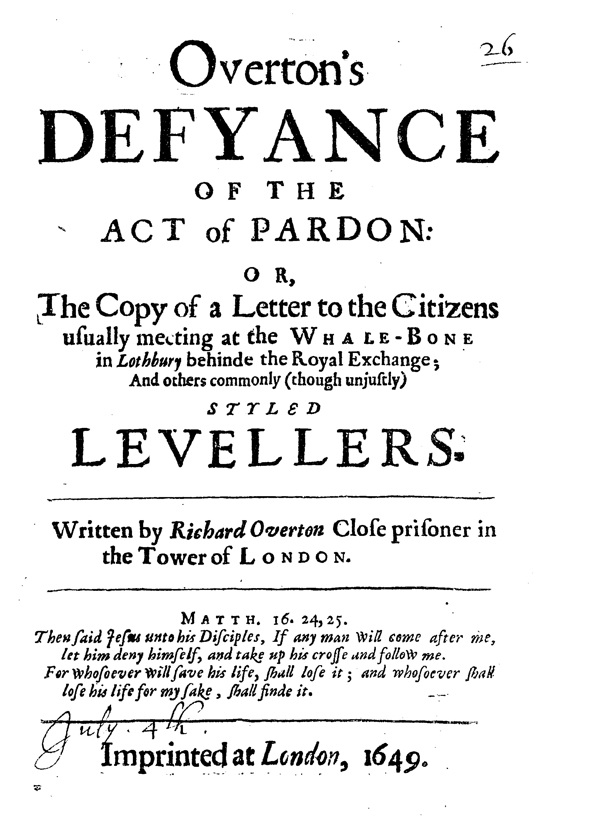

- 6.19. Ricard Overton, Overton’s Defyance of the Act of Pardon (London, n.p., 2 July 1649). [23 illegibles]

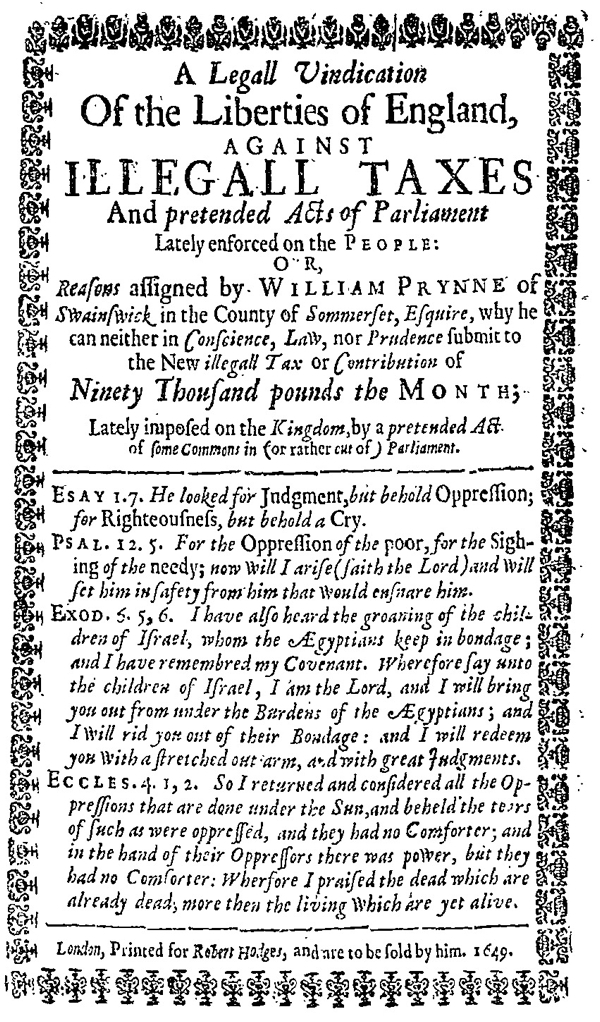

- 6.20. William Prynne, A Legall Vindication Of the Liberties of England (London, n.p., 16 July 1649). [51 illegibles]

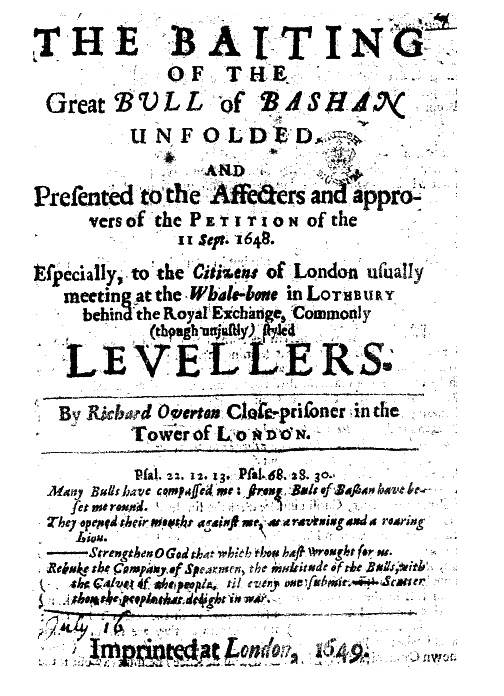

- 6.21. Richard Overton, The Baiting of the Great Bull of Bashan (London, n.p., 16 July 1649).

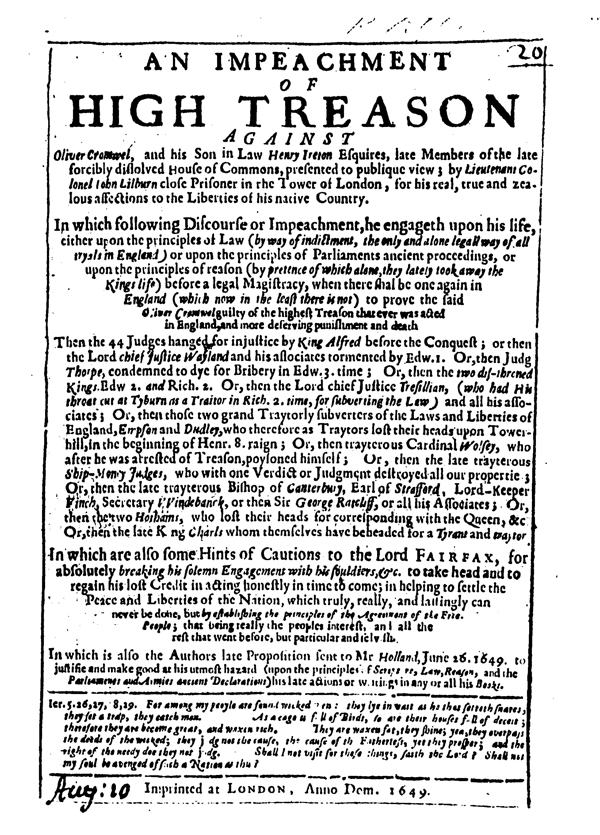

- 6.22. John Lilburne, An Impeachment of High Treason against Oliver Cromwel, and his Son in Law Henry Ireton Esquires (London, n.p., 10 August 1649). [46 illegibles]

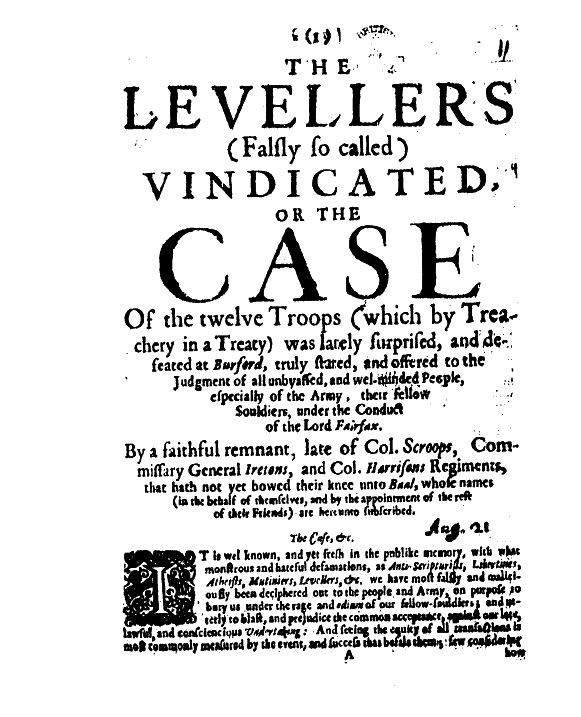

- 6.23. Six Soldiers (John Wood, Robert Everard, Hugh Hurst, Humphrey Marston, William Hutchinson, James Carpe), The Levellers (falsely so called) Vindicated (n.p., 20 August 1649).

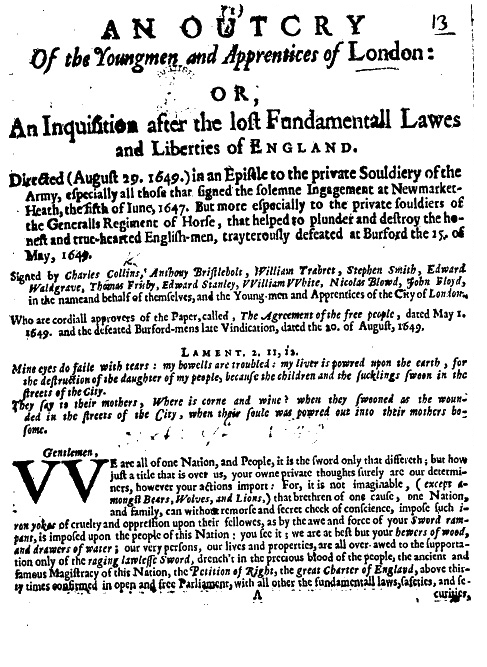

- 6.24. [Signed by several but attributed to John Lilburne], An Outcry of the Youngmen and Apprentices of London (n.p., 29 August 1649).

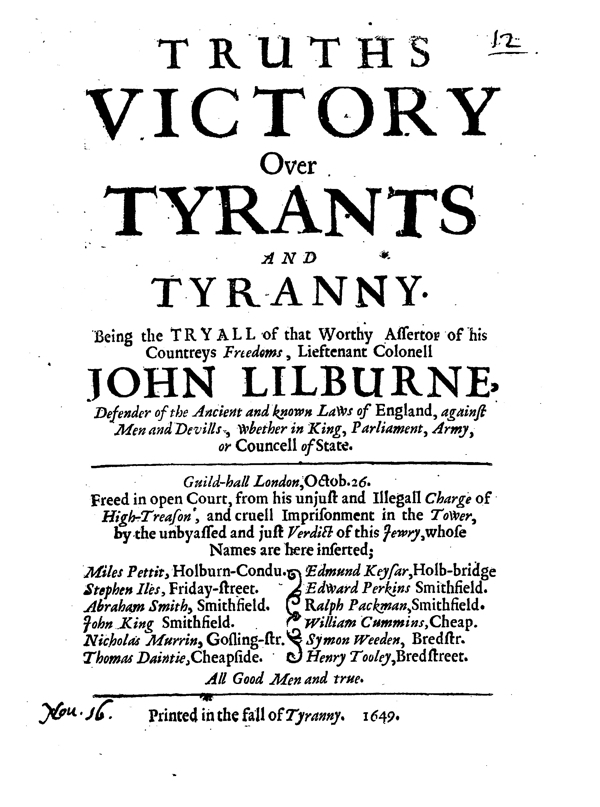

- 6.25. John Lilburne, Truths Victory over Tyrants and Tyranny (n.p., 16 November 1649).

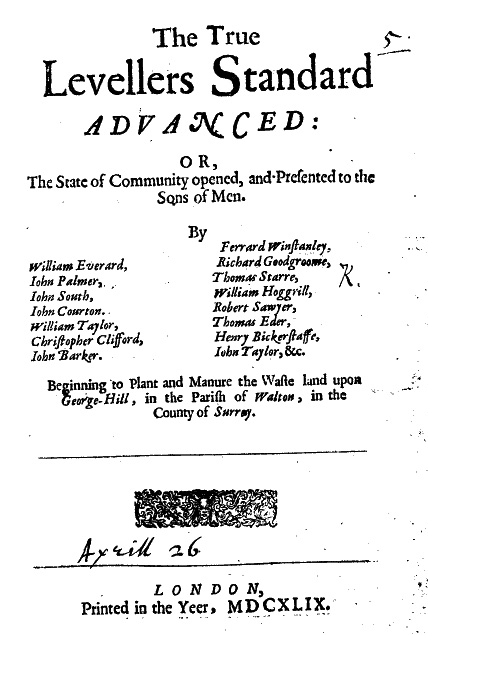

- 6.26. Gerrard Winstanley et al., The True Levellers Standard Advanced (London, n.p., 1649).

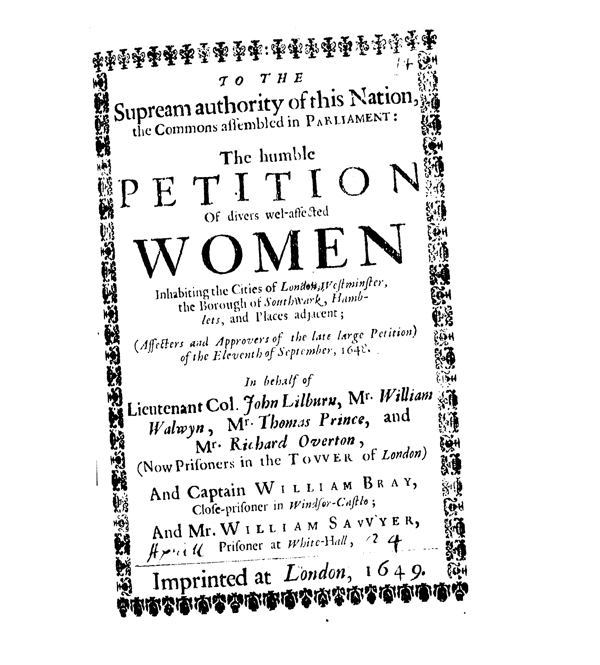

- 6.27. Anon., The humble Petition of divers wel-affected Women (London, n.p., 1649).

Editor’s Introduction to Volume 6 (1649)↩

[to be added later]

Publishing and Biographical Information

Publishing information about each title can be found in the catalog of the George Thomason collection (henceforth "TT" for Thomason Tracts). Each tract is given a catalog number and a date when the item came into his possession (thus not necessarily the date of publication). We have used these dates to organise our collection in rough chronological order:

Catalogue of the Pamphlets, Books, Newspapers, and Manuscripts relating to the Civil War, the Commonwealth, and Restoration, collected by George Thomason, 1640-1661. 2 vols. (London: William Cowper and Sons, 1908).

- Vol. 1. Catalogue of the Collection, 1640-1652 [PDF

only] .

- Vol. 2. Catalogue of the Collection, 1653-1661. Newspapers. Index. [PDF only]

Biographical information about the authors can be found in the Biographical Dictionary of British Radicals in the Seventeenth Century, ed. Richard L. Greaves and Robert Zeller (Brighton, Sussex: The Harvester Press, 1982-84), 3 vols.

- Volume I: A-F

- Volume II: G-O

- Volume III: P-Z

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

The texts are in the public domain.

This material is put online to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. Unless otherwise stated in the Copyright Information section above, this material may be used freely for educational and academic purposes. It may not be used in any way for profit.

Tracts from Volume 6 (1649)

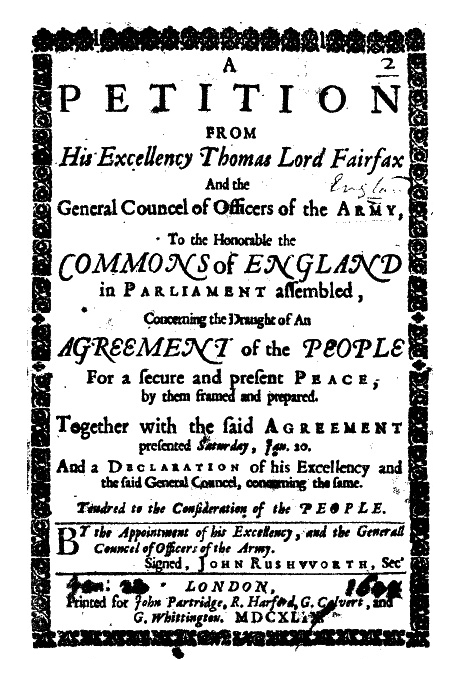

6.1. [Anon.], The humble Petition of firm and constant Friends to the Parliament (n.p., 19 January 1649).↩

Bibliographical Information

Full title[Anon.,] To the Right Honourable, the Supreme Authority of this Nation, the Commons of England in Parliament assembled. The humble Petition of firm and constant Friends to the Parliament and Common-wealth, Presenters and Promoters of the Large Petition of September 11. MDCXLVIII.

Estimated date of publication18 January 1649.

Thomason Tracts Catalog informationTT1, p. 715; Thomason 669. f. 13 (73.)

Editor’s Introduction

(Placeholder: Text will be added later.)

Text of Pamphlet

Sheweth,

That having seriously considered how many large and fair opportunities this honourable House hath had within these eight yeers last past to have made this Nation absolute free and happy; and yet that until this time, every of those opportunies have (after some short space of hope) faded, and but altered, if not increased our bondage.

When we call to mind what extraordinary things the Army undertook (and this honourable House approved) in behalf of the liberties of the people, in the yeer 1647 and that nevertheless, the first fruits of their great and unexpected success, was a more oppressive Ordinance for enforcing of Tyths, than ever had bin before, and which hath bin severely executed, and is still continued, to the extreme vexation of Friends, and encouragement of Pulpit Incendiaries; And how that great and wonderful opportunities wasted it self away in contending with, and imprisoning of cordial Friends, or in tampering with known enemies, and at length ended in a most dangerous and bloudy war; whereas rightly applied, it might have given peace and security to the Nation for many Generations.

These things considered, although we exceedingly rejoyced in your just and excellent Votes of the 4 of this instant Ianuary, as a people who had long suffered the reproches of Sectaries & Levellers, for maintaining the supreme original of all just power to be in the people, & the supreme Authority of this Nation to be in this honourable House, (which our burnt Petitions, and that of Sept. 11. do fully witness. Yet since we understand, that within few daies after you admitted a message from the House of Lords, and gave an accustomed respect thereunto. We have bin very much troubled, how already the same doth essentially derogate from your foresaid Votes.

And since also, we have seen a printed Warrant of his Excellency the Lord General Fairfax, directed to his Marshal General, for suppressing of unlicensed Books and Pamphlets, authorising him (upon the oath of one witness) to take all persons offending into custody, and inflict upon them such corporal punishments, and levie such fines upon them, as your Ordinances impose; and not to discharge them, until after payment and punishment; And further, to make diligent search in all places where the said Marshal shall think meet, for unlicensed printing presses, employed in printing scandalous, unlicensed pamphlets. Books, See. and to seise and carry away such printing presses, fee. And likewise to make diligent search in all suspected printing houses, ware-houses, and other shops and places whatsoever, for such unlicensed books, &c. And in case of opposition, to break open (according to your Ordinances) all dores and locks, and to apprehend all persons so opposing and take them into custody, till they have given satisfaction therein. And all this by vertue of an order of yours of the fift of this instant Ianuary. Since we have seen this, we profess, we cannot but already fear the issue and consequence of those excellent Votes, nothing more dangerous to a people, than the mis-application of their supreme entrusted Authority; and therefore we entreat herein to be excused, though we appear herein, as in a cause of very great Importance.

For what-ever specious pretences of good to the Common-wealth have bin devised to over-aw the Press, yet all times tore-gone will manifest, it hath ever ushered in a tyrannie; mens mouth being to be kept from making noise, whilst they are robd of their liberties; So was it in the late Prerogative times before this Parliament, whilst upon pretence of care of the publike. Licensers were set over the Press, Truth was suppressed, the people thereby kept ignorant, and fitted only to serve the unjust ends of Tyrants and Oppressors, whereby the Nation was enslaved; Nor did any thing beget those oppressions so much opposition, as unlicensed Books and Pamphlets.

A short time after the begining of this Parliament, upon pretense of publike good, and at the solicitation of the Company of Stationers (who in all times have bur officiously instrumental unto Tyrannic) the Press again (notwithstanding the good service it immediately before had done) was most ungratefully committed to the custody of Licensers, when though scandalous Books from or in behalf of the Enemy then at Oxford was the pretended occasion; yet the first that suffered was M. Lawrence Sanders, for Printing without license, a book intituled, Gods Love to Mankind; and not long after, M. John Lilburn, M. William Larnar, and M. Richard Overton, and others, about books discovering the then approching Tyrannie; whilst scandalous Pamphlets nevertheless abounded, and did the greater mischief, in that Licensers have never bin so free to pass, as good men have bin forward to compile proper and effectual answers to such books and pamphlets: And whether Tyrannic did soon follow thereupon, the courses you were forced unto in opposition, and the necessities you were put upon for your preservation, will most cleerly demonstrate. And if you, and your Army shall be pleased to look a little back upon affairs, you will find you have bin very much strengthened all along by unlicensed Printing; yea, that it hath done (with greatest danger to the doers) what it could to preserve you, when licensed did its utmost to destroy you; and we are very confident, those very excellent and necessary Votes of yours fore-mentioned, had made you a multitude of enemies, if unlicensed printing had not prepared and smoothed your way for them, whereas now they are received with great content and satisfaction.

And generally, as to the whole course of printing, as justly in our apprehensions, may Licensers be put over all publike or private Teachings, and Discourses, in Divine, Moral, Natural, Civil, or Political things, as over the Press; the liberty whereof appears so essential unto Freedom, as that without it, its impossible to preserve any Nation from being liable to the worst of bondage; for what may not be done, to that people who may not speak or write, but at the pleasure of Licensers?

As for any prejudice to Government thereby, if Government be just in its Constitution, and equal in its distributions, it will be good, if not absolutely necessary for them, to hear all voices and judgements, which they can never do, but by giving freedom to the Press; and in case any abuse their authority by scandalous Pamphlets, they will never want able Advocates to vindicate their innocency. And therefore all things being duely weighed, to refer all Books and Pamphlets to the judgement, discretion, or affection of Licensers, or to put the least restraint upon the Press, seems altogether inconsistent with the good of the Commonwealth, and expresly opposite and dangerous to the liberties of the people, and to be carefully avoided, as any other exorbitancy or prejudice in Government.

And being so, we beseech you to consider how unreasonable it is for every man or woman to be liable to punishment, penal or corporal, upon one witness in matters of this Nature, for compiling, printing, selling or dispersing of Books and Pamphlets, nay to deserve even whipping (as the last ycers Ordinance, an Engine fited to a Personal Treaty) doth provide a punishment, as we humbly conceive, fit only for slaves or bondmen. But that this honourable House, that is now by an extraordinary means freed from that major part, (which degenerating from the true Interest of the people, were the unhappy authors of that Ordinance) and reduced to that minor part, which we alwaies hoped did really oppose the same, should now approve thereof, and of all other Ordinances of like nature; and not oncly so, but in cases so meerly Civil, to refer the execution thereof to a Military power: This is that which in the present sense and consequence thereof, afflicts us above measure; because according to this rule, we may we know not how soon, be reduced under a military jurisdiction, which we humbly conceive, we ought not to be, and which above any thing in this world, we shall desire in this and all other cases for ever to avoid.

And therefore we most earnestly entreat. First, That as you have voted your selves the supreme Authority, so you will exactly preserve the same entire in it self, without intermixing again with any other whatsoever.

Secondly, That you will precisely hold your selves to the supreme end, the Freedom of the People; as in other things, so in that necessary and essential part, of speaking, writing, printing, and publishing their minds freely; without seting of Masters, Tutors, and Controulers over them; and tor that end, to revoke all Ordinances and Orders to the contrary.

Thirdly, That you will fix us onely in a Civil Jurisdiction, refering the Military to Act distinct, and within it self, except in cases of warlike opposition to Civil Authority.

Fourthly, That you will recal that oppressive Ordinance for Tyths, upon treble damages; that so, as we have rejoyced in the notion, we may not have cause to grieve, but to rejoyce also in the exercise of your supreme Authority; and that the whole Nation in this blessed opportunity may receive a full reward of true Freedom for its large expense of bloud and treasure, and by your Wisdom and Fidelity, be made happy to all Future Generations.

Die Jovis, January 18. 1648.

The House being informed that divers Inhabitants within the Citie of London and Borough of Southwark, were at the Dore; they were called in, and then presented a Petition to this House; which after the Petitioners were withdrawn, was read, and was entituled, The humble Petition of firm and constant friends to Parliament and Common-wealth, the Presenters and Promoters of the late large Petition of Sept. 11. 1648.

Ordered by the Commons assembled in Parliament, that the said Petition be referred to the Committee appointed yesterday to consider of Petitions of this nature.

Hen. Scobell cler. Parl. Dom. Com,

The Petitioners being again called in, M. Speaker by command of this House gave them this answer. Gentlemen, The House have read your Petition, and have referred it to a Committee to consider of the matters of consequence therein; and have taken notice of your continued good affections to this House, and they have commanded me to give you thanks for your good affections, and I do accordingly give you thanks for your good affections.

Hen. Scobell Cleric. Parl. Dom. Com.

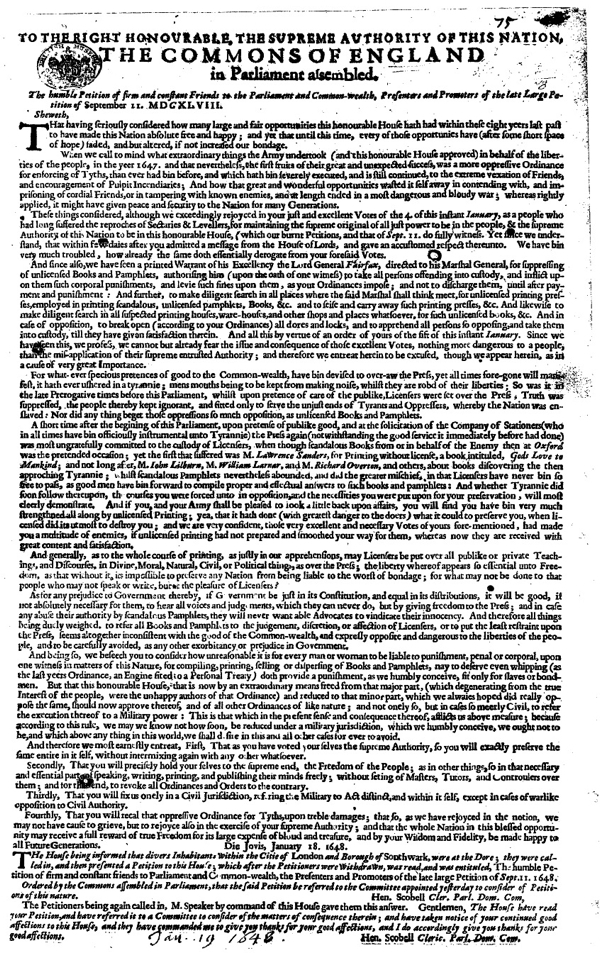

6.2. John Rushworth, A Petition concerning the Draught of an Agreement of the People (London: John Partridge, 20 January 1649).↩

Bibliographical Information

Full titleJohn Rushworth, A Petition from His Excellency Thomas Lord Fairfax And

the General Councel of Officers of the Army, To the Honourable, the Commons

of England in Parliament assembled, Concerning the Draught of An Agreement

of the People For a secure and present Peace, by them framed and prepared.

Together with the said Agreement presented on Saturuday, Jan. 20. And a Declaration

of his Excellency and the said General Councel, concerning the same. Tendered

to the Consideration of the people. By the Appointment of the Generall Councel

of Officers of the Army. Signed John Rushworth, Sec.

London, Printed for John Partridge, R. Harford, G. Calvert, and G. Whittington.

1649.

[Also known as "The Officers’ Agreement".]

Estimated date of publication20 January 1649.

Thomason Tracts Catalog informationTT1, p. 716; Thomason E. 539. (2.)

Editor’s Introduction

(Placeholder: Text will be added later.)

Text of Pamphlet

To the honorable the Commons of England in Parliament assembled;

The humble Petition of his Excellency Thomas Lord Fairfax, and the General Councel of Officers of the Army under his Command, concerning the Draught of An Agreement of the People, by them framed and prepared.

IN our late Remonstrance of the 18 of November last, we propounded (next after the matters of publike Justice) some Foundations for a general settlement of Peace in the Nation, which we therein desired might be formed and Established in the nature of a generall Contract or Agreement of the People; and since then, the matters so propounded be wholly rejected, or no consideration of them admitted in Parliament (though visibly of highest Moment to the Publique) and all ordinary Remedies being denyed, we were necessitated to an extraordinary way of Remedy; whereby to avoyd the mischiefs then at hand, and set you in a condition (without such obstructions or diversions by corrupt Members) to proceed to matters of publique Justice and general Settlement. Now as nothing did in our own hearts more justifie our late undertakings towards many Members in this Parliament, then the necessity thereof in order to a sound Settlement in the Kingdom, and the integrity of our intentions to make use of it only to that end: so we hold our selves obliged to give the People all assurance possible, That our opposing the corrupt closure endeavoured with the King, was not in designe to hinder Peace or Settlement, (thereby to render our employments, as Souldiers, necessary to be continued,) and that neither that extraordinary course we have taken, nor any other proceedings of ours, have been intended for the setting up of any particular Party or Interest, by or with which to uphold ourselves in Power and Dominion over the Nation, but that it was and is the desire of our hearts, in all we have done, (with the hindering of that imminent evil, and destructive conjunction with the King) to make way for the settlement of a Peace and Government of the Kingdom upon Grounds of common Freedom and Safety: And therefore because our former Overtures for that purpose (being only in general terms, and not reduced to a certainty of particulars fit for practise) might possibly be understood but as plausible pretences, not intended really to be put into effect, We have thought it our duty to draw out these generals into an intire frame of particulars, ascertained with such circumstances as may make it effectively practicable. And for that end, while your time hath been taken up in other matters of high and present Importance, we have spent much of ours in preparing and perfecting such a draught of Agreement, and in all things so circumstantiated, as to render it ripe for your speedier consideration, and the Kingdoms acceptance and practise (if approved,) and so we do herewith humbly present it to you. Now to prevent misunderstanding of our intentions therein, We have but this to say, That we are far from such a Spirit, as positively to impose our private apprehensions upon the judgments of any in the Kingdom, that have not forfeited their Freedom, and much lesse upon your selves: Neither are we apt in any wise to insist upon circumstantial things, or ought that is not evidently fundamental to that publique Interest for which You and We have declared and engaged; But in this Tender of it we humbly desire,

- 1. That whether it shall be fully approved by You and received by the People (as it now stands) or not, it may yet remain upon Record, before you, a perpetual witness of our real intentions and utmost endeavors for a sound and equal Settlement; and as a testimony whereby all men may be assured, what we are willing and ready to acquiesce in; and their jealousies satisfied or mouths stopt, who are apt to think or say, We have no bottom.

- 2. That (with all expedition which the immediate and pressing great affairs will admit) it may receive your most mature Consideration and Resolutions upon it, not that we desire either the whole, or what you shall like in it, should be by your Authority imposed as a Law upon the Kingdom, (for so it would lose the intended nature of An Agreement of the People,) but that (so far as it concurs with your own judgments) it may receive Your Seal of Approbation only.

- 3. That (according to the method propounded therein) it may be tendred to the People in all parts, to be subscribed by those that are willing, (as Petitions, and other things of a voluntary nature, are;) and that meanwhile, the ascertaining of those circumstances, which it refers to Commissioners in the several Counties, may be proceeded upon in a way preparatory to the practise of it: And if upon the Account of subscriptions (to be returned by those Commissioners in April next) there appear to be a general or common Reception of it amongst the People, or by the well-affected of them, and such as are not obnoxious for Delinquency; it may then take place, and effect according to the Tenor and Substance of it.

And Your Petitioners shall pray, &c.

By the Appointment of his Excellency, and the general Councel of Officers

of the Army.

Whitehall

Jan. 15. 1649.

Jo: Rushvvorth Secr’.

AN AGREEMENT OF THE PEOPLE OF ENGLAND, And the places therewith INCORPORATED, For a secure and present Peace, upon Grounds of Common Right, Freedom and Safety.

HAving by our late labors and hazards made it appear to the world at how high a rate we value our Just Freedom, And God having so far owned our cause as to deliver the Enemies thereof into our hands, We do now hold our selves bound in mutuall duty to each other to take the best care we can for the future, to avoyd both the danger of returning into a slavish condition, and the chargeable remedy of another War: For as it cannot be imagined, That so many of our Country men would have opposed us in this Quarrell, if they had understood their own good, so may we hopefully promise to our selves, That when our Common Right and Liberties shall be cleared, their endeavors will be disappointed, that seek to make themselves our Masters, since therefore our former oppressions, and not yet ended troubles, have been occasioned, either by want of frequent National Meetings in Councel, or by the undue or unequal Constitution thereof, or by rendering those meetings uneffectual. We are fully agreed and resolved (God willing) to provide, That hereafter our Representatives be neither left to an uncertainty for time, nor be unequally constituted, nor made useless to the ends for which they are intended.

1. That to prevent the many inconveniencies, apparently arising from the long continuance of the same persons in supream Authority, this Present Parliament end and dissolve upon, or before the last day of April, in the year of our Lord. 1649.

2. That the People of England (being at this day very unequally distributed, by Counties, Cities and Burroughs, for the Election of their Representatives) be indifferently proportioned: And to this end, That the Representative of the whole Nation shall consist of four hundred persons, or not above; and in each County, and the places thereto subjoyned, there shall be chosen, to make up the said Representative at all times, the several numbers here mentioned; VIZ.

| In the County of Kent, with the Burrough, Towns, and Parishes therein (except such as are hereunder particularly named) | ten. } | 10 |

| The City of Canterbury, with the Suburbs adjoyning, and Liberties thereof, | two. } | 2 |

| The City of Rochester, with the Parishes of Chatham and Strowd, | one. ] | 1 |

| The Cinque Ports in Kent and Sussex, viz. Dover, Rumney, Hyde, Sandwich, Hastings, with the townes of Rye and Winchelsey, | three. } | 3 |

| The County of Sussex, with the Burroughs, Towns and Parishes (therein except Chichester and the Cinque Ports) | eight. } | 8 |

| The City of Chichester, with the Suburbs and Liberties thereof, | one. ] | 1 |

| The County of Southampton, with the Burroughs, Towns and Parishes therein, except such as are hereunder named, | eight. } | 8 |

| The City of Winchester, with the Suburbs and Liberties thereof, | one. ] | 1 |

| The County of the town of Southampton, | one. ] | 1 |

| The County of Dorset, with the Burroughs, Townes and Parishes therein (except Dorchester) | seven. } | 7 |

| The Town of Dorchester, | one. ] | 1 |

| The County of Devon, with the Burroughs, Towns and Parishes therein, except such as are hereunder particularly named, | twelve.} | 12 |

| The City of Excester, | two. ] | 2 |

| The Town of Plymouth, | two. ] | 2 |

| The Town of Barnstaple, | one. ] | 1 |

| The County of Cornwall, with the Burroughs, Towns, and Parishes therein, | eight. } | 8 |

| The County of Somerset with the Burroughs, Townes and Parishes therein, except such as are hereunder named, | eight. } | 8 |

| The City of Bristoll, | three. ] | 3 |

| The Towne of Taunton-Deane, | one. ] | 1 |

| The County of Wilts, with the Burroughs, Towns and Parishes therein (except Salisbury), | seven. } | 7 |

| The City of Salisbury, | one. ] | 1 |

| The County of Berks, with the Burroughs, Towns and Parishes therein, except Reading, | five. } | 5 |

| The Town of Reading, | one. ] | 1 |

| The County of Surrey, with the Burroughs, Towns, and Parishes therein, except Southwarke, | five. } | 5 |

| The Burrough of Southwarke, | two. ] | 2 |

| The County of Middlesex, with the Burroughs, Towns, and Parishes therein, except such as are hereunder named, | four. } | 4 |

| The City of London, | eight. ] | 8 |

| The City of VVestminster, and the Dutchy, | two. ] | 2 |

| The County of Hartford, with the Burroughs, Towns, and Parishes therein, | six. } | 6 |

| The County of Buckingham with the Burroughs, Towns and Parishes therein, | six. } | 6 |

| The County of Oxon, with the Burroughs, Towns, and Parishes therein (except such as are here under-named) | four. } | 4 |

| The City of Oxon, | two. ] | 2 |

| The University of Oxon, | two. ] | 2 |

| The County of Glocester, with the Burroughs, towns and Parishes therein (except Glocester) | seven. } | 7 |

| The City of Glocester, | two. ] | 2 |

| The County of Hereford, with the Burroughs, towns, and Parishes therin (except Hereford) | four. } | 4 |

| The Citie of Hereford, | one. ] | 1 |

| The County of Worcester, with the Burroughs, towns, and Parishes therein (except Worcester) | foure. } | 4 |

| The City of Worcester, | two. ] | 2 |

| The County of Warwicke, with the Burroughs, townes, and Parishes therein (except Coventrey) | five. } | 5 |

| The City of Coventrey, | two. ] | 2 |

| The County of Northampton, with the Burroughs, towns and Parishes therein (except Northampton) | five. } | 5 |

| The Town of Northampton, | one. ] | 1 |

| The County of Bedford, with the Burroughs, townes, and Parishes therein, | foure. } | 4 |

| The County of Cambridge, with the Burroughs, towns, and Parishes therein (except such as are here under particularly named) | foure. } | 4 |

| The University of Cambridge, | two. ] | 2 |

| The Town of Cambridge, | two. ] | 2 |

| The County of Essex, with the Burroughs, towns, and Parishes therein (except Colchester) | eleven.} | 11 |

| The Town of Colchester, | two. ] | 2 |

| The County of Suffolk, with the Burroughs, Towns, and Parishes therein (except such as are hereunder named) | ten. } | 10 |

| The Town of Ipswich, | two. ] | 2 |

| The Town of S. Edmonds Bury, | one. ] | 1 |

| The County of Norfolk, with the Burroughs, Towns, and Parishes therein (except such as are hereunder named) | nine. } | 9 |

| The City of Norwich, | three. ] | 3 |

| The Town of Lynne, | one. ] | 1 |

| The Town of Yarmouth, | one. ] | 1 |

| The County of Lincoln, with the Burroughs, Towns, and Parishes therein (except the City of Lincoln, and the town of Boston) | eleven.} | 11 |

| The City of Lincoln, | one. ] | 1 |

| The Town of Boston, | one. ] | 1 |

| The County of Rutland, with the Burroughs, Townes, and Parishes therein, | one. } | 1 |

| The County of Huntington, with the Burroughs, Towns and Parishes therein, | three. } | 3 |

| The County of Leicester, with the Burroughs, Townes and Parishes therein (except Leicester) | five. } | 5 |

| The Town of Leicester, | one. ] | 1 |

| The County of Nottingham, with the Burroughs, Towns and Parishes therein (except Nottingham) | foure. } | 4 |

| The Town of Nottingham, | one. ] | 1 |

| The County of Derby, with the Burroughs, Townes, and Parishes therein (except Derby) | five. } | 5 |

| The Town of Derby, | one. ] | 1 |

| The County of Stafford, with the City of Lichfield, the Burroughs, towne and Parishes therein, | six. } | 6 |

| The County of Salop, with the Burroughs, towns, and Parishes therein (except Shrewsbury) | six. } | 6 |

| The Town of Shrewsbury, | one. ] | 1 |

| The County of Chester, with the Burroughs, townes, and Parishes therein (except Chester) | five. } | 5 |

| The City of Chester, | two. ] | 2 |

| The County of Lancaster, with the Burroughs, townes, and Parishes therein (except Manchester) | six. } | 6 |

| The town of Manchester, and the Parish, | one. ] | 1 |

| The County of Yorke, with the Burroughs, towns, and Parishes, therein, except such as are here under named, | fifteen. } | 15 |

| The City and County of the City of Yorke, | three. ] | 3 |

| The Town and County of Kingston upon Hull, | one. ] | 1 |

| The town and Parish of Leeds, | one. ] | 1 |

| The County Palatine of Duresme, with the Burroughs, towns, and Parishes therein, except Duresme and Gateside, | three. } | 3 |

| The City of Duresme, | one. ] | 1 |

| The County of Northumberland, with the Burroughs, towns and Parishes therein, except such as are here under named, | three. } | 3 |

| The Town and County of Newcastle upon Tyne, with Gateside, | two. ] | 2 |

| The Town of Berwicke, | one. ] | 1 |

| The County of Cumberland, with the Burroughs, towns, and Parishes therein, | three. } | 3 |

| The County of Westmerland, with the Burroughs, towns and Parishes therein, | two. } | 2 |

| The Isle of Anglesey (with the Parishes therein) | two. ] | 2 |

| The County of Brecknock, with the Burroughs, towns, and Parishes therein, | three. } | 3 |

| The County of Cardigan, with the Burroughs and Parishes therein, | three. } | 3 |

| The County of Caermarthen, with the Burroughs and Parishes therein, | three. } | 3 |

| The County of Carnarvon, with the Burroughs and Parishes therein, | two. ] | 2 |

| The County of Denbigh, with the Burroughs and Parishes therein | two. ] | 2 |

| The County of Flint, with the Burroughs and Parishes therein, | one. ] | 1 |

| The County of Monmouth, with the Burroughs and Parishes therein, | foure. } | 4 |

| The County of Glamorgan, with the Burroughs and Parishes therein, | foure. } | 4 |

| The County of Merioneth, with the Burroughs and Parishes therein, | two. } | 2 |

| The County of Mountgomery, with the Burroughs and Parishes therein, | three. } | 3 |

| The County of Radnor, with the Burroughs and Parishes therein, | two. ] | 2 |

| The County of Pembroke, with the Burroughs, Towns and Parishes therein, | foure. } | 4 |

Provided, That the first or second Representative may (if they see cause) assigne the remainder of the foure hundred Representors, (not hereby assigned) or so many of them as they shall see cause for, unto such Counties as shall appear in this present distribution to have lesse then their due proportion. Provided also, That where any Citie or Burrough to which one Representor or more is assign’d shall be found in a due proportion, not competent alone to elect a Representor, or the number of Representors assign’d thereto, it is left to future Representatives to assigne such a number of Parishes or Villages neare adjoyning to such City, or Burrough, to be joyned therewith in the Elections, as may make the same proportionable.

3. That the people do of course choose themselves a Representative once in two yeares, and shall meet for that purpose upon the first Thursday in every second May by eleven of Clock in the morning, and the Representatives so chosen to meet upon the second Thursday in June following at the usuall place in Westminster, or such other place as by the foregoing Representative, or the Councell of State in the intervall, shall be from time to time appointed and published to the People, at the least twenty daies before the time of Election. And to continue their Session there or elsewhere untill the second Thursday in December following, unlesse they shall adjourne, or dissolve themselves sooner, but not to continue longer. The Election of the first Representative to be on the first Thursday in May, 1649. And that, and all future Elections to be according to the rules prescribed for the same purpose in this Agreement, viz.

- 1. That the Electors in every Division, shall be Natives, or Denizons of England, not persons receiving Almes, but such as are assessed ordinarily, towards the reliefe of the poore; not servants to, and receiving wages from any particular person. And in all Elections, (except for the Universities,) they shall be men of one and twenty yeares old, or upwards, and housekeepers, dwelling within the Devision for which the Election is provided, That untill the end of seven yeares next ensuing the time herein limited for the end of this present Parliament, no person shall be admitted to, or have any hand or voice in such Elections, who hath adhered unto, or assisted the King against the Parliament, in any the late Warres, or Insurrections, or who shall make, or joyne in, or abet any forcible opposition against this Agreement.

- 2. That such persons and such only, may be elected to be of the Representative, who by the rule aforesaid are to have voice in Elections in one place or other; provided, That of those, none shall be eligible for the first or second Representatives, who have not voluntarily assisted the Parliament against the King, either in person before the 14th. of June 1645. or else in Money, Plate, Horse, or Armes, lent upon the Propositions before the end of May 1643. or who have joyned in, or abetted the treasonable Engagement in London, in the year 1647. or who declared or engaged themselves for a Cessation of Armes with the Scots, that invaded this Nation, the last Summer, or for complyance with the Actors in any the insurrections, of the same Summer, or with the Prince of Wales, or his accomplices in the Revolted Fleete. And also provided, That such persons as by the rules in the preceding Article are not capable of electing untill the end of seven years, shall not be capable to be elected untill the end of foureteen years, next ensuing. And we do desire and recommend it to all men, that in all times the persons to be chosen for this great trust, may be men of courage, fearing God, and hating covetousnesse, and that our Representatives would make the best Provisions for that end.

- 3. That who ever, by the two rules in the next preceding Articles, are incapable of Election, or to be elected, shall assume to vote in, or be present at such Elections for the first or second Representative, or being elected shall presume to sit or vote in either of the said Representatives, shall incur the pain of confiscation of the moyety of his Estate, to the use of the publike, in case he have any Estate visible, to the value of fifty pounds. And if he have not such an Estate, then shall incur the pain of imprisonment, for three months; And if any person shall forcibly oppose, molest, or hinder the people, (capable of electing as aforesaid) in their quiet and free Election of Representors, for the first Representative, then each person so offending shall incur the penalty of confiscation of his whole Estate, both reall and personall; and (if he have not an Estate to the value of fifty pounds,) shall suffer imprisonment during one whole year without Bayle, or mainprize. Provided, That the Offender in each such case, be convicted within three Months next after the committing of his offence, And the first Representative is to make further provision for the avoyding of these evills in after Elections.

- 4. That to the end, all Officers of State may be certainly accomptable, and no factions made to maintain corrupt interests, no Member of a Councel of State, nor any Officer of any salary forces in Army, or Garison, nor any Treasurer or Receiver of publique monies, shall (while such) be elected to be of a Representative. And in case any such Election shall be, the same to be void. And in case any Lawyer shall be chosen of any Representative, or Councel of State, then he shall be uncapable of practice as a Lawyer, during that trust.

- 5. For the more convenient Election of Representatives, each County wherein more then three Representors are to be chosen, with the Townes Corporate and Cities, (if there be any) lying within the compasse thereof, to which no Representors are herein assigned, shall be divided by a due proportion into so many, and such parts, as each part may elect two, and no part above three Representors; For the setting forth of which Divisions, and the ascertaining of other circumstances hereafter exprest, so as to make the Elections lesse subject to confusion, or mistake, in order to the next Representative, Thomas Lord Grey of Grooby, Sir John Danvers, Sir Henry Holcraft, Knights; Moses Wall Gentleman, Samuel Moyer, John Langley, William Hawkins, Abraham Babington, Daniel Taylor, Mark Hilsley, Richard Price, and Col. John White, Citizens of London, or any five, or more of them are intrusted to nominate and appoint under their Hands and Seales, three or more fit persons in each County, and in each Citie, and Borough, to which one Representor or more is assigned to be as Commissioners for the ends aforesaid, in the respective Counties, Cities, and Burroughs, and by like writing under their Hands and Seales shall certifie into the Parliament Records, before the fourteenth day of February next, the names of the Commissioners so appointed for the respective Counties, Cities, and Burroughs, which Comissioners or any three, or more of them, for the respective Counties, Cities, and Burroughs, shall before the end of February next, by writing under their Hands and Seales, appoint two fit and faithfull persons, or more in each Hundred, Lath, or Wapentake, within the respective Counties, and in each Ward, within the City of London, to take care for the orderly taking of all voluntary subscriptions to this Agreement by fit persons to be imploy’d for that purpose in every Perish who are to returne the subscriptions so taken to the persons that imployed them, (keeping a transcript thereof to themselves,) and those persons keeping like Transcripts to return the Originall subscriptions to the respective Commissioners, by whom they were appointed, at, or before the fourteenth of Aprill next, to be registred and kept in the County Records, for the said Counties respectively, and the subscriptions in the City of London, to be kept in the chief Court of Record for the said City. And the Commissioners for the other Cities and Borroughs respectively, are to appoint two or more fit persons in every Parish within their Precincts to take such subscriptions, and (keeping transcripts thereof) to return the Originalls to the respective Commissioners by the said fourteenth of Aprill next, to be registred and kept in the chief Court within the respective Cities and Burroughs. And the same Commissioners, or any three, or more of them, for the severall Counties, Cities, and Boroughs, respectively, shall, where more then three Representors are to be chosen, divide such Counties (as also the City of London) into so many, and such parts as are aforementioned, and shall set forth the bounds of such divisions, and shall in every County, City, and Borough (where any Representors are to be chosen) and in every such division as aforesaid within the City of London, and within the severall Counties so divided, respectively, appoint one certaine place wherein the people shall meet for the choise of their Representors, and some one fit Person or more inhabiting within each Borough, City, County, or Division, respectively, to be present at the time and place of Election, in the nature of Sheriffes to regulate the Elections, and by Pole, or otherwise, clearly to distinguish and judge thereof, and to make returne of the Person or Persons Elected as is hereafter exprest, and shall likewise in writing under their hands and Seales, make Certificates of the severall Divisions (with the bounds thereof) by them set forth, and of the certaine places of meeting, and Persons, in the nature of Sheriffes appointed in them respectively as aforesaid,1 and cause such Certificates to be returned into the Parliament Records before the end of April next, and before that time shall also cause the same to be published in every Parish within the Counties, Cities, and Boroughs respectively, and shall in every such Parish likewise nominate and appoint (by Warrant under their hands and Seals) one Trusty person, or more, inhabiting therein, to make a true list of al the Persons within their respective Parishes, who according to the rules aforegoing are to have voyce in the Elections, and expressing, who amongst them are by the same rules capable of being Elected, and such List (with the said Warrant) to bring in, and returne at the time and place of Election, unto the Person appointed in the nature of Sheriffe, as aforesaid, for that Borough, City, County, or Division respectively; which Person so appointed as Sheriffe being present at the time and place of Election; or in case of his absence by the space of one houre after the time limited for the peoples meeting, then any Person present that is eligible, as aforesaid, whom the people then and there assembled shall chuse for that end, shall receive and keep the said Lists, and admit the Persons therein contained, or so many of them as are present unto a free Vote in the said Election, and having first caused this Agreement to be publiquely read in the audience of the people, shall proceed unto, and regulate and keep peace and order in the Elections, and by Pole, or otherwise, openly distinguish and judge of the same: And thereof by Certificate, or writing under the hands and Seales of himself, and six or more of the Electors (nominating the Person or Persons duly Elected) shall make a true returne into the Parliament Records, within one and twenty dayes after the Election (under paine for default thereof, or for making any false Returne to forfeit one hundred pounds to the Publique use.) And shall also cause Indentures to be made, and interchangeably sealed and delivered betwixt himselfe, and six or more of the said Electors on the one part, and the Persons, or each Person Elected severally on the other part, expressing their Election of him as a Representor of them, according to this Agreement, and his acceptance of that trust, and his promise accordingly to performe the same with faithfulnesse, to the best of his understanding and ability, for the glory of God, and good of the people.

This course is to hold for the first Representative, which is to provide for the ascertaining of these Circumstances in order to future Representatives.

4. That one hundred and fifty Members at least be alwaies present in each sitting of the Representative, at the passing of any Law, or doing of any Act, whereby the people are to be bound; saving, That the number of sixty may make an House for Debates, or Resolutions that are preparatory thereunto.

5. That each Representative shall within twenty dayes after their first meeting appoint a Councell of State for the managing of Publique Affaires, untill the tenth day after the meeting of the next Representative, unlesse that next Representative thinke fit to put an end to that trust sooner. And the same Councell to Act, and proceed therein, according to such Instructions and limitations as the Representative shall give, and not otherwise.

6. That in each intervall betwixt Bienniall Representatives, the Councell of State (in case of imminent danger, or extreame necessity) may summon a Representative to be forthwith chosen, and to meet; so as the Session thereof continue not above foure-score dayes, and so as it dissolve, at least, fifty dayes before the appointed time for the next Bienniall Representative, and upon the fiftyeth day so preceeding it shall dissolve of course, if not otherwise dissolved sooner.

7. That no Member of any Representative be made either Receiver, Treasurer, or other Officer, during that imployment, saving to be a Member of the Councell of State.

8. That the Representatives have, and shall be understood, to have, the Supreame trust in order to the preservation and Government of the whole, and that their power extend, without the consent or concurrence of any other Person or Persons, to the erecting and abolishing of Courts of Justice, and publique Offices, and to the enacting, altering, repealing, and declaring of Lawes, and the highest and finall Judgement, concerning all Naturall or Civill things, but not concerning things Spirituall or Evangelicall; Provided, that even in things Naturall and Civill these six particulars next following are, and shall be understood to be excepted, and reserved from our Representatives, viz.

- 1. We doe not impower them to imprest or constraine any Person to serve in Forraigne Warre either by Sea or Land, nor for any Millitary Service within the Kingdome, save that they may take order for the the forming, training and exercising of the people in a Military way to be in readinesse for resisting of Forrain Invasions, suppressing of suddain Insurrections, or for assisting in execution of Law; and may take order for the imploying and conducting of them for those ends; provided, That even in such cases none be compellable to goe out of the County he lives in, if he procure another to serve in his roome.

- 2. That after the time herein limited for the commencement of the first Representative, none of the people may be at any time questioned for any thing said or done in relation to the late Warres, or publique differences, otherwise then in execution or pursuance of the determinations of the present House of Commons against such as have adhered to the King, or his interest against the people: And saving that Accomptants for publique monies received, shall remaine accomptable for the same.

- 3. That no securities given, or to be given by the Publique Faith of the Nation, nor any engagements of the Publique Faith for satisfaction of debts and dammages, shal be made void or invalid by the next, or any future Representatives; except to such Creditors, as have, or shall have justly forfeited the same; and saving, That the next Representative may confirme or make null, in part, or in whole, all gifts of Lands, Monies, Offices, or otherwise, made by the present Parliament to any Member or Attendant of either House.

- 4. That in any Lawes hereafter to be made, no person, by vertue of any tenure, grant, Charter, patent, degree or birth, shall be priviledged from subjection thereto, or from being bound thereby, as well as others.

- 5. That the Representative may not give judgement upon any mans person or estate, where no Law hath before provided; save onely in calling to Account, and punishing publique Officers for abusing or failing their trust.

- 6. That no Representative may in any wise render up, or give, or take away any the Foundations of common Right, Liberty and Safety contained in this Agreement; nor levell mens Estates, destroy Propriety, or make all things common: And that in all matters of such fundamentall concernment, there shall be a liberty to particular Members of the said Representatives to enter their dissents from the major vote.

9. Concerning Religion, we agree as followeth:

- 1. It is intended, That Christian Religion be held forth and recommended, as the publike Profession in this Nation (which wee desire may by the grace of God be reformed to the greatest purity in Doctrine, Worship and Discipline, according to the Word of God.) The instructing of the People whereunto in a publike way (so it be not compulsive) as also the maintaining of able Teachers for that end, and for the confutation or discovery of Heresie, Errour, and whatsoever is contrary to sound Doctrine, is alowed to be provided for by our Representatives; the maintenance of which Teachers may be out of a publike Treasury, and wee desire not by tithes. Provided, That Popery or Prelacy be not held forth as the publike way or profession in this Nation.

- 2. That to the publique Profession so held forth none be compelled by penalties or otherwise, but onely may be endeavoured to be wonne by sound Doctrine, and the Example of a good Conversation.

- 3. That such as professe Faith in God by Jesus Christ (however differing in judgement from the Doctrine, Worship or Discipline publikely held forth, as aforesaid) shall not be restrained from, but shall be protected in the profession of their Faith and exercise of Religion according to their Consciences in any place (except such as shall be set apart for the publick Worship, where wee provide not for them, unlesse they have leave) so as they abuse not this liberty to the civil injury of others, or to actuall disturbance of the publique peace on their parts; neverthelesse it is not intended to bee hereby provided, That this liberty shall necessarily extend to Popery or Prelacy.

- 4. That all Lawes, Ordinances, Statutes, and clauses in any Law, Statute, or Ordinance to the contrary of the liberty provided for in the two particulars next preceding concerning Religion be and are hereby repealed and made void.

10. It is agreed, That whosoever shall by Force of Armes, resist the Orders of the next or any future Representative (except in case where such Representative shall evidently render up, or give, or take away the Foundations of common Right, Liberty and Safety contain’d in this Agreement) shall forthwith after his or their such Resistance lose the benefit and protection of the Laws, and shall be punishable with Death, as an Enemy and Traitour to the Nation.

The form of subscription for the Officers of the Army.

Of the things exprest in this Agreement, The certain ending of this Parliament (as in the first Article) The equall or proportionable distribution of the number of the Representators to be elected (as in the second.) The certainty of the peoples meeting to elect for Representatives Bienniall, and their freedome in Elections with the certainty of meeting, sitting and ending of Representatives so elected (which are provided for in the third Article) as also the Qualifications of Persons to elect or be elected (as in the first and second particulars under the third Article) Also the certainty of a number for passing a Law or preparatory debates (provided for in the fourth Article) The matter of the fifth Article, concerning the Councel of State, and the sixth concerning the calling, sitting and ending of Representatives extraordinary; Also the power of Representatives, to be, as in the eighth Article, and limitted, as in the six reserves next foling the same; Likewise the second and third particulars under the ninth Article concerning Religion, and the whole matter of the tenth Article; (All these) we doe account and declare to be Fundamentall to our common Right, Liberty, and Safety; And therefore doe both agree thereunto, and resolve to maintain the same, as God shall enable us. The rest of the matters in this Agreement, wee account to be usefull and good for the Publike, and the particular circumstances of Numbers, Times and Places expressed in the severall Articles, we account not Fundamentall, but we finde them necessary to be here determined for the making the Agreement certain and practicable, and do hold those most convenient that are here set down, and therefore do positively agree thereunto.

Concerning the Agreement by them framed in order to peace, and from them tendred to the People of England.

HAVING ever since the end of the first War longingly waited for some such settlement of the Peace and Government of this Nation, whereby the Common Rights, Liberties and safety thereof, might in future be more hopefully provided for, and therein something gained, which might be accounted to the present age and posterity (through the mercy of God) as a fruit of their labours, hazards and sufferings, that have engaged in the common cause, as some price of the bloud spilt, and ballance to the publique expence and damage sustained in the War, and as some due improvement of that successe, and blessing God hath pleased to give therein: And having not found any such Establishment assayed or endeavoured by those whose proper worke it was, but the many addresses and desires of ourselves, and others, in that behalfe, rejected, discountenanced and opposed, and onely a corrupt closure endeavoured with the King, on tearmes, serving onely to his interest, and theirs that promoted the same; And being thereupon (for the avoidance of the evil thereof, and to make way for some better settlement) necessitated to take extraordinary wayes of remedy (when the ordinary were denied;) Now to exhibit our utmost endeavors for such a settlement, whereupon we, and other Forces, (with which the Kingdome hath so long beene burthened above measure, and whose continuance shall not be necessary for the immediate safety and quiet thereof) may with comfort to our selves, and honesty towards the publique, disband, and returne to our homes and callings; and to the end mens jealousies and fears may be removed concerning any intentions in us to hold up our selves in power, to oppresse or domineer over the people by the sword; And that all men may fully understand those grounds of Peace and Government wherupon (they may rest assured) We shall for our parts acquiesce; We have spent much time to prepare, and have at last (through the blessing of God) finished a Draught of such a settlement, in the nature of an Agreement of the People for Peace amongst themselves; Which we have lately presented to the Honourable the Commons now assembled in Parliament, and doe herewith tender to the people of this Nation.

We shal not otherwise commend it, then to say, It contains the best and most hopefull Foundations for the Peace, & future wel Government of this Nation, that we can devise or think on, within the line of humane power, and such, wherin all the people interested in this Land (that have not particular interests of advantage & power over others, divided from that which is common and publique) are indifferently and equally provided for, save where any have justly forfeited their share in that common interest by opposing it, and so rendred themselves incapable thereof (at least) for some time: And we call the Consciences of all that reade or hear it, to witnesse, whether wee have therein provided or propounded any thing of advantage to our selves in any capacity above others, or ought, but what is as good for one as for another: And therefore as we doubt not but that (the Parliament being now freed from the obstructing and perverting Councels of such Members, by many of whom a corrupt compliance with the Kings Interest hath beene driven on, and all settlement otherwise hath hitherto beene hindred) Those remaining worthy Patriots to whom we have presented the Agreement, will for the maine allow thereof, and give their seale of Approbation thereby; So we desire and hope, That all good People of England whose heart God shall make sensible of their, and our common concernment therein, and of the usefulnesse and sutablenesse thereof to the publique ends it holds forth, will cordially embrace it, and by subscription declare their concurrence, and accord thereto, when it shall be tendred to them, as is directed therein; wherein, if it please God wee shall finde a good Reception of it with the people of the Nation, or the Well-affected therein, We shall rejoyce at the hoped good to the Common-wealth, which (through Gods mercy) may redound therefrom, and that God hath vouchsafed thereby to make us instrumentall for any good settlement to this poor distracted Country, as he hath formerly made us for the avoiding of evill. But if God shall (in his Righteous Judgement towards this Land) suffer the people to be so blinded as not to see their own common good and freedome, endeavoured to be provided for therein, or any to be so deluded (to their own and the publique prejudice) as to make opposition thereto, whereby the effect of it be hindred, we have, yet, by the preparation and tender of it discharged our Consciences to God, and duty to our native Country in our utmost endeavours for a settlement, (to the best of our understandings) unto a just publique interest; And hope we shall be acquitted before God and good men, from the blame of any further troubles, distractions, or miseries to the Kingdom, which may arise through the neglect or rejection thereof, or opposition thereto.

Now whereas there are many good things in particular ters which our own Reasons & observations or the Petitions of others have suggested, and which we hold requisite to be provided for in their proper time and way (as the setting of moderate Fines upon such of the Kings party, as shal not be excepted for life, with a certain day for their coming in and submitting, and an Act of pardon to such as shall come in and submit accordingly, or have already compounded, The setling of a Revenue for all necessary publique uses, in such a way as the people may be most eased, The assigning and ascertayning of securities for Souldiers Arrears; and for publique Debts and Damages. The taking away of Tithes, and putting that maintenance which shall be thought competent for able Teachers to instruct the people, into some other way, lesse subject to scruple or contention, the clearing and perfecting of Accompts for all publique Monies, the relieving of prisoners for Debt; the removing or reforming of other evills or inconveniencies in the present Lawes, and Administrations thereof, the redresse of abuses, and supplying of Defects therein, the putting of all the Lawes and proceedings thereof into the English tongue, the reducing of the course of Law to more brevity and lesse charge, the setling of Courts of Justice and Record in each County or lesse Divisions of the Kingdome, and the erecting of Courts of Merchants for controversies in trading, and the like.) These and many other things of like sort being of a particular nature, and requiring very particular and mature consideration, with larger experience in the particular matters then we have, and much Caution, that by taking away of present Evills greater inconveniences may not ensue for want of other provisions in the room thereof, where it is necessary; and we (for our parts) being far from any Desire or thought to assume or exercise a Law-giving, or Judiciall power over the Kingdome, or to meddle in any thing save the fundamentall setling of that power in the most equall and hopefull way for Common Right, Freedom, and Safety (as in this Agreement) and having not meanes nor time for, nor the necessitie of some present generall settlement admitting the delay of, such a consideration, as seems requisite in relation to such numerous particulars, we have purposely declined the inserting of such things into this Agreement. But (as we have formerly expressed our desires that way, so) when the matters of publique Justice, and generall settlement are over, we shall not be wanting (if needfull) humbly to recommend such particulars to the Parliament, by whom they may more properly, safely, and satisfactorily be provided for, and we doubt not but they will be so, such of them, at least, as are of more neare and present concernment, by this Parliament, and the rest by future Representatives in due time.

And thus we recommend for present the businesse of this Agreement without further addition to the best consideration of all indifferent and equall minded men, and commit the issue thereof (as of all our wayes and concernments) to the good pleasure of the Lord, whose will is better to us then our own, or any inventions of ours, who hath decreed and promised better things then we can wish or imagine, and who is most faithfull to accomplish them in the best way and season.

By the appointment of the Generall Councell of Officers.

Iohn Rushworth Secretary.

FINIS.

Endnotes

[1 ] Memorandum, That the Commissioners for the respective Counties, Cities, and Boroughs, are to returne a Computation of the number of Subscribers in the severall Parishes unto the Trustees herein named before the end of April next, at such place, and in such forme as the said Trustees, or any five or more of them shall direct.

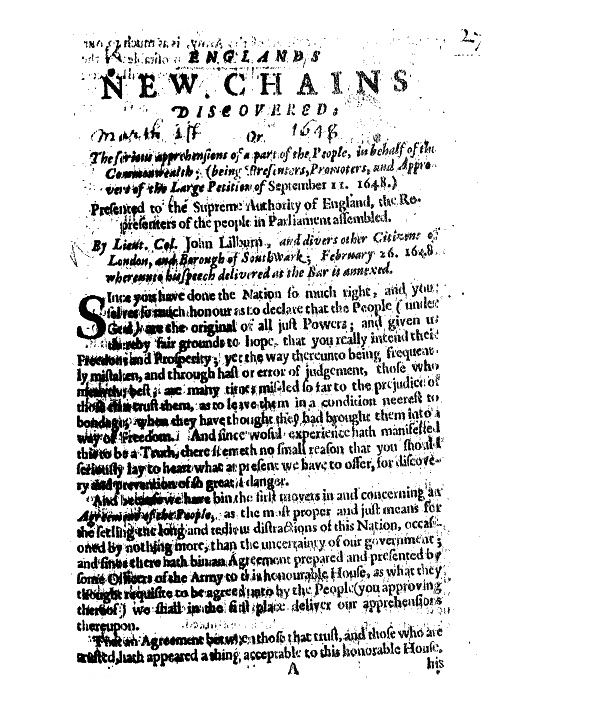

6.3. John Lilburne, Englands New Chains Discovered (n.p., 26 February 1649).↩

Bibliographical Information

Full titleJohn Lilburne, Englands New Chains Discovered; or The serious apprehensions of a part of the People, in behalf of the Commonwealth; (being Presenters, Promoters, and Approvers of the Large Petition of September 11. 1648.) Presented to the Supreme Authority of England, the Representers of the people in Parliament assembled. By Lieut. Col. John Lilburn, and divers other Citizens of London, and Borough of Southwark; February 26. 1648. whereunto his speech delivered at the bar is annexed.

Estimated date of publication26 February 1649.

Thomason Tracts Catalog informationTT1, p. 726; Thomason E. 545. (27.)

Editor’s Introduction

(Placeholder: Text will be added later.)

Text of Pamphlet

Since you have done the Nation so much right, and your selves so much honour as to declare that the People (under God) are the original of all just Powers; and given us thereby fair grounds to hope, that you really intend their Freedom and Prosperity; yet the way thereunto being frequently mistaken, and through hast or error of judgement, those who mean the best, are many times mis-led so far to the prejudice of those that trust them, as to leave them in a condition neerest to bondage, when they have thought they had brought them into a way of Freedom. And since woful experience hath manifested this to be a Truth, there seemeth no small reason that you should seriously lay to heart what at present we have to offer, for discovery and prevention of so great a danger. And because we have bin the first movers in and concerning an Agreement of the People, as the most proper and just means for the setting the long and tedious distractions of this Nation, occasioned by nothing more, than the uncertainty of our government; and since there hath bin an Agreement prepared and presented by some Officers of the Army to this honourable House, as what they thought requisite to be agreed unto by the People (you approving thereof) we shall in the first place deliver our apprehensions thereupon.

That an Agreement between those that trust, and those who are trusted hath appeared a thing acceptable to this honorable House, his Excellency, and the Officers of the Army, is as much to our rejoycing, as we conceive it just in it self, and profitable for the Common-wealth, and cannot doubt but that you will protect those of the people, who have no waies forfeited their Birth-right, in their proper liberty of taking this, or any other, as God and their own Considerations shall direct them.

Which we the rather mention, for that many particulars in the Agreement before you, are upon serious examination thereof, dissatisfactory to most of those who are very earnestly desirous of an Agreement, and many very material things seem to be wanting therein, which may be supplyed in another: As

1. They are now much troubled there should be any Intervalls between the ending of this Representative, and the begining of the next as being desirous that this present Parliament that hath lately done so great things in so short a time, tending to their Liberties, should sit; until with certainty and safety they can see them delivered into the hands of another Representative, rather than to leave them (though never so small a time) under the dominion of a Councel of State; a Constitution of a new and unexperienced Nature, and which they fear, as the case now stands, may design to perpetuate their power, and to keep off Parliaments for ever.

2. They now conceive no less danger, in that it is provided that Parliaments for the future are to continue but 6. moneths, and a Councel of State 18. In which time, if they should prove corrupt, having command of all Forces by Sea and Land, they will have great opportunities to make themselves absolute and unaccountable: And because this is a danger, than which there cannot well be a greater; they generally incline to Annual Parliaments, bounded and limited as reason shall devise, not dissolvable, but to be continued or adjourned as shall seem good in their discretion, during that yeer, but no longer 3 and then to dissolve of course, and give way to those who shall be chosen immediatly to succeed them, and in the Intervals of their adjournments, to entrust an ordinary Committee of their own members, as in other cases limited and bounded with express instructions, and accountable to the next Session, which will avoid all those dangers feared from a Councel of State, as at present this is constituted.

3. They are not satisfied with the clause, wherein it is said, that the power of the Representatives shall extend to the erecting and I abolishing of Courts of justice; since the alteration of the usual way of Tryals by twelve sworn men of the Neighborhood, may be included therein: a constitution so equal and just in it self, as that they conceive it ought to remain unalterable. Neither is it cleer what is meant by these words, (viz.) That the Representatives have the highest final judgement. They conceiving that their Authority in these cases, is onely to make Laws, Rules, and Directions for other Courts and Persons assigned by Law for the execution thereof; unto which every member of the Commonwealth, as well those of the Representative, as others, should be alike subject; it being likewise unreasonable in it self, and an occasion of much partiality, injustice, and vexation to the people, that the Lawmakers, should be Law-executors.

4. Although it doth provide that in the Laws hereafter to be made) no person by vertue of any Tenure, Grant, Charter, Patent, Degree, or Birth, shall be priviledged from subjection thereunto, or from being bound thereby, as well as others; Yet doth it not null and make void those present Protections by Law, or otherwise; nor leave all persons, as well Lords as others, alike liable in person and estate, as in reason and conscience they ought to be.

5. They are very much unsatisfied with what is exprest as a reserve from the Representative, in matters of Religion, as being very obscure, and full of perplexity, that ought to be most plain and clear; there having occurred no greater trouble to the Nation about any thing than by the intermedling of Parliaments in matters of Religion.

6. They seem to conceive it absolutely necessary, that there be in their Agreement, a reserve from ever having any Kingly Government, and a bar against restoring the House of Lords, both which are wanting in the Agreement which is before you.

7. They seem to be resolved to take away all known and burdensome grievances, as Tythes, that great oppression of the Countries industry and hindrance of Tillage: Excise, and Customs, Those secret thieves, and Robbers, Drainers of the poor and middle sort of People, and the greatest Obstructers of Trade, surmounting all the prejudices of Ship-mony, Pattents, and Projects, before this Parliament: also to take away all Monopolizing Companies of Marchants, the hinderers and decayers of Clothing and Cloth-working, Dying, and the like useful professions; by which thousands of poor people might be set at work, that are now ready to starve, were Marchandizing restored to its due and proper freedom: they conceive likewise that the three grievances before mentioned, (viz.) Monopolizing Companies, Excise, and Customes, do exceedingly prejudice Shiping, and Navigation, and Consequently discourage Sea-men, and Marriners, and which have had no smal influence upon the late unhappy revolts which have so much endangered the Nation, and so much advantaged your enemies. They also incline to direct a more equal and lesse burdensome way for levying monies for the future, those other fore-mentioned being so chargable in the receipt, as that the very stipends and allowance to the Officers attending thereupon would defray a very great part of the charge of the Army; whereas now they engender and support a corrupt interest. They also have in mind to take away all imprisonment of disabled men, for debt; and to provide some effectual course to enforce all that are able to a speedy payment, and not suffer them to be sheltered in Prisons, where they live in plenty, whilst their Creditors are undone. They have also in mind to provide work, and comfortable maintainance for all sorts of poor, aged, and impotent people, and to establish some more speedy, lesse troublesome and chargeable way for deciding of Controversies in Law, whole families having been ruined by seeking right in the wayes yet in being: All which, though of greatest and most immediate concernment to the People, are yet omitted in their Agreement before you.

These and the like are their intentions in what they purpose for an Agreement of the People, as being resolved (so far as they are able) to lay an impossibility upon all whom they shall hereafter trust, of ever wronging the Common wealth in any considerable measure, without certainty of ruining themselves, and as conceiving it to be an improper tedious, and unprofitable thing for the People, to be ever runing after their Representatives with Petitions for redresse of such Grievances as may at once be removed by themselves, or to depend for these things so essential to their happinesse and freedom, upon the uncertain judgements of several Representatives, the one being apt to renew what the other hath taken away.

And as to the use of their Rights and Liberties herein as becometh, and is due to the people, from whom all just powers are derived; they hoped for and expect what protection is in you and the Army to afford: and we likewise in their and our own behalfs do earnestly desire, that you will publikely declare your resolution to protect those who have not forfeited their liberties in the use thereof, lest they should conceive that the Agreement before you being published abroad, and the Commissioners therein nominated being at work in persuance thereof, is intended to be imposed upon them, which as it is absolutely contrary to the nature of a free Agreement, so we are perswaded it cannot enter into your thoughts to use any impulsion therein.

But although we have presented our apprehensions and desires concerning this great work of an Agreement, and are apt to perswade our selves that nothing shall be able to frustrate our hopes which we have built thereupon; yet have we seen and heard many things of late, which occasions not only apprehensions of other matters intended to be brought upon us of danger to such an Agreement, but of bondage and ruine to all such as shall pursue it.

Insomuch that we are even agast and astonished to see that notwithstanding the productions of the highest notions of freedom that ever this Nation, or any people in the world, have brought to light, notwithstanding the vast expence of blood and treasure that hath been made to purchase those freedoms, notwithstanding the many eminent and even miraculous Victories God hath been pleased to honour our just Cause withall, notwithstanding the extraordinary gripes and pangs, this House hath suffered more than once at the hands of your own servants, and that at least seemingly for the obtaining these our Native Liberties.

When we consider what rackings and tortures the People in general have suffered through decay of Trade, and deernesse of food, and very many families in particular, through Free-quarter, Violence, and other miseries, incident to warre, having nothing to support them therein, but hopes of Freedom, and a well-setled Common-wealth in the end.

That yet after all these things have bin done and suffered, and whilst the way of an Agreement of the People is owned, and approved, even by your selves, and that all men are in expectation of being put into possession of so deer a purchase; Behold! in the close of all, we hear and see what gives us fresh and pregnant cause to believe that the contrary is really intended, and that all those specious pretenses, and high Notions of Liberty, with those extraordinary courses that have of late bin taken (as if of necessity for liberty, and which indeed can never be justified, but deserve the greatest punishments, unless they end in just liberty, and an equal Government) appear to us to have bin done and directed by some secret powerful influences, the more securely and unsuspectedly to attain to an absolute domination over the Common-wealth: It being impossible for them, but by assuming our generally approved Principles, and hiding under the fair shew thereof their other designs, to have drawn in so many good and godly men (really aiming at what the other had but in shew and pretense) and making them unwittingly instrumental to their own and their Countries Bondage.