Tracts on Liberty by the Levellers and their Critics Vol. 1 (1638-1843)

1st Edition (uncorrected)

Note: This volume has been corrected and is available here </titles/2597>.

This volume is part of a set of 7 volumes of Leveller Tracts: Tracts on Liberty by the Levellers and their Critics (1638-1659), 7 vols. Edited by David M. Hart and Ross Kenyon (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2014). </titles/2595>.

It is an uncorrected HTML version which has been put online as a temporary measure until all the corrections have been made to the XML files which can be found [here](/titles/2595). The collection will contain over 250 pamphlets.

- Vol. 1 (1638-1843): 11 titles with 1,562 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-1>

- Vol. 2 (1644-1645): 12 titles with 564 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-2>

- Vol. 3 (1646): 22 titles with 854 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-3>

- Vol. 4 (1647): 18 titles with 2,011 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-4>

- Vol. 5 (1648): 30 titles with 1,078 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-5>

- Vol. 6 (1649): 27 titles with 277 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-6>

- Vol. 7 (1650-1660): 42 titles with 1,055 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-7>

- Addendum Vol. 8 (1638-1646): 33 titles with 1,858 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-8>

- Addendum Vol. 9 (1647-1649): 47 titles with 2,317 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-9>

To date, the following volumes have been corrected:

- Vol. 1 (1638-1643) </titles/2597>

- Vol. 2 (1644-1645) </titles/2598>

- Vol. 3 (1646) </titles/2596>

Further information about the collection can be found here:

- Introduction to the Collection

- Titles listed by Author

- Combined Table of Contents (by volume and year)

- Bibliography

- Groups: The Levellers

- Topic: the English Revolution

2nd Revised Edition

A second revised edition of the collection is planned after the conversion of the texts has been completed. It will include an image of the title page of the original pamphlet, its location, date, and id number in the Thomason Collection catalog, a brief bio of the author, and a brief description of the contents of the pamphlet. Also, the titles from the addendum volumes will be merged into their relevant volumes by date of publication.

Leveller Tracts, Tracts on Liberty by the Levellers and their Critics, Volume 1, 1638-1640

Table of Contents:

- 1.1. John Liburne, The Christian Mans Triall (12 March 1638).

- 1.2. John Liburne, A Light for the Ignorant (1638).

- 1.3. John Liburne, A Worke of the Beast (1638).

- 1.4. [William Walwyn], A New Petition of the Papists (September 1641).

- 1.5. Robert Greville, A Discourse opening the Nature of that Episcopacie (November 1641).

- 1.6. Henry Parker, Observations upon some of his Majesties late Answers and Expresses (2 July 1642).

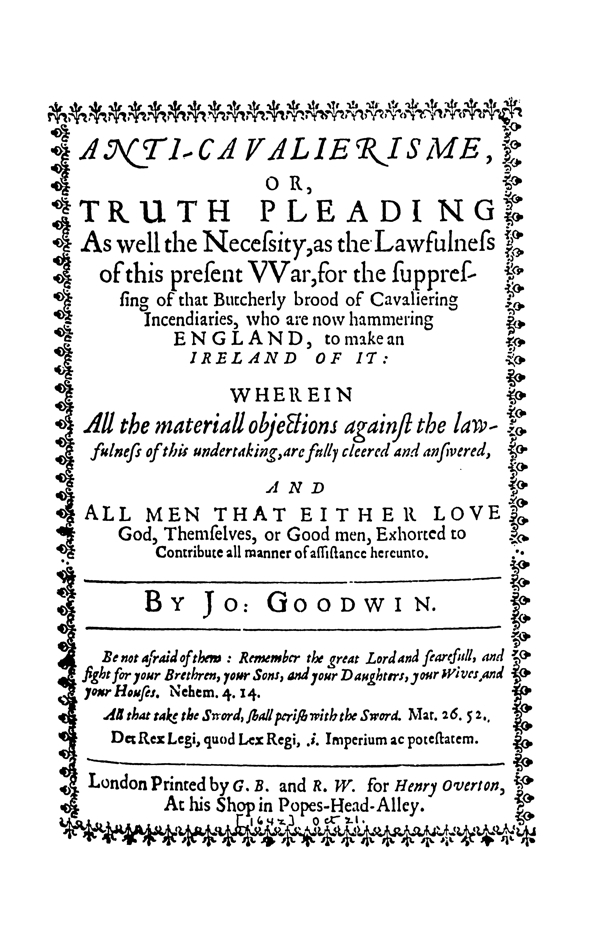

- 1.7. John Goodwin, Anti-Cavalierism, (12 October, 1642).

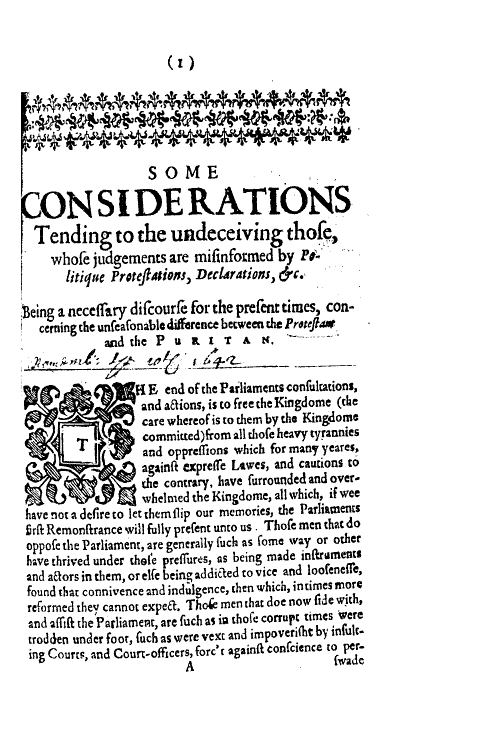

- 1.8. [William Walwyn], Some Considerations Tending to the Undeceiving (10 November 1642).

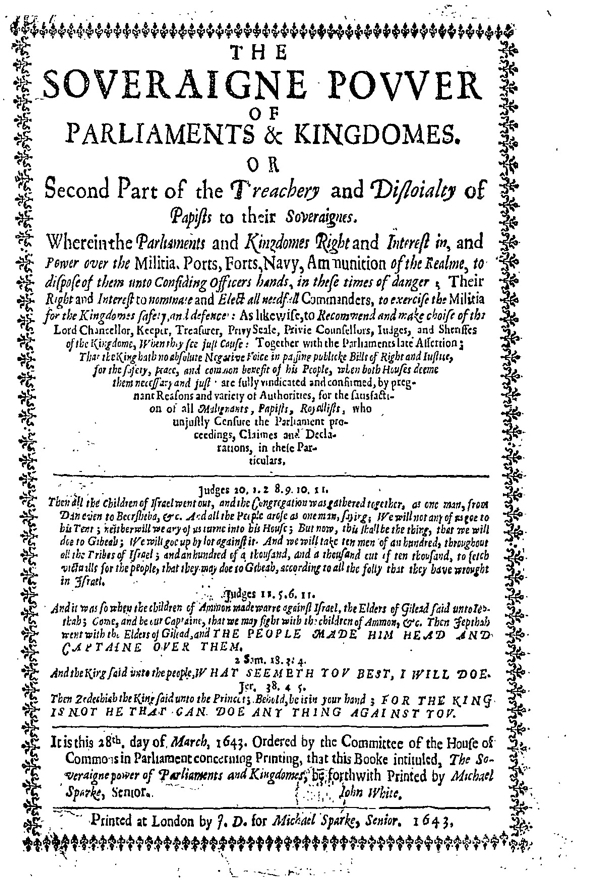

- 1.9. William Prynne, The Soveraigne Power of Parliaments and Kingdomes (15 April 1643).

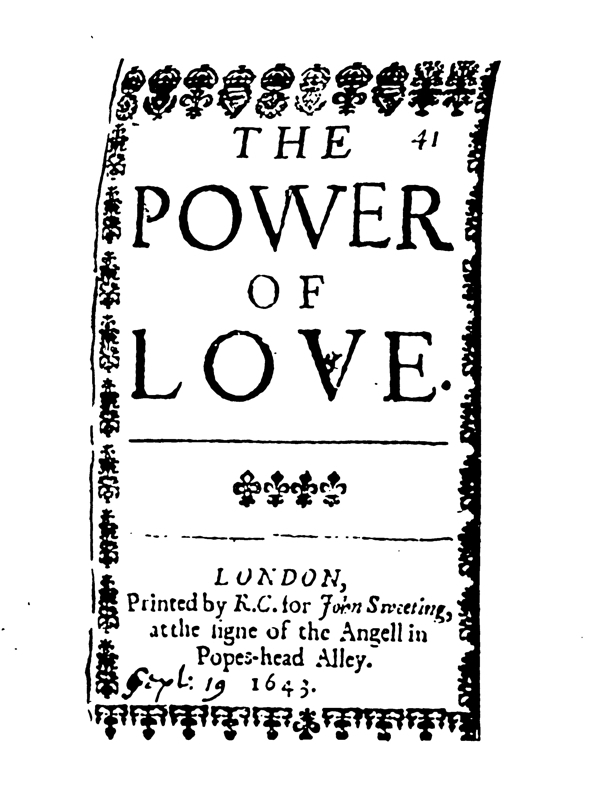

- 1.10. [William Walwyn], The Power of Love (19 September 1643).

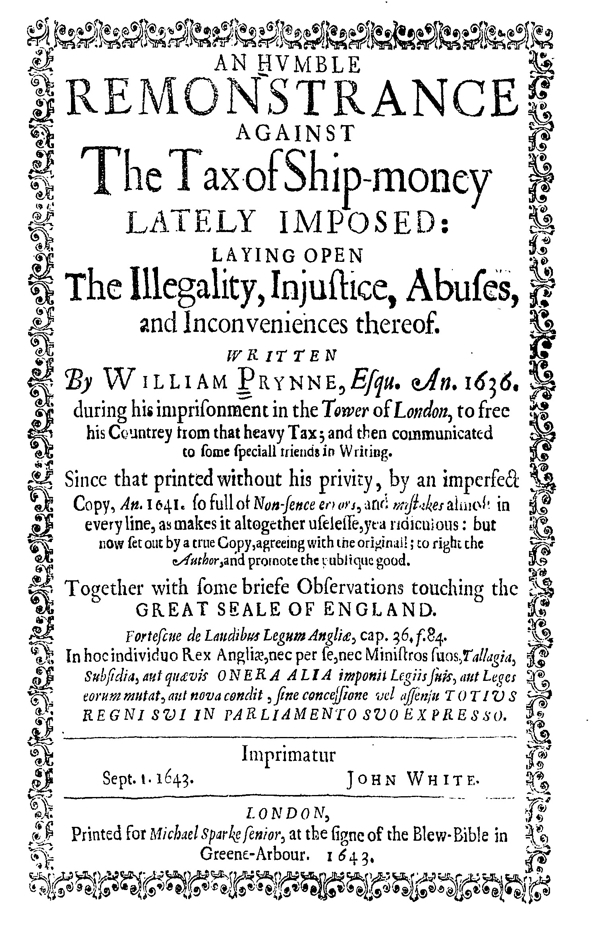

- 1.11. William Prynne, An Humble Remonstrance against The Tax of Ship-money (7 October 1643).

1.1. ↩

John Liburne, The Christian Mans Triall (12 March 1638).↩

THE CHRISTIAN MANS

TRIALL:

OR,

A TRUE REVELATION

of the first apprehension and severall examinations of JOHN LILBURNE,

With his Censure in Star-Chamber, and the manner of his cruell whipping through

the Streets: Whereunto is annexed his Speech in the Pillory, and their gagging of

him:

Also the severe Order of the Lords made the same day for fettering his hands and

feet in yrons, and for keeping his friends and monies from him, which was

accordingly executed upon him for a long time together by the Wardens of the Fleet,

with a great deale of barbarous cruelty and inhumanity, etc.

Revel. 2. 10. Behold, the Divell shall cast some of you into prison, that you may be

tryed, and you shall have tribulation ten dayes; be thou faithfull unto death, and

I will give thee a Crowne of life.

Matth. 10. 19. But when they deliver you up, take no thought how, or what you shall

speake; for it shall be given you in that houre what you shall say.

The second Edition, with an addition.

LONDON,

Printed for WILLIAM LARNAR, and are to be sold at his Shop at the Signe of the

Golden Anchor, neere Pauls-Chaine, 1641.

TO THE READER.

CHristian Reader, here is presented to thy view, a part of these cruell and grievous sufferings imposed upon this Author, by the malignant malice of the Prelacy and that faction, wherein thou mayest likewise see the wonderfull gracious dealings of a good God, carrying this Author through them all, with boldnesse and courage, being not daunted, neither at their frownes nor whippings, nor pilpriesignor closee prisons, no nor yrons; so that we may see the faithfull promise of our God before our eyes made good in this young man, who hath promised to be with his people in six troubles, and seven; and to hew himselfe strong in the behalfe of all those whose hearts are perfect before him, that so hee might out of the mouthes of Babes and Sucklings perfect his owne praise, to the astonishment of all those who shall lift up heart or hand against him, or the least of his holy ones; and to the comfort and encouragement of all the Saints, who, from the consideration of the sweet, supporting power of God, appearing to others in their bonds, are the more encouraged publiquely to hold forth their profession of the truths of the Lord Iesus with much more boldnesse and confidence, as knowing that that God which hath appeared to others of the Saints in times of offerings, even before their eyes, will also appeare to them in the like condition; and therefore wee may a little see and take notice of the follyes of wicked mens wisdomes, who thinke by their hellish wits, to raze downe Syon and the truth of God to the ground, and therefore they labour by the imprisonments and tortures of some to dash the rest out of heart, that they should feare to shew any countenance to such a persecuted way, whereas indeed the Saints have by this meanes a fairer object to pitch their faith and confidence upon, namely, the power and wisedome and grace and mercy of their God appearing in a more fuller vision before their eyes; for the afflictions and persecution that are imposed by wicked men upon the Saints, causeth them to see a Spirit of glory resting upon them, even in this condition: here 1 Pet. 4. 13. 14. and a massive weight of glory provided for them hereafter, 1 Cor. 4. 18. So that we may daily see the God of heaven fulfilling of his owne Word, even in this thing, which is that hee will confound the wisedome of the wise, and bring to nought the understanding of the prudent, and catch the wicked in their owne snares, making the rage of man turne to his owne praise his peoples comforts and their ruins, wherefore let the servants of God comfort one another with these words: That we may not feare the feares of men, which, that we may be the more strengthened against them, let us consider the cloud of witnesses which hath gone before in a way of suffering, even in these our times, amongst whom the Author of this booke hath had his share with the deepest of them, and therefore to this end hath he published to the world this Truth, that he might keepe alive to all posterities the goodnesse, and mercy and love of God manifested to him under those cruell barbarous and tyrannical dealings of the prelaticall hierarchie, that so all the Saints of God may hate that wicked calling and power of theirs, and never give over crying to God and men, till it be razed downe to the ground, that so the Lord Iesus may be set up as Lord and King, which ought to be the desire and endeavour of all the chosen ones of God, and is the desire of him who desires the good of the servants of God, in all things, love for Christ.

WILLIAM KIFFEN

This is the first Part.

A CHRISTIAN MANS TRIALL.

VPon Tuesday last the 11 or 12 of December, 1637 I was treacherously and Judasly betraied (by one that I supposed to be my friend) into the hands of the Pursevant with foure of his assistants, as I was walking in a narrow lane, called Super-lane, being walking with one Iohn Chilliburne, servant to old Mr. Iohn Wharton, in Bow-lane a Hotpresser. Which Iohn had laid the plot before for my apprehension, as I am able for to prove and make good, that he shall not be able with truth to deny it. And at my taking the Pursevants were very violent cries and having by force got me into a shop, they threw me over a Sugar-chest, to take my Sword from me, and cried out for helpe, and said he had taken one of the notoriousest dispersers of scandalous bookes that was in the Kingdome, for (saith he) he hath dispersed them from one end of the Land to the other.

And from thence I was had to the Bole-head Taverne neere to the Dr. Commons, where the Pursevants called freely for wine to make themselves merry, thinking they had got a great prise; Being not long there with my Pursevant Flamsted, who apprehended me, in came Beniragge, the great Prelates Pursevant, and he looking upon me, said Mr. Lilburne, I am glad with all my heart that wee are met, for you are the man that I have much desired for a long time to see. To which I replied are you so? And for my owne part, I am not much unglad, But you thinke, you have got a great purchase in taking me, but it may be you may be deceived. Come (saith he) give us some wine, and with that he swore an Oath, he would give me a quart of Sacke, for joyfulnesse of our meeting, and so he called for it and dranke to me: And I told him, I would drinke no wine. To which hee replied, and said in these words: Come (said he) be not sad, you are but fallen into the Knaves hands. To which I said, I am not sad in the least, and for my falling into Knaves hands, I verily beleeve without any questioning, that which you have said. And then he swore another Oath, and said, it was true enough.

(So good Christian Reader, take notice of thus much by the way, that the Prelates and their Creatures are a company of Knaves by Beniragge his own Confession.)

That night I was kept at Hamstedds house where I blesse God, I was merry and cherefull, and nothing at all danted at that which had befalne me. And about twelve of the clocke the next day, I was committed to the Gatehouse, by Sir John the Prelate of Canterburies Chancellour with others without any examination at all, for sending of factious and scandalous Bookes out of Holland into England. And having not beene at the foresaid prison above three dayes, I was removed, by a Warrant from the Lords of the Counsell to the Fleet, where I now remaine. And after my being there some time, I drew a Petition to the Lords of the Counsell for my liberty: and their answer to it was, that I should be examined before Sir John Bankes, the Kings Atturney: The Coppy of which examination thus followes.

Upon Tuesday, the 14 of Ianuary, 1637 I was had to Sir John Bankes the Attorney General’s Chamber (now Lord chiefe Justice of the Court of Pleas) and was referred to be examined by Mr. Coilibey his chief Clerke; And at our first comming together, he did kindly intreat me; and made me sit downe by him, and put on my hat, and began with me after this manner: Mr. Lilburne, what is your Christian name? I said, Iohn, Did you live in London before you went into Holland? Yes, that I did. Where? Neare Londonstone. With whom there? With Mr. Thomas Hewson. What Trade is he? A dealer in Cloath, I told him. How long did you serve him? About five yeares. How come you to part? After this manner: I perceiving my Master had an intention to desist his Trade, I often moved him that I might have my liberty, to provide for my selfe, and at the last hee condescended unto it; and so I went into the Country, to have the consent of my friends; and after that departed into Holland. Where were you there? At Rotterdam. And from thence you went to Amsterdam? Yes, I was at Amsterdam. What Bookes did you see in Holland? Great store of Bookes, for in every Bookesellers shop as I came in, there were greate store of Bookes. I know that, but I aske you, if you did see Dr. Bastwicks Answer to my Masters Information and a Book called his Letany? yes, I saw them there, and if you please to goe thither. you may buy an hundred of them at the Bookesellers, if you have a minde to them Have you seene the Unbishopping of Timothy and Titus, the Looking glasse, and a Breviate of the Bishops late proceedings. Yes, I have, and those also you may have there, if you please to send for them. Who Printed all those Bookes? I doe not know. Who was at the charges of Printing of them? Of that I am ignorant. But did you not send over some of these Books? I sent not any of them over. Doe you know one Hargust there? Yes, I did see such a man. Where did you see him? I met with him one day accidentally at Amsterdam. How oft did you see him there? Twise upon one day. But did not he send over Bookes? If he did, it is nothing to me, for his doings is unknowne to me. But he wrote a Letter over by your directions, did he not? What he writ, I know no more than you. But did you see him nowhere else there? Yes, I saw him at Rotterdam. What conference had you with him? Very little; But why doe you aske me all these questions; These are besides the matter of my imprisonment, I pray come to the thing for which I am accused, and imprisoned. No, these are not besides the businesse, but doe belong to the thing for which you are imprisoned. But doe you know of any that sent over any Bookes? What other men did, doth not belong to me to know or search into, sufficient it is for me to looke well to my owne occasions. Well, here is the examination of one Edmond Chilington, doe you know such a one? Yes. How long have you beene acquainted with him? A little before I went away, but how long I doe not certainely know: Doe you know one Iohn Wharton? No. Doe you not, he is a Hot-presser: I know him, but I doe not well remember his other name: How long have you beene acquainted with him: And how came you acquainted? I cannot well tell you: How long doe you thinke? I doe not know: What speeches had you with Chillington since you came to Towne? I am not bound to tell you: But Sir (as I said before) why doe you aske me all these questions, these are nothing pertinent to my imprisonment for I am not imprisoned for knowing and talking with such and such men: But for sending over Bookes: And therefore I am not willing to answer you to any more of these questions because I see you goe about by this examination to insnare mee, for seeing the things for which I am imprisoned cannot be proved against me, you would get other matter out of my examination, and therefore if you will not aske me about the thing laid to my charge, I shall answer no more: but if you will aske me of that I shall then answer you, and doe answer, that for the thing for which I am imprisoned, which is for sending over Bookes, I am cleare for I sent none. And of any other matter that you have to accuse me of, I know it is warrantable, by the Law of God, and I thinke by the Law of the Land, that I may stand upon my just defence, and not answer to your intergatorie; and that my accusers ought to be brought face to face to justifie what they accuse me of; And this is all the answer that for the present I am willing to make: And if you aske me of any more things I shall answer you with silence. At this he was exceeding angry, and said: There would be course taken with me to make me answer. I told him, I did not way what course they would take with me; onely this I desire you to take notice of: that I doe not refuse to answer out of any contempt but onely because I am ignorant what belongs to an examination, (for this is the first time that ever I was examined) and therefore I am unwilling to answer to any impertinent questions for feare that with my answer I may doe my selfe hurt. This is not the way to get liberty. I had thought you would have answered punctually that so you might have beene dispatched as shortly as might be. So I have answered punctually to the thing for which I am imprisoned and more I am not bound to answer, and for my liberty I must waite Gods time. You had better answer, for I have two examinations wherein you are accused. Of what am I accused? Chillington hath accused you for printing ten or twelve thousands of Books in Holland, and that they stand you in about eighty pound, and that you had a Chamber at Mr. Iohnfoots at Delft, where he thinks the Bookes were kept, and that you would have printed the Vnmasking of the Mystery of Iniquity, if you could have got a true Copy of it. I doe not beleeve that Chillington said any such things and if he did, I know, and am sure, that they are all of them lies. You received money of Mr. Wharton since you came to Towne, did you not? What if I did? It was for Bookes? I doe not say so. For what sorts of bookes was it? I doe not say it was for any, and I have already answered you all, that for the present I have to answer and if that will give you content, well and good, if not, doe what you please. If you will not answer no more (here I told him if I had thought you would have insisted upon such impertinent questions, I would not have given him so many answers) wee have power to send you to the place from whence you came. You may doe your pleasure, said I. So hee called in anger for my Keeper, and gave him a strict charge to looke well to me. I said they should not feare my running away. And so I was sent down to Sir Iohn Bankes himself. And after that he had read over what his man had writ he called me in, and said, I conceive you are unwilling to confesse the Truth. No Sir, I have spoken the Truth. This is your Examination, is it not? What your man hath writ I doe not know. Come neare and see that I read it right. Sir, I doe not owne it for my Examination for your man hath writ what it pleased him, and hath got writ my answer, for my answer was to him, and so is to you, that for the thing for which I am imprisoned (which is for sending over bookes) I am cleare, for I did not send any, and for any other matter that is laid to my charge, I know it is warrantable by the Law of God, and I thinke by the Law of the Land, for me to stand upon my just defence, and that my accusers ought to be brought face to face, to justifie what they accuse me of. And this is all that I have to say for the present. You must set your hand to this your Examination. I beseech you Sir pardon me, I will set my hand to nothing but what I have now said. So he tooke the Pen and writ, the examined is unwilling to answer to any thing but that for which hee is imprisoned. Now you will set your hand to it? I am not willing in regard I doe not owne that which your man hath writ, but if it please you to lend me the Pen, I will write my Answer, and set my hand to it. So he gave mee the Pen, and I begun to write thus: The Answer of me Iohn Lilburne is, And here hee tooke the Pen from me, and said he could not stay, that was sufficient. Then one of my Keepers asked him if they might have me backe againe? And he said yea: for he had no Order for my inlargement, and so I tooke my leave of him, and desired the Lord to blesse and keepe him, and came away.

And then about ten or twelve dayes after, I was had forth to Grayes Inne againe, but when I went, I did not know what they would doe with me there: And when I came there, I was had to the Starre-Chamber Office; and being there, as the Order is, I must enter my appearance, they told me, I said, to what, for I was never served with any Subpoena; neither was there any Bill preferred against me4 that I did heare of. One of the Clarkes told me, I must first be examined, and then Sir Iohn would make the Bill: it seemes they had no grounded matter against me for to write a Bill, and therefore they went about to make me betray my owne innocency, that so they might ground the Bill upon my owne words: but my God shewed his goodnesse to me, in keeping me, (a poore weake worme) that they could not in the least intangle mee, though I was altogether ignorant of the manner of their proceedings: And at the entrance of my appearance, the Clarke and I had a deale of pritty discourse; the particulars whereof for brevity sake I now pretermit but in the conclusion he demanded mony of me for entring of my appearance: and I told him I was but a young man, and a prisoner, and money was not very plentifull with me and therefore I would not part with any money upon such termes. At which answer the man began to wonder that I should speake so to him and with that the whole company of the Clarkes in the Office began to looke and gaze at me. Well (said he) if you will not pay your fee I will dash out your name againe. Doe what you please (said I) I care not if you doe. So he made a complaint to Mr. Goad, the Master of the Office, that I refused to enter my appearance. And then I was brought before him, and he demanded of me what my businesse was? I told him, I had no businesse with him, but I was a prisoner in the Fleete, and was sent for but to whom and to what end I doe not know, and therefore if he had nothing to say to me, I had no businesse with him. And then one of the Clarks said, I was to be examined. Then Mr. Goad said, tender him the booke. So I looked another way, as though I did not give eare to what he said; and then he bid me pull off my glove, and lay my hand upon the booke, What to doe Sir? said I. You must sweare said he. To what? That you shall make true answer to all things that is asked you. Must I so Sir? But before I sweare, I will know to what I must sweare. As soon as you have sworne, you shall, but not before: To that I answered. Sir, I am but a young man, and doe not well know what belongs to the nature of an Oath, and therefore before I sweare, I will be better advised. Saith he, how old are you? About twenty yeares old, I told him. You have received the Sacrament, have you not? Yes that I have. And you have heard the Ministers deliver Gods Word, have you not? Yes, I have heard Sermons. Well then, you know the holy Evangelist? Yes that I doe. But Sir, though I have received the Sacrament, and have heard Sermons, yet it doth not therefore follow that I am bound to take an Oath, which I doubt of the lawfulnesse of. Looke you here, said he; and with that he opened the booke, we desire you to sweare by no forraigne thing, but to sweare by the holy Evangelist. Sir, I doe not doubt or question that onely I question how lawfull it is for me to sweare to I do not know what. So some of the Clarks began to reason with me, and told me everyone tooke that Oath; and would I be wiser than all other men? I told them, it made no matter to me what other men doe; but before I sweare, I will know better grounds and reasons than other mens practises to convince mee of the lawfulnesse of such an Oath, to sweare I doe not know to what. So Mr. Goad bid them hold their peace, he was not to convince any mans conscience of the lawfulnesse of it, but onely to offer and tender it; Will you take it or no, saith he? Sir, I will be better advised first; with this there was such looking upon mee, and censuring me for a singular man, for the refusing of that which was never refused before: whereupon there was a Messenger sent to Sir Iohn Bankes, to certifie him, that I would not take the Star-Chamber Oath. And also to know of him what should be done with me. So I looked I should be committed close prisoner or worse. And about an houre after came Mr. Cockshey, Sir Iohns chiefe Clarke, what (said he) Mr. Lilburne, it seems you will not take your Oath, to make true answer? I told him, I would be better advised before I took such an Oath, Well then (saith he) you must goe from whence you came and then I spoke merrily to my Keepers, and bid them, let us be gone, we have beene long enough here. Thus have I made a true Relation of that dayes worke.

But before I proceede, I desire to declare unto you, the Lords goodnesse manifested unto me in being my counsellour and director in my great straights. The Prelates intendment towards me was carried so close that I could not learne what they would doe with me, onely I supposed they would have mee into the Star-chamber, in regard I was removed by the Lords of the Counsell; and also tidings was brought unto me by some friends, what cruelty their Creatures did breath out against me, but I incouraged my selfe in my God, and did not feare what man could doe unto me, Esay 51, 12, 13, for I had the peace of a good conscience within me, and the assurance of Gods love reconciled unto me in the precious blood of his Sonne JESVS CHRIST: which was as good as Shield and Buckler unto me, to keepe off all the assaults of my enemies, and I was, as it were, in a strong walled Towne, nothing dreading but lightly esteeming the cruelty of my Adversaries, for I knew God was my God, and would be with me, and inable me to undergoe whatsoever, by his permission they could inflict upon me, and to his praise I desire to speak it: I found his gracious goodnesse and loving kindnes so exceedingly made known unto me, that he enabled me to undergoe my captivity with contentednesse, joyfulnesse, and cherefulnesse: And also was pleased, according to his promise, to be a mouth unto me, whensoever I was brought before them, and gave me courage and boldnesse to speake unto them, his holy and blessed name be praised and magnified for it.

Vpon the Fryday next, after this, in the morning, one of the Officers of the Fleete came to my Chamber, and bid mee get up and make mee ready to goe to the Star-Chamber barre forthwith, I having no time to fit my selfe, made me ready in all haste to goe; (yet when I came there, the Lord according to his promise was pleased to be present with me by his speciall assistance, that I was inabled without any dantednesse of spirit, to speake unto that great and noble Assembly, as though they had beene but my equalls;) And being at the barre, Sir Iohn Bankes laid a verball accusation against me, which was, that I refused to answer, and also to enter my appearance, and that I refused to take the Star-Chamber Oath: and then was read the Affidavit of one Edmond Chillington, Buttonseller, made against Mr. Iohn Warton and my selfe; The summe of which was, that he and I had Printed at Rotterdam in Holland Dr. Bastwickes answer, and his Letany, and divers other scandalous Bookes. And then after I had obtained leave to speake, I said: My noble Lords, as for that Affidavit, it is a most false lie, and untruth. Well, said the Lord-keeper, why will you not answer? My Honorable Lord (said I) I have answered fully, before Sir Iohn Bankes to all things that belongs to me to answer unto, and for other things, which concerne other men, I have nothing to doe with them. But why doe you refuse to take the Star-Chamber Oath? Most Noble Lord, I refused upon this ground, because that when I was examined, though I had fully answered all things that belonged to me to answer unto, and had cleared my selfe of the thing for which I am imprisoned, which was for sending bookes out of Holland, yet that would not satisfie and give content, but other things was put unto me, concerning other men, to insnare me, and get further matter against me, which I perceiving refused, being not bound to answer to such things as doe not belong unto me; and withall I perceived the Oath to be an Oath of inquiry; and for the lawfulnesse of which Oath I have no warrant, and upon these grounds I did, and doe still refuse the Oath: with this some of the Kings Counsell, and some of the Lords spoke, would I condemne and contradict the Lawes of the Lands and be wiser than all other men to refuse that, which is the Oath of the Court, administred unto all that come there? Well, said my Lord-Keeper, render him the booke. I standing against the Prelate of Canterburies backe, he looked over his shoulder at me & bid me pull off my glove, and lay my hand upon the book. Unto whom I replied, Sir, I will not sweare; and then directing my speech unto the Lords, I said: Most Honorable and Noble Lords, with all reverence and submission unto your Honours, submitting my body unto your Lordships pleasure, and whatsoever you please to inflict upon it yet must I refuse the Oath. My Lords, said the Arch Prelate (in a deriding manner) doe you heare him, hee saith, with all reverence and submission he refuseth the Oath. Well, come come (said my Lord Keeper) submit your selfe unto the Court. Most Noble Lords, with all willingnesse I submit my body unto your Honours pleasure, but for any other submission, most Honourable Lords, I am conscious unto my selfe, that I have done nothing, that doth deserve a convention before this illustrious Assembly and therefore for me to submit is to submit I doe not know wherefore. With that up stood the Earle of Dorset, and said: My Lords, this is one of their private spirits; Doe you heare him, how he stands in his owne justification? Well my Lords, said the great Prelate; this fellow (meaning me) hath been one of the notoriousest disperser of Libellous bookes that is in the Kingdome, and that is the Father of them all (pointing to old Mr. Wharton.) Then I replied, and said, Sir, I know you are not able to prove and to make that good which you have said. I have testimony of it, said he. Then said I produce them in the face of the open Court, that wee may see what they have to accuse me of; And I am ready here to answer for my selfe, and to make my just defence. With this he was silent and said not one word more to me: and then they asked my fellow Souldiour old Mr. Wharton, whether he would take the Oath, which hee refused, and began to tell them of the Bishops cruelty towards him, and that they had had him in five severall prisons within this two yeares, for refusing the Oath. And then there was silence, after which was read a long peece of businesse how the Court had proceeded against some that had harboured Jesuits and Seminary Priests (those Traitors) who refused to be examined upon Oath, and in regard that we refused likewise to be examined upon Oath, it was fit they said, that we should be proceeded against, as they were, so they were the president by which we were censured, though their cause and ours be much unlike, in regard theirs were little better than Treason; but our crime was so farre from Treason, that it was neither against the glory of God, the honour of the King, the Lawes of the Land, nor the good of the Commonwealth: but rather for the maintaining of the honour of them all, as all those that read the bookes without partiall affections, and prejudicate hearts, can witnesse and declare, and if the bookes had had any Treason, or any thing against the Law of the Land in them, yet we were but subposedly guilty, for the things were never fully proved against us; indeed there was two Oathes read in court, which they said was sworne against us by one man but he was never brought face to face, and in both his Oathes he hath forsworne himselfe, as in many particulars thereof wee both are able to make good. In the conclusion, my Lord Keeper stood up and said, My Lords, I hold it fit, that they should be both for their contempt committed close prisoners till Tuesday next; and if they doe not conforme themselves betwixt this and then to take the Oath, and yeeld to be examined by Mr. Goad, then that they shall be brought hither againe, and censured, and made an Example; Unto which they all agreed; and so we were committed close prisoners, and no friends admitted to come unto us.

And upon Munday after we were had to Grayes Inne, and I being the first there, Mr. Goad said to me, according to the Lords Order upon Friday last, I have sent for you to tender the Oath unto you. Sir, I beseech you, let me heare the Lords Order. So he caused it to be read unto mee, and then tendered mee the Booke. Well Sir, said I, I am of the same minde I was, and withall I understand, that this Oath is one and the same with the High Commission Oath, which Oath I know to be both against the Law of God, and the Law of the Land; and therefore in briefe I dare not take the Oath, though I suffer death for the refusall of it. Well, said he, I did not send for you to dispute with you about the lawfulnesse of it, but onely according to my place to tender it unto you. Sir, I dare not take it, though I loose my life for the refusall of it. So he said, he had no more to say to me; and I tooke my leave of him and came away. And after that came the old Man, and it was tendered unto him, which he refused to take: (and as he hath told me) he declared unto him how the Bishops had him eight times in prison for the refusall of it, and he had suffered the Bishops mercilesse cruelty for many yeares together, and he would now never take it as long as he lived; and withall told him, that if there were a Cart ready at the doore to carry him to Tiburne, he would be hanged, before ever hee would take it. And this was that dayes businesse.

Upon the next morning about seven a clocke, we were had to the Star-Chamber-bar againe to receive our Censure; and stood at the Bar about two houres before Sir Iohn Bancks came; but at the last hee began his accusation against us, that we did still continue in our former stubbornenesse: and also there was another Affidavit of the foresaid Edmond Chillingtons read against us, the summe of which was that I had confessed to him that I had printed Dr. Bastwickes Answer to Sir Iohn Bancks his Information, and his Letany; and an other booke, called, An Answer unto certaine Objections; and another booke of his, called the Vanitie and Impiety of the old Letany; and that I had divers other bookes of Dr. Bastwickes a Printing; and that Mr. Iohn Wharton had beene at the charges of Printing a booke called A breviate of the Bishops late proceedings; and an other booke, called Sixteene new Queries, and divers other factious bookes; and that one James Ouldam, a Turner in Westminster-Hall, had dispersed divers of these bookes. So it came to me to speake; and I said after this manner: Most Noble Lords, I beseech your Honours, that you would be pleased to give me leave to speake for my selfe, and to make my just defence; and I shall labour so to Order my speeches, as that I shall not give your Honours any just distaste; and withall shall doe it with as much brevitie as I can. So having obtained my desire, I began, and said, My Lords, it seemes there was divers bookes sent out of Holland, which came to the hands of one Edmond Chillinton, which made this affidavit against us: and as I understand, he delivered divers of these bookes unto one Iohn Chilliburne, servant to this old Man Mr. Wharton (I, said he, my Lords, and I had given him a strict charge, that he should not meddle with any,) and his Master being in Prison, he dispersed divers of them for the foresaid Chillingtons use, whereupon the bookes were taken in his Custody, and he being found dispersing of them, gos to one Smith, a Taylor in Bridewell (as I am informed) & desires him to get his peace made with the Bishops, whereupon he covenants with some of the Bishops Creatures, to betray me into their hands, being newly come out of Holland, which (as he said) did send over these bookes. So my Lords, he having purchased his owne libertie, layes the plot for betraying me, and I was taken by a Pursevant and foure others of his assistance, walking in the streets with the foresaid Iohn Chilliburne, who had laid and contrived the plot before (as I am able to make good) and the next morning I was committed by Sir Iohn Lamb to the Gate-house, (now my Lords, I doe protest before your Honours in the word of a Christian, that I did not send over these bookes, neither did J know the Ship that brought them, nor any that belongs to the ship, nor to my knowledge did never see with my eyes, either the ship or any that belongs unto it.

(But before I proceede with my Speech, I desire to digresse a little, in regard that Iohn Chilliburne doth yet stifly maintaine, that he did not betray me, nor laid the plot, and therefore I doe him wrong for accusing him, he saith. To which I answer, and say, in this, he is worse than Iudas himselfe; for after he had betrayed Christ, he came and confessed his sinne, and said, I have sinned in betraying the innocent blood; and this man hath betraied Christ in betraying me his member, for what is done to his servant he takes it as done to himselfe: but he is not so good as Iudas, who confessed his fault, but he hides and justifies his sinne, and therefore I will declare my Grounds and Demonstrations, whereupon I am sure he was the Judas: The first is thus, He and I appointed to meete one day upon the Exchange at two a clocke, unto which place I came, and staid long for his comming, but hee came not: and I verily thinke, he sent two or three in his place, two of them being Arminians, living in Cornehill, which J my selfe knew, who passed againe and again by me, vewing very narrowly my apparell, visage and countenance, as J thinke for that end that they might know mee againe: and when J sat downe, they would passe by, and goe a little from me and sit downe and fix their eyes upon me, insomuch that J was afraid that J should there have been taken, which forced me to depart. And at our next meeting J told him of it, and how that (unlesse J had knowne him well) J should have beleeved he had betrayed me. Unto which hee gave me no satisfactory answer, but put it off, and said his libertie was as precious as mine; and if he should betray me, he must betray himselfe, and therefore J needed not to doubt any such thing: the Lord having blinded my eyes. J could not see into his treacherous heart, but tooke this for a currant answer, J knowing that he had had a deepe hand in the dispersing of bookes, and therefore J gave credite to that which he had said, as being a reall Truth, the Lord having a secret hand of providence in it. (J hope at the last for his glorie and my good) did so Order it, that I should not take notice, or perceive his perfidiousnesse, though I had an incling given me of it before by some friends, yet J could not beleeve it till the event manifested it, for that day J was taken, he hearing (by what meanes I doe not know) that I was to meete one at the Temple, and understanding that I had a desire to see his Master at his owne houre (being newly let out of prison) we came towards the Temple, and had some discourse there, in which he put me forward to goe see and speake with his Master, unto whom I declared, how fearefull I was to goe thither (in regard I heard they laid waite for me) least I should be taken; but he made all things cleare, and contrived a way, by meanes of which he said, I might without any feare goe speake with him. So we parted, and appointed to meete at the staires that goes from Bridewell to Black-Fryers. I came to the Staires, and stood a great while, but he came not, till I was a comming away; and I expecting him to come out of Bridewell, I having sent him in thither, to speake with one, unto whom I thinke he did not goe, but yet he told me, he was with him; but rather he went to Flamsted the Pursevant to get him in a readinesse, for he came to me from Flamsteds-houseward, downe from Black-Fryers, being a cleane contrary way to that I sent him. So we went towards his Masters house, and parted againe, and appointed to meet at Tantlins-Church; and when I came there, I saw one walking with him, which I verily beleeve was one of the five that tooke me; and when I came to him, I declared unto him that comming downe Soper-lane, I saw a fellow stand in a corner, very suspiciously, who looked very wishfully at me, and I at him; and therefore I desired him to goe, and see who it was, and whether I might goe safely to his Masters or no. So he went, and came backe, and told me his Master was come to the doore, and I might goe without any danger, and as we went, I declared unto him my fearefulnesse, to goe to his Masters; and I told him, I would halfe draw my sword, that I might be in a readinesse; and he went before towards his Masters; and I doe verily thinke acquainted them how it was with me; and I going after him in the narrow Lane, I passed by two great fellowes suspecting nothing; and by and by they seazed upon my backe and shoulders, and cried out in the Kings Name for helpe, they had taken the Rogues Whartons men, and Iohn was the third man that seized upon me, laying fast hold of my left shoulder, and they three pulled my cloake crosse over my armes, that so, though I had my sword halfe drawne, yet by no meanes could I get it out; which if I had, and got my backe against the wall, I doe not doubt but I should have made them be willing to let me alone; for though they had fast hold of me, they quaked and trembled for feare, and though they were five or sixe, yet they cryed out for more helpe to assist them, I being but one, and when they all seased on me, then they called me by my name, and though we were in the darke, yet they knew my habit, that I was in as well as my selfe, and shewed me their warrant with my name in it I have beene forced of necessity to recite these things in regard of his dayly speeches against me, and his writing to me in justification of his innocency, though as you for all I have sent for him, hee would never come face to face: Tart Letters likewise I have received from Smith and Chillington, for speaking that which I have said in publique of them: and as for Smith, take notice what I said of him, and I here give my reasons for that I said, it is knowne that at the last time the bookes were taken at Mr. Whartons, part of them was not taken; which Iohn can not deny, but he carried them unto Smith, and what passed betwixt them, they themselves best knows but this is sure, Iohn was never troubled for the bookes, though hee was taken dispersing of them; and I am sure, his libertie was obtained by Smiths and Sam Bakers the Prelate of Londons Chaplaines meanes. Also Smith is not ignorant, but doth very well know that promise that Iohn made to Mr. Baker about twelve moneths agoe, to doe him speciall service about such things, which promise I doe verily beleeve he hath faithfully kept; for he hath confessed to his Master since the beginning of my trouble, that he hath used to carry to Baker all new bookes he could get, as soone as they came out, and how for the which he gave him money, but how much he best knowes.

Also, what free and familiar accesse Iohn hath had to him, and he and Iohn to Baker, and for those secrets which Iohn from time to time hath revealed to him and Baker, what they are I name not, but appeale to their owne consciences: for it is too manifest that hee is a darling both to Smith and Baker, in regard they stand so stoutly for him as they doe; for Mr. Wharton, being not long since with Baker, he told him hee heard he was about to put away his Man Iohn, Yea (said he) what should I do with him else? Well (said he) if you doe it, and put him away, the Chamberlaine will make you take him againe. Will he so (said he) he can not doe it, for he is a Iudas, and a Theefe, for he hath stolne money from me, and I can prove it said the Old Man; and therefore he can not make me take him againe. Baker could not well tell what to say to it; but yet did perswade him to keepe him.

This the Old man told me himselfe, it seemes they have kept him at his Masters, as a private and secret servant for their owne turnes above this fourteene Moneths, and they would still, if they could keepe him there. But what secret mischiefe hee hath done by his so frequent resorting to Baker and Smith, is not yet fully knowne, but I hope it will come out by degrees: Therefore, let all that heares of it take notice of it, and let some of those that were in the information with the three Worthies, cast back their eyes and see if they can finde and spie out who was their Originall Accuser and Betrayer. These things may be worth the making knowne, though I may incurre hatred and spite from them for it, yet I weigh not that, for I have not declared these things out of any revenge, for I commit that unto God.

And for that wrong they have done unto mee, I freely forgive them; and if any of them belong to God, I pray him to call them home unto him. But these things I have set downe, being forced thereunto for vindicating my good name from their bitter reproaches and calumniations, and all you that read this, judge and censure what I have said. But now after my Digression I will returne againe to our former matter.

And being at the Gatehouse I was removed by (sixe of your Honours) to the Fleete, at which time the said Chillington was removed from Bridewell to Newgate, and being kept close there: then he by their threats and perswasions and the procuring of his owne liberty, goes and accuses me for printing ten or twelve thousand Bookes in Holland. And at my Examination before Sir Iohn Bankes I cleared my selfe of that, and upon Fryday last he made an Affidavit against me, in which hee hath most falsly forsworne himselfe, and today he hath made another, which is also a most false untruth: And withall my Lords, he is knowne to be a notorious lying fellow, and hath accused mee for the purchasing of his owne liberty, which he hath got. And therefore, I beseech your Honours, to take into your serious consideration, and see whether I am to be censured upon such a fellowes Affidavits or no. Then said the Lord Keeper, thou art a mad fellow, seeing things are thus, that thou wilt not take thine Oath, and answer truely. My Honourable Lord, I have declared unto you the reall Truth, but for the Oath, it is an Oath of Inquiry, and of the same nature of the High-Commission-Oath; Which Oath I know to be unlawfull; and withall, I finde no warrant in the Word of God, for an Oath of Inquiry, and it ought to be the director of mee in all things that I doe, and therefore my Lords at no hand, I dare not take the Oath (when I named the Word of God, the Court began to laugh, as though they had had nothing to doe with it) my Lords (said Mr. Goad) he told me yesterday, he durst not take the Oath, though he suffered death for the refusall of it. And with that my Lord Privy Seal spoke: Will you (said he) take your Oath, that that which you have said is true? My Lord (said I) I am but a young Man, and doe not well know what belongs to the nature of an Oath (but that which I have said is a reall truth) but thus much by Gods appointment, I know an Oath ought to be the end of all controversie and strife, Heb. 6. 16. And if it might be so in this my present cause, I would safely take my Oath, that what I have said is true. So, they spoke to the Old man my fellow partner, and asked him whether he would take the Oath. So he desired them to give him leave to speake; and he begun to thunder it out against the Bishops, and told them they required three Oathes of the Kings Subjects; namely, the Oath of Churchwardenship, and the Oath of Canonicall Obedience, and the Oath Ex Officio; Which (said he) are all against the Law of the Land, and by which they deceive and perjure thousands of the Kings Subjects in a yeare, And withall, my Lords, (said he) there is a Maxime in Divinity, that we should prefer the glory of God, the good of our King and Country, before our owne lives: but the Lords wondering to heare the Old Man begin to talke after this manner, commanded him to hold his peace, and to answer them, whether he would take the Oath or no? To which he replied, and desired them to let him talke a little, and he would tell them by and by. At which all the Court burst out of a laughing; but they would not let him goe on, but commanded silence, which if they would have let him proceed, he would so have peppered the Bishops, as they were never in their lives in an open Court of Indicature. So they asked us againe, whether we would take the Oath? which we both againe refused; and withall I told them, that for the reasons before I durst not take it. Then they said, they would proceed to Censure. I bid them doe as they pleased, for I knew my selfe innocent of the thing for which I was imprisoned and accused; but yet notwithstanding did submit my body to their Honours pleasure. So they censured us 500 pound a peece; and then stood up Judge Joans, and said: It was fit that I being a young man for example sake, should have some corporall punishment inflicted upon me. So my Censure was to be whipt, but neither time nor place allotted. And for the Old Man, in regard of his age, being 85. yeares old, they would spare his corporall punishment, though (said they) hee deserves it as well as the other (meaning me) yet he should stand upon the Pillory; but I could not understand or perceive by Censure, that I was to stand upon the Pillory. So we tooke our leaves of them. And when I came from the Bar, I spoke in an audible voice, and said: My Lords, I beseech God to blesse your Honours, and to discover and make knowne unto you the wickednesse and cruelty of the Prelates.

So here is an end of my publike proceedings, as yet, which I have had since I came into my troubles, the Lord sanctifie them unto me, and make me the better by them, and put an end to them in his due time, and make way for my deliverance, as I hope he will.

After our Censure we had the libertie of the prison for a few dayes; but the Old Man, my fellow partner, went to the Warden of the Fleete; and told him the summe of that which he intended in the Star-Chamber, to have spoken against the Bishops, if the Lords would have let him; So he told the Warden, how the Bishops were the greatest Tyrants that ever were since Adams Creation; and that they were more crueller than the Cannibals, those Men-eaters, for (said he) they presently devoured men, and put an end to their paine, but the Bishops doe it by degrees, and are many yeares in exercising their cruelty and tyranny upon those that stand out against them; and therefore are worse than the very Canibals; (and in this he saith very true) for the Holy Ghost saith: They that be slaine with the Sword, are better than they that be slaine with Hunger; and he gives the reason of it: For those pine away, striken through, for want of the fruit of the field, Lamen 4. 9. Whereas those that are slaine out-right, are soone out of their paine.) and said he, they have persecuted mee about forty yeares, and cast mee into eight severall Prisons, and all to undoe me, and waste my estate, that so I might not be worth a penny to buy me meate, but starve in prison, for want of food, and yet were never able to lay any thing to my charge, that I had done either against Gods Law, or the Law of the land, and (said he) they are the wickedest men that are in the Kingdome; and I can prove them (saith he) to be enemies of God, and of the Lord Iesus Christ, and of the King and Common-wealth; Or else I will be willing to loose my life; and also told him that they did thrust the Lord Jesus Christ out of his Priestly, Propheticall and Kingly Offices, and hath set up a willworship of their own invention, contrary to the Holy Scriptures; and that they led by their wicked practises the greater halfe of the Kingdome to Hell with them; and that they rob the King of a million of money in a yeare, and the subjects of as much by their powling, sinfull wicked Courts; and that their living by which they lived was got by lying and cozning of poore ignorant Children; for (said he) the Pope and the Priest did promise the Children of deceased Parents, if they would give so much to the Church, they would pray their Parents out of Purgatory, and so cozened them of their estates; & (said he) by such dissemblings and cozening wayes and meanes as this, were their livings at the first raised. Yea, but Sir, (saith the Warden) what is that to them, that was in time of Popery? Yea, but Sir, (said he) their livings hath continued ever since, and they live still to this day upon the sweetnesse and fatnesse of them.

This and much more he then told the Warden, as Mr. Wharton himselfe since then hath told me. And there being a Papist with foure or five more in the roome, the Warden said; Papist come hither, and heare what the Old Man saith. So it came to the Lords of the Counsels eares, whereupon we were the next Munday after brought both together and locked upclose prisoners in one Chamber, without any Order or Warrant at all, but only Warden INGRAMS bare Command and Pleasure; But the Old Man, about three weekes after, made a Petition to the Lords of the Counsell, that he might have some liberty, and being very weake, more likely to dye than to live, hee had his libertie granted till the Tearme; but I doe still remain close Prisoner; but for my own part, I am as cheerefull and merry, and as well contented with my present condition (in regard I see the over-ruling hand of my good God in it) as ever I was with any condition in my life. I blesse his holy name for it, for in all my troubles I have had such sweete and comfortable refreshings from my God, that though my imprisonment, and those straights that I have beene in, might seeme to the World, to be a great and heavy burthen, yet to me it hath beene a happy condition, and a cause of exceeding joy and rejoycing.

From the Fleete, the place of my joy and rejoycing the 12 of March 1637

By me JOHN LILBURNE

Being close Imprisoned by James Ingram the Warden of the Fleete, who locked me up within few dayes after my Sentence, untill the day of my suffering, and would never suffer me to walke in the Prison yard with a Keeper, though I often sent to him, and desired it of him, but told me all was little enough, because I was so refractory.

1.2. ↩

John Liburne, A Light for the Ignorant (1638).↩

A

LIGHT FOR THE IGNORANT

OR

A Treatise shewing, that in the new Testament, is set forth three Kingly States or

Governments, that is, the Civill State, the true Ecclesiasticall State, and the false

Ecclesiasticall State.

Mat. 15. 13.

Every plant which my Heavenly Father hath not planted, shall be rooted up.

Seene and allowed.

Printed in the Yeare, 1638.

The Epistle to the Reader,

VVell affectionated Reader. It is (as thou knowest) a divine precept, that we should giue Honour to whom honour is due: Jmplying therein, that no honour is due either to Persõs or things, but in a lawfull and right way. And hence it is that many of Gods deare Servants both haue and still doe, refuse to yeeld any Reuerence, Honoor, Service, &c. vnto Archbishops Bishops: and their dependent Offices; I say, as they are Ecclesiasticall persons & doe administer in their Spirituall Courts as they terme them: in regard they have assumed such a State as is to speake properly and truely of it, neither Iure Divino nor jure Humano, warrented by the word of God. But of this I shall not need to say any more, in regard thou shalt find what here I say cleared & proved sufficiently: viz. that their calling is not frô God, either in a divine or humane respect, but according to the scripturs after mentioned: altogether & every way from the Devill. And therfore look unto it whosoever thou art, that thou (like Mordecay) bow not the knee to any of these Amalsks, but on the contrarie Feare God and honour the King, and give reverence Only to such ordinances as God binds thy Conscience too, either in respect of nature or grace, and soe doeing thou shalt Give vnto Cæsar the things that are Cæsars, And give vnto God, those things that are Gods. And that thou mayst so doe, the Lord sanctsfie both this and all other good meanes and helps to thee.

A LIGHT FOR THE IGNORANT OR A Treatise shevving, that in the nevv Testament, is set forth three Kingly States or Governments, that is, the Civill State, the true Ecclesiasticall-State, and the false Ecclesiasticall State.

THere are in the new Testement of Christ Iesus three Kinglie States or Governments. The Civill State. The true Ecclesiasticall State. And the false Ecclesiasticall State. Two of them are of God, and the third is of the Divill. They all consist of these Seven particulars following.

In the First, place these three pollitique Regiments hath each of them a King or Head over them.

Secondly, They haue each of them authoritie power or state pollitique.

Thirdly, They haue books and Charters, wherein their statutes, Lawes, and Cannons are writen.

Fourthly, Each of these make themselves Citties Corporations or bodies politique.

Fiftly, They haue Officers and deputies who are their seuerall Ministers to and in there bodies or Corporations.

Sixtly, They have Lawes, ordinances, and administrations for these officers to administer to their subjects, according to there severall functions in the name and by the power of their proper King, and head; from whom they haue received their authority & in whose name they administer.

Sevenlie, and lastlie, they haue subjects or members governed by and in their seuerall pollitique States and powers vnder their severall beads.

The First particular Handled.

These haue each of them a King or Head over them.

The Civill State.

The First is the State of Magistracie or civill State, that wherein Cesar is to haue his due as King and head, these Kings & heads are to be prayed for of all Gods people, as their Heads and gouer nours Rom. 13. 1. 2 1. Tom. 2. 2.

The true Ecclesiasticall State:

This state is Christs the annointed Psa. 2. 6. Acts. 2. 26. whome God the Father hath set upon the Throne of David, Jsay, 9. 6. 7. and he is King of Saints Rev. 15, 3. Yea the King of Kings & Lord of Lords. Rev. 17. 14. & 19, 16.

The False Ecclesiasticall State.

The third is the helish state of the Beast, his Kingdome or state of Rome, which in the 13. Rev. v. 2. is said to haue his power from the Devill; also he is said to haue a Throne: therefore hee is a King 11. c. He is called the King of the Locusts which is there said to bee the Angell of the bottomleste pit. v. 11.

Secondly, these haue each of thẽ a Kingly state or power pollitique

The Civill State.

This power or Civill state is of God, and is the Charracter of Gods soveraigntie over man; is displaid by his Communicating the same unto Kings & such as are in authority under them, for which cause hee hath said yee are Gods; and God must and is obeyed by stooping and submitting to this power and state, and he that resisteth this power resisteth the ordinance of God Rom. 13. c.

The true Ecclesiasticall State.

Likewise this state is of God; for it is the Kingdome of his deare Sonne, & is not the Civill state but the Ecclesiastical state of Christ his Church, or power which he received of his Father Mat 28. 18, after that he rose again from the dead, by which power he authorised his Apostles & sent thẽ on his errand or message to al the world, Mat. 28. which power the Apostles vsed in planting Churchs and Church Officers, which power Christ gives to all the Churches of the Saints to the end of the world, it is the power given to them to bind and loose too, and from the Devill, and to right each others wrongs Mat. 18. it is the same power and state the Churches had comitted to them by the Apostles who reproved the Churches for not using it to suppresse sinne and sinne rs 1 Cor. 5. with the seuen Churches in Asia. Rev. 2. 3. c. these and many more are the severall vsts the Lord hath made of this true Ecclesiasticall or Church state, and Goverment.

The False Ecclesiasticall State.

This Angell of the Bottemlesse pit Rev. 9. 11. the King of the Locusts hath a state, throne, power, and great authority. Rev. 13. 2. & in the same Chapter it is said, he hath power to continue 42 moneths, v. 5. that is 126. dayes as c. 12. 6. counting each day for a yeare (as the Lord doth in numbers, 14. 34. and Ezec. 4. 6,) it is 1260. yeares that is the length or time of his Raigne, that one and the same time which Christs Kingdome vnder the name of the holie City shalbe trod under foot Rev. 11. 2. Likewise that is that power or state that the woman or great whore sits or aids uppon: whereby shee is able to Raigne Rev. 13. 16. & c. 17. as a Queene over the Kings of the earth. And Lastly, this state is soe great that it Captiuates all Kings Princes & Emperours, yea all the world of vngodly men Rev. 13. 7. 8. wonders, followes; and worships this state, or beast, and if they will not he hath such power and authority that hee will compell high and low, rich and poore, bond and free, to submit unto him, & to kill all those that are found refractory to his state and power. Rev. 13. 15. 16. 17. This is the False Ecclesiasticall state and power.

Thirdly, these haue each of them bookes and Chartors to declare their minds to their Subjects.

The Civill State.

Thirdly, all Kings & governours haue Bookes, statutes, and Records, wherein are recorded their Lawes Articles, Acts of Parliament, likewise to Citties and townes Corporated they give Chartors whereby they haue power and preuilidge from their King, & head, in his name and power to instate themselves into divers previledges for their mutuall good.

The true Ecclesiasticall State.

Even soe in the next place Christ Jesus hath given his lawes vnto Iacob & his statutes to Israell, his statute Books are the Holie Scripture of the Old and New Testament, he is faithfull in all his house as was Moses Heb. 3. 2. 6. the acts of his last Parliament which hee called for the establishing of his Kingdome, when hee was 40. daies with his Disciples giving them lawes through the Holy Ghost, even till hee was taken vp into Heaven in their sight, as weemay see in Acts. 1. chapt. Those bookes called the Acts of the Apostles, with-all the Epistles and the Revelation, in these the Cities and Charters of the new Jerusalem is to be found with the previledges thereunto belonging.

The False Ecclesiasticall State.

This smoaky pollitique State of the Crowned Locusts or Roman Clergie Rev. 9. 3. 7. hath distinct bookes from the other two states that are of God, for this State or power hath Bookes of Cannons, Counsels; bookes of Articles, bookes of Ordination of Priests and Deacons; with the booke of Homilies, and the Booke of Common-prayer, and the power and state of this Beast, doth more narrowly looke that all be agreeable to these bookes then the other two states doth (as is manifest by that strict eye that is had ouer all in every parish) not onelie in forraigne Lands, but even in this our Kingdome of England, for they of this Kingdome of Darkenesse are wiser & more diligent in their generatiõ thẽ the children of light.

Fourthly, by vertue of these Charters, these three states make Citties and Corporations, according to their proper & distinct state & power pollitique.

The Civill State.

In the next place the loyall Subjects of this Regiment vnder their King & Head, by vertue of these Charters, become famous Citties, & other inferior corporatiõs agreeable to the tenour of their severall Charters that they received from their Head, & whẽ they received their Charters then & by that means they received the State & power to become a Citty or Corperation vnder that Head, & when they haue vnited or incorporated themselvs into a Bodie they are a Citty constituted, and this state & power they are entered into, is their for me and being, and nothing else doth distinguish them from their former state and condition but that power and state, that is, their state wherein they live moue and haue their being pollitiqucly.

The true Ecclesiasticall State.

In like manner the Subjects of this heavenlie regiment or King dome of Christ, by power from him their Head, doe become visible Churches and bodies incorporated together in his name & power Mat. 18. therefore the Church hee left behind him of 120. were of one accord Acts 1. and to them were vnited or joyned 3000. in the next chapt. so the saints at Antioch, became a body or Church whose constitution or incorporation wee may see to bee a joyning themselves to the Lord Acts. 1. 2. 23. soe all the Churches of the Saints became bodies pollitique, and therefore Gods visible Churches are called Citties or the City of God Psal. 46. 4. Psal. 48. 1. 2. 8. & Psal. 87. 2. 3. Therefore the Saints are called Cittizens Ephes. 2. 19. Inhabitants of the Living God Heb. 12. 22. This holy Cittie is troden under foote 42. Moneths Re. 11. 2. the time of the Raigne of the Beast (Re. 13. 5.) whose Raigne is just so long & this Holy Citty is the new Jerusalem that comes downe from heaven in great glory Rev. 21. the forme or beeing of his divine Citty or spirituall Bodie is the state and power pollitique instituted by Christ and given to his Saints Jude, 3. v. Psal. 133. and thus under Christ as their King they live, moue and haue their being pollitiquelie.

The False Ecclesiasticall State.

So the power of Satan the Devil by hath the wisdome of the second Beast, or false Propher, not only made to himselfe a great Citty whose power killed Christ Rev. 11. 8. Thereby pointing vs 10 the Roman power that still kills his Saints, for this Citty is soe pow e-full that she Raigns over the Kings of the earth, & maks them to drinke of the cup of her fornications, till they be so drunke thereby that they become her servants Rev. 17. 2. 18. & 18. 2. And by this false Ecclesiasticall power & state, there are made lesse Citties called the Citties of the nations of (nation Churches) & are of the same nature Re. 16. 9. as Daughters to the whore & Mother of fornication of the earth, this false great Catholique Church is distributed into nations, provinces, and into every diocesse and parrish, as liuely and apparent as the Civill state, is in every parrish and in every House therein, soe that they live moue and haue their beeing as Royallie from this Beastlike power as the Saints doe by Christ, or subjects under their King, this is plaine by the daily troubles the poore saints suffer in every parrish if they worship not as this power commands.

Fiftly These haue each of them proper and distinct officers belonging to each pollitique State.

The Civill State.

In the first place these Cities by vertue of their Chartors, injoy their owne officers, Majors, Shirrifes, Alderman, and other inferiour Officers as their Lord and King hath allotted them, and also inferiour corporations according as is granted to them in their Chartor, and they that obey these doc well and please God in keeping the first Commandement.

The true Ecclesiasticall State?

Likewise the Citty of God by vertue of their chartor haue right to enjoy their owne Bishops, ouerseeres or Elders Acts, 14. 23. and chap, 20. Titus, 1. 5. 7. Which are not many, yet Wisdome that hath built her house hath found them to be sufficient: which are these, Pastors, Teachers, Elders, Deacons, Widdowes, Rom. 12. 7. 8. Ephe. 4.-11. 12. Phi. 1. 1. 1 Tim. and they that obey these and these onely serve Christ and obey God in keeping the 2. and 3. Commandements, these only being the officers which God by his Holy Apostles hath set up, instituted and placed in his Church to the end of the world: therefore, in Hearing, and obeying these we heare & obey Christ that sent them Luke. 10. 16. Math. 10. 40.

The False Ecclesiasticall State?

In like manner hath this whorith City, or Citties, the False Propher, or Body of false prophets attending upon their forged divises, & humane administrations, which are almost innumirable to reckon frõ the Rope to the parish clark or Paritor whosoever obyes these or any of these breaks the three first Cõmandements, for in hearing & obeying these they hear & obey the Dragon, Beast, & whore, that sent them and gaue them their authority and Office, that as Realie as wee Heare and obey the King by stooping and submitting to a Constable: who sees not this.

These haue each of them proper and severall lawes, statutes, ordinances, and administrations for their severall officers to attend vpon.

The Civill State.

Sixtly, In this state or in these Citties are the lawes and ordinances of men, that the saints must obey in the Lord, for though in the time of Christ and his Apostels there were no Christian Kings, yet the Churches of the Saints were commanded to obey their Lawes, Religious Lawes they could not bee, Because the Magistrates were all infidells, therefore the Apostle Peter distingusheth them from the Divine, by calling them the Ordinances of men, due vnto Caesar as divine obedience is unto God,

The true Ecclesiastcall State.

Even so this Cittie of God with their officers are to obserue what soever Christ hath commanded them Math. 28. 20. the Church of Corinth kept them 1 Cor. 11. 2. and Paulls Charge to Timothy is to teach the Church to obserue all without prefering one before another, as he would answer it before Christ Iesus and his Elect Angells. These divine things are due to Christ Iesus, and to him & to him onely, belongs this visible worship Ioh. 4 21. 22. 23.

The false Ecclesiasticall State.

The Lawes & administrations of this whorish Church, are partly their owne Inventions, contained in the Bookes formerly named, with some divine truthes which vsurped they injoy, which truthes they vse as, a help to set a glose vpon their inventions: that they may passe with a better acceptation but both Divine and devised are consecrated & dedicated by the Beast, and are administred by his Officers and power.

Seauentlhy, All these three haue their subjects or people which their pollitique Bodies consist of.

The Civill State.

Lastly, this State hath Subjects, which are the Kings alleiged people, and are bound to him their Head, by the Oath of alleigence, & as any of them do purchase a Charter from him to become a Cittie or Corporation, they are bound by vertue of their Charters to walkesubmissiuely to him their pollitique head, and in that relation are by duty bound to keepe the Lawes of their Charters in his name & power, which is their pollitique obedience.

This Ciuill State is Gods Ordinance, and is here borrowed to Jllustrate, manifest, and set forth the other two in the former perticuler, and soe we leaue it.

The true Ecclesiasticall State,

Soe in the last place, the Subjects of this State are only Saints & noe other, that is such as by the Rule of the word are to be Judged one of another to be in Christ, otherwise they haue no right to this Kingdome 1 Cor. 4. 20. Chapt. 5. 13. But are intruders lud. 4. verse and soe not of the Kingdome, though in the Kingdome, 1 Iohn 2. 19 and the Saints are out of their places till they come within this Holy Citty.

To this State all Gods people are Called, both out of this world and all false Churches, especially from this Regiment of darkenesse there discribed 2. Cor. 6. 17. & Rev. 18. 4.

The False Ecclesiasticall State,

Lastly, the Subjects of this Kingdome of darkenes are all the Inbabitans of the Earth, Kings & subjects Rev. 13. 16. & Chap. 18. 3. Yea it, hath a commanding power, bond and free, to receive a mark of subjection and servitude, there is none soe bad but will serve his turne, if any proue too good hee casts them out, kills and destroys Rev. 11. 7.

This is the State and Kingdome of darkenes: with which the Devill hath deluded all nations from which all Gods people & Servants are bound in duty to seperate, that soe they may bee free from that wrath of God which shall fall upon the Kingdome of the beast to the Ruine & ouerthrow thereof Rev. 18. 4. 5. & 19. 20. & 14. 9. 10, 11.

Leaving the premises let every one note these ensuing differences or disproportions, that are betwene the z Ecclesiasticall States, for thir different natures.

The true Ecclesiasticall State

The First disproportion betweene the true and False State is, in the Originall from whence they arise. The true State came from Heaven and is the house of wisdomes building Pro. 9. 1. wherin the sonne of God, the wisedome of his Father, Heb. 1. 3. hath beene as faithfull as was Moses in the former Heb. 3. 2. 6. & is that Heaven discribed Rev. 12. 1. and that Citty said to come downe from Heaven Rev. 21, and is an habitation for God to dwell in, and for all his people to come into: to dwell with God their Saviour, for the name of the Citty is, the Lord is there Ezec. last Chap. and last ver.

The False Ecclesiasticall State.

Likewise it is no hard Mistery to know the Originall of this False Ecclesiastical State, for the Clargie, (as Goodwins Catologue of Bishops Fox his Booke of martyrs, & Rev. 9. & 13 ch.) & by their Preaching & writing hath taught vs plainly that Antichrist the man of linne, the sonne of perdition is seated in Rome, & the same Clergy doth also teach us: that their Ministery & Goverments of Bishops & Arch Bb. successiuely proceedes from thence, & for our confirmation here in we read that Gregory the first of that name, Pope of Rome about 1000 yeares since, sent Austin the Monke into Englund & consecrated him first Arch B. of Canterbury, and he consecrated the rest of the Bb. and established the Ecclesiastical state, which state & platforme remaines vn-altered to this day; notwithstanding the Head thereof be changed. This state then being the man of sinne, it is said to arise out of the Bottomles pitt Rev. 9. 1. & is called the King of the Locusts Rev. 9. 11. & is said to come by the effectuall working of Sathan 2 Thess. 2. 9. and as he is the sonne of perdition v. 3. and the Mistery of Iniquity v. 7. so shall he come to confusion by the mouth of the Lord v. 8. & go to perdition Rev. 17. 8. as the sonne & heire thereof, & he shall haue the company of his Fatther the great Dragon the Devill and Satan, with the yonger Brother the False Prophet, that deceiued them that worshipped him, these three shall dwell in the tormenting lake of Gods wrath forever and evermore Rev. 19. 20. & 20. 10. And thus wee see Originally from whence hee came and whither he must goe.

The true Ecclesiasticall State,

A Second disproportion is betweene the true power and the false. The true power which Christ our King hath received of his Father Math. 28. 18. and hath comunicated to his Saints 1 Cor. 5. 4, 12. and Psal. 119. and to them onely; This is that Dominion that the Antient of dayes hath giuen to his Saints Dan. 7. 14. compared with ver. 22. 27: and with Revel. 5. 10. & being lost hee will recover it againe vnto them as Daniel speakes, & in the New Testament is giuen to every Particuler visible Church or Assembly of Saints Math. 18. 17. 19. 20. and 1 Cor. 5. 12. In which point of Power, we are to note two things. Fust the Subject or place where it doth recide, that is in the Body or Assembly of the Saints, as the former scriptures largely declare. Secondly, that they were not forced nor compelled to sabmitt to theis power, but as the loue of God shed abroade in their hearts, & the Doctrine of the Apostles by the power of the spirit caused them freely and willingly to submit them. selves unto it Acts 2. 41. for Christ and his Apostles never used any means to bring his saints into his Kingdome.

The False Ecclesiasticall State.

Soe in Like manner the Dragon that Old Serpent Rev. 12. &illegible; gave to his son of perdition the Beast, his power & throne & great authority Rev. 13. 2. And this man of sinne hath conveyed to all his Cergie his power; by vertue a herof, they are all rulers & men of authority in all nations where he hath established them, as is declared Rev. 9 Chapter & 10 First Verse: swher it is said, hey haue Crowne, upon their heads like gold, that is countersit power and authoritie, & by vertue of this power pollitique; are made one intirebody pollitique, under one head & King soe called vers. 11. and are distinct from the Layety, living in & by the practise of this power, with reference to that Head, though they bee never soe farre disperced or remote from him; this beeing observed, the disproportion will appeare in these two particulers.

First, the subject place where this power doth recide, it beeing in the body of the Clergy, the Layety being excluded though never so high or great in place, as Iudges, Iustices, Lords & Knights &c, they refusing it as a matter not belonging to them, but to the Clergy.

Secondly, this power compells all in all nations, will they nill they to come under this Government, and to obey his power and authority Rev. 13, 8. 16. where it is said, he made all great and small, rich and poore, free and bond, to submit to him, else they should not buy, nor sell nor live ver. 17. and ch. 11. 7.

The true Ecclesiasticall State:

A Third disproportion shall appeare in this, Every Kingdome or pollitique state whether Civill or Ecclesiasticall, hath their severall bookes and Charters: wherein is contayned the Platforme of there severall governments, soe every Church is knowne by its owne articles, Cannons, and Constitutions, so that they that will know what Church, Ministery and worship Christ and his Apostles hath planted in the new Testement after the Ceremoniall was abolished; they must read the Acts of the Apostles with the Epistles Acts, 6. 4. 1. Cor. 14. 37. Revel. 22. 18. 19. Yea the whole new Testement, and there they shall finde Jesus Christ our Lordard King, his Bookes of Cannons, Articles and Ordination, to guide and direct the Churches of the saints in his Kingdome vnto the end of the world.

The False Ecclesiasticall State

Also in the Falle State, they that would know what goverment, Church, Ministery, and worship, the man of sinne hath established, he must viewe his Platforme contayned in his Booke of Cannons, Articles, and Ordintion of the Priests & Deacons, his Bookes of homilies and Common Prayers, for in them is contayned those institutions, Lawes and ordinances that he hath established, but how contrary to the Scriptures of the Old and New Testement; they that are Spirituall in part doe know, and how obedience to them is inforced and divine Lawes omitted and laid aside, the poore saints doe finde, and &illegible; to there smart.

The true Ecclesiasticall State

A Fourth Disproportion. This State makes not Nationall nor Provinciali pollitique Bodies, but only particuler Congregations or assemblies of Saints, as in Judea one Nation; yet divers Churches Gal. 1. 22. Soe Galalia one nation yet many Churches ver. 3. likewise Asia hath seaven seuerall Churches ver. 1. 11. and where there was but one the Holighost speakes in the singuler number, as the Church at Rome, another at Corinth, another at Collossia, another at Thessaloniea, and the like.