Tracts on Liberty by the Levellers and their Critics Vol. 3 (1646)

1st Edition (uncorrected)

Note: This volume has been corrected and is available here </titles/2596>

This volume is part of a set of 7 volumes of Leveller Tracts: Tracts on Liberty by the Levellers and their Critics (1638-1659), 7 vols. Edited by David M. Hart and Ross Kenyon (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2014). </titles/2595>.

It is an uncorrected HTML version which has been put online as a temporary measure until all the corrections have been made to the XML files which can be found [here](/titles/2595). The collection will contain over 250 pamphlets.

- Vol. 1 (1638-1843): 11 titles with 1,562 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-1>

- Vol. 2 (1644-1645): 12 titles with 564 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-2>

- Vol. 3 (1646): 22 titles with 854 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-3>

- Vol. 4 (1647): 18 titles with 2,011 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-4>

- Vol. 5 (1648): 30 titles with 1,078 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-5>

- Vol. 6 (1649): 27 titles with 277 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-6>

- Vol. 7 (1650-1660): 42 titles with 1,055 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-7>

- Addendum Vol. 8 (1638-1646): 33 titles with 1,858 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-8>

- Addendum Vol. 9 (1647-1649): 47 titles with 2,317 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-9>

To date, the following volumes have been corrected:

- Vol. 1 (1638-1643) </titles/2597>

- Vol. 2 (1644-1645) </titles/2598>

- Vol. 3 (1646) </titles/2596>

Further information about the collection can be found here:

- Introduction to the Collection

- Titles listed by Author

- Combined Table of Contents (by volume and year)

- Bibliography

- Groups: The Levellers

- Topic: the English Revolution

2nd Revised Edition

A second revised edition of the collection is planned after the conversion of the texts has been completed. It will include an image of the title page of the original pamphlet, its location, date, and id number in the Thomason Collection catalog, a brief bio of the author, and a brief description of the contents of the pamphlet. Also, the titles from the addendum volumes will be merged into their relevant volumes by date of publication.

Leveller Tracts, Tracts on Liberty by the Levellers and their Critics, Volume 3, 1646

Table of Contents:

- 3.1. [William Walwyn], Tolleration Justified, and Persecution Condemn’d (29 January 1646).

- 3.2. John Lilburne and Richard Overton, The out-cryes of Opressed Commons (February 1646).

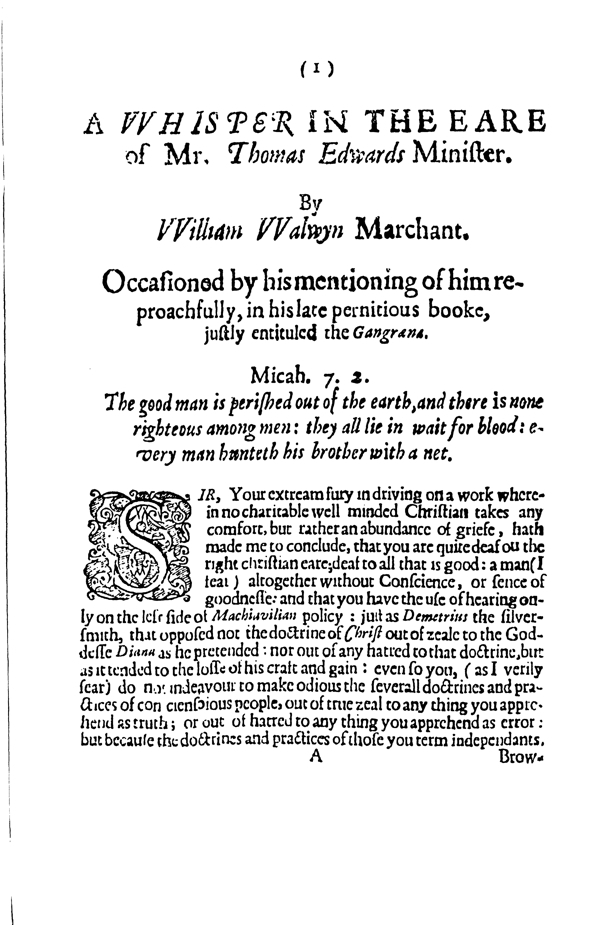

- 3.3. William Walwyn, A Whisper in the Eare of Mr. Thomas Edwards Minister (13 March 1646).

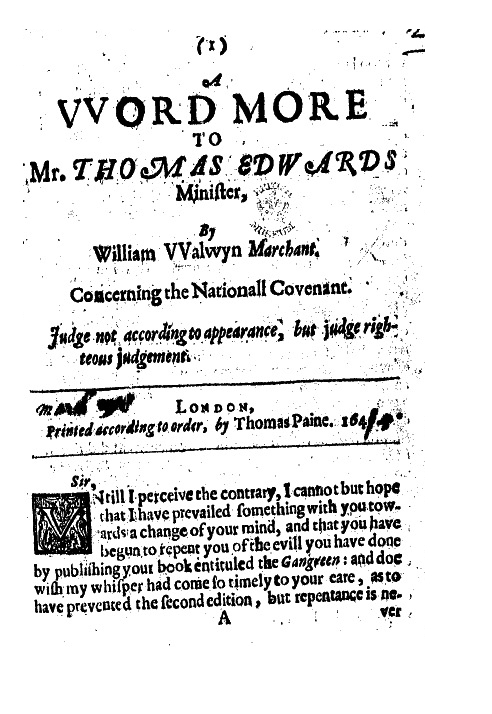

- 3.4. William Walwyn, A Word More to Mr. Thomas Edwards Minister (19 March 1646).

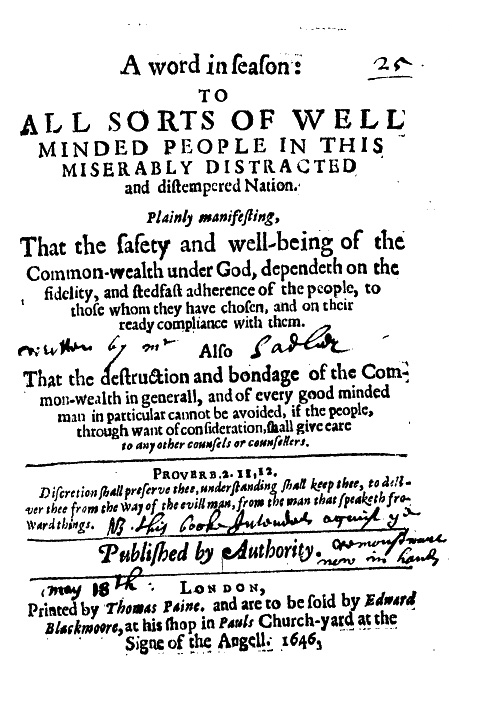

- 3.5. [William Walwyn], A Word in Season: to all sorts of wel minded people in this miserably distracted and distempered nation (18 May 1646).

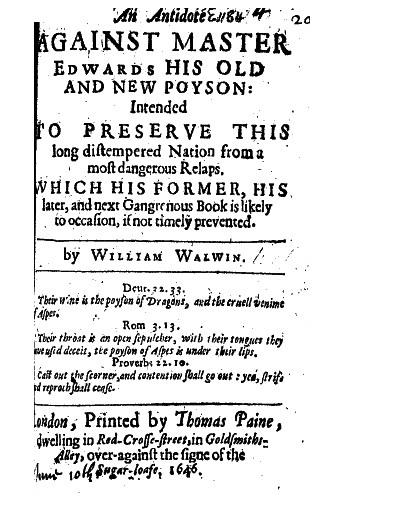

- 3.6. William Walwyn, An Antidote against Master Edwards his old and new Poyson (10 June 1646).

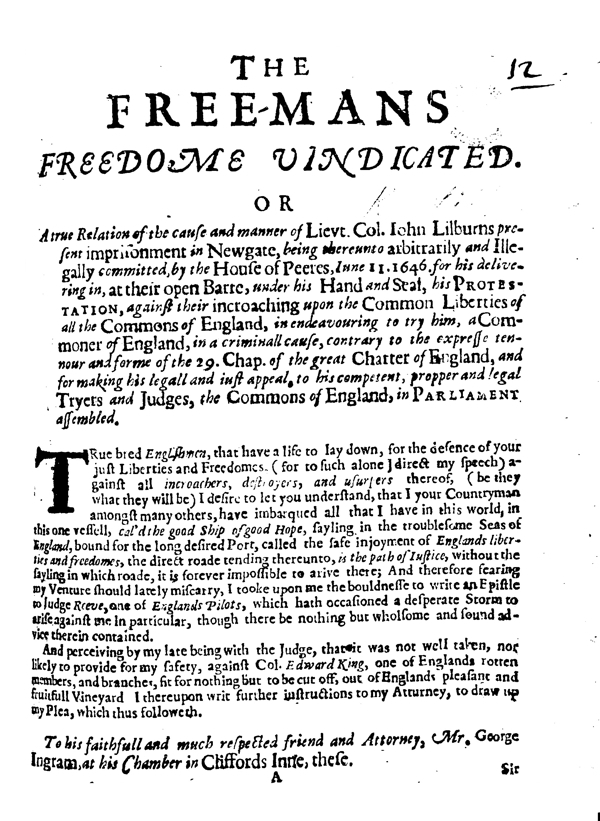

- 3.7. John Lilburne, The Free-mans Freedom Vindicated (16 June 1646).

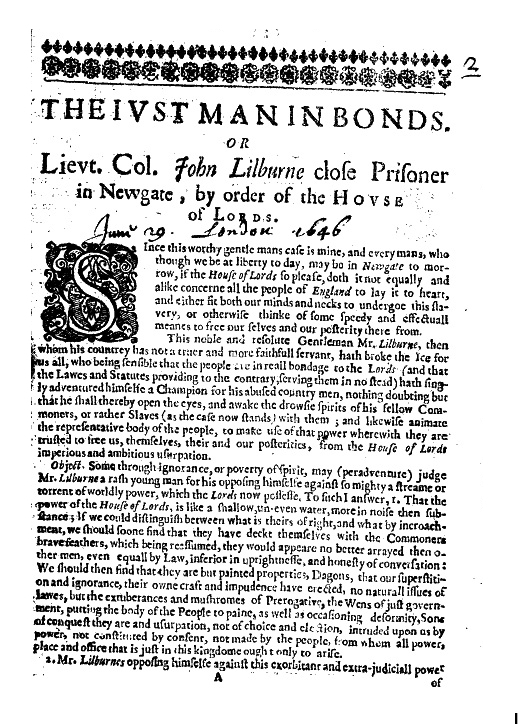

- 3.8. [William Walwyn], The Just Man in Bonds (29 June 1646).

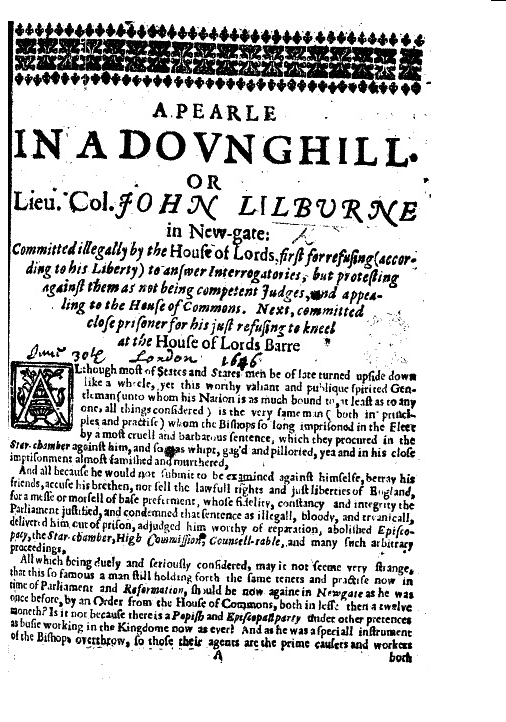

- 3.9. [William Walwyn], A Pearle in a Dounghill (23 June 1646).

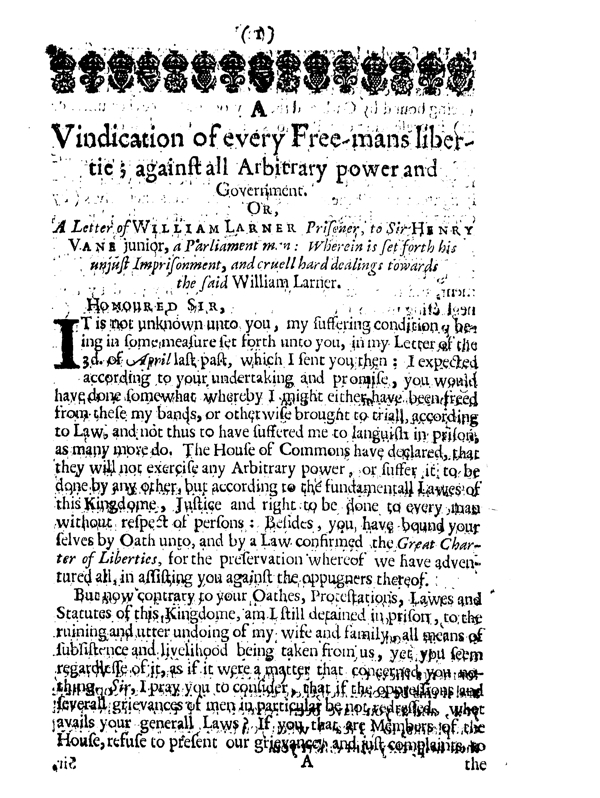

- 3.10. William Larner, A Vindication of every Free-mans libertie against all Arbitrary power and Government (June 1646).

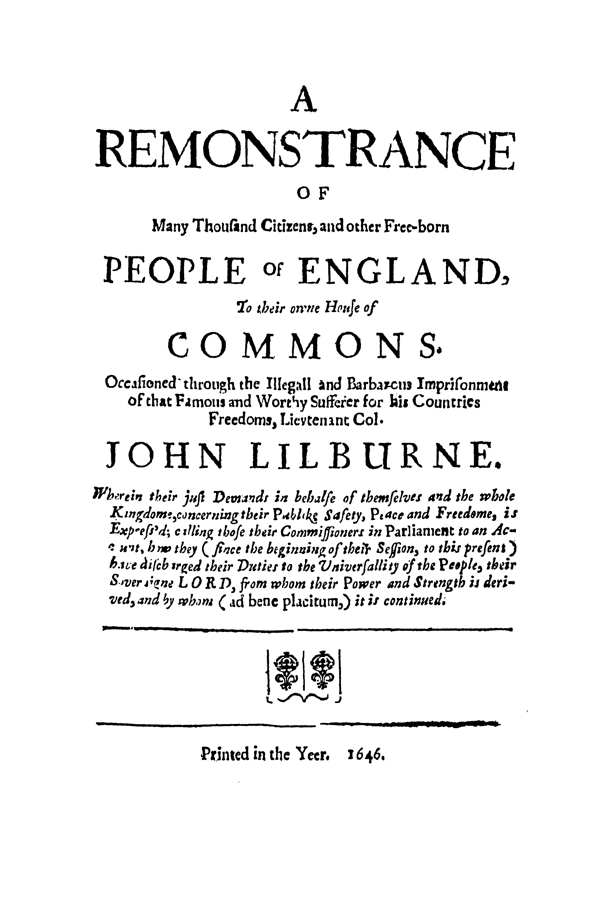

- 3.11. [Richard Overton], A Remonstrance of Many Thousand Citizens, and other Free-born People of England, To their owne House of Commons (17 July 1646).

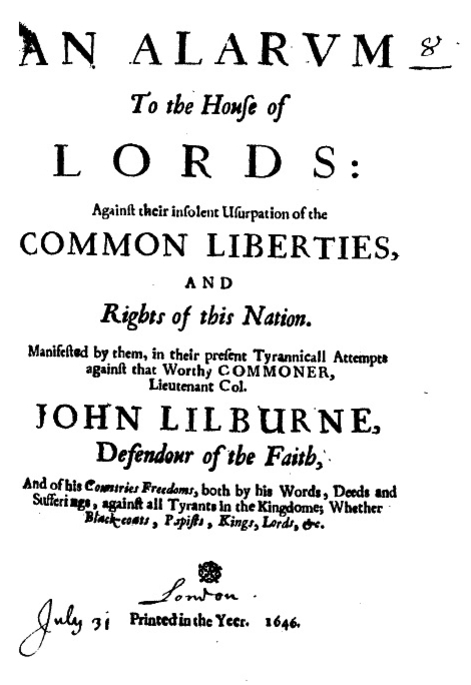

- 3.12. [Richard Overton], An Alarum to the House of Lords: Against their insolent Usurpation of the Common Liberties, and Rights of this Nation(1 August 1646).

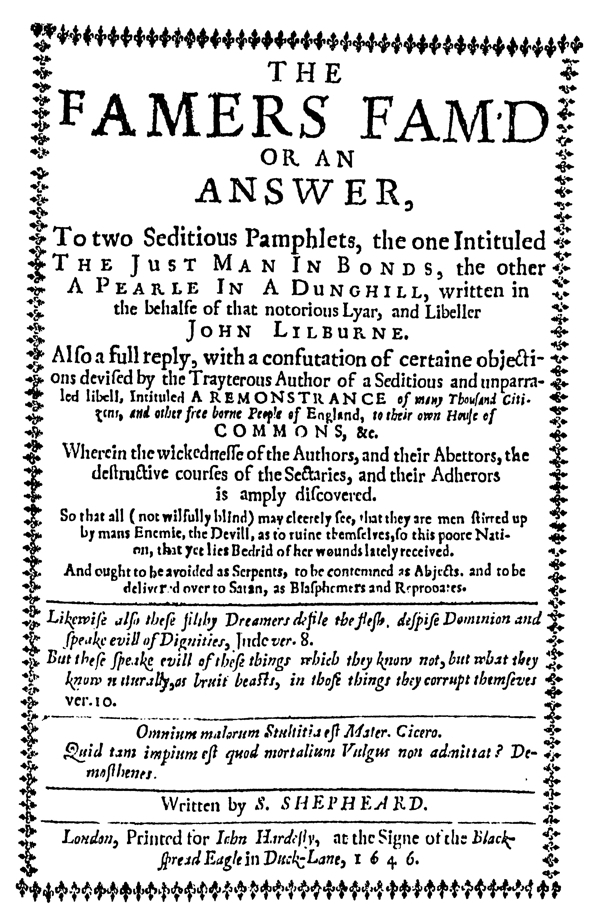

- 3.13. S. Shepheard, The Famers Fam’d or an Answer, To two Seditious Pamphlets (4 August 1646).

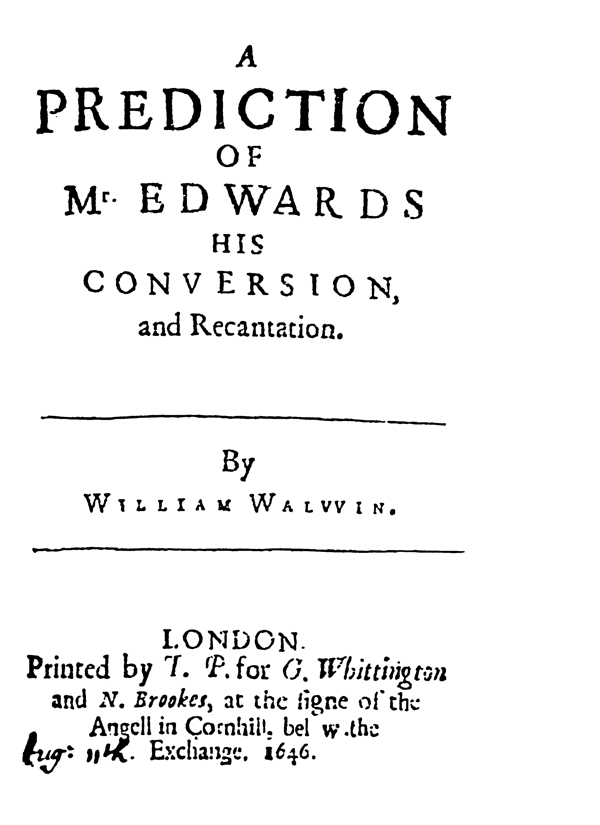

- 3.14. William Walwyn, A Prediction of Mr. Edwards. His Conversion, and Recantation (11 August 1646).

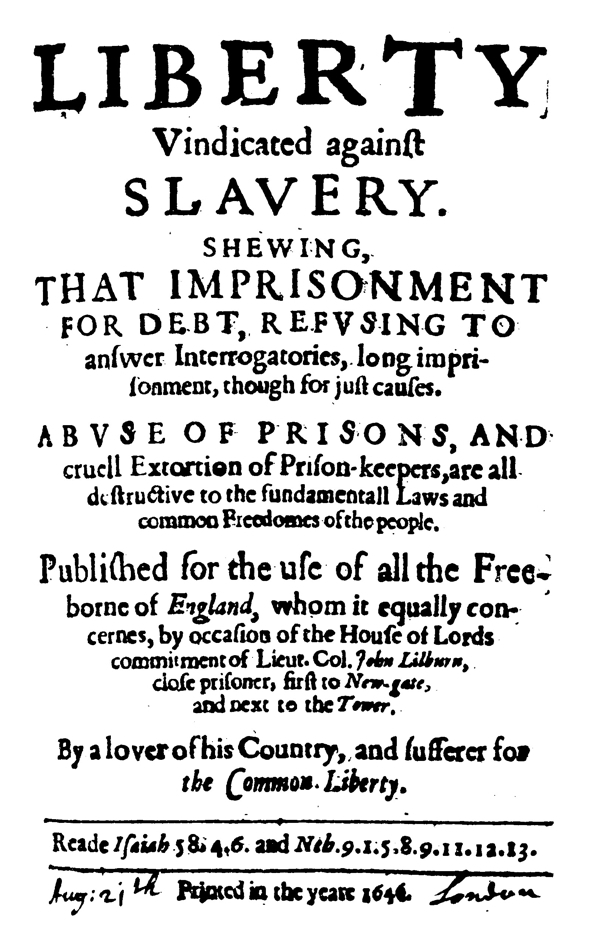

- 3.15. [John Lilburne], Liberty Vindicated against Slavery (21 August 1646).

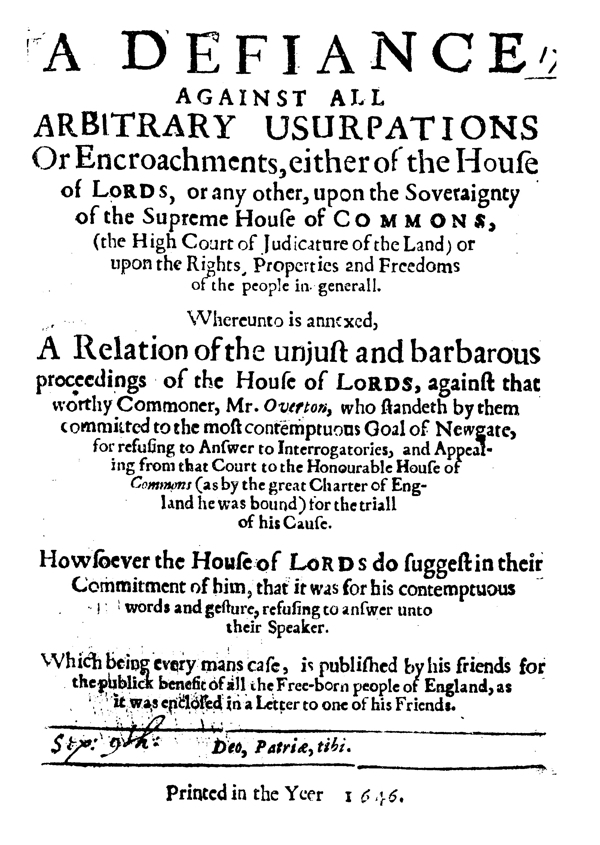

- 3.16. [Richard Overton], A Defiance against all Arbitrary Usurpations Or Encroachments (9 September 1646).

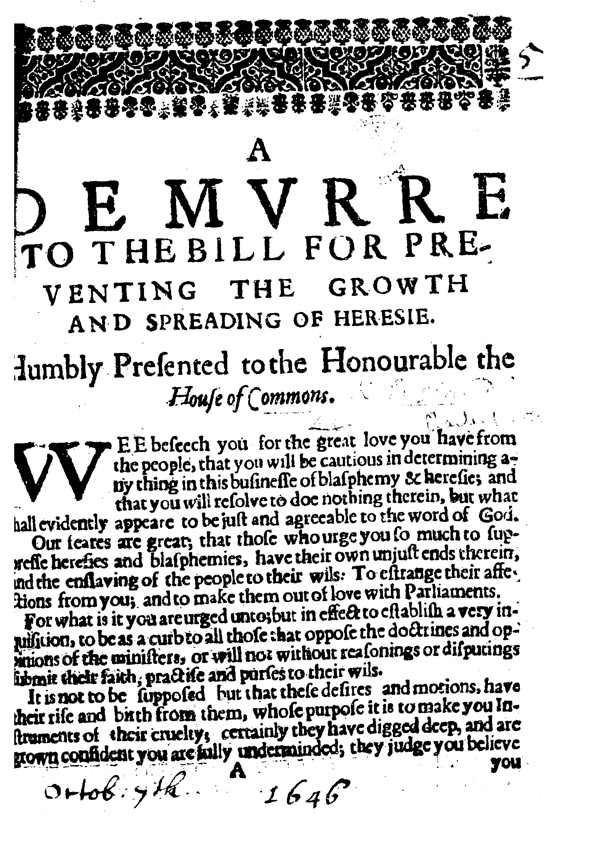

- 3.17. [William Walwyn], A Demurre to the Bill for Preventing the Growth and Spreading of Heresie (7 October 1646).

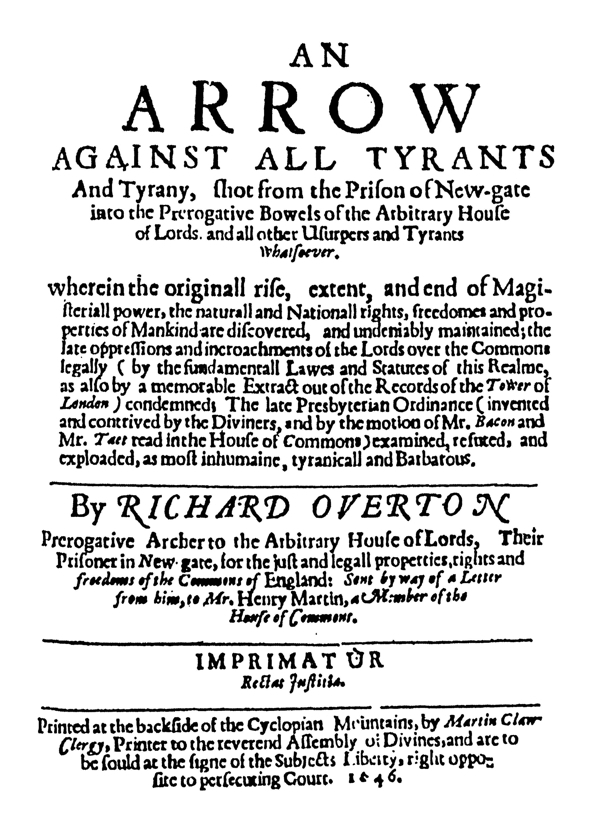

- 3.18. Richard Overton, An Arrow against all Tyrants and Tyranny (12 October 1646).

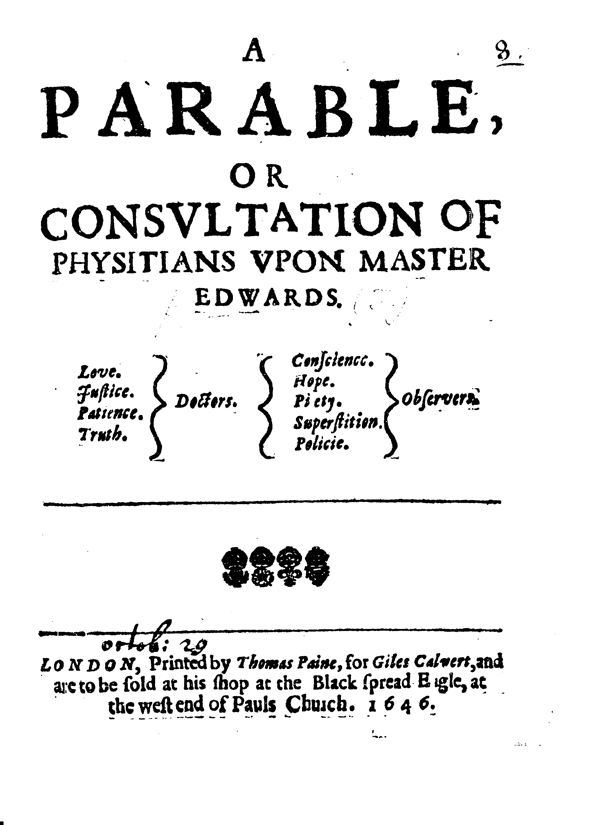

- 3.19. William Walwyn, A Parable, or Consultation of Physitians upon Master Edwards (29 October 1646).

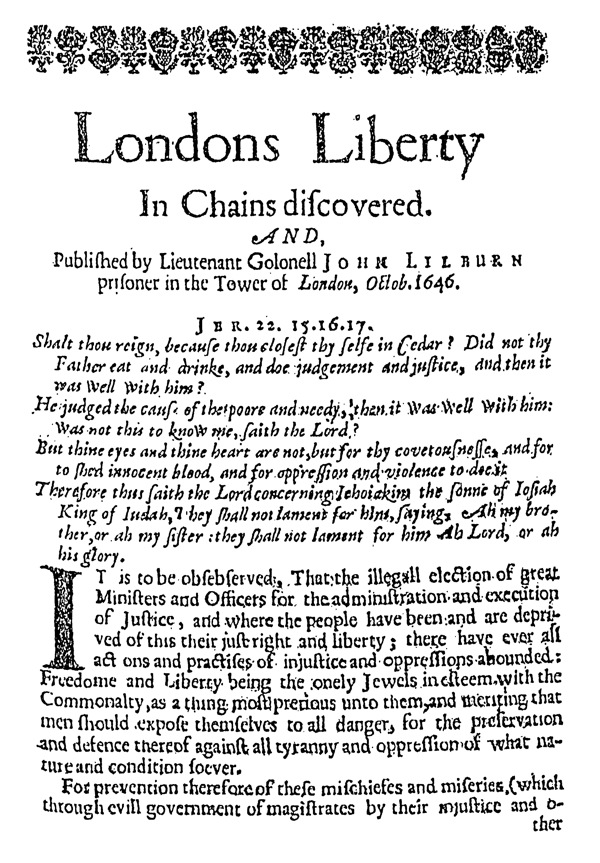

- 3.20. John Lilburne, London’s Liberty in Chains discovered (October 1646).

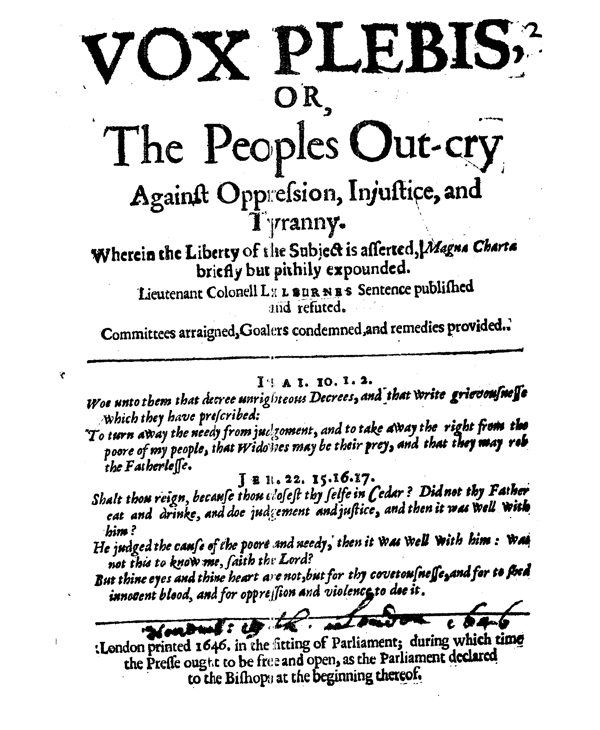

- 3.21. John Lilburne, Vox Plebis, or The Peoples Out-cry Against Oppression, Injustice, and Tyranny (19 November, 1646).

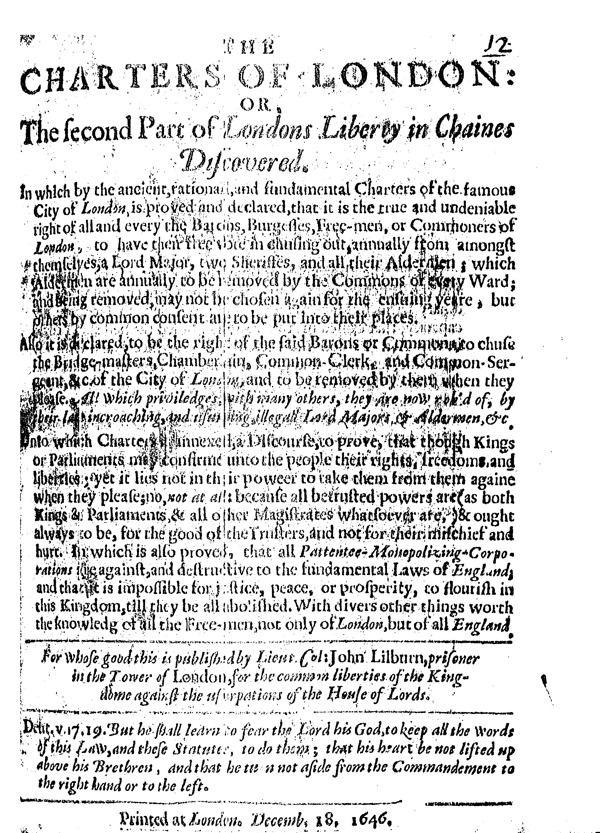

- 3.22. John Lilburne, The Charters of London: or, The second Part of Londons Liberty in Chaines discovered (18 December 1646).

3.1. ↩

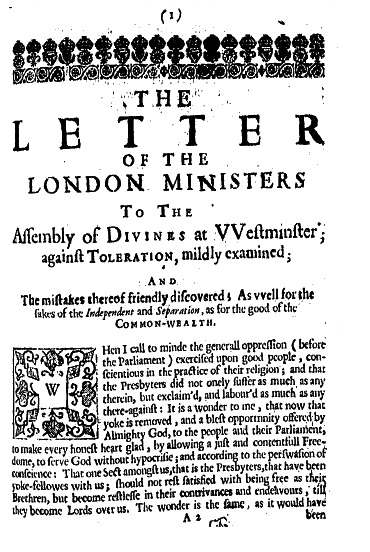

[William Walwyn], Tolleration Justified, and Persecution Condemn’d (29 January 1646).↩

Tolleration Justified,

and Persecution Condemn’d.

In an Answer or Examination, of the London-ministers Letter

Whereof, Many of them are of the Synod, and yet framed this Letter at Sion-Colledge; to be sent among others, to themselves at the Assembly: in behalf of Reformation and Church-government,

2 Corinth. II. vers. 14. 15. And no marvail, for Sathan himself is transformed into an Angell of Light. Therefore it is no great thing, though his Ministers transform themselves, as though they were Ministers of Righteousnesse; whose end shall be according to their works.

London, Printed in the Year, 1646.

THE LETTER OF THE LONDON, MINISTERS TO THE Assembly of DIVINEs af Westminster; against TOLERATION, mildly examined; AND The mistakes thereof friendly discovered; As well for the sakes of the Independent and Separation, as for the good of the COMMON-WEALTH.

When I call to minde the generall oppression (before the Parliament) exercised upon good people, conscientious in the practice of their religion; and that the Presbyters did not onely suffer as much as any therein, but exclaim’d, and labour’d as much as any there-against: It is a wonder to me, that now that yoke is removed, and a blest opportunity offered by Almighty God, to the people and their Parliament, to make every honest heart glad, by allowing a just and contentfull Freedome, to serve God without hypocrisie; and according to the perswasion of conscience: That one Sect amongst us, that is the Presbyters, that have been yoke-fellowes with us; should not rest satisfied with being free as their Brethren, but become restlesse in their contrivances and endeavours, till they become Lords over us. The wonder is the same, as it would have been, had the Israelites, after the Egyptian bondage, become Task-masters in the Land of Canaan one to another, but that is more in them who have been instructed by our Saviour in that blessed rule; of doing unto others, what they would have others doe unto themselves.

To discover the severall policies the Presbiters have used to get into the chayre they have justled the Bishops out of, whose example they have followed in many particulars; as especially in the politick and graduall obtaining the Ordinance for Licencing, upon a pretence of stopping the Kings writings, but intentionably obtained, and violently made use of against the Independents, Separation, and Cornmonwealths-men, who either sees more, or something contrary to the designes of the Licencer. To signifie to the People, how the Presbiters have laboured to twist their interest with the Parliaments, as the Bishops did theirs with the King, how daily and burdensomly importunate they are with the Parliament, to establish their Government, (which they are pleased to call Christs) and back it with authority, and a compulsive power, (which by that very particular appeares not to be his) To lay open their private juncto’s and councels, their framing Petitions for the easie and ignorant people, their urging them upon the Common Councell, and obtruding them upon the chusers of Common Councell men, at the Wardmote Elections, even after the Parliament had signified their dislike thereof; to sum up their bitter invectives in Pulpits, and strange liberty they take as well there, as in their writings, to make the separation and Independents odious by scandals and untrue reports of them, in confidence of having the presse in their own hands, by which meanes, no man without hazard shall answer them, to lay open the manner and depth of these proceedings, is not the intention of this worke; I only thought good to mention these particulars, that the Presbiters may see they walke in a net, no ’tis no cloud that covers them, and that they may fear that in time they may be discern’d as well by the whole People, as they are already by a very great part thereof.

The London Ministers Letter, contriu’d in the conclave of Sion Colledge, is one of the numerous projects of the Clergy: not made for the information of the Sinod, but the misinformation of the People, to prevent which is my businesse at this time; I will only take so much of it as is to the point in hand, to wit, Tolleration.

Letter,

It is true, by reason of different lights, and different sights among Brethren, there may be dissenting in opinion, yet why should there be any separating from Church Communion.

Why? because the difference in opinion is in matters that concerne Church Communion: you may as well put the question, why men play not the Hypocrites? as they must needs do if they should communicate in that Church Society, their minde cannot approve of. The question had been well put, if you had said, by reason of different lights, and different sights, there may be dissenting in opinion, yet why should our hearts be divided one from another? why should our love from hence, and our affections grow cold and dead one towards another? why should we not peaceably, beare one with another, till our sights grow better, and our light increase? These would have been questions I thinke, that would have pusled a truly conscientious man to have found an answer for.

That which next followes, to wit, the Churches coat may be of divers colours, yet why should there be any rent in it: is but an old jing of the Bishops, spoken by them formerly in reference to the Presbiters; and now mentioned, to make that which went before, which has no weight in it selfe, to sound the better.

Letter.

Have we not a Touchstone of truth, the good word of God, and when all things are examined by the word, then that which is best may be held fast; but first they must be knowne, and then examined afterward.

I shall easily concur with them thus farr, that the Word of God is the Touchstone, that all opinions are to be examined by that, and that the best is to be held fast. But now who shall be the examiners, must needs be the question; If the Presbiter examine the Independant and separation, they are like to find the same censure the Presbiters have already found, being examined by the Bishops, and the Bishops found from the Pope: Adversaries certainly are not competent Judges; againe, in matters disputable and controverted, every man must examine for himselfe, and so every man does, or else he must be conscious to himselfe, that he sees with other mens eyes, and has taken up an opinion, not because it consents with his understanding, but for that it is the safest and least troublesome as the world goes, or because such a man is of that opinion whom he reverences, and verily believes would not have been so, had it not been truth. I may be helpt in my examination, by other men, but no man or sort of men, are to examine for me, insomuch that before an opinion can properly be said to be mine, it must concord with my understanding. Now here is the fallacy, and you shall find it in all Papists, Bishops, Presbiters, or whatsoever other sort of men, have or would have in their hands the power of persecuting, that they alwayes suppose themselves to be competent examiners and Judges of other men differing in judgement from them, and upon this weake supposition (by no meanes to be allowed) most of the reasons and arguments of the men forementioned, are supported.

They proceed to charge much upon the Independents, for not producing their modell of Church-government; for answer hereunto, I refer the Reader to the Reasons printed by the Independents, and given into the House in their own justification, which the Ministers might have taken notice of.

I proceed to the supposed Reasons urged by the Ministers, against the Tolleration of Independency in the Church.

Letter.

1. Is, because the Desires and endeavours of Independents for a Toleration, are at this time extreamly unseasonable, and preposterous For,

1. The reformation of Religion is not yet perfected and setled amongst us, according to our Covenant. And why may not the Reformation be raised up at last to such purity and perfection, that truly tender consciences may receive abundant satisfaction for ought that yet appeares.

I would to God the people, their own friends especially, would but take notice of the fallacy of the Reason: They would have reformation perfected according to the Covenant, before the Independents move to be tollerated: now Reformation is not perfected according to the Covenant, till Schisme and Heresie is extirpated; which in the sequel of this Letter, they judge Independency to be, that their charity thinks it then most seasonable, to move that Independency should be tolerated after it is extirpated: their reason and affection in this, are alike sound to the Independants. Their drift in this, indeede is but too evident, they would have the Independents silent, till they get power in their hands, and then let them talke if they dare, certainly, the most seasonable time to move for tolleration is while the Parliament are in debate about Church Government; since if stay bee made till a Church Government bee setled, all motions that may but seeme to derogate from that, how just soever in themselves, how good soever for the Common-wealth, must needs be hardly obtained.

And whereas they say, Why may not Reformation be raised up at last to such purity and perfection, that truly tender consciences may receive abundant satisfaction, for ought that yet appeares.

Observe, 1. That these very Ministers, in the sequel of their Letter, impute it as Levity in the Independents, that they are not at a stay, but in expectation of new lights and reserves, as they say, so that a man would think they themselves were at a certainty: But tis no new thing for one sort of men to object that as a crime against others, which they are guilty of themselves: though indeed but that the Presbiters use any weapons against the Independant’s, is no crime at all, yea ’tis excellency in any man or woman, not to be pertinacious, or obstinate in any opinion, but to have an open eare for reason and argument, against whatsoever he holds, and to imbrace or reject, whatsoever upon further search he finds to be agreeable to, or dissonant from Gods holy Word. It doth appeare from the practises of the Presbiters, and from this Letter and other Petitions expresly against Toleration, that unlesse the Independants and separation will submit their Judgements to theirs, they shall never be tollerated, if they can hinder it.

Their 2. Reason is that it is not yet knowne what the Government of the Independent is, neither would they ever let the world know what they hold in that point, though some of their party have bin too forward to challenge the London Petitioners as led with blind obedience, and pinning their soules upon their Preists sleeve, for desiring an establishment of the Government of Christ, before there was any modell of it extant. Their 3d. Reason, is much to the same purpose.

I answer, 1. That the Ministers know that the Independent Government for the Generall is resolved upon by the Independents, though they have not yet modelized every particular, which is a worke of time, as the framing of the Presbyteria Government was. The Independents however have divers reasons for dissenting from the Presbyterian way, which they have given in already. And though they have not concluded every particular of their owne, but are still upon the search, and enquiry; yet it is seasonable however to move for toleration, for that the ground of moving is not because they are Independents, but because every man ought to be free in the worship and service of God, compulsion being the way to increase, not the number of Converts, but of hypocrites; whereas it is another case for People to move for establishing of a Government they understand not, having never seene it, as the London Petitioners did, that is most evidently a giving up of the understanding to other men, sure the Presbiters themselves cannot thinke it otherwise, nor yet the People upon the least consideration of it. Besides, the London Petitioners did not only desire, as here the Ministers cunningly say, an establishment of the Government of Christ, but an establishment of the Government of Christ (a modell whereof the reverend Assembly of Divines have fram’d, which they never saw) so that herein, the People were abused by the Divines, by being put upon a Petition, wherein they suppose that Government which they never saw, to be Christs Government. If this be not sufficient to discover to our Presbyterian LayBrethren, the Divines confidence of their ability to worke them by the smoothnesse of phrase and Language to what they please, and of their own easinesse, and flexibility to be so led, I know not what is.

2. The Ministers urge that the desires and endeavours of the Independants for Toleration, are unreasonable, and unequall in divers regards.

1. Partly because no such toleration hath heitherto been establisht (sofar as we know) in any Christian State, by the Civill Magistrate.

But that the Ministers have been used to speake what they please for a Reason in their Pulpits without contradiction, they would never sure have let so slight a one as this have past from them: It seems by this reason, that if in any Christian State a Toleration by the Magistrate had been allowed, it would not have been unreasonable for our State to allow it: The practice of States, being here supposed to be the rule of what’s reasonable; whereas I had thought, that the practice of Christian States is to be judg’d by the rule of reason and Gods Word, and not reason by them: That which is just and reasonable, is constant and perpetually so; the practice of States though Christian, is variable we see; different one from another, and changing according to the prevalency of particular partees, and therefore a most uncertain rule of what is reasonable.

Besides, the State of Holland doth tollerate; and therefore the Ministers Argument, even in that part where it seems to be most strong for them, makes against them.

Again, if the practice of a Christian state, be a sufficient Argument of the reasonablenesse of a Tolleration, our State may justly tollerate because Christian, and because they are free to do what ever any other State might formerly have done. But I stay too long upon so weak an Argument.

2. Partly, Because some of them have solemnly protest, that they cannot suffer Presbitary, and answerable hereunto is their practice, in those places where Independency prevailes.

’Tis unreasonable it seems to tollerate Independents, because Independents would not if they had the power, suffer Presbyters. A very Christianly argument, and taken out of the 5. of Matthew 44. Love your Enemies, blesse them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which hurte you, and persecute you: What, were all our London Ministers forgetfull of their Saviours instructions? Does their fury so farre blinde their understanding, and exceed their piety? Which seems to be but pretended now, since in their practice they would become Jews, and cry out an eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth. Whosoever meddles with them it seems, shall have as good as they bring: Was ever so strange a reason urg’d by a Sect of men, that say they are Ministers, Christs Ministers, Reformers too, that would make the world believe they are about to reduce all matters Christian, to the originall and primitive excellency of Christ and the Apostles, and yet to speak and publish to the world a spleenish reason, so expressely contrary to the precepts, to the practice of Christ and his followers. To Christ I say, that bids us love our enemies, that we may be the children of our Father which is in heaven, who makes the Sun to shine on the evill and the good, and sendeth rain on the just and on the unjust. The Ministers should be like the Master, what a disproportion is here? As if the title were taken up for some other end; we know the Apostle speaks of Ministers that could transform themselves as though they were the Ministers of Righteousnesse; I pray God our Ministers do not so, I would willingly suppresse those fears and suspitions; which doe what I can arise in me, from their words and practice. Sure they had approved themselves better christians, if upon the discovery of so bad a spirit in any of the Independents; as to persecute, had they power (though I beleive, there are not any such) I say, it had been more Christ-like in our Ministers, to have disswaded them from so unmanly, so much more unchristianly a vice, then to have it made an argument for practice in themselves. They might by the same rule, be Jewes to the Jew, or Turke to the Turke, Oppressours to the Oppressour; or doe any evill to others, that others would doe to them: if other mens doing of it, be an argument of the reasonablenesse thereof. But I hope, our Ministers will be so ingenious, as when they see their weaknesses forsake them, it will be both more comfortable to all other sorts of men, and in the end more happy for themselves.

2. Again, I suppose your suggestion to be very false; namely, that the Independents if they had power, would persecute the Presbyters: though let me tell you of all sects of men, those deserve least countenance of a State that would be Persecutors, not because of their consciences in the practice and exercise of their Religion, wherein the ground of Freedome consists; but because a persecuting spirit is the greatest enemy to humane society, the dissolver of love and brotherly affection, the cause of envyings, heart-burnings, divisions, yea, and of warres it selfe. Whosoever shall cast an impartiall eye upon times past, and examine the true cause and reason of the subversion, and devastation of States and countries, will I am confident; attribute it to no other, then the Tyranny of Princes, and Persecution of Priests. So that all States, minding their true interests, namely the good and welfare of the people, ought by all meanes to suppresse in every sect or degree of men, whether Papists, Episcopalls, Presbyters, Independents, Anabaptists, &c. the spirit of Domination, and Persecution, the disquieter and disturber of mankind, the offspring of Satan. God being all Love, and having so communicated himselfe unto us, and gave us commands to be like him, mercifull, as he our heavenly Father is mercifull; to bear with one anothers infirmities: neither does reason and true wisdome dictate any other to us, then that we should do unto others, as we would be done unto our selves; that spirit therefore which is contrary to God, to reason, to the well-being of States, as the spirit of Persecution evidently is; is most especially to be watcht, and warily to be circumscribed, and tied up by the wisdome of the supream power in Common-wealths. I speak not this to the disgrace of Presbyters, as Presbyters; for as such, I suppose they are not Persecutors: forasmuch as I know, some, and I hope there are many more of them, that are zealous and conscientious for that form of Government, and yet enemies to a compulsive power in matters of Religion. But for this end only, namely to beget a just and Christian dislike in all sorts of men, as well Presbyters, as others; of forcing all to one way of worship, though disagreeable to their minds: which cannot be done, without the assistance of this fury and pestilent enemy to mankind, Persecution. I proceed to the Ministers third Reason.

3. And partly to grant to them, and not to other Sectaries who are free-born as well as they, and have done as good service as they to the publick (as they use to plead) will be counted injustice, and great partiality; but to grant it to all, will scarce be cleared from impiety.

To the former part of this argument I gladly consent, that Sectaries have as good claimes to Freedome, as any sorts of men whatsoever; because free-born, because well-affected, and very assistant to their country in its necessities. The latter part of the argument is only an affirmation, without proof; the Ministers think sure it will be taken for truth because they said it, for such a presumption it seems they are arrived to. In the mean time what must they suppose the people to be, that do imagine their bare affirmations sufficient ground for the peoples belief; I would the people would learn from hence to be their own men, and make use of their own understandings in the search and beleif of things; let their Ministers be never so seemingly learned or judicious, God hath not given them understandings for nothing; the submission of the mind is the most ignoble slavery; which being in our own powers to keep free, the Subjection thereof argues in us the greater basenesse; but to the Assertion, that it will be impiety to grant it to all Sectaries.

I answer, First, that the word Sectary is communicable both to Presbyters and Independents, whether it be taken in the good sense for the followers of Christ; for such, all Presbyters, Independents, Brownists, Anabaptists, and all else, suppose and professe themselves to be: or in the common sense, for followers of some few men more eminent in their parts and abilities then other. And hereof the Independents and Presbyters are as guilty as the Separation, and so are as well Sectaries. Now all Sectaries, whether Presbyters, Independents, Brownists, Antinomians, Anabaptists, &c. have a like title and right to Freedome, or a Toleration; the title thereof being not any particular of the Opinion, but the Equity of every mans being Free in the State he lives in, and is obedient to, matters of opinion being not properly to be taken into cognisance any farther, then they break out into some disturbance, or disquiet to the State. But you will say, that by such a toleration, blasphemy will be broached, and such strange and horrid opinions, as would make the eares of every godly and Christian man to tingle; what must this also be tolerated? I answer, it cannot be just, to set bounds or limitations to toleration, any further then the safety of the people requires; the more horrid and blasphemous the opinion is, the easier supprest, by reason and argument; because it must necessarily be, that the weaker the arguments, are on one side, the stronger they are on the other: the grosser the errour is, the more advantage hath truth over it; the lesse colour likewise, and pretence there is, for imposing it upon the people. I am confident, that there is much more danger in a small, but speciously formed error, that hath a likenesse and similitude to truth, then in a grosse and palpable untruth.

Besides, can it in reason be judged the meetest way to draw a man out of his error, by imprisonment, bonds, or other punishment? You may as well be angry, and molest a man that has an imperfection or dimnesse in his eyes, and thinke by stripes or bonds to recover his sight: how preposterous would this bee? Your proper and meet way sure is, to apply things pertinent to his cure. And so likewise to a man whose understanding is clouded, whose inward sight is dimn and imperfect, whose mind is so far misinformed as to deny a Deity, or the Scriptures (for we’l instance in the worst of errors) can Bedlam or the Fleet reduce such a one? No certainly, it was ever found by all experience, that such rough courses did confirme the error, not remove it: nothing can doe that but the efficacy and convincing power of sound reason and argument; which, ’tis to be doubted, they are scarce furnisht withall that use other weapons. Hence have I observ’d that the most weak & passionate men, the most unable to defend truth, or their owne opinions, are the most violent for persecution. Whereas those whose minds are establisht, and whose opinions are built upon firm and demonstrable grounds, care not what winds blow, fear not to grapple with any error, because they are confident they can overthrow it.

3. Independency is a Schisme, and therefore not to be tollerated.

The principall argument brought to prove it, is this; Because they depart from the Presbyter Churches, which are true Churches, and so confest to be by the Independents.

I answer, that this Argument only concerns the Independents, because they only acknowledge them to be true Churches. Whether they are still of that opinion or no I know not, ’tis to be doubted they are not, especially since they have discern’d the spirit of enforcement and compulsion to raign in that Church; the truest mark of a false Church. I believe the Independents have chang’d their minde, especially those of them whose Pastors receive their Office and Ministery from the election of the people or congregation, and are not engag’d to allow so much to the Presbyters, because of their own interest; as deriving their calling from the Bishops and Pope, for the making up a supposed succession from the Apostles, who for their own sakes are enforc’d to acknowledge the Presbyter for a true Church, as the Presbyters are necessitated to allow the Episcopall and Papist Church, true or valid for the substance, as they confesse in the ordinance for Ordination, because they have receiv’d their Ministery therefrom, without which absurdity they cannot maintain their succession from the Apostles. But that the Independents are not a schism, they have and will, I believe, upon all occasions sufficiently justifie: I shall not therefore, since it concerns them in particular, insist thereupon; but proceed to the supposed mischiefs which the Ministers say will inevitably follow upon this tolleration, both to the Church and Commonwealth. First, to the Church.

1. Causelesse and unjust revolts, from our Ministery and Congregations.

To this I say, that it argues an abundance of distrust the Ministers have in their own abilities, and the doctrines they preach, to suppose their auditors will forsake them if other men have liberty to speak. ’Tis authority it seems must fill their Churches, and not the truth and efficacy of their doctrines. I judge it for my part a sufficient ground to suspect that for gold that can’t abide a triall. It seems our Ministers doctrines and Religion, are like Dagon of the Philistins, that will fall to pieces at the appearance of the Ark. Truth sure would be more confident, in hope to appear more glorious, being set off by faishood. And therefore I do adjure the Ministers, from that lovelinesse and potency that necessarily must be in Truth and Righteousnesse, if they think they do professe it, that they would procure the opening of every mans mouth, in confidence that truth, in whomsoever she is, will prove victorious; and like the Suns glorious lustre, darken all errors and vain imaginations of mans heart. But I fear the consequence sticks more in the stomacks, the emptying of their Churches being the eclipsing of their reputations, and the diminishing of their profits; if it be otherwise, let it appear by an equall allowing of that to others, which they have labour’d so much for to be allowed to themselves.

2. Our peoples minds will be troubled and in danger to be subverted, Acts 15.24.

A. The place of Scripture may concern themselves, and may as well be urg’d upon them by the Separation or Independents, as it is urg’d by them upon the Separation and Independents; namely, that they trouble the peoples mindes, and lay injunctions upon them, they were never commanded to lay. And ’tis very observable, the most of those Scriptures they urge against the Separation, do most properly belong unto themselves.

3. Bitter heart-burnings among brethren, will be fomented and perpetuated to all posterity.

I answer. Not by, but for want of a Tolleration: Because the State is not equall in its protection, but allows one sort of men to trample upon another; from hence must necessarily arise heart-burnings, which as they have ever been, so they will ever be perpetuated to posterity, unlesse the State wisely prevent them, by taking away the distinction that foments them; namely, (the particular indulgency of one party, and neglect of the other) by a just and equall tolleration. In that family strife and heart-burnings are commonly multiplied, where one son is more cockered and indulg’d then another; the way to foster love and amity, as well in a family, as in a State, being an equall respect from those that are in authority.

4. They say, the Godly, painfull, and orthodox Ministers will bee discouraged and despised.

Answ. Upon how slight foundation is their reputation supported, that fear being despised unlesse Authority forces all to Church to them? Since they have confidence to vouch themselves godly, painfull, and orthodox, me thinks they should not doubt an audience. The Apostles would empty the Churches, and Jewish Synagogues, and by the prevalency of their doctrine convert 3000 at a Sermon; and doe our Ministers feare, that have the opportunity of a Church, and the advantage of speaking an houre together without interruption, that they cannot keep those Auditors they have; but that they shall bee withdrawn from them by men of meaner lights (in their esteeme) by the illiterate and under-valued lay Preachers, that are (as the Ministers suppose) under the cloud of error and false doctrine? Surely they suspect their own Tenetss or their abilities to maintain them, that esteem it a discouragement to bee opposed, and feare they shall be despised if disputed withall.

5. They say, The life and power of godlinesse will be eaten out by frivolous disputes and vain janglings.

Answ. Frivolous disputes and vain janglings, are as unjustifiable in the people as in the Ministery, but milde and gentle Reasonings (which authority are onely to countenance) make much to the finding out of truth, which cloth most advance the life and power of godlinesse. Besides, a Toleration being allowed, and every Sect labouring to make it appear that they are in the truth, whereof a good life, or the power of godlinesse being the best badge or symptome; hence will necessarily follow, a noble contestation in all sorts of men to exceed in godlinesse, to the great improvement of vertue and piety amongst us. From whence it will be concluded too, that that Sect will be supposed to have least truth in them, that are least vertuous, and godlike in their lives and conversations.

6. They urge, That the whole course of religion in private families will be interrupted and undermined.

Answ. As if the Independents and Separation were not as religious in their private families, as the Presbyters.

7. Reciprocall duties between persons of nearest and dearest relations, will be extreamly violated.

Answ. A needlesse fear, grounded upon a supposition, that difference in judgement must needs occasion coldnesse of affection, which indeed proceeds from the different countenance and protection, which States have hitherto afforded to men of different judgements. Hence was it, that in the most persecuting times, when it was almost as bad in the vulgar esteem to be an Anabaptist, as a murtherer, it occasioned dis-inheritings, and many effects of want of affection, in people of nearest relations; but since the common odium and vilification is in great measure taken off, by the wise and just permission of all sects of men by the Parliament, man and wife, father and son, friend and friend, though of different opinions, can agree well together, and love one another; which shews that such difference in affection, is not properly the effect of difference in judgement, but of Persecution, and the distinct respect and different countenance that Authority has formerly shewn towards men not conforming.

8. They say, That the whole work of Reformation, especially in discipline and Government, will be retarded, disturbed, and in danger of being utterly frustrate and void.

It matters not, since they mean in the Presbyterian discipline and Government, accompanied with Persecution: Nay, it will be abundantly happy for the people, and exceedingly conducing to a lasting Peace (to which Persecution is the greatest enemy) if such a government so qualified be never setled. The Presbyters I hope, will fall short in their ayms. i. ’Tis not certain that the Parliament mean to settle the Presbyterian Government, since they have not declared that Government to be agreeable to Gods Word; although the Presbyters are pleasd, in their expressions, frequently to call their Government, Christs Government. Howsoever, their determination (which may well be supposd to be built upon their interest) is not binding: They are call’d to advise withall, not to controul. 2. In case the Parliament should approve of that Government in the main, yet the Prelaticall and persecuting power of it, we may well presume (since they themselves may smart under it as well as the rest of the people) they will never establish.

9. All other Sects and Heresies in the Kingdome, will be encouraged to endeavour the like tolleration.

Sects and Heresies! We must take leave to tell them, that those are termes impos’d ad placitum, and may be retorted with the like confidence upon themselves. How prove they Separation to be Sects and Heresies; because they differ and separate from them? That’s no Argument, unlesse they can first prove themselves to be in the truth? A matter with much presumption supposd, but never yet made good, and yet upon this groundlesse presumption, the whole fabrick of their function, their claim to the Churches, their preheminence in determining matters of Religion, their eager persuit after a power to persecute, is mainly supported. If the Separation are Sects and Heresies, because the Presbyters (supposing themselves to have the countenance of Authority, and some esteem with the people) judge them so: The Presbyters by the same rule were so, because the Bishops once in authority, and in greater countenance with the People, did so judge them to be.

And whereas they say, That Sects and Heresies will be encouraged to endeavour the like tolleration with the Independents.

I answer, that ’tis their right, their due as justly as their cloths, or food; and if they indeavour not for their Liberty, they are in a measure guilty of their owne bondage. How monstrous a matter the Ministers would make it to be, for men to labour to be free from persecution. They thinke they are in the saddle already, but will never I hope have the reines in their hands.

Their 10th. feare is the same.

2. They say the whole Church of England (they meane their whole Church of England) in short time will be swallowed up with distraction and confusion.

These things are but said, not proved: were it not that the Divines blew the coales of dissention, and exasperated one mans spirit against another; I am confidently perswaded we might differ in opinion, and yet love one another very well; as for any distraction or confusion that might intrench upon that civill peace, the Laws might provide against it, which is the earnest desires both of the Independents and Seperation.

2. They say, Tolleration will bring divers mischiefes upon the Commonwealth: For,

1. All these mischeifes in the Church will have their proportionable influence upon the Common-wealth.

This is but a slight supposition, and mentions no evill that is like to befall the Common-wealth.

2. They urge that the Kingdome will be wofully weakned by scandalls and Divisions, so that the Enemies both domesticall and forraigne will be encouraged to plot and practise against it.

I answer, that the contrary hereunto is much more likely, for two Reasons.

1. There is like to be a concurrence, and joynt assistance in the protection of the Common-wealth, which affords a joynt protection and encouragement to the People.

2. There can be no greater argument to the People, to venture their estates and lives in defence of their Country and that government, under which they enjoy not only a liberty, of Estate and Person, but a freedome likewise of serving God according to their consciences, whcih Religious men account the greatest blessing upon earth; I might mention notable instances of late actions of service in Independents and Seperatists, which arising but from hopes of such a freedome, can yet scarce be paraleld by any age or story.

3. They say it is much to be doubted, lest the power of the Magistrate should not only be weakned, but even utterly overthrowne; considering the principles and practices of Independents, together with their compliance with other Sectaries, sufficiently knowne to be antimagistraticall.

An injurious, but common scandal, this whereof much use has been made to the misleading the People into false apprehensions of their brethren the Seperatists, to the great increase of enmity and disaffection amongst us, whereof the Ministers are most especially guilty: Let any impartial man examine the principles, and search into the practises of the separation, and he must needs conclude that they are not the men that trouble England, but those rather that lay it to their charge: the separation indeede and Independents are enemies to Tyranny, none more, and oppression, from whence I beleeve has arisen the fore-mentioned scandall of them: but to just Goverment and Magistracy, none are more subject, and obedient: and therefore the Ministers may do well to lay aside such obloquies, which will otherwise by time and other discovery, turne to their own disgrace.

In the last place they say, ’tis opposite to the Covenant, I. Because opposite to the Reformation of Religion, according to the Word of God, and example of the best Reformed Churches.

I answer, 1, That the example of the best reformed Churches is not binding, further then they agree with the Word of God, so that the Word of God indeed is the only rule. Now the word of God is expresse for tolleration, as appeares by the Parable of the Tares growing with the wheate, by those two expresse and positive rules, 1. Every man should be fully perswaded of the truth of that way wherein he serves the Lord, 2. That whatsoever is not of faith is sinne; and 3. by that rule of reason and pure nature, cited by our blessed Saviour: namely, whatsoever ye would that men should do unto you, that do you unto them.

2. They say it is destructive to the 3. Kingdomes nearest conjunction and uniformity in Religion and Government.

I answer, that the same tolleration may be allowed in the 3. Kingdomes, together with the same Religion and Government; whether it shall be Presbiterian, or Independent, or Anabaptisticall: Besides that I suppose which is principally intended by this part of the Covenant, ’tis the Union of the 3. Kingdomes, and making them each defensive and helpfull to the other, which a tolleration will be a meanes to further, because of the encouragement that every man will have to maintaine his so excellent freedome; which he cannot better do, then by maintaining them all, because of the Independency they will have one upon the other.

3. ’Tis expresly contrary to the extirpation of Schisme, and whatsoever shall be found contrary to sound doctrine, and the power of Godlinesse.

I answer, That when it is certainly determined by judges that cannot err, who are the Schismaticks, there may be some seeming pretence to extirpate them, though then also no power or force is to be used, but lawfull means only, as the wise men have interpreted it; that is, Schisme and Heresie, when they appeare to be such, are to be rooted out by reason and debate, the sword of the Spirit, not of the Flesh; arguments, not blowes: unto which men betake themselves upon distrust of their own foundations, and consciousnesse of their owne inability.

Besides, as the Presbiters judge others to be a Schisme from them, so others judge them to be a Schisme from the Truth, in which sence only the Covenant can be taken.

4. Hereby we shall be involved in the guilt of other mens sinnes, and thereby be endangered to receive of their plagues.

I answer, that compulsion must necessarily occasion both much cruelty and much Hypocrisie: whereof the Divines, labouring so much for the cause, which is persecution, cannot be guiltlesse.

5. It seemes utterly impossible (if such a tolleration should be granted) that the Lord should be one, and his name one, in the 3. Kingdomes.

I suppose they mean by that phrase, it is impossible that our judgements and profession should be one; so I believe it is, whether there be a Tolleration or no. But certainly the likeliest way, if there be any thereunto, is by finding out one truth; which most probably will be by giving liberty to every man to speak his minde, and produce his reasons and arguments; and not by hearing one Sect only: That if it does produce a forc’d unity, it may be more probably in errour, then in truth; the Ministers being not so likely to deal clearly in the search thereof, because of their interests, as the Laity, who live not thereupon, but enquire for truth, for truths sake, and the satisfaction of their own mindes.

And thus I have done with the Argumentive part of the Letter. I shall onely desire, that what I have said may be without prejudice considered: And that the People would look upon all sorts of men and writings, as they are in themselves, and not as they are represented by others, or forestall’d by a deceitfull rumour or opinion.

In this controversie concerning Tolleration, I make no question but the Parliament will judge justly between the two parties; who have both the greatest opportunity and abilities, to discern between the integrity of the one side, and the interest of the other. That the one party pleads for toleration, for the comfort and tranquility of their lives, and the peaceable serving of God according to their consciences, in which they desire no mans disturbance. That the other that plead against it, may (I would I could say onely probably) be swayed by interest and self-respects, their means and preheminence. I make no question but the Parliament, before they proceed to a determination of matters concerning Religion, will as they have heard one party, the Divines, so likewise reserve one ear for all other sorts of men; knowing that they that give sentence, all partees being not heard, though the sentence be just (which then likely will not be) yet they are unjust. Besides, the Parliament themselves are much concerned in this controversie, since upon their dissolution they must mixe with the people, and then either enjoy the sweets of freedome, or suffer under the most irksome yoke of Priestly bondage: and therefore since they are concem’d in a double respect; first, as chosen by the People to provide for their safety and Freedome, whereof Liberty of conscience is the principall branch, and so engag’d by duty: secondly, as Members of the Common-wealth, and so oblig’d to establish Freedome, out of love to themselves and their posterity.

I shall only add one word more concerning this Letter, which is this; That ’tis worth the observation, that the same men are part of the contrivers of it, and part of those to whom ’twas sent; Mr. Walker being President of Sion Colledge, Mr. Seaman one of the Deans, (observe that word) and Mr. Roborough, one of the Assistants, all three Members of the Synod: who with the rest framing it seasonably, and purposely to meet with the Letter from Scotland, concerning Church Government, may well remove the wonder and admiration that seem’d to possesse one of the Scotch grand Divines in the Synod, at the concurrence of Providence in these two Letters: of the politick and confederated ordering whereof, he could not be ignorant.

FINIS.

3.2. ↩

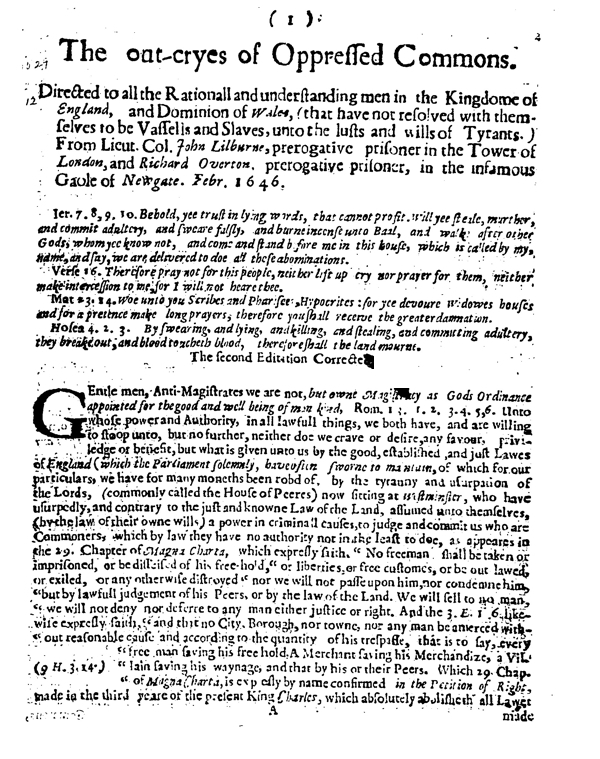

John Lilburne and Richard Overton, The out-cryes of Opressed Commons (February 1646).↩

The out-cryes of Opressed Commons.

Directed to all the rationall and understanding men in the Kingdome of England, and Dominion of Wales, (that have not resolved with themselves to be Vassells and Slaves, unto the lusts and wills of Tyrants.) From Lieut. Col. John Lilburne, prerogative prisone in the Tower of London, and Richard Overton, prerogative prisoner, in the infamous Gaole of Newgate. Feb. 1646.

ler. 7.8, 9.10. Behold, yee trust in lying words, that cannot profit. will yee steale, murther, and commit adultery, and sweare falsly, and burneincense unto Baal, and walk after other Gods, whom yee know not, and come and stand before me in this house, which is called by my name, and say, we are delivered to doe all these abominations.

Verse 16. Therefore pray not for this people, neither lift up cry nor prayer for them, neither make intercession to me, for I will not heare thee.

Mat. 23.14. Woe unter you Scribes and Pharisees, Hypocrites: for yee devoure widowes houses and for a pretence make long prayers, therefore you shall receive the greater damnation.

Hosea 4.2.3. By swearing, and lying, and killing, and stealing, and committing adultery, they breake out, and blood toucheth blood, therefore shall the land mourne.

The Second Edition Corrected.

GEntle men, Anti-Magistrates we are not, but owne Magistracy as Gods Ordinance appointed for the good and well being of men kind, Rom. 13. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5, 6. Unto whose power and Authority, in all lawfull things, we both have, and are willing to stoop unto, but no further, neither doe we crave or desire, any favour, priviledge or benefit, but what is given unto us by the good, established, and just Lawes of England (which the Parliament solemnly, haveoften sworne to maintain, of which for our particulars, we have for many moneths been robd of, by the tyranny and usurpation of the Lords, (commonly called the House of Peeres) now sitting at Westminster, who have usurpedly, and contrary to the just and knowne Law of the Land, assumed unto themselves, (by the law of their owne wills) a power in criminall causes, to judge and commit us who are Commoners, which by law they have no authority not in the least to doe, as appeares in the 29. Chapter of Magna Charta, which expresly saith. “No freeman shall be taken or imprisoned, or be &illegible; of his free-hold,” or liberties, or free customes, or be out lawed, or exiled, or any otherwise distroyed “nor we will not passe upon him, nor condemne him, but by lawfull judgement of his Peers, or by the law of the Land. We will sell to no man, we will not deny nor deferre to any man either justice or right. And the 3. E. 1. 6. likewise expresly saith, “and that no City, Borough, nor towne, nor any man be &illegible; without reasonable cause and according to the quantity of his trespasse, that is to say, every free man saving his free hold. A Merchant saving his Merchandize, a Villain(&illegible; H. 3. 14.) saving his waynage, and that by his or their Peers. Which 29. Chap. of Magna Charta, is expresly by name confirmed in the Petition of Right, made in the third yeare of the present King Charles, which absolutely abolisheth all Lawet made in derogation of the said just Law, which Petition of Right, and every clause there in contained, is expresly confirmed by this present Parliament, as appeares by the statute that abolished the Star Chamber, and the statute, that abolished Ship money. And that learned man of the Law, Sir Edward Cooke, in his exposition of Magna Charta, which booke is published to the publique view of the Kingdome as law, by two speciall orders of the present House of Commons, as in the last pag. thereof you may read, who in his exposition of the 14. chap of Magna Charta, 2. part institutes fol. 28. saith, that by Peers, is meant Equalls, and in fol. 29. he saith, “the generall devision of persons by the law of England is either one that is Noble, and in respect of his Nobility of the Lords House of Parliament, or one of the Commons of the Realm, and in respect thereof, of the House of Commons in Parliament, & as there be divers degrees of Nobility, as Dukes, Marquesses, Earles, Viscounts & Barons and yet all of them are comprehended within this word PARES, so of the Commons of the Realme, there be Knights, Esquires, Gentle-men, Citizens, Yeomen and Burgesses of severall degrees, and yet all of them of the Commons, of the Realme, and as every of the Nobles is one, a PEER to another, though he be of a severall degree, so is it of the Commons, and as it hath been said of men, so doth it hold of noble women, either by birth or by marriage, but see hereof, chap. 29. And in his exposition of chap. 29. pag. Ibem, he saith no man shall be disseised, that is, put out of seison, or dispossessed of his free-hold, (that is) lands or lively hood, or of his liberties, or free customes, that is, of such franchises, and freedomes, and free customes, as belong to him by his free birth-right, unlesse it be by the lawfull judgement, that is, verdict of his EQVALS, (that is, men of his owne condition) or by the law of the land, (that is to speake once for all) by the due course and processe of Law.

No man shall be in any sort destroyed (to destroy i.e.) what was first built and made, wholly to overthrow and pull downe, unlesse it be by the verdict of his EQVALS, or according to the Law of the land. And so saith he is the sentence, (neither will we passe upon him) to be understood, but by the iudgement of his PEERS, that is EQVALS, or according to the Law of the Land, see him, fol. 48. upon this sentence; proindicium parium suorum, and pag. 50. hee saith it was inacted, that the Lords and Peers of this Realme, should not give iudgement upon any but their Peers, and cites Rot. Parl. 4. E. 3. Num. 6. But the Roule is 4. E. 3. Num. 2. in the case of Sir Simon de Bereford, in which the Lords doe ingeniously confesse, that it is contrary to Law, for them to passe iudgement upon a Commoner, being they are not their Peers, that is EQVALS, which record at large you may read in The oppressed mans oppressions declared, Edition the second. pag. 18, 19 And also in part; in Vox plebis, pag. 40. 41.

So that by what hath been said, it cleerly, evidently, and undeniably appeares by the Law of the Land, and the Lords owne confession, that they are not the Peers or Iudges of Commoners in any criminall cases what soever. And we offer (at our utmost perrill) before any legall power in England, to maintain it by the knowne and declared Law of the Land, (which the Lords themselves, have solemnly covinanted and sworne to maintaine) that the Lords by the Law of England, “have not in the least any Iurisdiction at all over any of the Commons of England in any criminall cases whatsoever. But if the studious and industrious Reader, please to read that notable and late printed booke, called Regall tyranny discovered, he shall find that the Author of that book in his 43. 44. 45, 46, 47, and 86. page, layes downe many strong and solid arguments, to prove “that the House of Lords, have not lustly, neither judicative, nor legeslative power at all in them; and in his 94, 95, 96, 97, 98. he declares from very sound and good authority, “that before William the Conquerer and invader, subdued the rights and priviledges of Parliaments, that the King and the Commons held and kept Parliaments, without Temporall Lords, Bishops, or Abbots, the two last of which, viz. Bishops and Abbots he proves, had as true and good right to sit in Parliament, as any of the present Lords now sitting at Westminster, either now have, or ever had, yea, and out of the 20, 21, pages of that notable, and very usefull to be knowne booke, called, The manner of holding Parliaments in England; before and since the conquest, &c. declares plainly, that in times by past, “there was neither Bishop, Earle, nor Baron, and yet even then the King of England kept Parliaments with their Commons only, and though since by INNOVATION, Earles and Barons, have been by the Kings prerogative Charters, (which of what legall or binding authority they are, you may fully read in the Lords and Commons Declaration this present Parliament) summoned to sit in Parliament, yet notwithstanding the King may hold a Parliament, with the Commonalty, or Commons of the Kingdome, without Bishops, Earles and Barons, and saith Mr. William Pryn, in the 1. part of his Soveraign power of Parliaments, pag. 43. (which booke is commanded to be printed by speciall authority, of the present House of Commons) out of Mr Iohn Vowels manner of holding Parliaments, which is recorded in Holingh; Cron. of Ireland, fol. 127, 128. that in times by past the King and the Commons did make a full Parliament, which authority (saith hee) was never hitherto abridged. Yea, this present Parliament in their Declaration concerning the Treaty of Peace in Yorkshire 20. Septem. 1641. betwixt the Lord Fairfax, &c. and Mr. Bellasis, &c. booke decl. 1. part pag 628. doe declare, first that none of the parties to that agreement, had any authority by any act of theirs, to bind that countrey, to any such Nutrality, &illegible; is mentioned in that agreement, it being a peculiar and proper power and priviledge of Parliament, where the whole body of the Kingdome is represented to bind all or any part. And we say the body of the Kingdome, is represented only in the House of Commons, the Lords not being in the least chosen to represent any body at all, yea, and the House of Commons, calls their single order for the receiving of Pole-money, May 6. 1642. 1. part book decl pag. 178. An Order of the House of Parliament, yea, and by severall single orders, have acted in the greatest affaires of the Common-wealth, sometimes against the wills and minds of the Lords, 1. part book decl. pag. 13. 121. 122, 305, 522, 526, 537, 546, 557. book decl. 2. part pag 6, 7, 10, 12. 25. 29. 36. 37. 40, 41. 42. 45. 43, &c. see pag. 877, 878. 879.

And yet notwithstanding all this, the Lords like a company of forsworne men, (for they have often solemnly sworne to maintaine the Law) have by force and violence, indeavoured to their power, and contrary to law, to assume to themselves a judicative power over us, (who are Commons of England in criminall cases) and for refusing to stoop thereunto, have barbarously for many moneths tirannized over us, with imprisonments, &c. And we according to the duty we owe to our native country, and to ourselves and ours, for the preservation of our selves, and the good and just declared lawes and liberties of England, and from keeping our selves and our posterities, from vassalage and bondage, did thereupon according to law and justice, appeale to the honourable House of Commons (as you may truly and largely read in divers and sundry bookes, published by us, and our friends) as the supreame and legall power and judicature in England, whom we did thinke and judge, had been chosen of purpose, by the free men of England to maintaine the fundamentall good lawes and liberties thereof, but to their everlasting shame (and the amazement of all that chose and betrusted them.) We are forced to speake it, we have not found any reall intentions in them, to performe unto us, the trust in that Particular reposed in them by the whole Kingdome, neither, have we any grounded cause to say (in truth) any otherwise of them, but that they are more studious and industrious unjustly in deviding hundred thousands of pounds of the Common wealths money amongst themselves, then in actuall doing to us (in whom all and every the Commons of England are concerned, for what by the wills of the Lords, is done to us to day, may be done to any Commoner of England to morrow) either justice or right, according to their duty, and their often sworne oathes, though we have not ceased continuall to the utmost of our power, legally, and iustly to crave it at their hands, as you may fully read in our forementioned printed bookes. Sure we are; they tell us in their printed Declarations, that they are chosen and betrusted by the people, 1. part bok. decl. pag, 171, 172. 263. 264, 266, 336, 340. 361, 459. 462-508 588, 613, 628. 690, 703, 705, 711 714. 716. 724, 725. 729. And that to provide for their weale, but not for their woe, book decl. 1. part page 150: 81 382. 726. 728.

And they in their notable Declaration of the 2. Novemb. 1642. booke decl. 1 part pag. 700, expresly tell us, that all interests of publique trust is only for the publique good, and not for private advantages, nor to the prejudice of any mans particular interest, much lesse of the publique, and in the same page they further say, that all interests of trust, is limitted to such ends or uses, and may not be imployed to any other, especially they that have any interests only to the use of others, (as they confesse all Interests of trust are) cannot imploy them to their owne, or any other use, then that for which they are intrusted, yea, and page 266. they tell the King, that the whole Kingdome it selfe is intrusted unto him for the good and safety and best advantage thereof, and as this trust is for the use of the Kingdome, so ought it to be managed by the advice of the Houses of Parliament, whom the Kingdome hath intrusted for that purpose, it being their duty to see it be &illegible; according to the condition, and true intent thereof, and as much as in them lyes, by all possible meanes to prevent the contrary. And in page 687. being answering a charge that the King laid upon them, which was, as they cite it, that we can doe him no wrong, because he is not capable of receiving any, and that we have taken nothing from him, because he never had any thing of his owne to lose, upon which they demand the question, and say, in what part of that Declaration (meaning theirs of the 26. May, 1642.) is this told the King in plain English, or by any good inference? unlesse it must needs follow, that be “cause the King hath not a right of property in the Townes, Forts, Subjects, publique treasure and offices of the Kingdome, nor in the Kingdome it selfe to dispose of it at his pleasure, and for his owne private advantage, but only a trust for the commnn good of himselfe and his Subjects* (as it is most cleare he hath them no otherwise) that therefore he cannot have a proper. &illegible; in any of the Lands or goods, as Subiects have in theirs, and yet it is a truth that the more publique any person is, the more interest the publique hath even in those things that belong to him as a private man, in which regard the King hath not the like liberty, in disposing of his owne person, or of the persons of his children (in respect of the interest the Kingdome hath in them) as a private man may have.

And therefore negatively in the second place, we are sure, that the House of Commons, by their owne Declarations, were never intentionally chosen and sent to Westminster to devide amongst themselves, the great offices and places of the Kingdome, and under pretence of them to make themselves rich and mighty men, with sucking and deviding among themselves, the vitall and heart blood of the Common wealth, (viz. its treasure) now lying not in a swound, but even a gasping for life and being, but let us see whether this and other of their late doings, be according to their former protestations, imprecations and just Declarations, which if they be not woe to them, for saith the spirit of God, Eccle. 5. 4. 5. When thou vowest a vow unto God defer not to pay it; for he hath no pleasure in fooles, pay that which thou hast vowed. For better it is that thou shouldest not vow, then that thou shouldest vow and not pay, see Deut. 23. 21. 23. That which is gone out of thy lyps, saith God, thou shalt keep and performe, Num. 30. 2. Psal. 76. 21. Iob 22. 27 Eze. 17. 16, 17, 18, 19, Eze. 5. 4. 5. We find in their Declaration of the 5. May 1642. book de. 1. par p. 172 these words, The Lords and Commons therefore &illegible; with the safety of the Kingdome, and peace of the people (which they call God to witnesse is their only aime) finding themselves denyed these their so necessary and iust demands (about the Militia) and that they can never be discharged before God or man, if they should suffer the safety of the Kingdome, and peace of the people, to be exposed to the malice of the Malignant party, &c. And in there Remonst. of the 19. of May, 1642. &illegible; del. 1 par. p. 195. they say, That the providing for the publique peace, and the prosperity of all his Maiesties Realmes: within the presence of the all seeing diety, we protest to have been, and still to be the only end of all our counsells and indeavours, wherein we have resolved to continue freed and inlarged from all private aimes, personall respects or passions whatsoever. But we wish withall our soules, they had intended, what they here declared, when they declared it, which is too much evident to every rational mans eyes, that sees and knowes their practises, that they did not, or that if they did, that they have broken and falcified their words and promises, and in the same Remonst. p. 214. speaking of those many difficulties they meet with in the discharge of their places, and duty, they say, “Yet wee doubt not, but we shall overcome all this at last, if the people suffer not themselves to be deluded, with false and specious shewes, and so drawn to betray us to their owne undoing we have ever been willing to hazzard the undoing of our selves, that they might not be betrayed by our neglect of the trust reposed in us, but if it were possible, they should prevaile herein, yet we would not faile through Gods grace still to persist in our duties, and to looke beyond our owne lives, estates and advantages, as those who thinke nothing worth the enjoying, without the liberty, peace and safety of the Kingdome: nor any thing too good to be hazzarded in discharge of our consciences, for the obtaining of it, and shall alwayes repose our selves upon the protection of almighty God, which we are confident shall never be wanting to us, (while wee seek his glory) as we have found it hitherto, wonderfully going along with us, in all our proceedings. O golden words! unto the makers of which we desire to rehearse the 23. Mat. 27, Woe unto you Scribes, and Pharisees, Hypocrites, for yee are like unto whited Sepulchers, which indeed appeare beautifull outward, but are within full of dead mens bones, and of all uncleannesse. And in their Remon. May. 26. 1642. p. 281. They declare, “that their indeavours for the preservation of the Lawes and liberties of England, have been most hearty and sincere, in which indeavour, say they, by the grace of God we will still persist though we should perish in the worke; which if it should be, it is much to be feared, that Religion, Lawes, liberties and Parliaments, will not be long lived after us: but saith Christ, Mat. 23. 23, 28. Woe unto you Scribes and Pharisees, Hypocrites for yee make cleane the outside of the cup, and of the platter, but within they are full of extortion and excesse. Yee also appeare outwardly righteous unto men, but within yee are full of hypocrisie and iniquity. And in their Decla. of July, 1642. concerning the distractions of the Kingdome, &c p. 463. 464. speaking of the businesse of Hull, they say, “the war being thus by his Maiesty begun, the Lords and Commons in Parliament, hold themselves bound in conscience to raise forces for the preservation of themselves, the peace of the Kingdome and protection of the Subiects in their persons and estates, according to Law, the defence and securite of Parliament, and of all those who have been imployed by them in any publique service for these ends, and through Gods blessing, to disappoint the designes, and expectations, of those who have drawn his Maiestie to these courses and Counsells, in favour of the Papists at home, the Rebells in Ireland, the forraign enemies, of our Religion and peace.

“In the opposing of all which, they desire the concurrence of the well disposed Subjects of this Kingdome, and shall manifest by their courses and indeavours, that they are carried by no respects but of the publique good, which they will alwayes prefer before their owne lives and fortunes. O that we might not too justly say! they are already falne from their words.

And in their most notable Declaration of August, 1642. pag. 498. being in great distresse they cry out in these words, “and we doe here require all those that have any sence of piety, honour or compassion, to helpe a distressed state, especially such as have taken the Protestation, and are bound in the same duty with us unto their God, their King and country, to come in to our aid and assistance, this being the true cause, for which we have raised an Army, under the command of the Earle of Essex, with whom in this quarrell wee will live and dye.

And in their answer to his Majesties message of the 12 of No. 1642. p. 750. they have these words, God who sees our innocency, and that we have no aimes, but at his glory and the publique good, &c. O golden language, but without reall performance, are but an execrable abomination in the sight of God, and all rationall men.

But when these Declarations and Promises were solemnly made, the Authors of them tooke it extreame ill at the hands of the King, when he told them they dissembled, and meerly sought themselves, and their owne honour and greatnesse, which he doth to the purpose in severall of his Declarations, but especially in his Declaration of the 12. August, 1642. pag. where speaking of the earnest desire he had to ease and satisfie his Subjects, he saith, that whilst we were busie in providing for the publique, they were contriving particular advantages of offices and places for themselves, and made use underhand of the former grievances of the Subiect, in things concerning Religion and Law, &c. and in the next pag. speaking of their zeale against the Bishops, &c. He declares their designe, was but of their goodly revenue to erect Stipends to their owne Clergy, and to raise estates to repaire their owne broken fortunes.*

And in the Same Remonstrance pag. 539. he declares, that after many feares and iealousies were begun, they would suffer no meanes to compose it, but inflamed the people, because (he saith) they knew they should not only be disappointed of the places, offices, honours, and imployments they had promised themselves, but be exposed to the justice of the law, and the just hatred of all good men.

All which they in their antient and primitive declarations disdaine, as most dishonourable to be fixed upon them, or supposed ever intentively to be acted by them, especially so visibly that any should be able to see it, and therefore in their 3. Remonstrance, book decl. 1. part pag. 264. “they labour to perswade the people not to destroy themselves, by taking their lives, liberties, and estates out of their hands, whom they have chosen and betrusted therewith, and resigne them up to some evill Counsellours about his Majestie, who (they say) are the men that would perswade the people, that both Houses of Parliament containing all the Peers, and representing all the Commons of England, would destroy the Laws of the land, and liberties of the People, wherein besides the trust of the whole, they themselves in their owne particular, have so great an interest of honour and estate, that we hope it will gaine little credit with any, that have the least use of reason, that such as have so great ashire in the misery, should take so much paines in the procuring thsreof, and spend so much time, and run so many hazzards to make themselves slaves, and to destroy the property of their estates. But we say in the bitternesse of our soules. O! that their actions and dealings with us, and many other free men of England, had not given too just and grounded cause to judge that the foremntioned charge of the King, was righteous, just, and true upon them, and which if their owne consciences were not seared with hot Irons, and so past feeling, would tell them with horror* that he spoake the truth.

And in the forementioned most notable Declaration, pag. 494. one of the principall things they complaine of against the King, and his evill Counsellers is, ‘that they endeavour to possesse the people that the Parliament will take away the law, and introduce an arbitrary Government; a thing (say they) which every honest morall man abhors, much more the wisedome; justice, and piety of the two Houses of Parliament,* and in truth such a charge as no rationall man can beleeve it, it being unpossible so many severall persous, as the Houses of Parliament consists of about 600. and in either House of equall power shall all of them, or atleast the Major part, agree in acts of will and tyranny, which make up an arbitrary government,* and most improbable, that the nobillity and chiefe gentry of this Kingdome, should conspire to take away the Law, by which they injoy their estates, are protected from any act of violence, and power; and differenced from the meaner sort of people, with whom otherwise they should be but fellow servants.

And when they come to answer the Kings maine charge, laid to them, in his Declaration, in answer to theirs of the 26. of May, 1642. they say, book decl. pag. 694. “As for that concerning our inclination to be slaves, it is affirmed, that his Majesty said nothing which might imply any such inclination in us, but sure, what ever be our inclination, slavery would be our condition, if we should goe about to overthrow the Lawes of the Land,* and the propriety of every mans estate, and the liberty of his person. For therein we must needs be as much patients as agents, and must every one in his turne suffer our selves, whatsoever we should impose upon others, we have refused to doe or suffer our selves, and that in a high proportion. But there is a strong and vehement presumption, that we affect to be tyrants, and what is that? because we will admit no rule to governe by but our owne wills:* But we wish the charge might not too truly be laid upon you. For our parts, we aver, wee feele the insupportable weight of it upon both our shoulders.

And therefore to conclude this, we desire to informe you, that in severall of their Declarations, they declare and professe, they “will maintaine what they have sworne in their protestations, the which if you please to read, you shall find there amongst other things, that they have sworne solemnly to maintaine the lawfull rights and liberties of the Subject, and every person whatsoever, that shall lawfuly in deavour the preservation thereof and therefore book dec. 2. part pag. 497. they solemnly imprecate the judgements of God to fall upon them, if they performe not their vowes,* promises and duties; and say woe to us if we doe it not, at least doe our utmost indeavours in it, for the discharge of our duties, and the saving of our soules, and leave the successe to God Almighty*.

Now what the liberty of the Subject is, they themselves in their Declarations excellent well discribe and declare; “that it is the liberty of every Subject to injoy the benefit of the law, and not arbitrarily and illegally to be committed to prison, but only by due course and &illegible; of law, nor to have their lives, liberties nor estates taken from them, but by due course and processe of Law, according to Magna Charta and the Petition of Right which condemnes as unjust all Interrogatorie proceedings in a mans owne case, nor to be denyed Habeas Corpusses, nor baile in all cases whatsoever, that by law are baileable, and to injoy speedy tryalls without having the just course of the law, obstructed against them, 1. part book decl. pag. 6, 72, 38, 77. 201. 277. 278. 458, 459. 660, 845.

Yea, in their great Declaration of the 2. Novemb. 1642. book. decl. 1. part. pag. 720 they declare “it is the liberty and priviledge of the people, to Petition unto them for the ease and redresse of their grievances, and oppressions, and that they are bound in duty to receive their Petitions, their own words are these, “we acknowledge that we have received Petitions, for the removall of things established by law, and we must say, and all that know what belongeth to the course and practice of Parliament, will say that we ought so to doe, and that our predicessors and his Majesties Ancestors have constantly done it there being no other place wherein lawes, that by experience may be found grievous and burthensome can be altered or repealed, and there being no other due and legall way, wherein they which are agrieved by them, can seeke redresse; yea, in other of their Declarations, they declare, that is, the liberty of the people in multitudes to come to the Parliament to deliver their Petitions, and there day by day to waite for answers to them, &illegible; part book. decl page 1. 2 3. 201. 202. 209. 548.