Tracts on Liberty by the Levellers and their Critics Vol. 4 (1647)

1st Edition, uncorrected (Date added: March 18, 2015)

This volume is part of a set of 7 volumes of Leveller Tracts: Tracts on Liberty by the Levellers and their Critics (1638-1659), 7 vols. Edited by David M. Hart and Ross Kenyon (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2014). </titles/2595>.

It is an uncorrected HTML version which has been put online as a temporary measure until all the corrections have been made to the XML files which can be found [here](/titles/2595). The collection will contain over 250 pamphlets.

- Vol. 1 (1638-1843): 11 titles with 1,562 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-1>

- Vol. 2 (1644-1645): 12 titles with 564 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-2>

- Vol. 3 (1646): 22 titles with 854 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-3>

- Vol. 4 (1647): 18 titles with 2,011 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-4>

- Vol. 5 (1648): 30 titles with 1,078 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-5>

- Vol. 6 (1649): 27 titles with 277 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-6>

- Vol. 7 (1650-1660): 42 titles with 1,055 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-7>

- Addendum Vol. 8 (1638-1646): 33 titles with 1,858 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-8>

- Addendum Vol. 9 (1647-1649): 47 titles with 2,317 illegible words and characters. </pages/leveller-tracts-9>

To date, the following volumes have been corrected:

- Vol. 1 (1638-1643) </titles/2597>

- Vol. 2 (1644-1645) </titles/2598>

- Vol. 3 (1646) </titles/2596>

Further information about the collection can be found here:

- Introduction to the Collection

- Titles listed by Author

- Combined Table of Contents (by volume and year)

- Bibliography

- Groups: The Levellers

- Topic: the English Revolution

2nd Revised Edition

A second revised edition of the collection is planned after the conversion of the texts has been completed. It will include an image of the title page of the original pamphlet, its location, date, and id number in the Thomason Collection catalog, a brief bio of the author, and a brief description of the contents of the pamphlet. Also, the titles from the addendum volumes will be merged into their relevant volumes by date of publication.

Tracts on Liberty by the Levellers and their Critics, Volume 4 (1647) (1st edition, uncorrected)

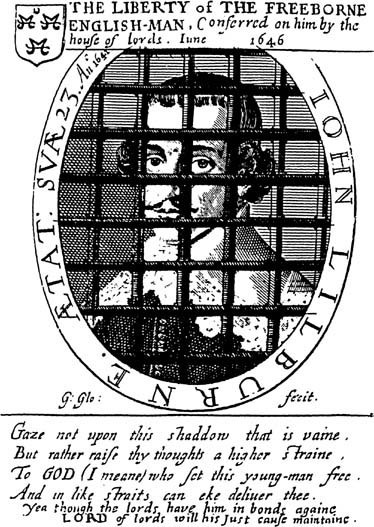

The Liberty of the Freeborne English-Man, Conferred on him by the house of lords. June 1646. John Lilburne. His age 23. Year 1641. Made by G. Glo.

“Gaze not upon this shaddow that is vaine,

Bur rather raise thy thoughts a higher straine,

To GOD (I meane) who set this young-man free,

And in like straits can eke thee.

Yea though the lords have him in bonds againe

LORD of lords will his just cause maintaine.”

Table of Contents

- Editor’s Introduction to Volume 4 (1647)

- Publishing and Biographical Information

- Copyright and Fair Use Statement

- Tracts from 1647 (Volume 4) (2,011 illegibles)

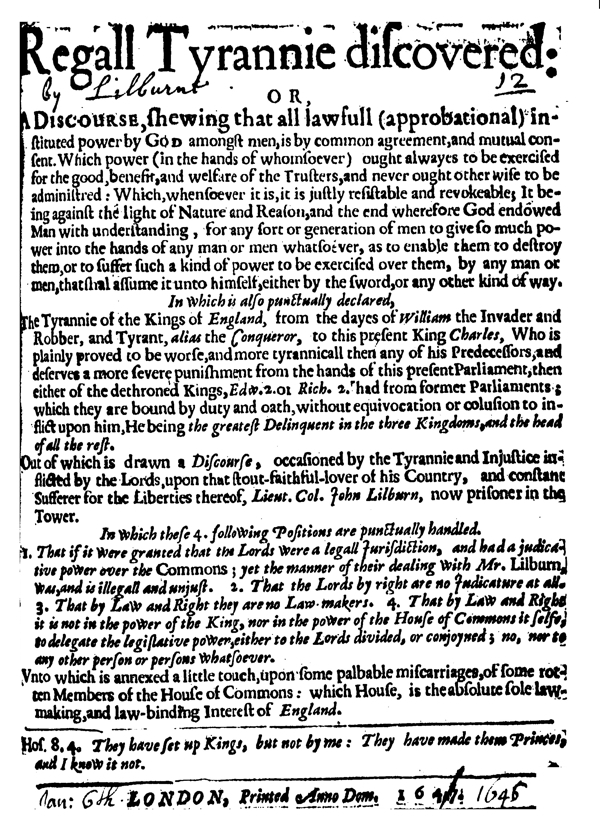

- 4.1. John Lilburne, Regall Tyrannie discovered: Or, A Discourse, shewing that all lawfull (approbational) instituted power by God amongst men, is by common agreement, and mutual consent. (6 January 1647) [305 illegibles]

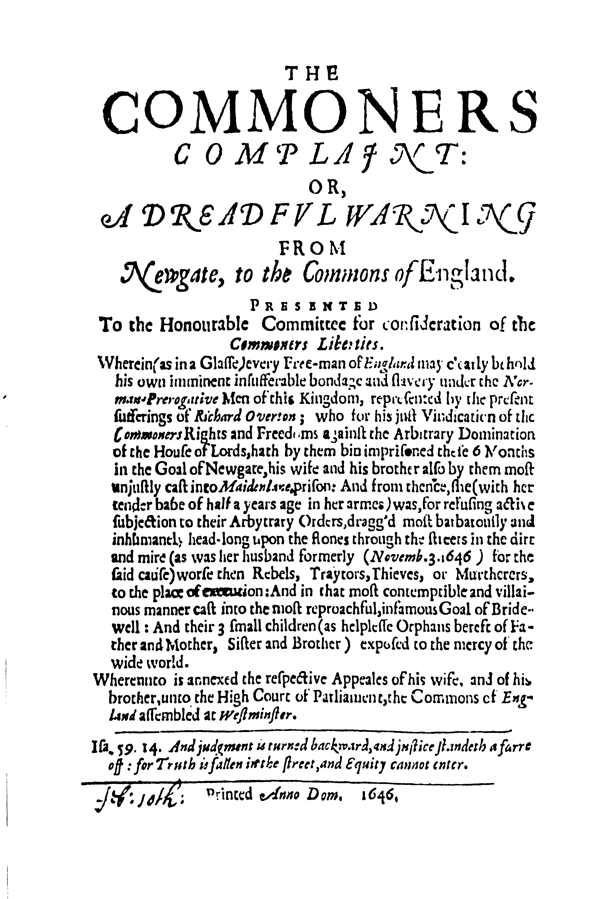

- 4.2. [Richard Overton], The Commoners Complaint: Or, A Dreadful Warning from Newgate, to the Commons of England. (10 February 1647). [7 illegibles]

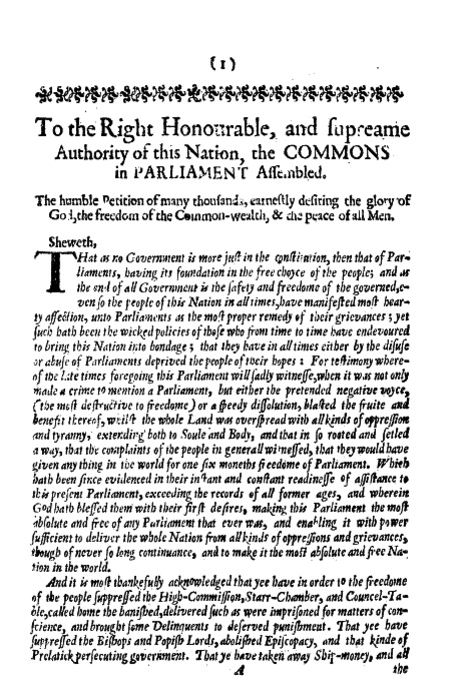

- 4.3. [Several Hands but probably a major role by William Walwyn], [also known as “The Petition of March”], To the Right Honourable and Supreme Authority of this Nation, the Commons in Parliament assembled. (March 1647)

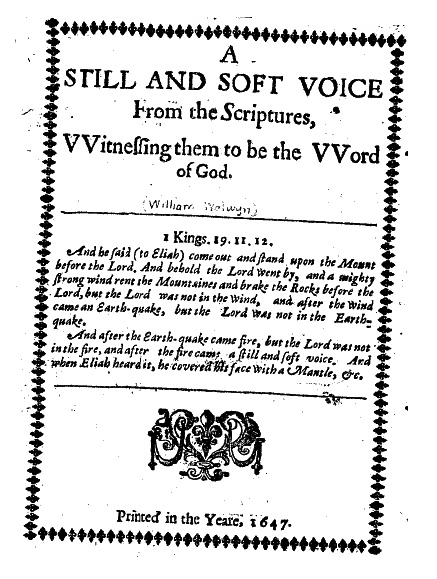

- 4.4. William Walwyn, A Still and Soft Voice From the Scriptures Witnessing them to be the Word of God. (March/April 1647).

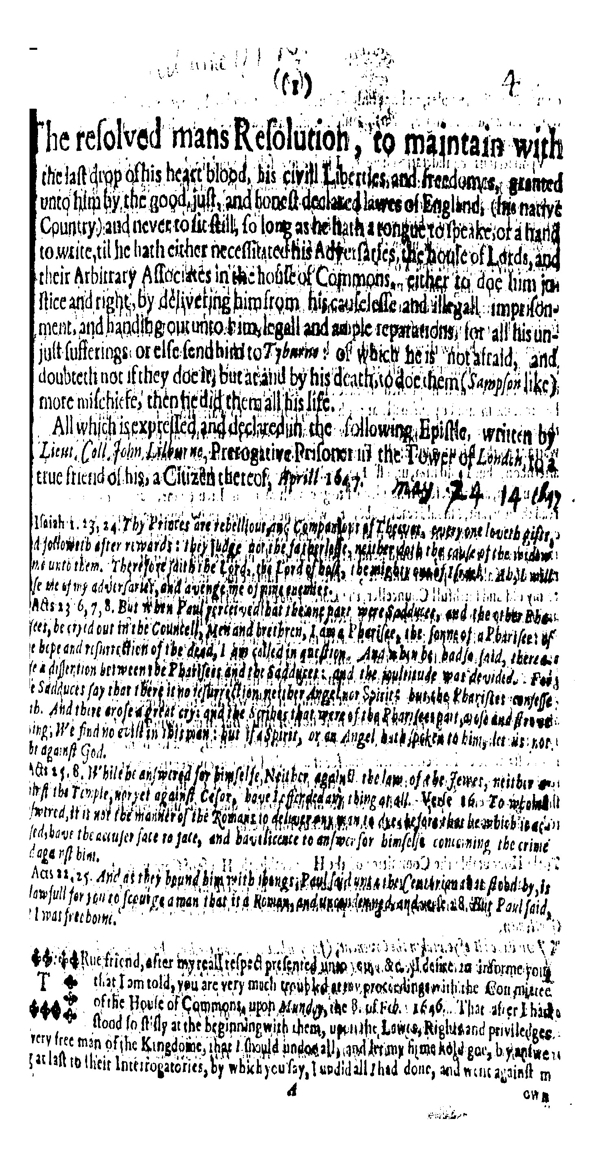

- 4.5. John Lilburne, The resolved mans Resolution, to maintain with the last drop of his heart blood, his civill Liberties and freedomes (30 April 1647). [1,436 illegibles]

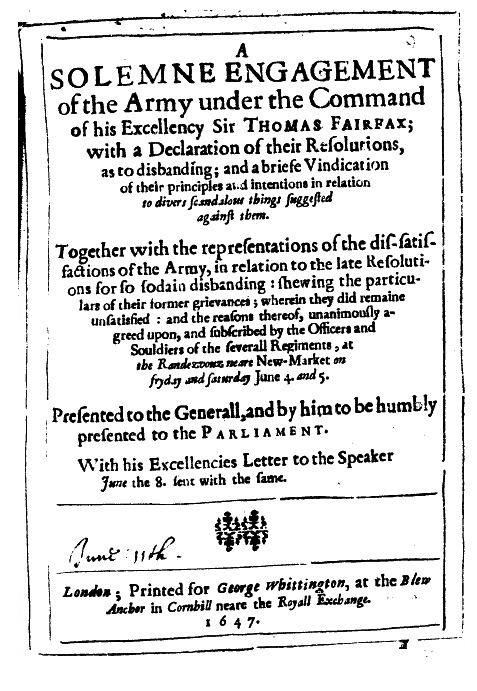

- 4.6. Anon., A Solemne Engagement of the Army (5 June 1647)

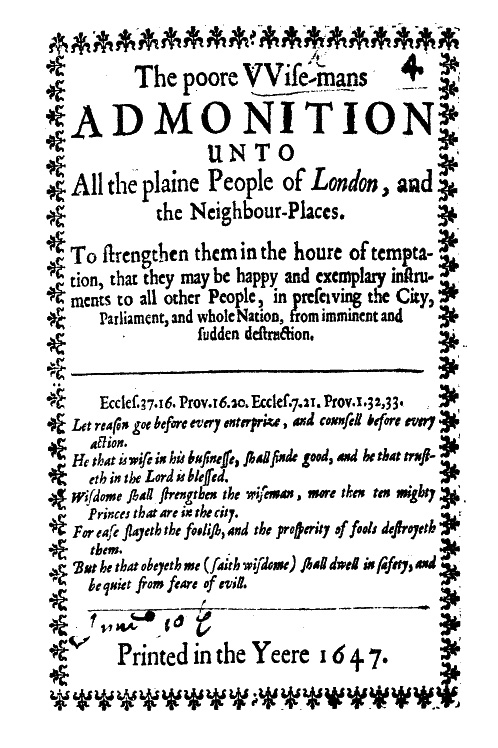

- 4.7. [William Walwyn], The poore Wise-mans Admonition unto All the plaine People of London, and Neighbour-Places. (10 June 1647).

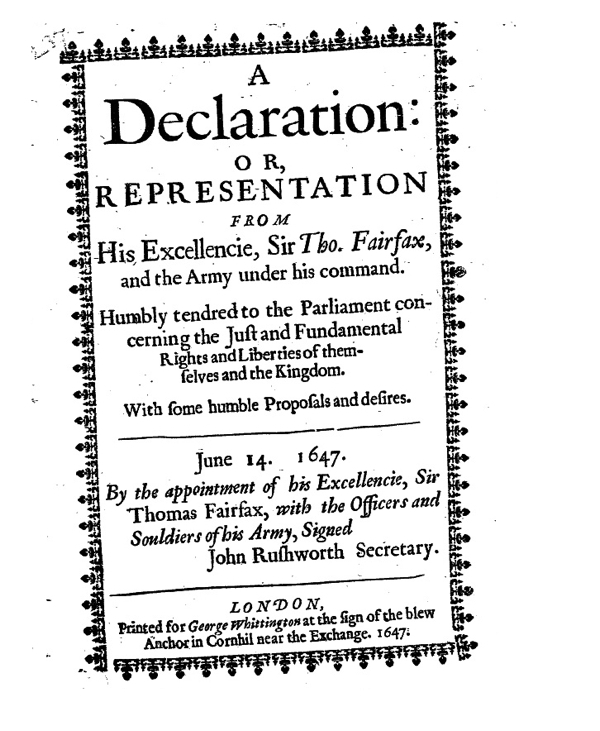

- 4.8. [Signed by John Rushworth, attributed to Henry Ireton], [Declaration of the Army], A Declaration, or, Representation From his Excellency, Sir Thomas Fairfax, And the Army under his command, Humbly tendred to the parliament (14 June 1647).

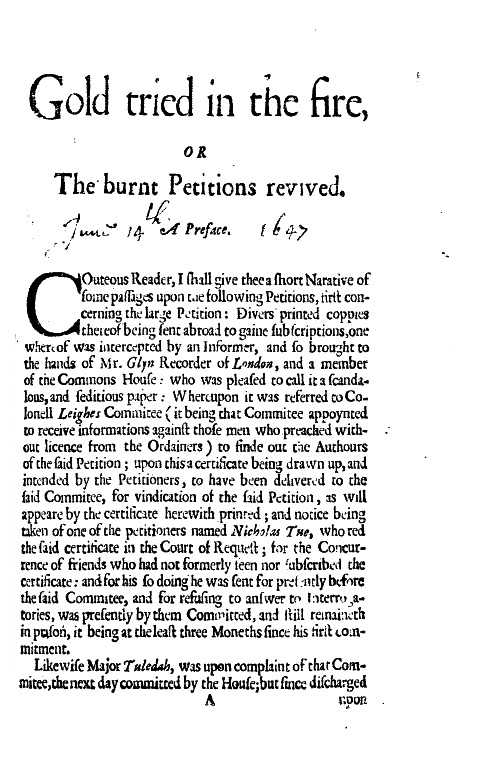

- 4.9. [William Walwyn], Gold Tried in the Fire, or The burnt Petitions revived. (14 June 1647).

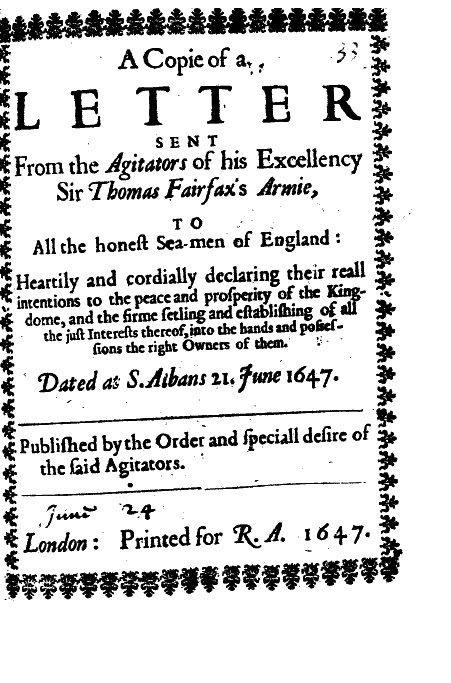

- 4.10. [Several hands, calling themselves “Agitators”], A Copie of a Letter Sent From the Agitators of his Excellency Sir Thomas Fairfax’s Armie, To All the honest Sea-men of England. (21 June 1647).

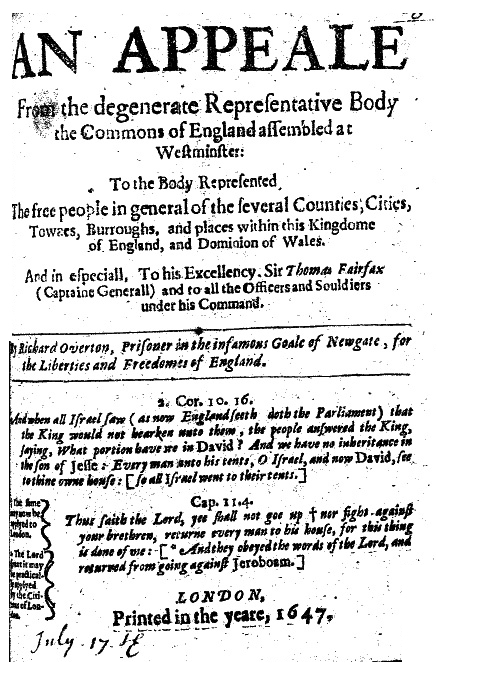

- 4.11. [Richard Overton], An Appeale from the degenerate Representative Body the Commons of England assembled at Westminster. (17 July 1647).

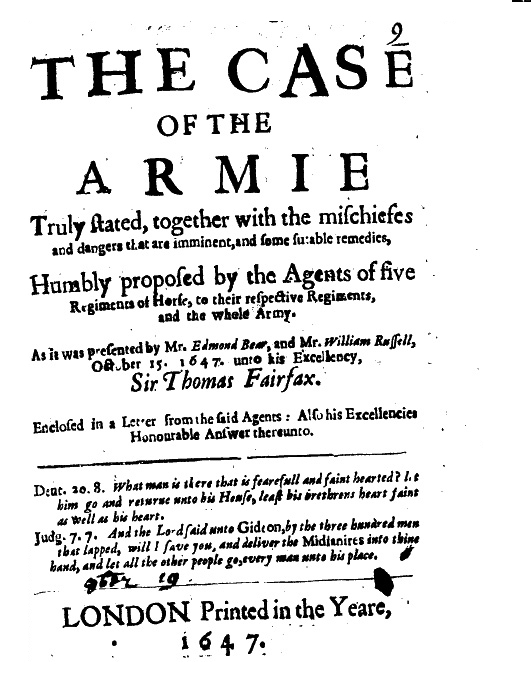

- 4.12. [Signed by Several People, but attributed to John Wildman], The Case of the Armie Truly stated (15 October 1647).

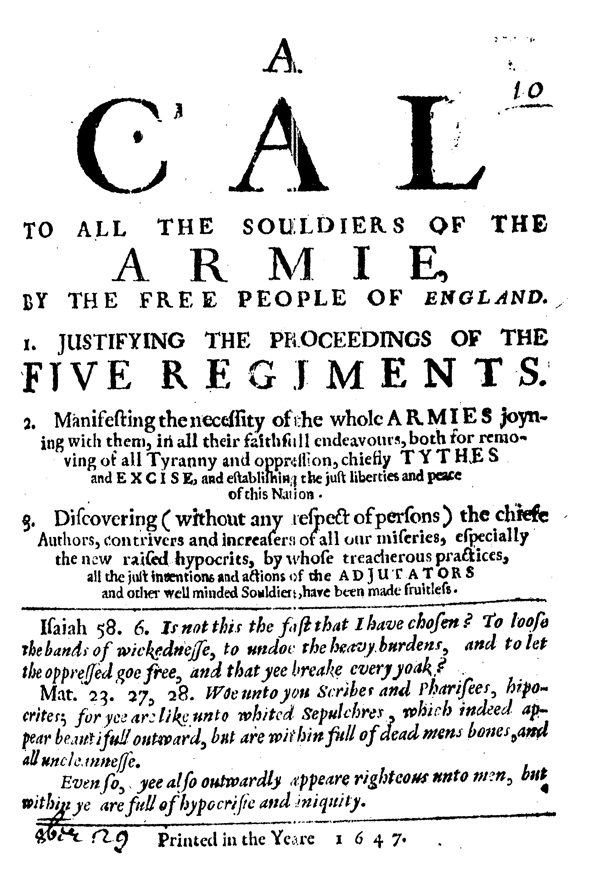

- 4.13. [John Wildman], A Cal to all the Souldiers of the Armie, by the Free People of England (29 October 1647). [9 illegibles]

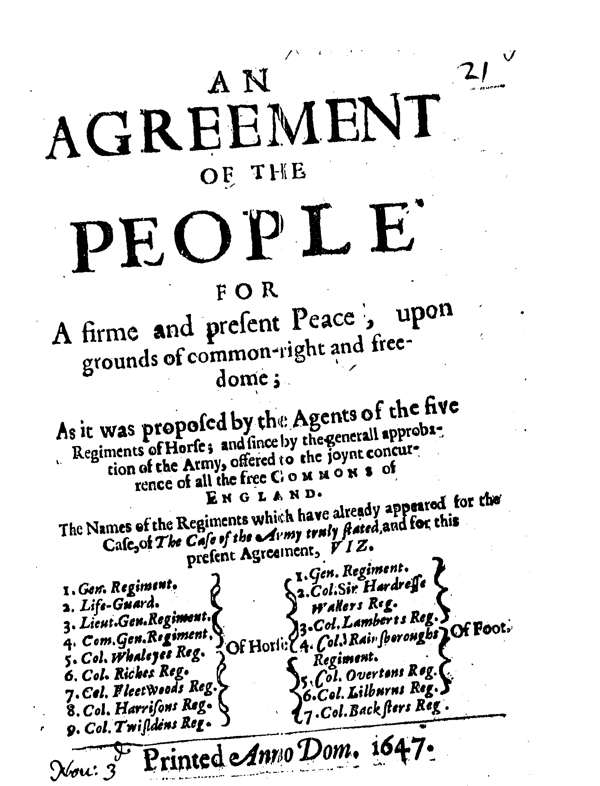

- 4.14. [Several Hands], An Agreement of the People for a firme and present Peace, upon grounds of common-right and freedome (3 November 1647).

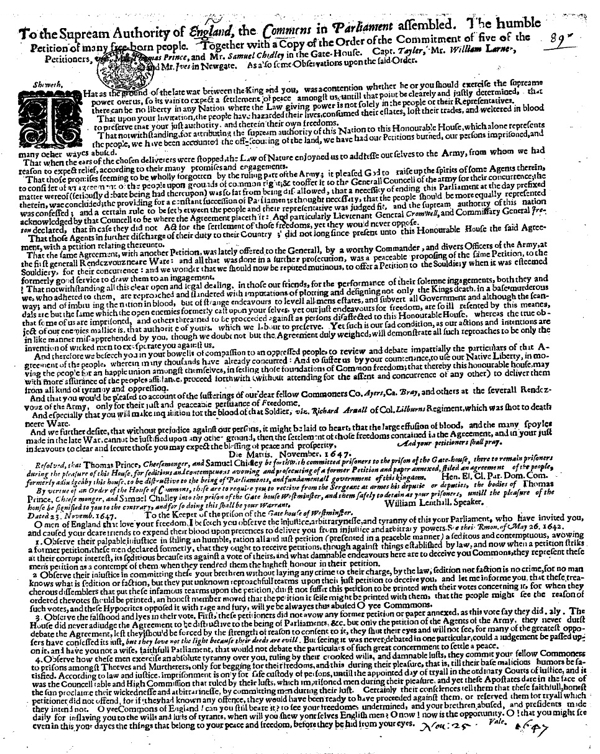

- 4.15. [Signed by Several], To the supream Authority of England, the Commons in Parliament assembled [The Petition of November] (23 November 1647).

- 4.16. [Several Hands], “The Putney Debates”, The General Council of Officers at Putney. (October/November 1647) [elsewhere in the OLL]

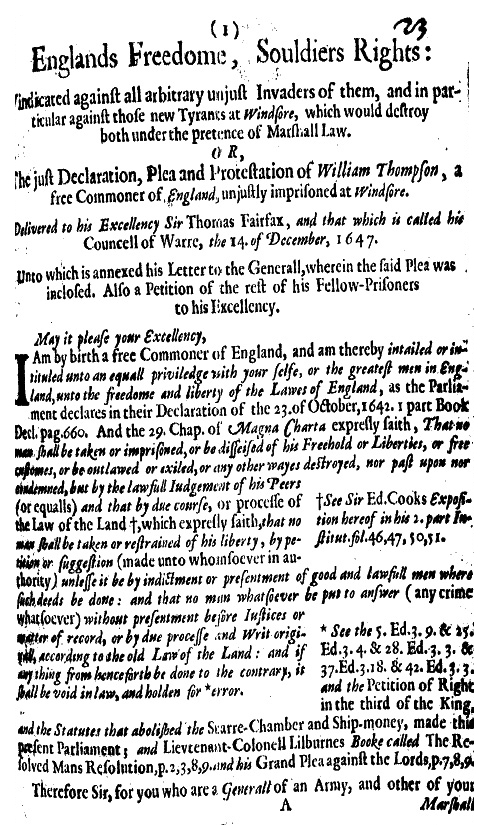

- 4.17. [Signed by Several, attributed to John Lilburne], Englands Freedome, Souldiers Rights (14 December 1647).

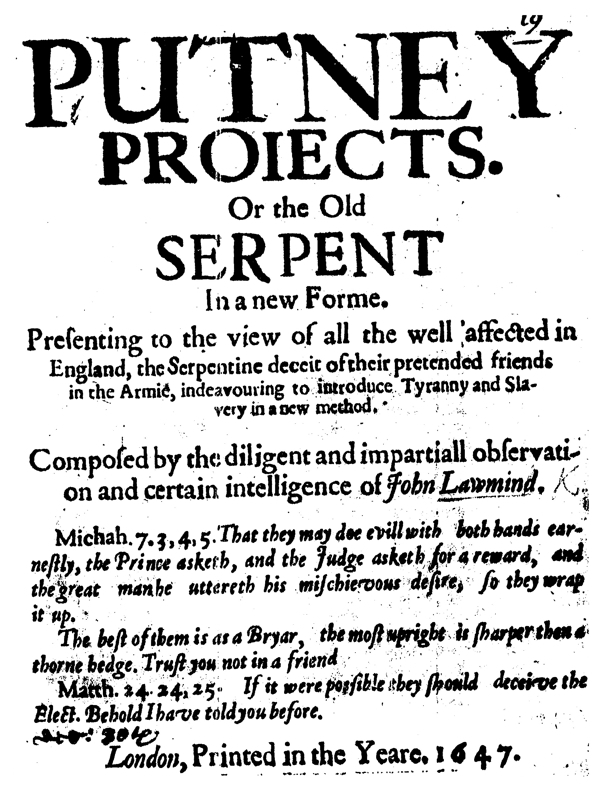

- 4.18. John Wildman (with William Walwyn), Putney Projects. Or the Old Serpent in a new Forme (30 December 1647). [254 illegibles]

Editor’s Introduction to Volume 4 (1647)↩

[to be added later]

Publishing and Biographical Information

Publishing information about each title can be found in the catalog of the George Thomason collection (henceforth "TT" for Thomason Tracts). Each tract is given a catalog number and a date when the item came into his possession (thus not necessarily the date of publication). We have used these dates to organise our collection in rough chronological order:

Catalogue of the Pamphlets, Books, Newspapers, and Manuscripts relating to the Civil War, the Commonwealth, and Restoration, collected by George Thomason, 1640-1661. 2 vols. (London: William Cowper and Sons, 1908).

- Vol. 1. Catalogue of the Collection, 1640-1652 [PDF

only] .

- Vol. 2. Catalogue of the Collection, 1653-1661. Newspapers. Index. [PDF only]

Biographical information about the authors can be found in the Biographical Dictionary of British Radicals in the Seventeenth Century, ed. Richard L. Greaves and Robert Zeller (Brighton, Sussex: The Harvester Press, 1982-84), 3 vols.

- Volume I: A-F

- Volume II: G-O

- Volume III: P-Z

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

The texts are in the public domain.

This material is put online to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. Unless otherwise stated in the Copyright Information section above, this material may be used freely for educational and academic purposes. It may not be used in any way for profit.

Tracts from 1647 (Volume 4)

4.1. John Lilburne, Regall Tyrannie discovered: Or, A Discourse, shewing that all lawfull (approbational) instituted power by God amongst men, is by common agreement, and mutual consent. (6 January 1647)↩

Bibliographical Information

Full titleJohn Lilburne, Regall Tyrannie discovered: Or, A Discourse, shewing that all lawfull (approbational) instituted power by God amongst men, is by common agreement, and mutual consent. Which power (in the hands of whomsoever) ought alwayes to be exercised for the good, benefit, and welfare of the Trusters, and never ought other wise to be administered: Which, whensoever it is, it is justly resistable and revokeable; It being against the light of Nature and reason, and the end wherefore God endowed Man with understanding, for any sort or generation of men to give so much power into the hands of any man or men whatsoever, as to enable them to destroy them, or to suffer such a kind of power to be excercised over them, by any man or men, that shal assume it unto himself, either by the sword, or any other kind of way. In which is also punctually declared, The Tyrannie of the Kings of England, from the dayes of William the Invader and Robber, and Tyrant, alias the Conqueror, to this present King Charles, Who is plainly proved to be worse, and more tyrannicall then any of his Predecessors, and deserves a more severe punishment from the hands of this present Parliament, then either of the dethroned Kings, Edw. 2. or Rich. 2. had from former Parliaments; which they are bound by duty and oath, without equivocation or colusion to inflict upon him, He being the greatest Delinquent in the three Kingdoms, and the head of all the rest. Out of which is drawn a Discourse, occasioned by the Tyrannie and Injustice inflicted by the Lords, upon that stout-faithful-lover of his Country, and constant Sufferer for the Liberties thereof, Lieut. Col. John Lilburn, now prisoner in the Tower.

In which these 4. following Positions are punctually handled.

1. That if it were granted that the Lords were a legall jurisdiction, and had a judicative power over the Commons; yet the manner of their dealing with Mr. Lilburn, was, and is illegall and unjust.

2. That the Lords by right are no Judicature at all.

3. That by Law and Right they are no Law makers.

4. That by Law and Right it is not in the power of the king, nor in the power of the House of Commons it selfe, to delegate the legislative power, either to the Lords divided, or conjoyned; no, nor to any other person or persons whatever.

Vnto which is annexed a little touch, upon some palbable miscarriages, of some rotten Members of the House of Commons: which House, is the absolute sole lawmaking, and law-binding Interest of England.

London, Printed Anno Dom. 1647.

Estimated date of publication6 January 1647.

Thomason Tracts Catalog informationTT1, p. 486; Thomason E. 370. (12.)

Editor’s Introduction

(Placeholder: Text will be added later.)

Text of Pamphlet

The Printer to the Reader.

IF thou beest courteous, Reader, contribute but thy Clemency in favourable correctiting the Errata’s (notwithstanding much due care had in so publike a work as this is) as we must acknowledge lye dispersed therin. Pag. 1. line 2. for 32. read 33. p. 4. l. 11. for fifthly r. sixthly. p. 7. 59. r. in the world; see Hof. 8. 4 p. 8. l. 17. for they r. he knowing that when he. p. 10. l. 20. for Rom. r. revelation. l. 29. r. Dan. 43. p. 11. l. 6. for against, r. but by. l. 38. for name, r. hand, p. 12. l. 2. r. and as he. l. 16. for 23. r. 33. l. 38. for his, r. their. p. 13. l. 24 for ver. 11, r chap. 8. ver. 11. p. 15. l. 30. for trivial, r cruel, p. 16. l. 2. for rule r. cover. p. 18. l. 16 for and his, r. and her. p. 19. l. 34. for rerforme, r. performe. p. 21. l. 1. blot out, years of his. l. 27. for this, r. of this King. l. 31. for most &, r. most base &. p. 23. l. 4. for 16. r. 6. p. 24. l. 10. for them, r. him. l. 25. for Realm granted him the ninth peny, r Realm dear, besides the 9. peny they granted formerly at one time for them to his Predecessor. p. 26. l. 20. r have had. l. 31. r. unusuall. l. 35. r. after this. p. 27. l. 2. r. uncounselable. l. 26 r late King. p. 34. l. 3. 457, r 655. l. 6, 264 r 462, p. 39, l. 26, after Charles, r but all his Predecessors received their Crown and Kingdom, conditionally by contract & agreement, I doubt not but the present K. Ch, his &c. p. 40, l. 10. r. by, but a, l 8, after King do, r & that there shold not much more be an account of his Office due to this Kingdom it selfe. p. 45, l. 23 after people, r and comes lineally from no purer a fountain, and well-spring, then from their Predecessors, l 25 blot out Dukes. p, 48. l. 29. that, put in if after. p. 56. l. 8, 404, 406, r. 504, 506, p. 59, l. 34 1641, r. 1646. p. 60, l. 10, 2 Sam: 7: 13, r. 1 King 12: 1. p. 61, l. 17, at the end of justly, r. come by, and. l. 18. at the end of Prophet, r. to K. Rehoboam. (who had assembled 18000. chosen men, which were Warriers to go fight against the house of Israel) p. 72, l. 2, in the margent for 254 r, 264, l. last of the marg, for 4, r. 467, p. 73, l. 15. 16 marg. after 29, insert 46. after Rot. 2, insert 4, p. 75, l. 1, in marg. for 5, r. 9, 4, for 8. r. 18, in marg. for 27. r. 2 part, l. 9. for 58, r. 38. p. 76, l, 19, for own r. other, p. 77, l. 9. in marg, 22 r. 102. p. 79, l. 1. abeas r. Habeas, p. 81, l. 24, r. to deliver to, l. 35, r. at which, p. 84. l. 2, after his honesty, r. his judges cariage, l. 7, for Lordships r. Lobby, p. 86, l. 26 blot out Dukes, p: 87: l: 1: practises r. prises, p. 88, l. 9. King r. Duke, p 91, l. 13. r. and afterwards in England made Odo, p. 92. l. 2. & 3. r. of whose estate l. 36. for unindivalid, r. unvalid, p. 94. l. 21. r. conquirendum, & tenendem sibi & here dibus, adeo libere per gladium sicut ipse rex tenhit Anglia. p. 95. l. 36. r. Comissioners, p. 96. l. 27. for incursion, r. innovation. p. 97. l. 23. r. But in the Knights, p. 97. l. 3. in the marg. for 84, r. 8, 4, 7. p. 98. l. 8. for nor r. for, p. 101, l. 12. for 1646. r. 1645.

A Table of the principall Matters contained in this ensuing Discourse.

A

ANger of God against Israel for their choice of a King, pag. 14.

Abuses checkt, pag. 25.

Acts of the Parliament, pag. 33.

Appeal of Lieut. Col. Lilburn to the House of Commons, how approved on there, pag. 64.

Arlet the Whore, William the Conquerers Dam, page 87.

Arlet the Whore marryed to a Norman Gentleman of mean substance, pag. 91.

B.

Bastardly Fountain of Englands Kings, pag. 15.

Bellamy pag. 1. his basenesse, pag. 2, 3.

Bookes of L. C. Iohn Lilburn before, pag. 3. and since the Parliament, pag. 3, 4, 89.

Books against L. C. Lilburn, p. 1. 4.

Barons Wars, p. 30, 31.

Behaviour of L. C. Lilburn in the House of Lords, p. 64, 65, 69.

Barons in Parliament represent but their own persons, p. 97.

C

Challenges against the Lords, p. 5, pag. 70.

Clergy base inslavers of this land of old, p. 89, 90, 93, 94.

Contents of this Discourse, p. 6, 62.

Common-Councel, p. 27.

Charles Stewarts jugling, pag. 50, 51.

Charles Stewart, not GOD, but a meer man, and must not rule by his will, nor other Kings, but by a Law, pag. 9 10, 11.

Charles Stewart received his Crown and Kingdom by contract, p. 33. and hath broken his contract, pag. 9, 14, 41, 42, 43, 50, 51, 52, 57.

Charles Stewart confuted in His vain proud words, p. 32, 33.

Charles Stewarts Confession and Speeches against himself, p. 40, 41, 56, 57.

Charles Stewart as Charles Stewart, different from the King as King, p. 35.

Charles Stewart guilty of Treason, p. 52, 53, 54, 55, 57.

C.R. ought to be executed, p. 57.

D

Dukes of Normandy, first, second, third, fourth, fifth, sixth, and seventh, p. 87.

Dukes, Marquesles, and Viscounts not in England, when the great Charter was made, p. 98.

Davies Sir I. Clotworthies friend his basenesse, pag. 102, 103, 104, 105, 106.

E

Edwardus Rex Segnier, pag. 15, 16, 88.

His gallant Law, p. 16.

Edward the second, p. 26, 27, 57, 58 deposed, and his eldest Son chosen, p. 27, 58, 59.

Edward the third, pag. 27, 28, 29, 30.

Excommunication for infringing Magna Charta, p. 28.

Edward 4. and 5. p. 30, 31.

Earl of Manchesters, and Colonel Kings basenesse, p. 49. 102.

Englishmen made slaves by the Normans, p. 90.

F

False imprisonment it is, to detain the prisoner longer then he ought, p. 81.

| First Duke, } | >p. 98. |

| First Marquesse, } | |

| First Viscount. } |

First Parliament, in the 19 of H. 1. see pag. 17.

G

Government by Kings, the worst government of any lawfull Magistracie, p. 14.

Greenland Company oppressors, pag. 101.

H

Heathens more reasonable then the Lords, p. 2.

House of Peers illegality, p. 43, 45, 86. and basenesse to the people, pag. 44.

Henry the 1. p. 17.

Henry, Mauds eldest son, King after Stephen, p. 19.

Henry the 3. crowned, and his basenesse, p. 22, 23.

Henry the 4, 5, 7, and 8. p. 30, 31.

Hunscot the Prelates Catchpole, now the Lords Darling, p. 83.

I

John brother to R. the 1. chosen King, p. 19.

His basenesse to the Commonwealth, p. 20, 21, 39.

His end, p. 22.

Judges corrupt, p. 23.

Imprisonment of L. C. Lilburn, p. 63, 66.

Ireland in her distressed condition cheated and couzened by Sir John Clotworthy, and his friend Davies, p. 102. to p. 106.

K

King is intrusted, p. 34.

Kings tyrannicall usurpation, none of Gods institution, pag. 7. 8.

Kings subordinate to Lawes, by God, p. 8. and men, p. 9, 18, 19, 23, 24, 26, 27, 28, 29, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 52, 53, 85, 86.

Kings must not be imposed, but by the peoples consents, p. 7, 20, 32, 41, 60, 61.

Kings deposed, p. 27, 58, 59, 98.

Knights, Citizens, and Burgesses represent the Lawes, p. 97.

King, no propriety in his Kingdome, p. 34. or Cities thereof, or Jewels of the Crown; and as King, not so much as the Subjects in the Kingdoms, pag. 32, 38.

Kings illegall Commands obeyed punished, pag. 35, 52, 53, 54.

Kings are lyable to be punished. pag. 41, 59.

K. Harrold, p. 84, 94.

L

Lawes made this Parliament, pag. 33, 34.

Lieutenant of the Towers basenesse against L. C. Lilburn, pag. 5.48.

Lords cause of loosing the Kingdome at first, p. 93.

Lords no legislative power by consent of the people, p. 45, 46.

Lords may not lawfully sit in the house of Commons, pag. 98, 99.

Lords contradict themselves, p. 63.

Lords power wholly cashiered, p. 40, 47, 92.

Lords overthrown by the Law, see p. 72. to p. 78.

Lords illegality and basenesse against L. C. Lilburn, pag. 47, 48, 65, 66, 67, 84. proved so to be, p. 62, 81.

Lords no Judges according to Law, p. 69.

Lawes included, though not expressed, Kings must not violate, pag. 62.

Lords no Judicature at all, p. 84, 85, 86.

M

Maud p. 17, 18. the Empresse taketh K. Stephen in bat- tel, p. 18.

Massacre of the Jewes in England when pag. 19.

Magna Charta, what it is, p. 26.

Magna Charta’s Liberties confirmed by Hen. the 3. p. 24.

And by Edw. the 2. p. 27. And by Edw. the 3. p. 28, 29.

Members of the House of Commons taxed, p. 100, 101, 102.

Merchant-Adventures p. 99. overthrown, p. 42.

N

Normans whence they came, pag. 86, 87.

Ninety seven thousand, one hundred ninety and five pounds, which was for Ireland, pursed by 4 or 5 private men; see p. 103.

O

Orders Arbytrary and illegall against L. C. Lilburn, p. 2, 47, 48. 63, 64, 66.

Odo the Bishop, & a Bastard seeketh to be Pope, pilleth the Kingdom pag. 91, 92.

Oaths of Kings at their Coronation, p. 19, 26, 28, 31, 32, 33.

Oath of K. Stephen p. 18.

Oath of Justices, p. 29.

Objection about H. 8. alteration of the Oath of Coronation, answered by the Parliament, p. 32.

Order of the house of Commons for L. C. Lilburn, p. 84.

Originall of the House of Peeres pretended power, p. 94.

P

Petition of Right confirmed, p. 33. the Lords break it, p. 2.

Petition of L. C. Lilburns wife p. 72. to p. 78.

Postscript of L. C. Lilburns, p. 6.

People must give Lawes to the King, not the King to the people, p. 85.

Popes judgment refused by the people, to be undergone by the King as insufferable, p. 26.

Power of Lords both of judicative and legislative throwne down, p. 92, 93.

Parliament, what it is, p. 34. their institution, p. 95. The manner of holding them, p. 95. how kept, p. 97.

Parliaments greatnesse p. 34, 36, 37.

Prerogative Peerageflowed from rogues, p. 86, 87.

Proceedings of the Lords against L. C. Lilburn, condemned by the Commons, p. 64.

Parliaments kept in old time without Bishops, Earles, or Barons, Pag. 96, 97.

Q

Questions of great consequence, pag. 101, 102.

R

Rehoboams folly, pag. 60, 61.

Richard the 1. pag. 19.

Remedy against frand, p. 26.

Richard the 2. p. 30.

Deposed p. 30.

Richard the 3. p. 30, 31.

Rebellion of the King. 90, 51.

Rewards conferred by William the Conqueror, upon his assistants, p. 90, 91.

S

Sir John Clatworthies basenesse, p. 102. to 106.

Stephen Earle of Bollaigne chosen King by free election, p. 18.

When hee was imprisoned by Maud, p. 18, 19. the people restituted him out, and he was set up again, p. 18.

Sheriffes of London; Foot and Kendrick their illegality, pag. 68.

Sentence of the Lords against L. C. Lilburn. p. 70, 71.

T

Ten Commandements explained, p. 9, 10.

Tyrants (Kings) plagued by Gods justice, p. 11, 12, 13, 17.

Tyrannie of Kings, p. 13, 17, 19, 20, 21, 22.

Towers chargeablenesse of Fees, p. 49.

Tryals ought to be publike, and examples for it, page 81, 82, 83, 84.

Turkie Merchants, pag. 99.

W

William the Conquerors History of him, p. 14, 15, 16, 45, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, a Bastard, p. 87.

His end, p. 17.

Westminster Halls inslaving Lawes, Judges, Practises, from William the Tyrants will, pag. 15, 16.

William the 2. p. 17.

Wayes for purchasing liberty and annihilating of the Norman Innovations, p. 25, 29.

Wollastons Letter from L. C. Lilburn, p. 67, 68.

Writs, Warrants, and Mittimusses, how they ought to be made in their formes in the severall Courts, p. 78, 79, 80, 81.

IT is the saying of the God of Truth, by the Prophet, Isa: 32. 15, 16. That he that walketh righteously, and speaketh uprightly, he that despiseth the gain of oppressions, that shaketh his hands from holding of bribes, that stoppeth his eares from hearing of bloud, and shutteth his eyes from seeing of evill; He shall dwell on high, his place of defence shall be the Munition of Rocks, &c. But on the contrary, he saith; Woe unto them that decree unrighteous Decrees, and that write grievousnesse which they have prescribed, to turn aside the needy from judgment, and to take away the right from the poore of my people, that widowes may be their prey, and that they may rob the Fatherlesse, Chap. 10. 1, 2 Now I, having read over A Book Intitvled, The Freemans Freedome Vindicated, being Lieutenant-Colonell John Lilborns Narative of the Lords late dealing with him, in committing him to New-Gate; and seriously considering of his condition, and of the many base aspersions cast upon him, and bitter invectives uttered against him in some late printed Bookes, but especially that of Colonell John Bellamies, called, A Vindication of the City Remonstrance; which came our, when he was a close prisoner in Newgate, by vertue of as cruell, unjust, and illegal a Warrant as ever was made by those that professe themselves to be conservators of the peoples liberties; yea, and I dare say, that search all the Records of Parliament, since the first day that ever there was any in England, and you shall not find the fellow of that which is against him; The Copy of which (as I find it in that of the JVST MAN IN BONDS) thus followeth;

Die Martiis, 23. Junii, 1646.

ORdered by the Lords in Parliament assembled, That John Lilburn shall stand committed close prisoner in the &illegible; of Newgate; and that he be not permitted to have Pen, Inke, or &illegible; and &illegible; shall have accesse unto him in any kind, but onely his Keeper, untill this Court doth take further order. IOHN BROWN, Cler. Parliamentorum.

To the Keeper of Newgate, his Deputy, or Deputies, Exam. per Rad. Brisco, Cler. de Newgate.

What can be more fuller of arbytrary Tyrannie, and illegality then this Order expressing no cause, who, nor wherfore; & so not only absolutely against the expresse tenour of the Petition of Right, but contrary to the very practice of the Heathen Romanes, who it seemes had more morallity, reason, and justice in them, then these (pretended Christian) Lords: see Acts 25-27. For saith Festus to King Agrippa &c. When he was to send Paul a prisoner to Rome, It seemeth to me unreasonable to send a prisoner, and not with all, to Significatio Crimes laid against him.

And although that this Arbitrary & illegal Order was extraordinary harshly executed upon Mr. Lilburn, and thereby he was as it were tyed hand and foot; yet then did Mr. Bellamie watch his opportunity to insult over him, when he knew that he was not able to answer for himself. O the height of basenesse! for a Colonell to be so void of manhood, and to finde no time to beat or insult over a man, but when he is down, and also tyed hand and foot!

One thing in Mr. Bellamies Book I cannot but take notice of especially, and that is this; He there cites some things in a Book called ENGLANDS BIRTH-RIGHT; and because it hath very high language in it, against divers great, and corrupt Members of Parliament, which is sufficient to destroy and crush the Author of it in pieces, if he were known: And therefore that he might load Mr. Lilburn to the purpose, he takes it for granted, that Book is his, although his name be not to it, nor one argument, or circumstance mentioned to prove it his; but the absence of his name, is a sufficient ground to all that knowes him and his resolution, to judge Mr. Bellamy a malitious Lyar in that particular; I being Mr. Lilburns common practice (for any thing I can perceive) to set his name to his Bookes, both in the BBs. days, and since; which Bookes contain the highest language, against the streame of he Times, that I have read, of any mans in England that avouch what he writes. As for instance, His Book, called THE CHRISTIAN MANS TRY ALL, being a Narrative of the illegality of the Star-Chambers dealing with him, and the barbarous inflicting of their bloudy sentence upon him.

Secondly, His Book called, COME OVT OF HER MY PEOPLE, written (it seemes) when he was in Chaines, the fullest of resolution that I have read.

Thirdly, THE AFFLICTED MANS COMPLAINT, written, when he was sick in his close imprisonmen, by reason of his long lying in Irons.

Fourthly, his Epistle to Sir MAVRICE ABBOT, then Lord Major of London, called, ACRY FOR JVSTICE.

Fifthly, his Epistle to the PRENTICES OF LONDON; In both of which, he accuseth the Bishop of Canterbury, offing Treason, and offered, upon the losse of his life, to prove it, when Canterbury was in the height of his glory.

Sixthly, his Home Epistle to the Wardens of the Fleet, when he was in their own custody, and forced to defend his life, and chamber for divers work &illegible; with a couple of Rapiers, against the Wardens and all his men, who had like, several times, to have murdered Mr. Lilburn.

Seventhly, his Answer to the nine Arguments of T. B. which laves lead enough upon the old and new Clergie, the rooters up of Kingdomes and States.

And since the Parliament.

First, His Epistle to Mr. Pryn, which both gaules him, and the Assembly, the thunder-bolt of England.

Secondly, His Reasons against Mr. Pryn, delivered at the Committee of Examinations.

Thirdly, His Epistle wrote when he was in the custody of the Serjeant at Armes, of the House of Commons, which toucheth not a little the corruptnesse acted in that House.

Fourthly, His Answer to Mr. Pryn, in ten sheets of Paper, called INNOCENCIE AND TRUTH JUSTIFIED, a notable and unanswerable piece.

Fifthly, His Epistle to Judge Reeves, called, THE JUST MANS JUSTIFICATION.

Fifthly, His PROTESTATION AGAINST THE LORDS, AND APPEALE TO THE HOUSE OF COMMONS.

Seventhly, His EPISTLE to the Keeper of Newgate, dated from his Cock-loft in the Presse-yard of Newgate, the 23. of June, 1646.

The next Bookes that I have lately seen against L. C. Lilburn, are two rayling ones, made by one S. Shepheard, a fellow as full of simplicity as malice; In both whose Bookes, there is not one Argument, or one sound reason, to disprove, what he pretends to confute. The first of his Bookes, is called, The Famers famed, or an answer to three things written (it seemes) by some of Mr. Lilburns friends, called, First, THE JUST MAN IN BONDS. The second, A PEARL IN A DVNGHILL. The third, A REMONSTRANCE OF MANY THOUSAND CITIZENS, and other Free-born People of England, to their own House of Commons, &c. The second of Shepheards, is called, The false Allarme; or, an Answer to an Allarme, To the House of Lords. The fourth Pamplet I find against L. C. Lilburn, is called Plain English, which last, only gives him two wipes, in his 4. and 12. pages.

Therefore, in regard that the Author of the City Remonstrance Remonstrated, hath put Pen to Paper, to answer part of Mr. Bellamies Book, but hath not medled with any thing of that which doth concern Lieut. Col. Lilburn.

And secondly, Forasmuch, as none that is yet visible have medled with any of the other.

And thirdly, In regard that the man is full of Heroicalnesse, and a zealous lover of his Country, to whom all the honest free-men of England, are extraordinarily oblieged, for his constant, couragious, and faithfull standing, for their just liberties, that both God, Nature, and the Law of the Land giveth them.

And partly in regard that by a late published Book, called, LIBERTY VINDICATED AGAINST SLAVERY, I understand of the Lieutenant of the Towers base, unworthy, illegall, and strict dealing with him, as in many other things, so in keeping him from Pen and Ink; by meanes of which, he is unable to speak publikely for himself, which is a sad, barbarous, base, and inhumane case. That a man should be so illegally dealt with, as he is, and abused in print, and his good name endeavoured Cum privilegio, to be taken away by every Rascall, and yet the poor man not suffered to speak a word for himself. Oh! horrible and monstrous age, that dare without remorse maintain such horrible impiety, and injustice: Surely, I may well say of them, with the Prophe. Isa. Isa 5. 20, 23, 24, Woe unto them that call evill good, and good evill, that put darkness for light, and light for darknesse, that put bitter for sweet, and sweet for bitter, which justifie the wicked for reward, and take away the righteousnesse of the righteous foom him. Therefore as the fire devoureth the stubble; and the flame consumeth the chaffe; so their root shall be rottennesse, and their blossome shall go up as dust; because they have cast away the Law of Jehovah of Hosts, and despised the Word of the holy One of Israel: For he that justifieth the wicked, and he that condemneth the just; even they both are an abomination to Jehovah, Prov. 17. 15.

In consideration of all which, together with many more things I shall endeavour (according to that insight I have) in Mr. Lilburnes behalf, to make a little more work, for his enemies, the Lords, and their Associates; But this (as a faire adversary) I shall advise them, either to get stouter Champions that can handle their weapons better then those that have yet appeared, or else their cause will utterly be lost.

I shall not now undertake to answer the particulars in the forementioned Bookes, but leave that to another Pen, and shall give a home provocation, to the best and ablest Lord in England, or the choicest Champion they have, to produce some sound arguments to maintain their jurisdiction, or else their two stooles (called Usurpation and custome) upon which they sit, will let them fall to the ground.

And the method that I shall observe, shall be this:

First, I will prove, that if it were granted, that the Lords were a &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; and had a judicatine power over the Commons, yet the therefor of the Lords dealing with him is illegall and unjust.

Secondly, I will prove that in the Lords were a Judicature, yet they &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; &illegible;

Third, I will give some reasons to manifest, that they are no &illegible; &illegible;

Fourthly, That they by Law and Right, are no Law-makers.

Fifthly, That by Law and Right, it &illegible; not in the power of tho &illegible; &illegible; the House of &illegible; &illegible; to deligate the legislative power, either to the &illegible; &illegible; or &illegible; nor to any other persons &illegible;

Now for the proofe of these; &illegible; &illegible; I shall make use of, &illegible; &illegible; be derived from Scripture.

Secondly, from the &illegible; &illegible; strength of sound reason.

Thirdly, from the &illegible; St. &illegible; Law of the Kingdome.

Fourthly, from &illegible; &illegible; Parliaments Declarations.

Fifthly, &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; of England, licenced by publike Authority.

And that I may not raise a &illegible; with &illegible; laying a good Foundation, I will set &illegible; &illegible; and undeniable position, which I &illegible; a &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; latter end of &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; printed Protestation against the Lords; which is &illegible;

GOD, the absolute Sovereignty Lord and King, of all things in heaven and earth, &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; and &illegible; all causes, who is &illegible; &illegible; and &illegible; by no rules, but &illegible; all things &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; will and unlimitted good &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; and all things therein, for his &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; will &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; man (his &illegible; &illegible;) the &illegible; &illegible; (&illegible; &illegible; &illegible;) overall the rest of his creatures, &illegible; 1. 26, 28. 29. and &illegible; &illegible; with a &illegible; &illegible; or &illegible; &illegible; a &illegible; &illegible; matter his own image, &illegible; 1. &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; first of which was Adam, a &illegible; or man, &illegible; of the &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; out of &illegible; side was &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; mighty creating power of God, was &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; called &illegible; which two are the earthly, original &illegible; as &illegible; and bringers &illegible; all and every particular and individuall man, and woman, that ever breathed in the world since, who are, and were, b. nature and alike in power, dignity, authority, and majesty, none of them having any authority, dominion, or magist real power, one over, or aboue another, but by institution, or &illegible; that is to say, by &illegible; agreement or consent given, derived, or assumed by &illegible; &illegible; and agreement, for the good, benefit, and comfort each of other, and not for the &illegible; &illegible; or damage of &illegible; it being &illegible; irrationall, &illegible; wicked and unjust for &illegible; &illegible; or men whatsoever, to part &illegible; so much of their power, &illegible; shall enable any of their Parliament men, Commissioners, Trustees, Deputies, Viceroyes, Ministers, Officers, and &illegible; to destroy and &illegible; them therewith: And &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; just, divillish and &illegible; it is for any man whatsoever, &illegible; or &illegible; Clergy-men or &illegible; to appropriate and assume &illegible; him else, a power, authority, &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; rule, govern, or raigne over any sort of men in the world, without their &illegible; consent, and whosoever &illegible; &illegible; whether Clergy-men, or any other whatsoever, do thereby as much as in them &illegible; &illegible; to appropriate and assume &illegible; themselves the Office and Soveraignty of GOD, (who alone doth, and is to rule by his &illegible; and pleasure) and to be like their Creator &illegible; was the &illegible; of the &illegible; who not being content with their first station, but would be like GOD; for which &illegible; they were throwne downe into &illegible; reserved in everlasting &illegible; under darkenesse, unto the judgement of the great day, Iude—vers. 6. And Adams sin it was &illegible; brought the &illegible; &illegible; him and all his &illegible; that he was not content with the &illegible; and condition that God created him in; but did aspire unto a better, and more excellent (namely to be like his Creator) which proved his ruine, yea, and indeed had been the everlasting ruin & destruction of him and all his, had not GOD been the more merciful unto him in the promised Messiah. Gen. Chap. 3.

Now for the government of England; It hath been by custome principally and for the most part by the tyrannicall usurpation of a King, and therefore it will be requisite to search into the Scripture, and see, whether ever GOD approbationally &illegible; it, or onely permissively suffered it to be, as he doth all the other evils and wickednesse in the world, and for the better understanding of this, It is requisite, to remember that we find in Scripture, That God was not only Israels husband, and did perform all the offices of a loving husband in his sweet and cordiall embracements of her, and loving dispensations to her, but also he was her KING himself, to raign and rule over her, and to protect and defend her, and being the Lord Almighty, and knowing all things past, present and to come, knew well that Israel would be forgetfull of all his kindnesse; and though he had chosen them out of all the world in a speciall manner to be his peculiar ones; yet they would forsake him, and desire to be like the World; And Moses declares thus much of them after they had enjoyed the good things of God in abundance: But Jesurun waxed fat, and kicked: Thou art waxed fat, thou art grown thicke, thou art covered with fatnesse: then he forsook God which made him, and lightly esteemed the Rock of his salvation, Deut. 32. 15.

And therefore they knowing that when he possessed the Land of Canaan, they would reject him, and desire a King (like all the rest of the Heathens, and Pagans) to reign over them: Yet they being dear unto him, he would not wholly reject them, but gave them a Law for the chusing of a King, and his behaviour, which we find in Deut. 17. 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20. in these words: When thou art ome into the Lands, which Jehovah by God giveth thee, and shalt possesse it, and shalt dwell therein, and shalt say, I will set a King over me, like as all the Nations that are about me. Thou shalt in any wise set him King over thee, whom Jehovah thy God shall chuse, one from among thy Brethren shalt thou set King over thee: Thou mayst not set a stranger over thee, which is not thy brother: But he shall not multiply horses to himself, nor cause the people to return to Egypt, (that is, to bondage or slavery;) to the end, that he should multiply horses: Forasmuch, as Jehovah hath said unto you, Ye shall henceforth return no more that way, (that is to say, &illegible; shall be no more slaves.) Neither shall he multiply wives to himself, that his heart turn not away; neither shall greatly multiply to himself silver and Gold. And it shall be when he &illegible; upon the &illegible; of his Kingdom, that he shall write him a Copy of this Law in a Book, out of that which is before the Priests, the Levites. And it shall be with him, and he shall reade therein all the dayes of his life, that he may learn to leave Jehovah his God, to keepe all the words of this Law, and these Statutes, and do them; That his heart be not lifted up above his Brethren, and that he turn not aside from the Commandement, to the right hand, or to the left; to the end, that he may prolong his dayes in his Kingdome, he and his children in the middest of Israel. So that to me it is very cleer, that all Government whatsoever ought to be by mutuall consent and agreement; and that no Governour, Officer, King, or Magistrate, ought to be be trusted with such a Power, as inables him when he pleaseth, to destroy those that trust him; And wickedness [in the highest] it is for any King, &c. to raign and govern by his Prerogative; that is to say, by his will and pleasure, and as great wickednesse it is for any sort of men, to suffer him so to do: For the proofe of this, I lay down my Argument thus, and we will apply it to the King of England in perticular.

He that is not GOD, but a meer man, cannot make his will, a rule, and law, unto himself and others.

But Charles Stewart, (alias Charles Rex.) is not God but a meer man.

Ergo, he cannot make his Will a rule and Law unto himselfe or to the people, of England:

Secondly, He that by contract and agreement receives a Crowne or Kingdome; is bound to that contract and agreement the violating of which, absolves and disingages those, (that made it) from him,

But King Charles received His Crowne and Kingdome by a contract, and agreement, and hath broken His contract and agreement.

Ergo. &c.

Now for the clearing of the first proposition, it is confest by all that are not meer Athists, That GOD alone rules, and governs by his Will, and that therefore things are legall, just, and good: Because GOD wills them to be so. And therefore all men whatsoever must, and ought to be ruled by the Law of GOD, which in a great part is engraven in Nature, and demonstrated by Reason: As for instance, It is an instinct in Nature, that there is a GOD, Rom. 1. or a mighty incomprehensible power. (And therefore it is rationall, that we should not make Gods unto our selves,) and this is the pith of the first Commandement. Nature telling me, There is a God. And therefore secondly, its rationall he only should be worshipped, served, and odored, and that’s the marrow of the second Commandement. And in the third place, seeing nature tells me there is a GOD, reason &illegible; unto me, that I should speak reverently and honourably of him; And this is the summe of the third Commandement. Fourthly Nature dictating to me, there is a GOD. It is rationall I should set some time apart to do him homage and service;

And seeing the instinct of Nature causes me to look upon him as a Soveraign over me; is but rationall hath he should appoint a Law unto me, for the matter manner, and time of his worship and service; and this is the substance of the fourth Commandement.

Again, seeing nature teacheth me to defend my self, and preserve my life; Reason telleth me in the &illegible; &illegible; it is but just that I should not doe that unto another, which I would not have another doe to me; but that in the affirmative, I should do as I would be done unto; And this is the marrow of the whole second Table of gods Law, from whence, all Lawes amongst men ought to have their detivation: And therefore, because by nature no man is GOD, or Soveraign, one over another; Reason tells me, I ought not to have a law imposed upon me, without my consent; the doing of which is meerly tyrannicall, Antichristian, and Diabolicall, Rom. 13. Yea Reason tells me in this that no Soveraignty can justly be exercised, nor no Law rightfully imposed, but what is given by common consent, in which, every individuall is included; So this proves the latter part of the Argument.

As for the minor Proposition, I think it will not be denied; for I conceive, none that confesse Christ to be come in the fifth will be so Atheisticall, as to affirme the King to be any more then a meer man, subject to the like infirmities with other men; See Acts 12. 22, 23. Dan. 14. 22, 25, 33. and 5. 18, 20, 23.

As touching the second Argument, the whole Current of the Scripture prove their, In all the Contracts betwixt GOD and his Creatures. As for instance:

First, with Adam, who by Gods contract (being his Soveraign) was to enjoy Paradice, &c. upon such, and such a condition; but as soon as Adam broke the agreement, GOD took the forfeiture, see Gen. 3. 16, 17, 24. So likewise GOD made a contract with &illegible; when he gave the Law in Mount Syna (as their LORD and KING) by the hand of Moses: But when they broke their Covenant, God took the forfeiture, though he being a Soveraigne Lord, and governed by nothing but his own Will, forbore long the finall execution of the forfeiture: So in the same case amongst the Sons of Men, that live in mutuall society one amongst another in nature and reason, there is none above, or over another, against mutuall consent and agreement, and all the particulars or individuals knit and joyned together by mutuall consent and agreement, becomes a Soveraign Lord and King, and may create or set apart, for the execution of their Lawes (flowing from their will and mind founded upon the Law of God, ingraven in nature, and demonstrated by reason) Officers, which we call Magistrates, and limit them by what rules they judge convenient; alwayes provided, they be consonant to the Law of God, Nature, and Reason; by the force of which, it is not lawfull for any man to subject himself, to be a slave. For that which is against Nature, and the glory of the Image of God that he created man in, Gen. 9. 6. and so a dishonour to himself, and to his Maker, his absolute and alone Soveraign, cannot justly be done. But to subject to slavery, or to be a slave, is to degenerate from his Originall, and Primitive institution of a Man into the habit of a Beast, upon whom God never bestowed that stile of honour of being creatures created in the Image of their Creator.

And therefore, I am absolutely of Catoes mind, to think, that no man can be an honest man, but he that is a free man, And no man is a free man, but he that is a just man. And for any man in the world, whatsoever he be, that shal by his sword, or any other means thus assume unto himself, and exercise a power over any sorts of men, after this kind against their wills and mindes, is an absolute Tyrant and Monster, not of God, or mans making, but of the Divels linage and off-spring, (who is said to go up and down the world, seeking whom he may devour) who ought to be abhorred of God, and all good men, seeing that such Monsters, commonly called Kings &illegible; Monarks, assume unto themselves, the very Soveraignty, Stile, Office, and name of GOD himself, whose Soveraign Prerogative it is, only, and alone, to rule and govern by his will. Therefore when the Sons of men took upon them to execute in this kind, GOD raised up Moses his Servant, to deliver those whom he took delight in, from their tyranny, and to be an Instrument in his Name to ruine and destroy that grand Tyrant Pharoah, and all his Country, Exod. 3. 9, 10. and 5. 5. and 14. 5, 14. 25, 28.

As he journied towards Canaan, God by his Agents destroyed five (Vsurpers or Kings) more, at one bout, Num. 31. 8. and more at the next bout, Num: 32. 33. Deut: 3. 2. 3. And after him, the Lord raised up Ioshua, whom he filled full of the Spirit of Wisdome, Deut: 34. 9 to be his executioner upon such his pretending Competitors, Kings (alias Tyrants.) And the first that I read of was the King of Jericho, whom he destroyed Josh 6. 21. and 10. 28. And the next was the King of Ave, whose Citie and Inhabitants he utterly destroyed, and hanged their King on a tree, Josh 8. 26, 28, 29. The next after them was five Kings, with whom he waged bittell altogether, And when he had slain their people, he took the five Kings, and caused his Captains and men of war to tread upon their necks and afterwards he smote them, and slew them, and hanged them on five trees, Iosh 10. 26. The next he destroyed was the King of Makkedah, vers. 28. and vers. 29 he destroyed the King of Libnah, vers. 23. he destroyed the King of Gezer; and the next he destroyed was the King of Hebron, vers. 37. And then he utterly destroyed the King of Debir, and his City, vers. 39. and in chap. 11. Hazer sent to abundance of his neighbouring Kings, who assembled much people together, even as the sand that is upon the Sea-shore, (vers. 4) to fight against Joshua, who utterly destroyed them all vers. 12.—23. which in the next Chapter he enumerates; And after Joshua, the Lord chose Judah, to be his Executioner, &illegible; his Deputy, or Vice-Roy, that being a name and title high enough for any man, and the first piece of justice that Judah doth, is upon Adonibezek, who was a great and cruell King and Tyrant, and his thumbs and his great toes he cut off, who himself confessed it, a just hand of God upon him, himself having served threescore and ten Kings in the same manner, and made them gather their meat under his Table, Iudg. 1. 6, 7. But the children of Israel (&illegible; Subjects of GOD not onely by Creation, but also by Contract and Covenant) violating their Covenant with their Soveraigne LORD and KING, in not driving out, and utterly destroying the people of Gods indignation (who had robbed him of his Honour, as their Soveraign by creation in yeelding subjection to the wills and lusts of Tyrants, called their Kings, who had thereby usurped upon the peculiar Prerogative Royall of GOD himself, and so put both Tyrants (Kings) and Slaves (his Subjects) out of the protection of their Creator) wherefore they became unto them as thornes in their sides, Iudg. 2. 2, 3. and in a little time they began to rebell against their LORD, and his Lawes, which incensed his anger against them, and caused him to deliver them into the hands of Spoylers, and to sell them into the hands of their Enemies round about, Iudg. 2. 14 And in the 9 chapter Abemilech sought the Soveraignty over the people, and got it with the bloud and slaughter of threescore and ten of his Brethren, but GOD requited, with a witnesse, both on him, and all that had a finger in furthering of his usurpation, vers. 23, 24, 45, 53, 54 for afterward the Tyrant that they had set up destroyed them all for their pains, and in the end had his scull broke to pieces with a piece of a millstone thrown from the hand of a woman, And after many miseries sustained by the people of Israel, for their revolt from their loyalty to GOD, their LORD and KING: Yet in their distresse, hee took compassion of them, and sent them Samuel, a just and righteous Judge, who judged them justly all his dayes.

But the people of Israel like foolishmen, not being content with the Government of their Soveraign by Judges (who out of doubt took such a care of them, that he provided the best in the world for them) would reject their Liege Lord, and chuse one of their own; namely, a King, that so they might be like the Pagans and Heathens, who live without God in the world, which Act of theirs, God plainly declares was a rejection of him,1 Sam. 8. 7. and 10. 9. that he should not reign over them, 1 Sam. 8 7. and chap. 10. 19. But withal, he &illegible; vnto them the behaviour of the King, vers. 11, 12, 13, 14, 16. which is, that he will rule and govern them by his own will [just Tyrant like] for saith Samuel, he will take your Sons, and appoint them for himselfe for his Chariots, and to be his &illegible; and ome shall run before his Chariots, and he will take (by his Prerogative) your Fields, and your Vineyards, and your Oliveyards, even the best of them, and give them to his Servants, and he will take your men-servants, and your maid-servants, and your goodliest young-men, and your Asses, and put them to his worke, &c. And saith Samuel, you shall cry out in that day, because of your King, which ye shall have chosen unto you: but the Lord will not hear you in that day: And Samuel (in the 12. Chapter,) gives them positively the reason of it, which was, that although GOD in all their straights had taken compassion on them, and sent them deliveries, and at the last, had by himself, set them free on every side; so that they dwelt safely: Yet all this would not content them, but they would have a King to reigne over them, when (saith Samuel) The Lord your God was your King: therefore chap. 19. saith Samuel, ye have this day rejected your God, who himself saved you out of all your adversities, &c. yea, and (in the 19. ver. of the 12. chap.) the People acknowledged that they had added unto all their sins, this evill, even to ask a King; Whereb, we may evidently perceive, that this office of a King, is not in the least of Gods institution; neither is it to be given to any man upon earth: Because none must rule by his will but God alone; And therefore the Scripture saith, He gave them a King in his anger, and took him away in his wrath, Hosa 13. 11.

In the second place for the proofe of the minor Proposition, which is, That Charles R. received his Crown and Kingdome by contract and agreement; and hath broken his contract and agreement, I thus prove.

And first, for the first part of the position, History makes it clear, that WILLIAM THE CONQVEROVR, OR TYRANT, being a Bastard, subdued this Kingdome by force of Armes. Reade Speeds Chronicle, folio 413. There being slain in the first Battell, betwixt him and the English about sixty thousand men, on the English party, As Daniel records in his History, fol. 25. And having gained the Country, he ruled it by his sword, as an absolute Conqueror, professing that he was beholding to none for his Kingdome, but God and his sword, making his power as wide as his will (just Tyrant like) giving away the Lands of their Nobles to his Normans, laying unwonted taxes, and heavie subsidies upon the Commons, insomuch, that many of them; to enjoy a barren liberty, forsook their fruitfull inheritance, and with their wives and children as out-lawes, lived in woods, preferring that naked name of freedome, before a sufficient maintenance possest under the thraldome of a Conquerar, who subverted their Lawes, disweaponed the Commons, prevented their night meetings, with a heavie penalty, that every man at the day closing should cover his free, and depart to his rest, thereby depriving them of all opportunity to consult together, how to recover their liberties; collating Officers all both of command and judicature, on those who were his, which made, saith Daniel, page 46. his domination such as has would have it; For whereas the causes of the Kingdome were before determined in every Shire, And by a Law of King Edward Segnier, all matters in question should, upon speciall penalty, without further deferment, be finally decided in the Gemote, or Conventions held monethly in every Hundred: Now he ordained, That four times in the yeare for certain dayes, the same businesse should be determined, in such place as he would appoint, where he constituted Judges, to attend to that purpose; and others from whom as from the bosome of the Prince all litigators should have justice. And to awake them &illegible; miserable, as slaves could be made, He ordered that the Laws should he practised in French, &illegible; Petitions, and businesses of Court &illegible; French, that so the poor miserable people might be gulled, and cheated, undone and destroyed; not onely at his will and pleasure, but also at the will and pleasure of his under Tyrants and Officers; For to speak in the words of Martin, in his History, page 4. He &illegible; and established &illegible; and severe Lawes, and published them in his own language; by meanes whereof, many (who were of great estate, and of much worth) through ignorance did transgresse and their smollest offences were great enough to entitle the CONQVEROR to their lands, to the lands and riches which they did possesse; All which he seized on, and took from them without remorse. And in page 5. he declares, hat he erected sundry Courts, for the administration his new Lawes, and of Justice, and least his Iudges should bear to great a sway by reason of his absence; he caused them all to follow his Court, upon all removes, Whereby he not only curbed their dispensations which &illegible; them to be great, but also tired out the English Nation with extraordinary troubles, and excessive charges, in the prosecution of Suites in Law.

From all which relations we may observe;

First, from how wicked, bloudy, triviall, base, and tyrannicall a Fountain our gratious Soveraignes, and most excellent Majesties of England have sprung; namely; from the Spring of a Bastard, of poore condition, by the Mothers side, and from the pernitious springs of Robbery, Pyracie, violence, and Murder, &c. Howsoever, fabulous Writers, strive (as Daniel saith) to abuse the credulity of after Ages, with Heroicall, or mircaulous beginnings, that surely if it be rightly considered, there will none dote upon those kind of Monsters, Kings; but Knaves, Fooles, Tyrants, or Monopolizers, or unjust wretched persons, that must of necessity have their Prerogative to rule over all their wickednesses.

Secondly, Observe from hence, from what a pure Fountain our inslaving Lawes, Judges, and Practises in Westminster Hall, had their originall; namely, from the will of a Conqueror and Tyrant, for I find no mention in History of such Judges, Westminster Hall Courts, and such French ungodly proceedings as these, untill his dayes, the burthen of which, in many particulars to this day, lies upon us.

But in the 21. of this Tyrants reigne, After that the captivated Natives had made many struglings for their liberties, and he having alwayes suppressed them, and made himself absolute, He began (saith Daniel, fol. 43.) to govern all by the customes of Normandy; whereupon the agrieved Lords, and sad People of England tender their humble Petition, beseeching him in regard of his Oath made at his Coronation; and by the soule of St. Edward, from whom he had the Crown and Kingdome, under whose Lawes they were born and bred, that he would not adde that misery, to deliver them up to be judged by a strange Law which they understood not. And (saith he) so earnestly they wrought, that he was pleased to confirme that by his Charter, which he had twice &illegible; by his Oath. And gave commandment unto his &illegible; to see those Lawes of St. Edward to be inviolably observed throughout the Kingdome. And yet notwithstanding this &illegible; &illegible; the &illegible; afterward granted by Henry the second, and King Iohn, to the same effect; There followed a great Innovation both in Lawes and Government in England; so that this seemes rather to have been done to acquir the people, with a shew of the confirmation of their antient Customes and liberties, then that they enjoyed them in effect: For whereas before, those Lawes they had, were written in their tongue intelligible unto all; Now they are translated into Latine and French. And whereas the Causes of the Kingdome were before determined in every Shire, And by a Law of King Edward senior, all matters in question should upon speciall penalty without further deferment, be finally decided in their Gemote or Conventions held monethly in every Hundred (A MOST GALLANT LAW.) But he set up his Judges four times a yeare, where he thought good to be their Causes; Again, before his Conquest, the inheritances descended not alone, but (after the Germane manner) equally divided to all the children which he also altered; And after this King (alias, Tyrant) had a cruell and troublesome raign, his own Son Robert rebelling against him (yea, saith Speed, fol. 430.) all things degenerated so (in his cruell dayes) that time and domestick fowles, as Hens, Geese, Peacocks, and the like, fled into the Forrests and Woods, and became very wild in imitation of men. But when he was dead, his Favourites would not spend their pains to bury him, and scarce could there be a grave procured to lay him in; See Speed, fol. 434. and Daniel, fol. 50. and Martin, fol. 8.

WILLIAM THE SECOND, to cheat and cosen his eldest brother Robert, of the Crown, granted relaxation of tribute with other releevements of their dolencies, and restored them to the former freedome of hunting in all his Woods and Forrests, Daniel fol. 53. And this was all worth the mentioning, which they got in his dayes.

And then comes his brother, Henry the first, to the Crown, and he also stepping in before Robert the eldest brother, and the first actions of his government tended all to bate the people, and suger their subjection, as his Predecessour upon the like imposition had done, but with more moderation and advisednesse; for he not only pleaseth them in their releevement, but in their passion, by punishing the chiefe Ministers of their exactions, and expelling from his Court all dissolute persons, and eased the people of their Impositions, and restored them to their lights in in the night, &c. but having got his ends effected, just tyrant-like, he stands upon his Prerogative, that is, his will and lust; but being full of turmoiles, as all such men are, his Son the young Prince, the only hope of all the Norman race was at Sea, (with many more great ones) drowned, after which, he is said never to have been seen to laugh, and having (besides this great losse) many troubles abroad, and being desirous to settle the Kingdome upon his daughter Mand the Empresse, then the wife of Goffery Plantagines, in the 15. year of his reign he begins to call a Parliament, being the first after the Conquest: for that (saith Dan. fol. 66.) he would not wrest any thing by an imperiall power from the Kingdome (which might breed Ulcers of dangerous nature) he took a course to obtain their free consents, to observe his occasion in their generall Assemblies of the three Estates of the Land, which he convocated at Salisbury, and yet notwithstanding by his prerogative, resumed the liberty of hunting in his Forrests, which took up much faire ground in England, and he laid great penalties upon those that should kill his Deere. But in this Henry the first, ended the Norman race, till Henry the second: For although Henry the first had in Parliament caused the Lords of this Land, to swear to his Daughter Mand and her Heires, to acknowledge them as the right Inheritors of the Crown: Yet the State elected, and invested in the Crown of England (within 30. dayes aftter the death of Henry) Stephen Earle of Bolloign, and Montague Son of Stephen, Earl of Blois, having no title at all to the Crown, but by meer election was advanced toit, The Choosers being induced to make choice of him, having an opinion that by preferring one, whose title was least, it would make his obligation the more to them, and so, they might stand better secured of their liberties, then under such a one as might presume of a hereditary succession.

And being crowned, and in possession of his Kingdome, hee assembleth a Parliament at Oxford, wherein hee restored to the Clergie all their former liberties, and freed the Laity from their tributes, exactions, or whatsoever grievances oppressed them, confirming the same by his Charter, which faithfully to observe, hee took a publike Oath before all the Assembly, where likewise the BBs. swore fealty to him, but with this condition (saith Daniel, folio 69.) SO LONG AS HE OBSERVED THE TENOVR OF THIS CHARTER, And Speed in his Chronicle, fol. 458. saith, that the Lay-Barons made use also of this policie, (which I say is justice and honesty) as appeareth by Robert Earl of Glocester, who swote to be true Liege-man to the King, AS LONG AS THE KING WOVLD PRESERVE TO HIM HIS DIGNITIES, AND KEEPE ALL COVENANTS: But little quiet the Kingdome had; for rebellions and troubles dayly arose by the friends of Maud the Empresse, who came into England, and his Associates pitching a field with him, where he fought most stoutly, but being there taken, hee was sent prisoner to Bristoll. And after this Victory thus obtained, (saith Martin, fol. 29.) The Empresse, with many honourable tryumphs and solemnities was received into the Cities of Circester, Oxford, Winchester, and London; but the Londoners desiring the restitution of King Edwards Lawes, which she refused, which proved her ruine, and the restitution of King Stephen out of prison, and to the Crown again; and after some fresh bouts, betwixt King Stephen, and Duke Henry (Mauds eldest Son) a Peace was concluded betwixt them in a Parliament at Westminster, and that Duke Henry should enjoy the Crown after King Stephen. At the receiving of which, he took the usuall oath, and being like to have much work in France, &c. being held in thereby from all exorbitant courses, he was therefore wary to observe at first, all meanes to get, and retain the love and good opinion of this Kingdom, by a regular and easie government, and at Waldingford, in Parliament (saith Daniel, fol. 80.) made an act, that both served his own turn, and much eased the stomackes of his people, which was the expulsion of strangers, wherewith the Land was much pestered, but afterwards was more with Becket the traytorly Arch-bishop of Canterbury, And after him succeeds his Son Richard the first. (At the beginning of this mans Reigne, a miserable massacre was of the Jewes in this Kingdom,) who went to the holy wars, and was taken prisone by the Emperour as he came home, of whom (Daniel saith, fol. 126.) that) he reigned 9 years, and 9 moneths, wherein he exacted, and consumed more of this Kingdome, then all his Predecessours from the Norman had done before him, and yet lesse deserved then any. His brother Duke John being then beyond Seas with his Army, was by the then Archbishop of Canterburies meanes endeavoured to be made King, who undertooke for him that he should restore unto them their Rights, and govern the Kingdome as he ought with moderation, and was thereupon,The Kings Oath. (after taking three oathes, which were to love holy Church, and preserve it from all Oppressours, to govern the State in justice, and abolish bad Lawes, not to assume this Royall honour, but with full purpose to rerform: that he had sworn, Speed 534.) crowned King; And because the title was doubtfull, in regard of Arthur the Posthumus Son of Geffery, Duke of Brittain, King Iohns eldest brother (Speed fol. 532) he receives the Crown and Kingdome by way of election, Daniel fol. 127. the Archbishop that crowned him, in his Oration professing, before the whole Assembly of the State, That by all reason, Divine and Humane, none ought to succeed in the Kingdome, but who should bee for the worthinesse of his vertues, universally chosen by the State, as was this man. And yet notwithstanding all this, he assumed power by his will and prerogative, to impose three shillings upon every ploughland, and also exacted great Fines of Offenders in his Forrests. And afterwards summons the Earles and Barons of England to be presently ready with Horse and Arms to passe the Seas with him. But they holding a conference together at Lecester, by a generall consent send him word, That unlesse he would render them their rights and liberties, they would not attend him out of the Kingdome. Which put him into a mighty rage; but yet he went into France, and there took his Nephew Arthur prisoner, and put him to death, by reason of which the Nobility of Britaigne, Anjou and Poictou, took Armes against him, and summon him to answer at the Court of Justice of the King of France, to whom they appeale. Which he refusing, is condemned to lose the Dutchy of Normandy, (which his Ancestors had held 300. yeares) and all other his Provinces in France, which he was accordingly the next yeare deposed of.

And in this disastrous estate (saith Daniel fol. 130.) he returnes into England, and charges the Earles and Barons with the reproaches of his losses in France; and sines them (by his Prerogative) to pay the seventh part of all their goods for refusing his aid. And after this going over into France to wrastle another fall, was forced to a peace for two yeares, and returnes into England for more supplies; where, by his will, lust, and prerogative, he layes an imposition of the thirteenth part of all moveables, and other goods, both of the Clergie and Laitie; who now (saith Daniel) seeing their substances consume, and likely ever to be made liable to the Kings desperate courses, began to cast about for the recovery of their ancient immunities, which upon their former sufferance had been usurped by their late Kings. And hence grew the beginning of a miserable breach between the King & his people, Which (saith he) folio 131.) cost more adoe, and more Noble blood, then all the Warres forraigne had done since the Conquest: For this contention ceased not, though it often had fair intermissions, till the GREAT CHARTER, made to keep the Beame right betwixt SOVERAIGNTY and SUBJECTION, first obtained of this King JOHN, in his 15. and 16. yeares of his yeares of his reigne; and after of his sonne Henry the 3. in the 3. 8. 21. 36. 42. yeares of his reigne (though observed truly of neither) was in the maturity of a judiciall Prince, Edward the first, freely ratified, Anno regni 27. 28. But I am confident, that whosoever seriously and impartially readeth over the lives of King John, and his sonne Henry the third, will judge them Monsters rather then men, Roaring Lions, Ravening Wolves, and salvadge Beares (studying how to destroy and ruine the people) rather then Magistrates to govern the people with justice and equity:Consider, compare, and conclude. For, as for King John; he made nothing to take his Oath, and immediatly to break it (the common practice of Kings) to grant Charters and Freedomes, and when his turn was served, to annihilate them again; and thereby, and by his tyrannicall oppressions, to embroyle the Kingdome in Warres, Blood, and all kind of miseries. In selling and basely delivering up the Kingdome (that was none of his own, but the peoples) as was decreed in the next Parliament (Speed fol. 565. by laying down his CROWN, Scepter, Mantle, Sword and Ring, the Ensignes of his Royalty, at the feet of Randulphus the Popes Agent, delivering up therewithall the Kingdome of England to the Pope. And hearing of the death of Geffery Fitz Peter, one of the Patrons of the people, rejoyced much, and swore by the Feet of God, That now at length he was King and Lord of England, having a freer power to untie himselfe of those knots which his Oath had made to this great man against his will and to break all the Bonds of the late concluded peace with the people; unto which he repented to have ever condescended. And (as Daniel folio 140. saith) to shew the desperate malice this King (and Tyrant) (who rather then not to have an absolute domination over his people to doe what he listed, would be any thing himselfe under any other, that would but support him in his violences.) There is recorded an Ambassage (the most and impious that ever was sent by any Christian Prince) unto Maramumalim the Mover, intituled, The great King of Africa, &c. Wherein he offered to render unto him his Kingdome, and to hold the same by tribute from him, as his Soveraign Lord: to forgoe the Christian faith (which he held vain) and receive that of Mahomet. But leaving him and his people together by the eares (striving with him for their &illegible; and freedomes (as justly they might) which at last brought in the French amongst them to the almost utter ruine and destruction of the whole Kingdome, and at last he was poysoned by a Monk.

It was this King (or Tyrant) that enabled the Citizens of London to make their Annuall choyce of a Mayor and two Seriffes, Martaine 59.

The Kingdome being all in broyles by the French, who were called in to the aid of the Barons against him; and having got footing; plot and endevour utterly to extinguish the English Nation. The States at Glecester in a great Assembly, caused Henry the third his sonne, to be Crowned, who walked in his Fathers steps in subverting the peoples Liberties and Freedomes, who had so freely chosen him, and expelled the French: yet was hee so led and swayed by evill Councellors, putting out the Natives out of all the chief places of the Kingdome, and preferred strangers only in their places. Which doings made many of the Nobility (saith Daniel folio 154.) combine themselves for the defence of the publick according to the law of Nature and Reason) and boldly doe shew the King his error, and ill-advised course in suffering strangers about him, to the disgrace and oppression of his naturall liege people, contrary to their Lawes and Liberties; and that unlesse he would reforme this excesse, whereby his Crown and Kingdome was in imminent danger, they would withdraw themselves from his Councell. Hereupon the King suddenly sends over for whole Legions of Poictonions, and withall summons a Parliament at Oxford, whither the Lords refuse to come. And after this, the Lords were summonedto a Parliament at Westminster, whither likewise they refused to come, unlesse the King would remove the Bishop of Winchester, and the Poictonians from the Court: otherwise by the common Counsell of the Kingdom, they send him expresse word, They would expell him and his evill Councellors out of the land, and deale for the creation of a new King. Fifty and six years this King reigned in a manner in his Fathers steps: for many a bloody battell was fought betwixt him and his people for their Liberties and Freedomes, and his sonne Prince Edward travelled to the warres in Africa: The State after his Fathers death in his absence assembles at the New Temple, and Proclaim him, King. And having been six years absent, in the the third yeare of his reigne comes home, and being full of action in warres, occasioned many and great Levies of money from his people; yet the most of them was given by common consent in Parliament; and having been three years out absent of the Kingdom, he comes home in the 16. year of his reign. And generall complaints being made unto him of ill administration of justice in his absence, And that his Judges like so many Jewes, had eaten his people to the bones, & ruinated them with delays in their suits, and enriched themselves with wicked corruption (too comon a practice amongst that generation) he put all those from their Offices who were found guilty (and those were almost all) and punished them otherwise in a grievous manner, being first in open Parliament convicted. See Speed folio 635. And, saith Daniel, folio 189. The fines which these wicked corrupt Judges brought into the Kings Coffers, were above one hundred thousand marks; which at the rate (as money goes now) amounts to above three hundred thousand Markes; by meanes of which he fillled his empty coffers, which was no small cause that made him fall upon them. In the mean time these were true branches of so corrupt a root as they flowed from, namely the Norman Tyrant. And in the 25. yeare of his reigne he calles a Parliament, without admission of any Church-man: he requires certain of the great Lords to goe into the warres of Gascoyne; but they all making their excuses every man for himselfe: The King in great anger threatned that they should either goe, or he would give their Lands to those that should.

Whereupon Humphry Bohun, Earle of Hereford, High Constable, and Roger Bigod, Earle of Norfolk, Marshall of England, made their Declaration, That if the King went in person, they would attend him, otherwise not. Which answer more offends. And being urged again, the Earle Marshall protested, He would willingly go thither with the King, and march before him, in the Vantguard, as by his right of inheritance he ought to doe. But the King told him plainly, he should goe with any other, although himself went not in person. I am not so bound (said the Earle) neither will I take that journey without you. The King swore by God, Sir Earle you shall goe or hang. And I sweare by the same oath, I will neither goe nor hang (said the Earle). And so without leave departed.

Shortly after the two Earles assembled many Noblemen, and others their friends, to the number of thirty Baronets; so that they were fifteen hundred men at Arms, well appointed, and stood upon their own guard: The King having at that time many Irons in the fire of very great consequence, judged it not fit to meddle with them, but prepares to go beyond the Seas, and oppose the King of France; and being ready to take ship, the Archbishops, Bishops, Earles, and Barons, and the Commons send him in a Roll of the generall grievances of his Subjects, concerning his Taxes, Subsidies, and other Impositions, with his seeking to force their services by unlawfull courses, &c. The King sends answer, that he could not alter any thing without the advice of his Councell, which were not now with them; and therefore required them, seeing they would not attend him in this journey (which they absolutely refused to doe, though he went in person, unlesse he had gone into France or Scotland) that they would yet do nothing in his absence prejudiciall to the peace of the Kingdom. And that upon his return, he would set all things in good order as should be fit.

And although he sayled away with 500. sayle of ships, and 18000. men at Armes, yet he was crossed in his undertakings, which forced him (as Daniel saith) to send over foremore supply of treasure, and gave order for a Parliament to be held at York by the Prince, and such as had the managing of the State in his absence; wherein, for that he would not be disappointed, he condescends to all such Articles as were demanded concerning the Great Charter, promising from thence-forth never to charge his Subjects, otherwise then by their consents in Parliament, &c. which at large you may reade in the Book of Statutes, for which, the Commons of the Realm granted him the ninth peny: At so deer a rate were they forced to buy their own Rights, at the hands of him that was their servant, and had received his Crown and Dignity from them, and for them: But the People of England not being content with the confirmation of their Liberties, by his Deputies, presse him (at a &illegible; at Westminster) the next year to the confirmation of their Charters, he pressing hard to have the Clause, Salvo Jure Coroæ nostiæ put in, but the ‘People would not endure it should be so: Yet with much adoe he confirmes them, according to their mind, and that neither he, nor his heires, shall procure, or do any thing whereby the Liberties of the Great Charter contained, shall be infringed or broken; and if any thing be procured, by any person, contrary to the premises, i shall be held of no force, nor effect, And this cost them dear, as I said before.