Liberty Matters

A Seat at the Table, but Only One

I am a great admirer of the novels of Jane Austen. The acerbic wit, the trenchant social observations, the focus on the importance of character formation and self-understanding as the basis for a good marriage, the unparalleled prose…I love it all. I love the films. The parodies. The web series. The “inspired by” novels. I have paper dolls of Jane Austen characters prominently displayed on the wall of my office. I am a fan.

But I am tired of hearing about Jane Austen.

It is not Austen’s fault. She remains one of my favorite authors. But I am so very tired of the way Austen is turned to, so consistently, as the “woman writer” one includes when looking for a little diversity. In a syllabus, in a set of book recommendations, or in a list of favorite authors, Austen is, too often, a banner brandished to prove the speaker is not, in fact, ignoring women.

It’s weirdly reminiscent of Tom Stoppard’s joke in Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead about a disreputable theater troupe’s performance of “The Rape of the Sabine Women…or rather woman…or rather Alfred.” We value contributions to the history and literature of the liberty movement by women…or rather woman…or rather Austen.

Women fought for a seat at the table of liberty for a long time, but it often feels as if that’s exactly what we got: One seat. And Austen is in it.

It’s not as bleak as I claim, of course. Sometimes, the chair is occupied by Ayn Rand or Mary Wollstonecraft. Sometimes Harriet Taylor (though generally accompanied by sneering). Americanists make space for Abigail Adams, or Sojourner Truth, or one or another of the suffragists. There’s usually a particular woman who is turned to as “the female voice” of a particular topic, time, or place.

But the point is that almost 30 years ago, when I entered graduate school, my cohort and I were all aggravated by precisely this same problem. And we had high hopes that the amazing scholarship being done in women’s history and the great recovery of women’s texts being done would address this. We looked forward to seeing a wider range of women’s works and voices represented in the canon. Maybe we’d even see the end of a need for Women’s History Month and Women’s Studies departments. Women and their works would be so integrated into the fabric of our thought that leaving them out of the great discussions from their historical periods would be as unimaginable as leaving George Washington and Thomas Jefferson out of the history of America’s founding, or leaving Dickens and Shakespeare out of the history of English literature.

I took it as a sign of great hope when Austen’s work crossed over from the English department. She was embraced by economists and philosophers and others--particularly those with an interest in liberty. Austen had opened the door. Surely, the rest would rush in behind her. We had to be on the brink of a renaissance. Work on women’s history and women’s literature could cease being an endless project of recovering forgotten texts and figures and could begin the work of integrating those figures into important, on-going discussions.

But it’s 2022 now, and I’m tired of hearing about Jane Austen.

It’s not, I think, a question of tokenism. Austen’s work is deeply invested in many things that we classical liberals are invested in--questions of virtue and character, questions of economic well-being, of human flourishing, of what makes a civil society, and so on. Austen nearly always has something pertinent to say and we should freely turn to her work when looking for a contribution to these conversations from a smart and capable woman. But there’s something wrong with finding Austen and going no further.

All of this is a somewhat roundabout way of saying that, despite the 1980s feel of Women’s History Month, and despite my younger self’s hope that we’d no longer need it in the future, I think Women’s History Month is perhaps more important than ever because we don’t have any excuses now.

In the mid 90s, when I entered graduate school, before I had a Facebook account, before my first book purchase on Amazon, all the texts in my class on Early Modern Women’s Poetry were Xeroxed print-outs the professor downloaded from the Brown Women Writers Project. (now hosted at Northeastern University) Some of those texts remain remarkably obscure--an anonymous poetry collection titled Eliza’s Babes, for example. Others are now widely available: works by Margaret Cavendish, Aemelia Lanyer, Mary Wroth, and others can now simply be purchased online, rather than ferreted out from obscure corners of the university library stacks. For $19, you can now have a scholarly edition of all of Elizabeth I’s collected works on your Kindle instantly. Texts from BIPOC women, non-Christian women, non-English speaking women, Queer and Trans women, women from a whole range of cultures, standpoints, and communities, are more available to us every day. The work of recovering lost texts and lost voices is endless, of course, and it is an ongoing honor and responsibility.

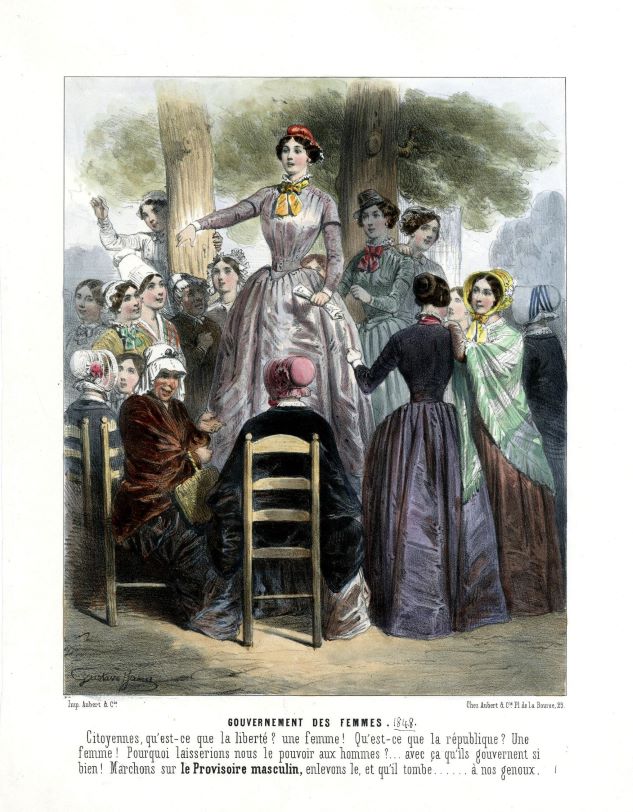

But it is not enough to recover other voices if we recur, over and over again, to the same few. Our ongoing discussions of liberty would surely benefit from the important and interesting contributions that we are now able to access so easily. Work done in the Renaissance and Reformation period that I know best emphasizes how, in those centuries between 1500 and 1800, while women lacked full legal control of their money, their bodies, their educations, and their work they were simultaneously becoming increasingly literate and literary. Early modern women exploded into print, desperate to speak to their contemporaries and to leave a record for the future about what it is like to be denied so many liberties, yet to find ways to grab at them with both hands.

Though I am less familiar with work done outside that period and outside of the English language, we know that this holds. One of the first things that happens as the unfree find ways to educate themselves is that they write, and they speak. And they speak, it is important to add, not just about “gendered” or “minority” concerns and issues. They speak about economics. And law. And war. And peace. And God. And freedom.

It is time to stop collecting lists of names of women who--we seem permanently surprised to discover--thought deeply about their world and wrote those thoughts down. It is time to stop leaning so heavily on a few women whose work is familiar to us, or made comfortable to us by long use, consistent discussion, and elegant presentation in gilded volumes. It is time to read the women who came before Jane Austen, the women Austen read, and the ones she mocked, and the ones who responded to her.

So much work has been done recovering so many of these voices. We need to drag them into the room, invited or not. We need to slam an extra leaf or two into the table. We need to think less about whether the women we bring into the discussion of liberty are voices that people already believe to be important. We need to start insisting on the importance of the voices that we know exist, that scholars have labored to bring to light, but that are not, yet, invited to the table when the talk turns to liberty.

Because it is 2022. And I love Jane Austen. But I am tired of hearing about her.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.