Liberty Matters

Black History Beyond Borders: Heroines in Canadian History

Black History Month inspires us to read about the lives and work of well-known figures in the history of Black liberation. We justifiably turn to the writing of Frederick Douglass, James Baldwin, and Sojourner Truth to better understand being Black in America. We read about how and why Thomas Clarkson, Adam Smith, and William Wilberforce made early, important, and ultimately successful arguments against the African slave trade. But as we all know, Black history extends beyond its best-known figures and beyond the borders of the United States.

In celebration of Black History Month, we’d like to shine a light on three women who played important roles in the end of slavery and the advancement of civil rights in Canada. Their contributions illustrate how the actions of individuals shape history, the parallel experiences of Black Canadians and Black Americans, and the complex problems they both faced following abolition.

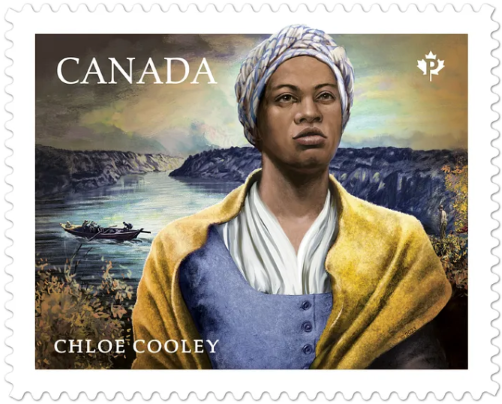

Chloe Cooley

Chloe Cooley was a Black slave from Upper Canada who attempted escape from her American Loyalist enslaver, a white farmer named William Vrooman who fled to Canada following the American Revolution.

Although the British Crown under King George III explicitly allowed Loyalists to bring enslaved workers into Canada, it had also granted citizenship and meagre land to Black Loyalists. Vrooman and other slaveholders worried that protection for Black Loyalists signified that the legal environment in Canada would eventually force them to free the people they enslaved. Rather than risk losing his “property,” Vrooman sold Cooley to a man in the United States, where laws were being passed to strengthen the institution of slavery.

Cooley had a history of fighting her bondage. She regularly protested by behaving in an “unruly manner”: stealing property that belonged to Vrooman, resisting her work assignments, and leaving Vrooman’s property until she decided it was time to return.

So when Vrooman tried to sell her back into the United States, Cooley refused to act as complacent property. She boldly resisted: kicking, screaming, and shouting to be let go while many looked on. It took Vrooman and two other men to restrain Cooley. They severely beat her, tied her up, and forced her into a boat before Vrooman could complete the sale. But this time, her resistance drove the first stakes in the Underground Railroad.

Cooley’s brutal treatment caught the attention of Peter Martin, a Black Loyalist who witnessed her abduction. He brought a white man who had also witnessed the seizure of Chloe Cooley to the Executive Council of Upper Canada to report what he saw. Among those who heard this report was Upper Canada Lieutenant Governor John Graves Simcoe.

Simcoe’s anger when he heard about this incident inspired him to present a bill that would prohibit slavery outright. Unfortunately, 12 of the 25-person government owned slaves and the bill was doomed—but it was the catalyst for the Act Against Slavery.

In 1793, Simcoe introduced the Act Against Slavery, and its declaration that all new slaves who entered Canada would become free paved the way for thousands of American slaves to escape to Canada. This legislation made it illegal for any new slaves to be brought into Canada and freed the children of slaves when they turned 25. However, it did not forbid the sale of enslaved people within Upper Canada or across the border into the United States—passed earlier, it would not have saved Cooley.

Although Chloe Cooley was never heard of again after being sold by Vrooman, her legacy of resistance helped bring about freedom for countless others. As imperfect as the Act Against Slavery was, the legal difference it introduced to the border between the United States and Canada would prove to be one of the most important in the history of the two countries.

Mary-Ann Shadd

Mary-Ann Shadd was an American-Canadian activist whose work spanned both sides of the border. Shadd was born free in Delaware, a slave state, to abolitionist parents who ran a station of the Underground Railroad. Shadd’s parents moved her to Pennsylvania so that she and her siblings could be educated. When the second Fugitive Slave Act passed in 1850, even free Black Americans were in danger of being kidnapped and sold into slavery, so the Shadds moved to Canada where their freedom would be secure.

Shadd, a teacher, moved to Sandwich in Canada West (now part of Windsor, Ontario) and opened an integrated school to meet the need for education of emancipated Black children from the United States. From there, her abolitionist activism only grew. In 1852 she published A Plea for Emigration; or Notes of Canada West, a pamphlet urging Black Americans to move to Canada where they could be free.

In 1853, Shadd began publication of The Provincial Freeman, Canada’s first antislavery newspaper, which also made her the first Black woman in North America to establish and edit a newspaper and one of the earliest women to start a newspaper in Canada. Her newspaper fought against the popular presentation of Black people as poor and downtrodden, in need of charity. The Provincial Freeman also provided an important platform for Black Canadian activists.

Shadd believed what Black people on both sides of the border needed was freedom. Most refugees from American slavery were, after all, able to quickly establish themselves and become self-sufficient after reaching Canada. She believed self-reliance was key, and encouraged Black Canadians to insist on equal treatment and even to take legal action to obtain it if required. Shadd was also instrumental in forming the abolitionist group The Provincial Union, which was run for and by the Black community.

In spite of the dangerous legal environment for free Black people, Shadd continued to return to the United States to promote The Provincial Freeman and to work as a speaker and activist. She sat as a delegate at the 1855 Philadelphia Colored Convention. As a woman, she had to fight for her spot, never having been allowed to attend before. Her advocacy for emigration also made her a controversial figure with other delegates.

After the death of her husband and during the U.S. Civil War, Shadd left her job as a teacher in Chatham, Ontario, to return to the United States and work as a recruiter for the Union Army in Indiana. After the Union victory, Shadd moved to Washington D.C. to work as a teacher and to attend Howard University, becoming one of the first Black women to attain a law degree in the United States.

Shadd’s activism helped to support the efforts that both immigration and the insistence on equal rights would play in the history of Black Canadians. Her work was important on both sides of the border, and illustrates the role that different legal environments and immigration can play in the fight for equal rights.

Viola Desmond

Viola Desmond has finally gained prominence as the first Canadian woman to appear on a bank note, but when she was chosen many were left wondering who she was. Although she’s sometimes called “Canada’s Rosa Parks”, Viola Desmond refused to give up her seat in the white section of a movie theatre in New Glasgow, Nova Scotia nine years before Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat in the white section of an Alabama bus.

Desmond was a businesswoman who took advantage of the fact that many beauty schools in the early 20th century refused to take Black students. After receiving her education in Montréal, Atlantic City, and New York, she returned to Nova Scotia to open a beauty salon that could cater to Black clients in Halifax. She also opened the Desmond School of Beauty Culture to educate other Black beauticians, providing them with the skills to open their own businesses and employ other Black women in their communities. She also established a line of beauty products.

Although her business carved out a place for entrepreneurial and independent Black women in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Québec when discrimination and segregation were still rampant, Viola Desmond is most often remembered for her legal battle over a movie ticket. Stuck in New Glasgow on a business trip, she decided to go to the movies. She tried to buy a more expensive main floor seat, but the theatre refused to sell her anything but a ticket for the cheaper balcony seats because she was Black. Desmond persisted, taking a seat on the main level, where the manager first told her to leave and then dragged her from the theatre when she refused. The manager had her arrested and charged with tax evasion for failing to pay the one-cent difference in tax between the floor and balcony tickets—a reminder that although Canada did not have legal segregation or explicitly racist laws, the government continued to find ways to participate in and enable discrimination against people of colour.

Although Viola Desmond was convicted and fined and her legal fight did not result in a change in the law, her aggressive defence of her dignity was an example to the Black community in Nova Scotia in the fight for equal rights. Equally aggressive was Nova Scotia’s pushback. Desmond’s appeal went all the way to the provincial Supreme Court. This fight, which she ultimately lost, led to her leaving Nova Scotia for Montréal and eventually New York City, where she died in 1965.

Like Chloe Cooley, it was not dedication to activism nor some ultimate heroic victory that made Viola Desmond an inspiration for future change. It was her willingness to push back when she was treated as less than a person of equal worth. Comparing Desmond’s case to Cooley’s illustrates both how far Canadians had come in 150 years and how far they still had to go. It wasn’t until 2010 that Desmond was posthumously pardoned by the Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia. Her story spread more rapidly, along with a more frank discussion of Canada’s history of segregation and racism, when she was selected to appear on the $10 note beginning in 2018.

----

The struggles and achievements of exceptional Black Canadian women like Chloe Cooley, Mary Ann Shadd, and Viola Desmond, who fought for emancipation, equal rights, and equal dignity, should continue to inspire those still fighting for equality and rights for Black people.

While the stories of Cooley, Shadd, and Desmond are exceptional, they also illustrate the role that individuals willing to take a stand for their personhood, their dignity, and the dignity of others play in shaping the overall history of any group. Black History Month gives us an opportunity to reflect on the incredible work of Black women in the struggle for the equal recognition of human liberty. They are a testament to the importance of ensuring that all people are free to contribute to our society and our world.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.