Liberty Matters

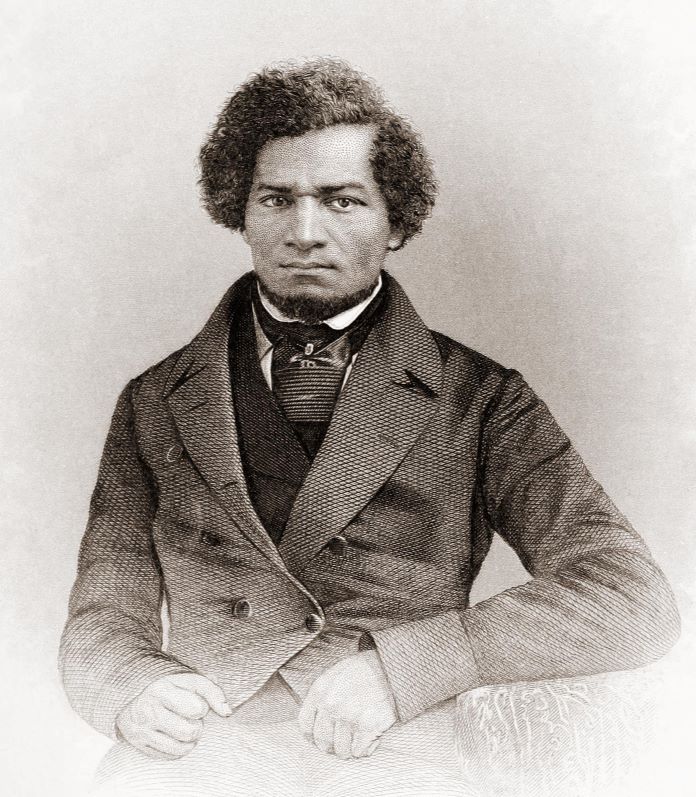

Frederick Douglass and the Black Christian Experience

Frederick Douglass is most well-known for the autobiography in which he describes his escape from slavery, and for his lifetime of abolitionist efforts. His scathing account of hypocritical and cruel white Christian slaveholders led many of his readers to assume that his experiences had soured him on the faith. To correct these misconceptions, Douglass published an appendix that has now become famous, distinguishing between “the slaveholding religion”and “Christianity proper.” He refused to call “the religion of this land Christianity” but rather saw the application of that title to the white Christians he had met as “the climax of all misnomers, the boldest of all frauds, and the grossest of all libels.”

Ten years later, Douglass published a second autobiography in which he chronicled his conversion as a teenage boy and his discipleship under his beloved friend and fellow slave, Mr. Lawson. He contrasts the teachings of Mr. Lawson, who prayed with confidence for Frederick’s liberty, and the religion of the white pastor who often came to instruct his mistress. His master threatened violence to keep Frederick away from Lawson.

Douglass’s account is notable partially for being quite typical of the Black Christian experience under slavery as described in the classic Slave Religion by Albert Raboteau: 1) an intense conversion experience through interaction with other enslaved Christians, 2) formation in the faith in secret meetings separate from whites, 3) theology with a heavy emphasis on the doctrine of creation in the image of God, the Exodus story, and prophetic calls to cease oppression throughout the Hebrew scriptures, and 4) persecution by slave-holders for religious activity such as prayer and meeting attendance. In fact, Black Christianity in America only began developing in earnest after the Great Awakenings because white slaveholders purposefully avoided sharing the faith with slaves. They feared that the unavoidable scriptural doctrine of the equality of believers would necessitate legal freedom for slaves.

A Kingdom that Comes Not by Power, but Love

The Black American experience of faith can seem odd if we think of the formerly enslaved as embracing the ‘white man’s religion’ of their masters. This becomes particularly poignant when Black Americans embrace the love of enemies and the way of non-violence laid out in the Sermon on the Mount. Thus, the legacy of serious Christians whose faith informed their fight for civil rights – people like Fannie Lou Hamer and Martin Luther King, Jr. – has been labeled by some as ‘accommodationism’ and a sell-out to white respectability politics.

This understanding of the Black Church could not be further from the truth. Not only did both its practices and doctrines develop independently from that of white slaveholders, but whites’ unwillingness to worship together with Blacks created a realm of freedom and empowerment in the Black church that made it the undisputed hub of Black cultural life. Black Christians affirmed the imago dei of Genesis 1: the equal and infinite dignity and value of every human being based on their creation by a loving God. They read Isaiah, Ezekiel, Amos, and others as making a righteous case against their own nation for mistreating or ignoring the needs of those vulnerable to oppression such as widows, orphans, the poor, and strangers. They embraced Jesus’s upside-down kingdom, which proceeds not on power, but on love.

As James Baldwin observed, Martin Luther King, Jr. did not advocate planned non-violent action to appease whites. Rather, King’s “philosophy of love for the oppressor is a genuine aspect of his being.” The Black church is neither progressive nor conservative, politically speaking. It resides in a category of its own, proceeding on the logic of another kingdom altogether.

The Black Struggle and the Black Church

Frederick Douglass went on to become a licensed preacher in the African Methodist Episcopalian Zion church from whose basement he published The North Star. Douglass’s consistent takedowns of Christian practice in white America ought to be read not as an outsider’s condemnations but as the fiery passion of a prophet defending the true faith against heresy. While he was frustrated with the meekness of some Black Christians of his day, his prophetic spirit animated the movements for Black education, economic power, and political freedom that spun out of the Black church.

Douglass didn’t much trust whites to undo past wrongs effectively. Instead, he insisted that “[a]s colored men, we only ask to be allowed to do with ourselves, subject only to the same great laws for the welfare of human society which apply to other men…. Let us stand upon our own legs, work with our own hands, and eat bread in the sweat of our own brows.” Grievously, it would take several more generations for Black Americans to enjoy the benefits of the rule of law. They were falsely convicted of crimes and leased out to factories; subject to terrorism by their own neighbors; excluded from labor unions; their property was taken for highways, and their homes were declared uninsurable by the government.

Douglass didn’t need to have faith in whites. His faith in God and in the untapped potential of his Black brothers and sisters was proved true through so many efforts that blossomed from the Black church.

Mary Peake’s educational efforts in Virginia led to the highest levels of Black property-ownership in the country. It was Mary’s deep faith that led her to her clandestine classroom where she taught slaves and free Blacks to read. By the time she died, the American Missionary Association had teamed up with her and would go on to officially found the Hampton Institute.

Booker T. Washington, who recommended reading the Bible every day, attended Hampton and founded Tuskegee. These institutes sent thousands of teachers out to educate young Black minds, and his National Negro Business League created an impressive network of Black entrepreneurs.

Following in the footsteps of Douglass’s passion for the written word, an astonishing explosion of Black literacy may be among the greatest in history in terms of its sheer speed and reach: in 1870 20% of Black Americans could read, but by 1930 85% could. As has been the case for much of the literacy movement around the world, the desire of Black Americans aligned with the radical Reformation idea that everyone should be able to read the Bible.

Douglass once said that America’s problem was not the Constitution, which he called “a great liberty document” but whether we would live up to our Constitution. With a like mind, the NAACP, whose leaders were often ministers and heads of Black denominations, fought for decades to make the law acknowledge Black rights. In the same vein, Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. called the founding documents of the United States a “blank check” of freedom which Black Americans were finally taking to the bank.

Douglass never lost his faith. Just a few years before his death, he laid his hope for our country on the “broad foundation laid by the Bible itself, that God has made of one blood all nations of men to dwell on all the face of the earth.” The Black church has remained faithful to this healing vision for the United States for over two centuries, in the face of crushing injustice and discouragement. The Black church is a philosophically rich, culturally anchored, and historically central institution of American civil society that deserves widespread historical and cultural acknowledgement for its pivotal role in the life of this nation.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.