Liberty Matters

Sources, Appearances, and Legacy

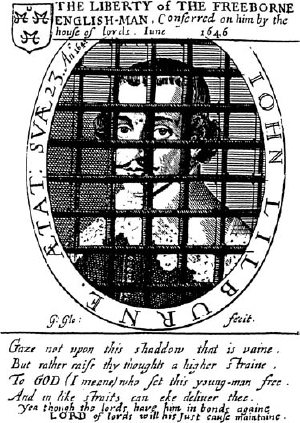

I am very grateful and honored to have three responses from scholars who among them have made such a contribution to our understanding of the Levellers and their place in history. Reading their responses, I see three clear issues or classes of question. These are (not surprisingly) the ones that dominate the historiography, particularly the more recent accounts: 1) the sources or origins of the ideal later developed by the Leveller movement (and indeed by parliamentarian radicals more generally); 2) the way these ideas mutated and developed under the pressure of events and the transformation of political culture in the 1640s, along with the nature of the ideas that emerged from that process and the implications of them for political theory; and 3) the nature of the legacy and transmission of those ideas (if there was any) together with the place they have in subsequent historiography.

I am very grateful and honored to have three responses from scholars who among them have made such a contribution to our understanding of the Levellers and their place in history. Reading their responses, I see three clear issues or classes of question. These are (not surprisingly) the ones that dominate the historiography, particularly the more recent accounts: 1) the sources or origins of the ideal later developed by the Leveller movement (and indeed by parliamentarian radicals more generally); 2) the way these ideas mutated and developed under the pressure of events and the transformation of political culture in the 1640s, along with the nature of the ideas that emerged from that process and the implications of them for political theory; and 3) the nature of the legacy and transmission of those ideas (if there was any) together with the place they have in subsequent historiography.Regarding the first of these, David Wootton and Iain Hampsher-Monk both make a similar point: that we should see Leveller ideas (and also the activism they both grew from and led to) as having explicitly religious roots. Specifically, they both argue that foundational Leveller ideas grew out of radical Protestant (or more narrowly, Puritan) thought. Hampsher-Monk argues that this is true not only for obvious candidates such as the idea of religious liberty, but also for political ideas such as popular sovereignty because of the way the religious beliefs were prior to others and determinative of them in important ways. I think this is undoubtedly true, and in particular I agree with the argument that the idea of a fundamental law was increasingly seen in religious rather than historical terms, with important consequences for their understanding of things like law and autonomy.

I disagree, though, that ecclesiology was not so important — here I find myself agreeing with J. C. D. Clark in fact. This also relates to the argument Wootton makes: that the idea of a re-founding of a wrecked ship of state or political order derives from Puritan thought. In radical Protestant thinking, the whole Reformation could be seen in those terms, as a relaunching and reconstitution of the Church (as opposed to the more limited model of refurbishment found in divines such as Hooker).

Moreover, what the Levellers and many other radicals clearly and explicitly advocated was a radically voluntarist ecclesiology in which congregations were gatherings of individual seekers who came together and formed a self-governing collective that regulated its own affairs and governed their pastor on a continuing basis, with the option of dissolving or dividing. This bottom-up voluntarist vision was clearly in conflict with the idea of an established order with top-down authority, whether Episcopalian or Presbyterian. In this the Levellers were indeed part of a wider movement that included people such as Milton, Goodwin, and many figures in both the Rump and the New Model Army.

This obviously bears on the points made by both Hampsher-Monk and Rachel Foxley about the way the ideas came together and transformed the nature and implications of the ideas and proposals that resulted. I agree completely with Foxley that the 1640s saw a whole range of developments that produced a new kind of political culture and with it novel kinds of both activism and debate — and consequently ideas — that fed into and influenced both of those. This reflected simply the collapse of elite authority produced by the crisis, particularly in London but also in parts of the provinces. This is a definitive feature of revolutionary episodes (as opposed to simple uprisings or rebellions, no matter how large) and is, I think, best captured by Perez Zagorin's category of "revolutionary civil wars." Foxley and Wootton both refer to the idea of the re-founding of political order in the context of a political crisis that was seen to have dissolved the existing order. As Foxley notes, this is not classical state-of-nature theory because the new idea of representation that emerged in the mid-1640s meant that the state of nature was a continuing state of affairs that existed either all the time or at regular intervals (although we can see in their proposals that the Levellers were grappling with the implications of this position).

It is this idea of popular sovereignty and the nature of political representation that is the truly radical, even subversive part of Leveller thinking, and it remains so today. Hampsher-Monk and Foxley both emphasize this and stress what I would also see as the critical feature of the Levellers' thinking. Hampsher-Monk comments that if the natural law, because of its theological basis, has a deontological quality, then the whole idea of popular sovereignty becomes problematic and difficult for any political order. As Foxley puts it, "[P]opular sovereignty … will always, if taken seriously, pose a threat to the legitimacy of the institutions which try to channel it." The reason for both of them is that for the Levellers, popular sovereignty was not the sovereignty of an organic entity or collective: it was individuals, guided by the inner light of conscience, who were sovereign and then came together to reform a political settlement and delegate authority to a "representative" (interestingly not termed a legislature or parliament) that remained, however, continuously subject and responsible to the sovereign individuals whom it represented.

This radical individualism might seem to logically entail anarchism or the kind of idea, later espoused by Thomas Jefferson, of a contingent and temporary constitution that had to be renewed every generation. However, as Foxley notes, it actually did not generate such radical individualist conclusions for thethe Levellers. Instead, there was an idea of a nation or people (the people of England) that was in a very real sense pre-political and natural. Was this a case of simply assuming something and not subjecting it to interrogation, or was it a case of seeing much of social life as pre- or non political? What it did produce was an effort in various programmatic publications to devise a political settlement that could be subscribed to in such a way as to replace the shipwrecked old order, but which would then be locked down against future amendment. The logic of their own position, though, was that ultimate permanence was impossible, so this can be seen as an argument for a settlement that could be completely replaced but not amended, making future change a matter of all or nothing.

Hampsher-Monk and Foxley both comment also on the other striking feature of Leveller constitutional thinking: the emphasis on the limited scope of the powers delegated by sovereign individuals. They both agree that the powers are limited by rules or principles. For Hampsher-Monk these are theological or natural-law ones. (It is not clear if these are two distinct things for him.) For Foxley the matters excluded are ones where individuals were not sovereign in the first place and so had no power to delegate. This seems for her to be based on a "reasonable person" principle inasmuch as reasonable persons, who would not torture themselves and bind their ow consciences, could not possibly delegate that power to someone else. This reveals the extent of their individualism because it begs the question of whether people who were not prepared to do something to themselves would still willingly allow someone else to have that power on the grounds that they did not trust themselves in some way. Moreover, it implies that there is no general good distinct from the good of all individuals (assuming a basic commonality of human nature), so this rejects political collectivism. I would accept this argument but add that the limits also reflected the position that if some kind of restriction or act was wrong for one individual to exercise against another, they could not then delegate a power to do this to a third party, again a strongly individualist position.

The third question concerns how Leveller ideas were transmitted, if at all, and how historians have treated them. Wootton makes the point forcefully that it was very difficult for anyone to access their writings after 1660 because of their plebeian nature and origins. Speculation of their being transmitted orally or through a hidden tradition is just that — speculation. However, he does mention the admittedly exceptional case of Catherine Macaulay, which shows that the ideas were not completely inaccessible: her case actually suggests that they were partly recovered with the "birth of radicalism" at the end of the 18th century.

All three of my interlocutors mention the way the Levellers have been claimed as ancestors and appropriated by people from a range of political traditions — from liberal in the case of Haller and Woodhouse to radical socialist. Foxley makes the important point that none of these claims works fully and everyone who has undertaken this exercise has had to ignore some parts of what the Levellers thought. This, however, is not unusual. Political philosophers and ideologues are constantly looking to appropriate past figures, and in doing so typically gloss over the aspects of their thought that do not fit a writer's own agenda or understanding. John Locke is an example of this, I would argue, and 19th-century feminism is another classic case. The Levellers are not unusual in this.

This leads us to ask: do they still have something to say and challenges to pose? I think they do precisely because they raised such profound and subversive questions about the nature of political authority and representation. They were definitely not anarchists and saw government as necessary and beneficent if properly founded, but they derived it from a body of analysis that made political power contingent and part of a continuing and permanent conversation. In that context it is worth remembering that one of their key demands — for annual parliaments — is the one point of the Charter that has still not been realized.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.