Liberty Matters

Resilient Radicalism: The Levellers and Popular Sovereignty

Ancestry, of course, is a game to which the ancestors themselves are oblivious, played by hopeful heirs searching for their inheritances – financial, cultural, or intellectual as the case may be. To see the Levellers feted 350 years on by both libertarians and socialists is thus no surprise: far stranger things have happened to texts and ideas than that, and Steve Davies's article neatly picks out the elements which both have gleaned from their readings of the Levellers' thought. But it is worth noting that the Levellers have failed to satisfy both camps, as well. Christopher Hill attempted to redeem some Levellers by distinguishing more constitutional Levellers from those with a more economic focus (Hill 1972). As Hill himself noted, the Levellers have inspired the loyalty of those who sought a more middle-of-the-road politics too – as well as socialists and libertarians;, they have been "'social democrats"' or "C'christian democrats"' for those who perhaps found in 17seventeenth-century radicalism a programme which, when imported into the later centuries where it belonged, was merely good, moderate, common sense.

Ancestry, of course, is a game to which the ancestors themselves are oblivious, played by hopeful heirs searching for their inheritances – financial, cultural, or intellectual as the case may be. To see the Levellers feted 350 years on by both libertarians and socialists is thus no surprise: far stranger things have happened to texts and ideas than that, and Steve Davies's article neatly picks out the elements which both have gleaned from their readings of the Levellers' thought. But it is worth noting that the Levellers have failed to satisfy both camps, as well. Christopher Hill attempted to redeem some Levellers by distinguishing more constitutional Levellers from those with a more economic focus (Hill 1972). As Hill himself noted, the Levellers have inspired the loyalty of those who sought a more middle-of-the-road politics too – as well as socialists and libertarians;, they have been "'social democrats"' or "C'christian democrats"' for those who perhaps found in 17seventeenth-century radicalism a programme which, when imported into the later centuries where it belonged, was merely good, moderate, common sense.Davies is right to find a more resilient radicalism in the Levellers than that. The questions raised by Leveller texts are still disturbing, because popular sovereignty – the key political idea to which the Levellers tried, in a succession of proposals, to fit institutional scaffolding – will always, if taken seriously, pose a threat to the legitimacy of the institutions which try to channel it. The Levellers themselves wrestled with this, alternately urging their followers to exercise the kind of genuine popular sovereignty which would break through the bounds of existing political institutions, and proposing new constitutional and institutional solutions which needed to be ratified by and constantly responsive to the people, but which were also to be locked down to prevent future constitutional change.

Part of the urgency and radicalism of the Levellers' vision emerged out of the lived experience of politics during the civil wars. I'm sure it's right to argue that a coherent set of Leveller ideas was developed not in the abstract but under the pressure of events, which were a catalyst for the creative development and fusion of existing ideas. Indeed, some of the less coherent or consistent elements in Leveller thought can be seen as the result of varying rhetorical contexts and pressures (e.g., on the Norman Yoke, discussed by Dzelzainis 2005). These pressures were certainly responsible for one key development which was central to Leveller thought: their revolutionizsed account of representation, which argued that parliament's representation of the people entailed being accountable to the people (Foxley 2013, 64-72). Because this developed under pressure of circumstance, it developed among various radical voices, not only the (future) Levellers. This picture of a richer and more complex set of radical networks at the most committed end of the parliamentarian spectrum as a matrix within which radical religious and (connectedly) political views emerged, and of which the (future) Levellers formed part, has been developed in recent scholarship, particularly the groundbreaking recent book by David Como (2018).

It was not just the events of the 1640s – the threat of the desired parliamentarian victory bringing a renewed form of religious "'persecution"' (as the Levellers saw it: Overton 1645) and the parliament itself becoming a new oppressor – which contributed to the development of the Levellers' thought. The developing political culture of the 1640s — in which popular action played decisive roles in events such as the execution of the Earl of Strafford (with the ebullient participation of the future Leveller leader John Lilburne: Rees 2016, 35);, Londoners threw themselves into the parliamentarian war effort, and radicals particularly so (De Krey 2018, 29-31);, the culture of news was transformed by the proliferation of printed pamphlets and the invention of newsbooks (Raymond 1996);, mass petitioning became a core political tactic (Zaret 2000):, and the Long Parliament itself mobilizsed the public in ways which it could not always control – this developing political culture enabled Leveller politics, but also fed into Leveller thought. Richard Overton, a future Leveller leader, was involved in secret printing operations (Como 2018) and the Levellers used print in a highly purposeful way to engage and educate a sympathetic public. In this context of public involvement in politics and the education of a reading public through parliamentarian and radical print, it is not surprising that advocates emerged for the view that this informed public involvement in politics was not a mere emergency measure, but essential to the normal functioning of a reformed constitution. Popular sovereignty surely became more tangible, and less theoretical, when popular activism was an everyday reality.

Popular sovereignty became more meaningfully present in Leveller thought than in the thought of parliamentarians such as Henry Parker partly because the Levellers read the story of an original state of nature and contract of government differently. Parker too had used the device of consent to argue that power was limited by what rational people with an eye to their own self-preservation would have instituted. But that choice was long in the past, and they had chosen parliament as the safeguard to protect themselves against the excesses of kings – although even Parker suggested that "'some things they have reserved to themselves out of Parliament, and some thing in Parliament"' (Parker 1642), suggesting that even outside parliament, the people retained some rights that they could not or did not give away. But Lilburne's state of nature was not just in the past – he said that "'every particular and individuall man and woman, that ever breathed in the world since [Adam and Eve]... are, and were by nature all equall and alike in power, dignity, authority, and majesty"' (Lilburne 1646). If people still have their original equality, and cannot sacrifice it except through "'mutuall agreement or consent,"', the exercise of individual consent comes into the present day of routine politics, rather than being confined to the distant past when the constitution was established, or fused into the collective, representative, but unaccountable acts of parliament. That picture is reinforced by Overton's account of the flowing of power between the sovereign people and their betrusted MPs – and, as he pointedly says, "'no further"' (Overton 1646a). Given the Leveller insistence on annual parliaments (a step further than the army radicals' demand for biennial parliaments, as seen in the first Agreement of the People), this exercise of people's original freedom was to happen often.

The rights of individuals play a large part in Leveller thought, and both Lilburne and Overton present very positive pictures of the "'power, dignity, authority, and majesty"' which these individuals enjoy in an original state of freedom – as Davies says, a kind of original individual "'sovereignty"' is suggested by Overton's famous notion of "'self-propriety"' (Overton 1646b). But we should not leap to conclusions about the implications of this kind of individualism, which, while undoubtedly a part of the ancestry of liberalism, did not necessarily lead to individualistic conclusions in political terms, but existed within the broader web of a national community bounded by law. The Levellers wrote often about the individual rights that needed to be defended, but when they described what these rights were they either called them "'national"' and "'legal"' rights, or "'natural"' rights – indeed they combined the two descriptions as if they unproblematically aligned, as they interpreted national law in the light of an "'equity"' which almost equated to simple reason (Overton 1647). Depicting rights as national or even natural was a polemical move which was designed to show that these were not particular privileges or grants available only to a few. Every individual enjoyed them – but this emphasis on individual rights was intended to universalizse, as much as to individualizse, the enjoyment of these rights, as telling comments about "'common rights"' or "'common right and freedom"' demonstrate. Leveller language created a vivid sense of a community where people were to defend not merely their own but each other's rights, and where the struggle of an individual (most often John Lilburne) against his own oppression was mobilizsed to bring into being a national community of "'free-born Englishmen"' who knew their own rights, not least through reading Lilburne's pamphlets, and were prepared to defend them by supporting him in collective action. In religion the autonomy of the seeking conscience would lead to diverse insights in different people (The Compassionate Samaritane declared that no "'agreement of judgement"' was to be expected "'as longe as this World lasts"'), and they were indeed obliged to rely on themselves in this individual search for truth. However, in politics the Levellers were considerably more willing to teach their followers how to understand the law and their own rights, so that the exercise of honest political conscience could be expected to reach rather more uniform conclusions.

One of these conclusions was that there were spheres of life protected from the exercise of political power. Unexpectedly, however, this not because these were spheres where the individual exercised an inviolable self-control, but, as Overton put it very clearly, because these were spheres where even the individual had no right to govern him or herself – and hence no power to give away to a magistrate. Individuals had the duty to search their own consciences, but they did not have the right to bind them; and, as Overton made clear, "'as no man by nature may abuse, beat, torment or afflict himself, so by nature no man may give that power to another, seeing he may not doe it himselfe"' (Overton, 1647). Government was limited because individuals were limited too – by God and nature. The Levellers feared the corruption of representatives and governors – fears born partly out of bitter experiences of imprisonment by the very parliament they had supported in the civil war. But their positive picture of the "'majesty"' of equal individuals before they had consented to government translated into a positive picture of the natural and benign phenomenon of government by mutual consent and agreement, a phenomenon which they hoped to recreate through an Agreement of the People.

References :

Como, David. 2018. Radical Parliamentarians and the English Civil War.

De Krey, Gary. 2018. Following the Levellers: Political and Religious Radicals in the English Civil War and Revolution, 1645-1649.

Dzelzainis, Martin. 2005, "History and ideology: Milton, the Levellers, and the Council of State in 1649," Huntington Library Quarterly 68: 1/2

Foxley, Rachel. 2013. The Levellers: Radical Political Thought in the English Revolution.

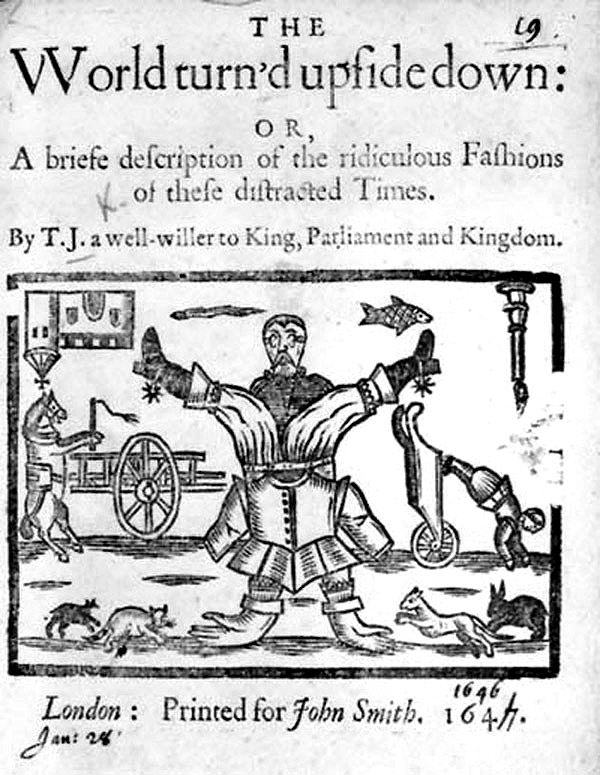

Hill, Christopher. 1972. The World Turned Upside Down.

Lilburne, John. 1646. The Free-mans Freedom Vindicated.

Overton, Richard, 1645, The Araignement of Mr Persecution.

Overton, Richard. 1646a. A Defiance against all Arbitrary Usurpations.

Overton, Richard. 1646b. An Arrow against all Tyrants and Tyranny.

Overton, Richard. 1647. An Appeale from the Degenerate Representative Body... To the Body Represented.

Parker, Henry. 1642. Observations upon some of his Majesties late Answers and Expresses.

Raymond, Joad. 1996. The Invention of the Newspaper.

Rees, John. 2016. The Leveller Revolution.

Zaret, David. 2000. Origins of Democratic Culture: Printing, Petitions, and the Public Sphere in Early Modern England.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.