Liberty Matters

Imperfect Labels

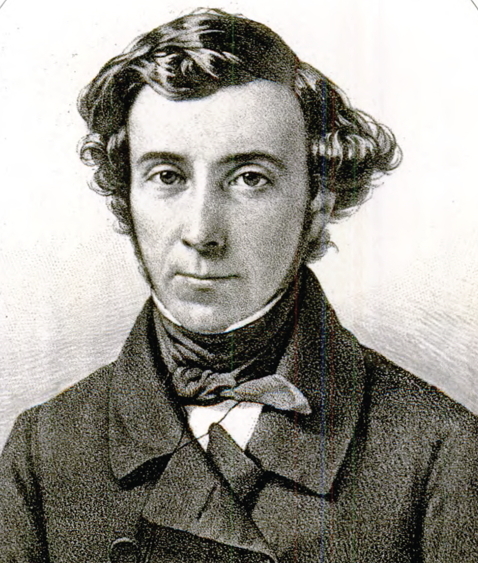

Filippo Sabetti is certainly right to remind us that Tocqueville was an advocate of civilizing empire and that his support for French colonialism in Algeria is at some tension with his liberalism. On the other hand, there is a growing academic industry that aims to summarily indict Tocqueville for his views on empire rather than making an elementary effort to understand them. As Raymond Aron once put it, “[T]his prince of the mind did not turn his back on either the greatness of the country or the liberty of its citizens.” A careful reading of Tocqueville’s writings on empire shows that he thought it a worthy pursuit of a free and great people, but that he never justified cruelty or the injustice that was slavery. His beautiful testimony against slavery that appeared in The Liberty Bell in 1856 made clear his absolute opposition to “personal servitude” and “man’s degradation by man.” “An old and sincere friend of America,” he lamented that slavery tarnished her glory and gave support to her detractors. He hoped “to see the day when the law will grant equal civil liberty to all the inhabitants of the same empire, as God accords the freedom of the will, without distinction, to the dwellers upon earth.” And he had nothing but contempt for his friend Arthur de Gobineau’s emphasis on the allegedly scientifically founded “inequality of the races.” As he wrote to Gobineau on January 24, 1857, “Christianity manifestly has tended to make all men brothers and sisters.” Tocqueville remained faithful to that Christian insight even as he supported France’s right to exercise what I have called civilizing empire. These tensions deserve reflection rather than moralistic disdain of the type put forward by contemporary academics.

On another front, Aurelian Craiutu helpfully reminds us of the myriad ambiguities that make it difficult to label once and for all Tocqueville’s “strange kind” of liberalism. Perhaps Pierre Manent provides a helpful clue when he suggests that there was also a tension in Tocqueville’s mind between justice and grandeur. We underestimate Tocqueville as a thinker when we fail to see that his judgments of the “head” also had a place for magnanimity or greatness of soul. To be true to democratic justice while still honoring man’s capacity for greatness might even be said to be a serviceable definition of the Tocquevillean enterprise. Labels such as “conservative liberal” and “aristocratic liberal” are necessarily imperfect efforts to do justice to that insight.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.