Liberty Matters

The Relevance of the Ancients

People who think it’s a good idea to read classical texts are sometimes challenged with “Why should I read something like that? It isn’t relevant to my life.” There are a couple of wrong-headed ideas baked into such a challenge. One is the presupposition that a work from another culture 2000 years ago cannot be relevant. Another is the idea that only one sort of relevance would count as a justification for reading something that old. Both of these are false: classical texts can be worthwhile even if they lack topical relevance, but also, they tend to contain more relevance than people realize.

People who think it’s a good idea to read classical texts are sometimes challenged with “Why should I read something like that? It isn’t relevant to my life.” There are a couple of wrong-headed ideas baked into such a challenge. One is the presupposition that a work from another culture 2000 years ago cannot be relevant. Another is the idea that only one sort of relevance would count as a justification for reading something that old. Both of these are false: classical texts can be worthwhile even if they lack topical relevance, but also, they tend to contain more relevance than people realize.Roosevelt Montas’ lead essay does a great job articulating the ways in which many classical texts transcend time and place, and speak to the human condition in a broad way, and I couldn’t agree more that “communion with the ancients both enlarges our human experience and cuts it down to size….We neglect a precious aspect of our humanity when we abandon the form of wealth that ancient texts offer us for free.” Sadly, I fear that few people will listen to him, for reasons his essay explains: the increase in both disciplinary specialization and the pre-professional ethos of higher education today. If the “point” of higher education is preparation for the high-tech job market, why should anyone bother with Aristotle?

It's actually even worse than Montas thinks. Even within the discipline of philosophy, many contemporary philosophers have advanced the argument that we shouldn’t teach, or even care about, ancient philosophers. For some of them, the reasons are the ones Montas notes, that they’re misogynistic or racist and so on (e.g., don’t bother with Aristotle because he thinks women are mentally inferior to men). For others, the objection is that the ancients lacked the scientific advances that have led to today (e.g., don’t bother with Aristotle because he didn’t know about Arrow’s theorem). But while it’s certainly true that ancient philosophers may be wrong about this or that empirical matter, it’s fallacious to infer that we therefore have nothing to learn from them.

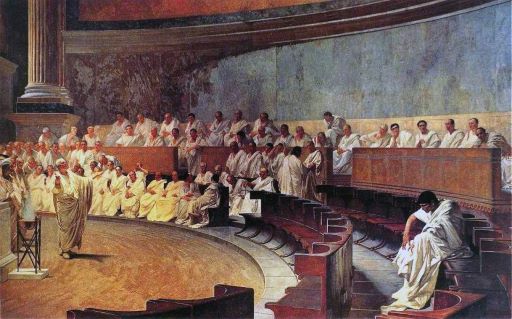

In one sense, this is the answer to the “relevance” question: if there’s anything at all to be learned from something, that makes it relevant. Do we have anything to learn from the ancients? Of course we do. Outside of the natural sciences, it simply isn’t the case that “newer” implies “truer.” Sometimes older wisdom is shown to be flawed, other times it proves itself to be enduring. Imagine a great and powerful nation that fancied itself to be committed to freedom and democracy, but because it was at odds with other quasi-imperial powers, found itself obliged to disregard human rights and curtail some freedoms, focusing perhaps too many of its resources on combat action despite the dubious rationale for the long war it was in. The classically-minded reader will have perceived that I am referring not to the United States, but to classical Athens, as documented in Thucydides’ account of the Peloponnesian War. It’s impossible to think Thucydides has no relevance for the modern world unless one has never read Thucydides. His insights into power, justice, and freedom are not locked into his time, but are timeless. That’s not to say that he, or any other ancient thinker, should be presumed wise because he is from ancient times. But it’s also false that he should be presumed foolish or useless because he is from ancient times. As long as there is political power, it will always be relevant to think about its justification and proper scope. As long as there are people, it will always be relevant to think about how we should live and interact with each other.

The counter-argument is, yes of course we need to keep asking those questions – that’s why reading the classics is useless; we have new, better sources. But that begs the question. Some people justify the history of philosophy on the grounds that it’s helpful to contextualize contemporary inquiry by reference to where those inquiries originate. And that’s true, but it is not the sole, or most important reason. The more important reason, I would argue, is the sort of reason I suspect Montas would agree with – that there is in fact enduring wisdom in so much of the classics. Plato’s grand analogy of the soul-as-city, Aristotle’s account of practical reason and its role in human virtue, Thucydides’ reflections on power – these are worth reading for their insight, not as mere historical curiosities.

And of course, Montas’ argument isn’t limited to philosophical works. Literature too can be appreciated across time and place. A beautiful poem or a moving drama is something that speaks to the human condition in some way, or excites the imagination, or hits an emotional chord. The idea that there is an expiration date on a work’s ability to do this is ridiculous, so in one sense, it’s sad that Montas even felt obliged to refute it. But on the other hand, since people do make this ridiculous argument, I am glad he did, and he does an eloquent job doing so.

There is the question, which Montas speaks to, of which books in particular should count as “the canon.” I wonder if that’s a question we need to answer. If I claim that there’s some great value in reading Aristotle, that’s either true or false on its own merits, and isn’t a function of whether something else another person might name is also of great value. If we took the idea of “liberal education” seriously, as Montas recommends, we would be glad to have an ever-expanding canon, and it wouldn’t be zero-sum. But – and this is one of his points – there are countervailing pressures in the academy that make it become zero-sum. Many majors are facing pressure from accreditation boards to increase the total credits required for the major, leaving fewer opportunities for study of anything not within that major. And “general ed” requirements, which one might think would be a safe haven for “great books,” have often been distorted by turf wars which elevate departmental advantage over student benefit.

Sadly, there are no obvious and simple solutions to this problem. Until some of those start to appear, the best we can hope for is that those who appreciate the insights of the ancients continue to defend the value in reading them.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.