Liberty Matters

The Mayflower Compact Landed on Us?

Sarah Morgan Smith's fine essay is a great way to begin celebrating the 400th anniversary of the Mayflower Compact. Coming as it did a year after the first meeting of what, in time, would become Virginia's "House of Burgesses" it reminds us of the colonial roots of American republicanism. It is neither slavery nor aristocracy that set colonial English America apart. The prevalence of republican practices and politics made the colonies, particularly those in the North, different from England and the other nations of Europe, and probably different from most nations on earth at the time.

Sarah Morgan Smith's fine essay is a great way to begin celebrating the 400th anniversary of the Mayflower Compact. Coming as it did a year after the first meeting of what, in time, would become Virginia's "House of Burgesses" it reminds us of the colonial roots of American republicanism. It is neither slavery nor aristocracy that set colonial English America apart. The prevalence of republican practices and politics made the colonies, particularly those in the North, different from England and the other nations of Europe, and probably different from most nations on earth at the time.What set the colonial North apart from the colonial South was the importance of dissenting Protestantism. As Edmund Burke put it in his Speech on Conciliation:

All protestantism, even the most cold and passive, is a sort of dissent. But the religion most prevalent in our Northern Colonies is a refinement on the principle of resistance; it is the dissidence of dissent, and the protestantism of the protestant religion. This religion, under a variety of denominations agreeing in nothing but in the communion of the spirit of liberty, is predominant in most of the Northern provinces; where the Church of England, notwithstanding its legal rights, is in reality no more than a sort of private sect, not composing most probably the tenth of the people.

Burke probably recognized what Smith calls "a logical consequence of the religious convictions of the majority of the Plymouth colonists." The doctrines of sola scriptura, with the attendant focus on the responsibility of each individual to read and seek to understand the Bible for himself, especially in the Calvinist version set men and women on a republican path. It is probably no coincidence that the Oxford English Dictionary lists a 1640 reference to "some . . . can be content to admit of an orderly subordination of several parishes to presbyteries, and those again to synods; others are all parochial absoluteness and independence" as its first entry for "independence," and "[each congregation is] an entire and independent body-politic, endued with power immediately under and from Christ" as its first entry for "independent."

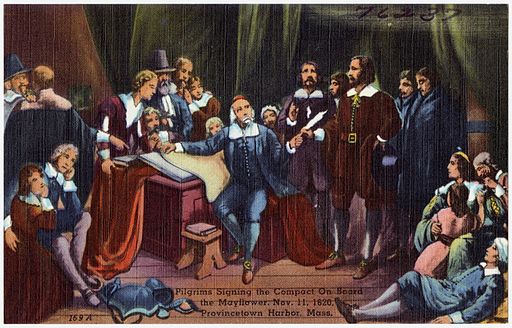

Historically speaking, or perhaps sociologically speaking, the political and religious doctrines one finds in any given community tend to be congruent with each other, else the society will be fraught with tension. Hence it should not surprise us that when the Mayflower found itself so far North that its passengers were outside the Virginia Company's reach, they turned to compact to form themselves into a political community, a reflection of how a separatist congregation forms itself. The journey from 1620 to 1776, and thence to 1865 is not all that long. And that congregational independence was the germ, perhaps one should say a germ, of the independence of the colonies from Britain.

But dissenting Protestantism is not all the same, and it's worth noting some of its variations and some of the nuances. Roger Williams, after all, tried living in both Massachusetts and Plymouth before he (after being exiled) founded Rhode Island and embraced religious liberty. I'm not sure it's quite correct to say that "membership depended upon an individual's ability to offer credible profession of faith." It would be better to say that it was dependent upon what was taken as credible testimony that one was of the elect. From a certain perspective, I suppose, that's the same thing—only the elect have true faith, but in modern ears we don't hear the difference. Similarly, the epistemic humility that Smith notes was probably narrower in practice than her essay suggests, as the case of William reminds us. If one is stuck in a world of sinners, and if one is oneself a sinner, the result is a certain humility. But that humility itself is born of a doctrine that is not to be questioned in public.

Of more importance for the questions of toleration and liberty is the question of who was part of the Plymouth political community. The William and Mary Quarterly article Smith cites notes that "some free adult males were by then being denied the opportunity to participate in the political life of the plantation." William Bradford was elected governor in 1621 by "the free adult males who were stockholders in the company." When free men who did not own stock in the company arrived, they had to consent to obey the laws of the colony, including paying taxes, but "they were apparently not, however, admitted to political citizenship." In time Plymouth would allow others to vote, but not everyone: "Plymouth had never admitted to citizenship Quakers or others who rejected the need for a trained ministry, and in fact the colony promptly disfranchised any persons who showed sympathy for the Quaker religion." It might very well be, and probably is true that the tendency in dissenting Calvinism is toward religious liberty and citizenship for adults, but Plymouth, however far it went, did limit the doctrines.

And that point reminds us that "Liberty" can apply to two things. It can belong to individuals and/ or peoples or communities. Some of the tensions in the ideas of the New England Puritans are in the tension between those two ideas of liberty. The principle the Plymouth Separatists embraced, that each Congregation was independent, a spiritual island to itself as it were (in contrast to the ecclesiology that dominated in Massachusetts, usually called "Congregationalist," as opposed to "Separatist," which held that each Congregation had the right to gather itself and appoint its minister, but which was, nonetheless, part of a larger English communion), was, in the first instance, about the liberty of the Congregation. In Plymouth, unlike in England, they were free legally to form church communities that way. But that doctrine itself was, as Smith suggests, an outgrowth of the spiritual individualism of dissenting Protestantism. Hence the Plymouth settlers, unlike so many other colonizers, turned to Compact to create political society, and, hence what they took to be religious liberty would, in time, help to produce a land which respected a larger liberty of conscience.

All that, finally, raises a perhaps disturbing question, if American Protestantism is fading, must our liberalism go with it?

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.