Liberty Matters

Can Liberal Constitutionalism Instruct?

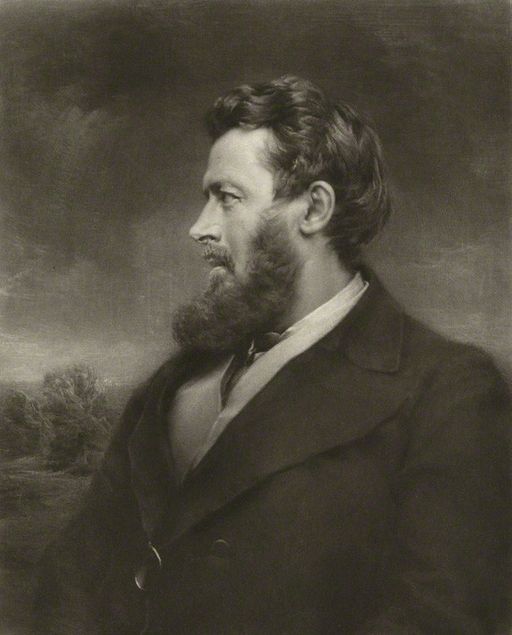

Suppose one reads Walter Bagehot's English Constitution naively, at least the first time through, not from the perspective of our contemporary constitutional troubles nor by placing him in some historical school—"the nineteenth-century jurisprudence of positivists and pragmatists,"" suggests Adam MacLeod—but beginning with how he describes himself and the task he undertakes. Bagehot identifies himself as a Liberal, a member of a then-new, later dominant, now-defunct political party, but he is not writing a partisan tract.[1] At least twice he refers to "political philosophy" as the perspective he takes, at least for a moment of analysis, detached from adherence not only to a political party but to a particular country, even though he identifies himself as an Englishman and is principally, though not exclusively, concerned with the English constitution.

I think he means, at least at the outset, to analyze the English constitution as Aristotle analyzed the constitutions of the Greek cities of his own era, treating the term "constitution" as Aristotle did his analogous term, "politeia," to describe who rules in the city, or rather, to identify what kind of people rule and the forms by which their rule is exercised.[2] Bagehot mentions the Greek city and finds an interesting analogy between its development and the rise of modern politics,[3] but he is also aware that a modern nation-state is not the same as an ancient polis, so his analysis of its form is not bound by Aristotle's terminology. Still, like Aristotle he treats the constitution as a political form, not a higher law; he is more concerned with who actually rules than with traditional practices; and he is particularly intent on praising the rule of wisdom, which, by its anchor in experience, its mastery of particulars, and its insusceptibility to being nailed down to rules, seems consonant with, if not the same as, classical phronesis.

At the outset, Bagehot contrasts his analysis with what he calls the literary theory of the English constitution—he doesn't name its source, but he seems to have in mind Montesquieu and Blackstone—which describes English government as based on two principles, the separation of powers and balanced government.[4] However accurately this account may have explained British politics in the eighteenth century, it misunderstands the actual functioning of that politics in the nineteenth, particularly after the Reform Bill of 1832, which established the sovereignty of the nation, with the House of Commons as its instrument. More precisely, it established cabinet government, with Commons now to be understood as the elected body that elects and holds accountable the government, where the real power lies—so long, that is, as it retains the confidence of the nation.[5] The old theory, or at least its principle of separation of powers, was adopted by the Americans and used to construct our presidential system, which serves throughout the book as a foil to Bagehot's cabinet government. The latter in almost every respect proves superior in his eyes, not only in bringing wiser men to power, but in encouraging them publicly to debate what policy would be best and thereby to form as well as reflect the public opinion of the nation. He is well-aware that the parliamentary and the presidential systems offer the world the great alternative models of self-government, and that the world is interested in knowing which would be more advantageous to adopt.[6]

The brilliance of Bagehot's account is in his explanation of how the complex manners of parliamentary conduct serve at once to ensure the rule of the wise and the consent of the governed. Although in the literary theory a legislative body, Parliament in practice functions as an electoral college and an ongoing inquest, ensuring that able ministers are selected and then held accountable for their actions. It might seem irrational to shuffle portfolios among them, allowing them no time to develop expertise in the units they purportedly head, but in fact it ensures both that each administrative department has an able advocate in Parliament and reciprocally that it receives constructive criticism from the government.[7] While election by the assembly might seem to make the executive too dependent—this was the Americans' reason for establishing a separate process[8]—the ability of the prime minister to dissolve the house and appeal to the people in a new election reverses the direction of dependency, at least so long as the government is confident of popular support. (Bagehot would easily have predicted the 2011 Fixed Term Parliaments Act would wreak havoc in this finely balanced system.[9]) As for the monarchy and the House of Lords, Bagehot calls them ceremonial rather than efficient, critical to the smooth functioning of the English system at the time, though he speculates as to whether analogous institutions could be created anew in countries without a feudal heritage. He lays out the advantages and disadvantages of having a constitutional monarch, weighing the charm of ancient tradition and its easy legitimacy against the danger, exemplified by George III, of a mad king; he endorses the creation of life peers to keep the second house active, useful, and accepted in a democratic age, but not to be imitated in the colonies, where an upper house draws political talent away from the representative body where it is most needed to ensure compromise and civil peace.

MacLeod quotes Bagehot's distrust of, not to say contempt for, the "poorer and more ignorant classes" whose attachment to the constitution comes not from their understanding of its rationality and balance but from the illusion of royal authority to which they cling. While this part of his theory indeed seems a bit precious, not to say precarious, dependent on the habits of deference in the people, I don't read Bagehot here as proto-progressive paternalist, for several reasons. First, he makes clear that Parliament represents the middle classes, adept at business and fully capable both of discerning their own interests and of choosing someone to express them. In America and in the antipodal colonies, where the task of building settlements in the wilderness imposed equality at the outset and thus implanted it in the culture, the middle class dominates society and politics unproblematically; the problem is the legacy of feudalism in Europe, though it has the advantage, at least for the time being, of making available for political service a highly educated aristocracy naturally adept at rule.[10] Second, especially in the preface to the second edition, written after the further expansion of the franchise in the 1867 to include the working classes—and, he notes, the simultaneous disappearance of Lord Palmerston's generation of pre-1832 statesmen from the scene—Bagehot expresses his doubts about incorporating the working class voter without preparing him for the responsibilities of active citizenship. Here the parties earn his blame in the short-term, and his fear of subjecting the government of England to the prejudices of the working class is palpable, though not, I think, un-Aristotelian.[11] For third, while Bagehot is clearly a man of the Enlightenment and is confident of the advances of a dynamic, modern society, he is not above expressing a healthy skepticism of the capacity of modern science to replace prudence in the governance of human affairs, or at least to suggest something is lost in modern discourse. After quoting Darwin at length, he writes: "I am not saying that the new thought is better than the old; it is no business of mine to say anything about that; I only wish to bring home to the mind, as nothing but instances can bring it home, how matter-of-fact, how petty, as it would at first sight look, even our most ambitious science has become."[12] Whether his own political science confirms or by self-consciousness escapes this indictment is the question.

If pettiness is unworthy of a great mind or a great people, what elevates? MacLeod's attention to what Bagehot doesn't say—how in contrast to the English tradition before him, he says almost nothing of religion, or of natural law; how he treats American government as different only in its machinery, not in its understanding of natural rights—is suggestive, and less for the correction of Bagehot's attitude toward the poor, whom I think he believes will eventually be incorporated into modern society even in England, than for the discernment of what an adequate education in prudence entails. I admit I am skeptical when I read "Our institutions have failed." That's what leading political scientists were writing about the American presidency—and the British were writing of their own system—in the 1970s, and then along came Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, who showed that the institutions can indeed be made to work when aiming to achieve what they were designed for, not the solution of every human problem, but the support and defense of a free society. Liberals like Bagehot—or for that matter, James Madison or Alexis de Tocqueville—still have much to teach us about how our political institutions can work soundly to effect the adjustment of clashing interests in the name of justice and the general good, even when they have little to say about how freedom is grounded in the human good or risk descending into hubristic progressivism should they try. Or perhaps it is institutions such as churches and universities that have really failed—the ones responsible for guiding lives and elevating minds—and our political crisis is the consequence, not the cause. If that is Adam MacLeod's point, I agree.

Endnotes

[1.] Walter Bagehot, The English Constitution, 2d ed. (London: Oxford University Press, 1928 [1872]), no. 5, p. 134.

[2.] Aristotle, Politics, book III, ch. 4 ff.

[3.] English Constitution, no. 9, p. 242 ff.

[4.] Ibid., no. 1, p. 2.

[5.] Ibid., no. 1, p. 11; no. 5, p. 115; no. 8, p. 225 ff.

[6.] Ibid., no. 1, p. 14 ff; no. 7, p. 224.

[7.] Ibid., no. 6, p. 156 ff.

[8.] See Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, James Madison, The Federalist, no. 68.

[9.] See Abram N. Shulsky, "Constitutional Change Made Easy, UK Edition," Law & Liberty, December 19, 2019.

[10.] English Constitution, no. 8, p. 232 ff.

[11.] Ibid., no. 5, p. 147; no. 8, pp. 234-240; Introduction to the second edition, p. 265 ff. Cf. M.J.C. Vile, Constitutionalism and the Separation of Powers (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1967), p. 224.

[12.] English Constitution, no. 7, p. 223.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.