Liberty Matters

A Burning Romance with Ideas, a Legacy More Tragic than Triumphant

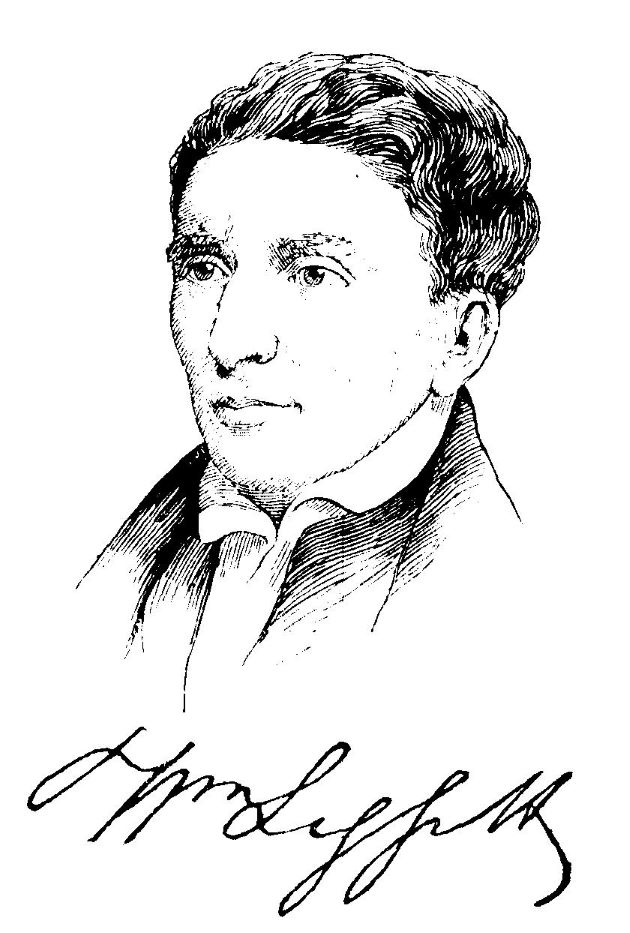

I will begin by noting that in his lead essay, Phil Magness has given us a perfectly accurate and succinct rendition of William Leggett's guiding philosophy of equal rights, especially in noting the "timeless character" which marked virtually everything he wrote. Yet I have one perhaps crucial quibble: "Locofoco" was not a brand of matches; it was an American bastardization and portmanteau of the Italian words for "fire in motion." Locofoco referred to the newly invented friction-lighted tips with which we are all now so familiar. Put the match into motion, strike the tip, and the fire burns hot. Friends, enemies, observers of all kinds agreed: William Leggett was among the fieriest of individuals in a generational conflagration. The heat from his pen—perpetually in motion—lit a republican, egalitarian bonfire.[27]

I will take up Phil's charge to track down Leggett's "political legacy," the marks he left on two generations of radicals. Leggett was without qualification a libertarian hero whose life was bright but short; his story was a burning romance with ideas, but I'm afraid the longer tale of his legacy was more tragic than triumphant.

As a young, restless poet (suicidal from navy life) Leggett presaged the course of his future movement:

HOPE When youthful hearts are light and true, And all is fair around us, The future breaks upon our view In every bright and pleasing hue— For Hope's sweet spell hath bound us, And all seems fair around us. But ah! too soon we're doom'd to find The scenes that look'd so charming, Beset with thorns, with snares intwined, That Hope is false, and Fortune blind, And dangers most alarming, Where all had seem'd so charming. Yet Hope hath still her pleasing power, Although she's a deceiver! And e'en while storms above us lower, She paints so bright the future hour, We cannot but believe her— Although she's a deceiver! Thus we stray on in quest of joy, The dupes of Hope forever! Earth hath no good without alloy, And sweetest pleasures soonest cloy, We soonest from them sever— The dupes of Hope forever!--Leisure Hours at Sea, 1825

The 1835 mails controversy earned him an "excommunication" from the Democratic Party and began the Locofoco movement. The Locos' most bitter enemies were not Clay Whigs—the worst of all were the "Bank," or "Monopoly," Democrats who ran Tammany Hall. The conservatives hated Leggett for all of his radicalism, free banking, and abolition alike. The Washington Globe assailed him for a "spirit of Agrarianism" and "Utopian temper," which had him forever "running into extremes." Leggett "knew no medium" on the tariff and banks, but there was one thing that could not stand: "He has at last, and we are glad of it, taken a stand which must forever separate him from the Democratic Party. His journal now openly and systematically encourages the Abolitionists."[28]

Leggett's ideas caught fire and spread nationwide to varying degrees, inspiring frenzied activity. In Abram D. Smith, Leggett provoked the restless spirit of revolution. Smith and like-minded "Patriots" met across the northern borderlands in secret, communicated by cypher, drilled for rebellion against the British Empire, and planned for the future of a free Canadian republic. Smith was even elected "President of the Republic of Canada," though the rebellions were dismal failures. In Thomas W. Dorr, Leggett's writing invoked the dormant beast of domestic insurrection. Dorr and his followers attempted to reinvigorate the grand American tradition of spontaneous, popular constitutional conventions to give the state of Rhode Island a new government. Dorr and his "People's Charter" received support from the majority of the state's male population, but the so-called "Landholder's regime" refused to give way. In the end, though the Dorr War was a powerful moment when locofocoism threatened revolution, the old order resoundingly won out. In part the Dorrites defeated themselves with internal strife over race and slavery. Dorr was an abolitionist and public about that, but many Dorrites believed their success hinged on a national political coalition including slaveholders. Convinced that Dorrism required racism, a large majority of the People's Convention restricted voting to white men; convinced that Dorrism was "a tremendous abolition plot," the Tyler administration and southern politicians refused their support. The revolution died choking on politics.[29]

With each major event-in-radicalism throughout the 1840s and '50s, the old Locofoco coalition splintered and factionalized in the same manner, whittling the movement away to nothingness. Locofocos peeled off into camps of ideological purists and pragmatic realists. The ideologues venerated the spirit and memory of William Leggett and applied their ideas thickly across the intellectual landscape—they were the young and rowdy revolutionaries invading Canada; they were the antislavery Dorrites and clam-baking separatists who refused to cooperate with the victorious Charter government; they saw President James K. Polk for the slaveholding, plutocratic imperialist that he truly was and bitterly refused to support his war on Mexico; they deftly balanced support for the 'lawless' New York Anti-Rent War and the New York Constitution of 1846, which abolished the vestiges of landholder feudalism in that state and democratized the process of incorporation; they pioneered the coalition of Democrats and more whiggish Liberty Party supporters that solidified into the Free Soil Party in 1848; Leggettian purists like Canada's former President Abram D. Smith found their way into every corner of politics, including Smith's own seat on the Wisconsin Supreme Court (where he nullified the Fugitive Slave Act); they helped found the Republican Party and finally implemented the greatest of Leggett's reforms—the abolition of property rights in human beings.

Pragmatist Locofocos sought more "thin," quantifiable policy gains or to enrich themselves with election or patronage appointments. Office-climbers like Polk or James Buchanan paid lip service to locofocoism when politically expedient and made the right overtures to the right public leaders without being obliged to follow through on the whole philosophy. There were figures like the early Locofocos Fitzwilliam Byrdsall and Levi Slamm, both of whom allied with John C. Calhoun to achieve free trade at the expense of Leggett's antislavery; there were the Fernando Woods of the world, who secretly worked for Martin Van Buren by infiltrating a New York Calhoun committee (earning Wood nothing really but Van Buren's contempt); there were the "Manifest Destinarians" who flooded pop culture with their ideas (including Dorrite clam-bake speeches) and whose votes helped place Polk in the White House; there were "dough-faces" like Franklin Pierce, who supported Dorrism and economic locofocoism but did all he could to court southern votes; and there were life-long Leggettians like Samuel Tilden, who opposed the Civil War, fought his own twin war for reform and against corruption, and almost won the presidency on a platform of conciliation to the defeated South at the expense of African Americans' universal, equal rights.

Leggett's own supposed adherents consistently betrayed his broad antimonopoly political ethic. In this way, Leggett posthumously lost the "triangular contest" of American politics, which he recognized so clearly in his own lifetime—there were the broadly interventionist Whigs, the "Monopoly Democrats," and the Locofoco radicals. Yes, his philosophical and political children could claim significant victories, but each of them came at inestimable costs to the overall intellectual framework. Abolition, corporate reform, banking reform—all were important to those whose lives they touched, but the methods of democratic politicking chosen to achieve them buried the Locofoco movement and killed their system as such.

As their flame sputtered out and the smoke cleared, though, the package of ideas did remain behind, powerful as ever, just awaiting a new generation of activists to relight the match. Benjamin Tucker took up the torch. He no longer had locofoco to use in his own "war on monopoly," so Tucker imported a new word from Europe: libertarian. [30]

Endnotes

[27.] All of the general information I will cite about Leggett and the Locofoco movement can be found more fully documented in my dissertation: Anthony Comegna, "'The Dupes of Hope Forever': The Loco-Foco or Equal Rights Movement, 1820s-1870s" (The University of Pittsburgh, Ph.D. dissertation), 2016, and Fitzwilliam Byrdsall, The History of the Loco-Foco or Equal Rights Party: Its Movements, Conventions, and Proceedings with Short Characteristic Sketches of Its Prominent Men (New York: Burt Franklin, 1967, originally published in 1842). For more information about the origins of the term locofoco as related to matches, see James Rees, "Locofoco" in Book of Origins, Saturday Evening Post, November 10, 1877, and "Locofocoism," The Locofoco, Pittsburgh, August 22, 1844.

[28.] Walter Hugins, Jacksonian Democracy and the Working Class: A Study of the New York Workingmen's Movement, 1829-1837 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1960), pp. 28-33; Byrdsall, History of the Loco-Foco Party, pp. 18-19.

[29.] On Abram D. Smith in the Canadian rebellions and as the Wisconsin state Supreme Court judge who nullified the Fugitive Slave Act (more below), see Ruth Dunley, The Lost President: A. D. Smith and the Hidden History of Radical Democracy in Civil War America, Atlanta (Athens, GA: The University of Georgia Press, 2019). For the Dorr War, its Locofoco origins and its mixed consequences, see Erik Chaput, The People's Martyr: Thomas Wilson Dorr and His 1842 Rhode Island Rebellion (Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press, 2013) and Comegna, "'The Dupes of Hope Forever.'"

[30.] For example, see Benjamin R. Tucker, "Land and Rent" in Instead of a Book, by a Man Too Busy to Write One (New York: B.R. Tucker,1897), p. 320. <https://archive.org/details/cu31924030333052/page/n339>.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.