Liberty Matters

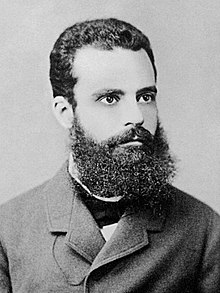

Pareto and the Death of Liberal Europe

I've learnt a lot from the wonderful contributions of Giandomenica Becchio, Rosolino Candela, and Richard E. Wagner. One thing they all convey to the reader is that Pareto's work is a tremendously rich mine and that it can provide us with many takeaways, even when limiting the exploration to the seemingly narrow subject of Pareto and political realism.

I've learnt a lot from the wonderful contributions of Giandomenica Becchio, Rosolino Candela, and Richard E. Wagner. One thing they all convey to the reader is that Pareto's work is a tremendously rich mine and that it can provide us with many takeaways, even when limiting the exploration to the seemingly narrow subject of Pareto and political realism.In his beautiful essay, Professor Wagner argues that "Pareto was a liberal for sure, but it was his interest in scientific explanation that animated his efforts." In a sense, such a remark in part completes and in part defies my own portrait of Pareto's journey between classical liberalism and political realism.

Wagner points out that, ever since his youth, Pareto always strove to achieve the greatest scientific accuracy:

"Pareto's interest in economics stemmed more from his scientific interests than from a desire to advocate for liberal values and practices. Sure, Pareto engaged in plenty of advocacy on behalf of liberalism. Still, Pareto was more a theorist than an advocate."

In a 1913 letter, Pareto himself says that "I set out with accepting the theories of the so-called classical economics, as they seemed—and still seem—to me more scientific than those of their rival schools." (Pareto 1913, 801) Recalling his youthful efforts "in defence of economic freedom," which he dismisses as "all wasted time," Pareto remarks that they were written when he still "did not understand the profound difference that exists between the operating [operare] and the knowing; a difference so profound in social sciences, that one thing is the often the opposite of the other." The ambition for scientific veracity produced very different approaches in Pareto as an economist (with his commitment to the idea of equilibrium)[6] and as a social scientist at large (with his emphasis on the role of irrationality).

Giandomenica Becchio notes:

"Pareto belonged not only to the two traditions mentioned by Alberto (classical liberalism and political realism) but also to the tradition of modern moralists (Montaigne, Bayle, Mandeville, Bentham) who focused on the analysis of human passions and irrational motivations of human behavior."

Wagner and Becchio thus seem to call for very different readings of Pareto. Was he a scientist or a moralist? I think Wagner and Becchio are both right: he was both. Becchio reminds us of the role of irrationality in Pareto's sociological thinking; Wagner underlines how this happened at the times of his classical-liberal militancy: "Pareto was convinced that a social system based on free and open competition was superior to any of the options where the few dominated the many. Yet free and open competition showed no signs of winning any kind of popularity contest."

Could it anyway?

As we agree that there is—broadly speaking—no contradiction between Pareto's younger, committed liberalism and his later, more dispassionate look at political facts, I'd like to spend a few words on his relationship with, so to say, "official liberalism." This may also help in clarifying, as Rosolino Candela asked me to do in his generous and profound piece, what I meant by saying that Pareto's political realism is not incompatible with a classical-liberal worldview, but is so with a classical-liberal program.

Pareto's direct contacts with politics, and his following it closely in the context of his free-trade advocacy, clearly played a role in shaping his political realism. But in understanding how "free and open competition didn't win any popularity contest," the performance of self-described liberal parties may have played a crucial role.

I've already mentioned Pareto's stance on anti-clericalism. Fiorenzo Mornati speaks of Pareto's "religious liberalism." Pareto thought the separation of church and state meant that the state should ignore the church, leaving it alone, rather than actively meddling in religious matters. On the contrary, he saw freedom of religion being "under attack by 'materialists and idealists' in the name of the age-old doctrine of the all-powerful state." (Mornati 2018, 134) Hence Pareto, right from the beginning, was alert to the possible shortcomings of his fellow travellers.

Yet the situation got much worse. In a sense, Pareto's own trajectory parallels Herbert Spencer's. Spencer entered adult life when classical liberalism was on the winning side: the Corn Laws had just been abolished; the spirit of the age was that of liberal reforms; more government retrenchment seemed possible if not likely. Spencer's understanding of social evolution as unfolding differentiation and increasing complexity did not necessarily require but went well with such attitudes.

An older man, in the 1880s, Spencer came to think that "most of those who now pass as Liberals, are Tories of a new type." If liberalism used to be about freeing people from government intervention, later "liberalism has to an increasing extent adopted the policy of dictating the actions of citizens."

In "The New Toryism," the first of the essays that he put together in The Man versus the State, Spencer offers a charitable explanation of the phenomenon:

For what, in the popular apprehension and in the apprehension of those who effected them, were the changes made by Liberals in the past? They were abolitions of grievances suffered by the people, or by portions of them: this was the common trait they had which most impressed itself on men's minds. They were mitigations of evils which had directly or indirectly been felt by large classes of citizens, as causes to misery or as hindrances to happiness. And since, in the minds of most, a rectified evil is equivalent to an achieved good, these measures came to be thought of as so many positive benefits; and the welfare of the many came to be conceived alike by Liberal statesmen and Liberal voters as the aim of Liberalism. Hence the confusion. The gaining of a popular good, being the external conspicuous trait common to Liberal measures in earlier days (then in each case gained by a relaxation of restraints), it has happened that popular good has come to be sought by Liberals, not as an end to be indirectly gained by relaxations of restraints, but as the end to be directly gained. And seeking to gain it directly, they have used methods intrinsically opposed to those originally used.

Spencer considers this a confusion as being originated by the very successes of liberalism itself. He spots serious intellectual errors, like the idea that popular government changes the nature of government, so that a democracy's limitations of individual liberty are no longer considered akin to limitations, and points them out. He is certainly alert to the importance of special interests, and he certainly thinks of the importance of irrationality and pre-rational attitudes, but sees the fallacies of contemporary liberals as conceptual mistakes and therefore tries to correct them.

Pareto sensed continental Europe to be in the midst of a similar trend—and perhaps a stronger one, for Italy and Germany never had a Richard Cobden. But he offered a slightly different explanation. Let me refer to a 1903 article, significantly entitled "The Eclipse of Freedom":

Liberal doctrine is optimistic, as it presupposed men can cease pillaging each other. Before experience decided the issue, this hope could appear something else than a chimerical one, but facts shew at an advantage that, at the very least, the times are not ripe for its being made a reality. Thus, whoever cannot directly oppose being a victim of plunder, cannot but follow the example he is provided with and take after the dog that started with guarding his master's meal and then—realising he was too weak to do it—ended up with stealing his share. [Pareto 1903, 388-89]

So in a sense the problem lies with the very political game: if you take part in it, you can't but end up playing by the rules. And the rules entail a competition for other people's resources that liberalism should have limited but ultimately failed to curb.

What underpins this view is a neatly classical-liberal conception of freedom. Pareto quotes Gustave de Molinari, one of his favorite economists, pointing out that "as liberty decreases, so decreases the fraction of one's own goods that the individual can freely dispose of, and grows the fraction available to the government." (Pareto 1904, 399)

This view of liberty is basically the liberty of being left alone. And such liberty was challenged, as the century was turning, by those very parties that traditionally claimed to be its champions. One theme Pareto held dear, and this sounds truly prescient in times like ours, is that of freedom of expression being limited in the name of freedom of expression. Advocates of secularism calling for government meddling with church activities; "free thinkers" calling for punishment of university professors who "dare challeng[e] the benefits of divorce" (Pareto 1904, 403), to Pareto, all of this sounded awfully similar to conservatives limiting freedom to buy alcohol or shopping on Sundays.

If I must find a point of disagreement with Professor Wagner, it is that I do not think that Pareto ever sounded "aloof and even cold." He was a student of political passions, and a passionate man too. He wanted to be "scientific" and cold in dissecting politics, but was also loyal to a concept of liberty that he thought was hopelessly out of fashion , as self-styled liberals do not believe in it anymore: :

If we attempt to more or less roughly appraise how the notion of liberty changed in time, we'll see that in the times when they are in a state of subjection—and the countries where they currently are subjugated—popular parties call liberty the freedom of acting, as this freedom benefits their fellow subjects; whereas when they are the masters—and in the countries they rule—they call liberty the banning of action, as this prohibition benefits the rulers. [Pareto 1904, 406]

This seems to me to be a profound remark that considers the "statist" evolution of liberalism as a result of democratization and the enlargement of the franchise, causes that liberals of the old kind they themselves championed without foreseeing their ultimate, unintended consequences. It is in this context that "all past privileges are revived again" (Pareto 1904, 408): people considered entitlements of the sovereign arrogant and unbearable when such sovereign was clearly identifiable with a king or a small coterie of aristocrats. But when all people can somehow partake of those same entitlements, their judgment changes and the idea that we should do away with the entitlements fades.

The greatness of the Italian theory of the ruling class lies precisely here: in understanding the basic dynamics of politics as something which is not truly modified by changes in the way in which politics seek legitimization. This was a bold idea, particularly when democracy was younger and perhaps more radiant and sincere.

A side note: on Facebook, Bill Evers reminded me of the following quote from Murray Rothbard : "Vilfredo Pareto was a militant laissez-faire liberal and battler for free trade, heavily influenced by the French anarcho-capitalist Gustave de Molinari. Despairing of freedom and the free market after the turn of the twentieth century, Pareto retreated into cynical critiques of political action, but he was never not interested in political economy." (Rothbard 1993) With this reference to "cynical critiques of political action," this quote seems quite apropos to our discussion -- it indeed evokes its very title. In his History of Economic Thought, Rothbard indeed calls Pareto a "pessimistic follower of Gustave De Molinari." (Rothbard 2006, 455) A realist is a pessimist in the eye of an optimist, I suppose. But no matter what you call it, a realist or pessimist is equipped with something an optimist often lacks: a tragic understanding of politics. This, I think, reinforces Giandomenica's suggetion to consider Pareto as a modern moralist.

Endnotes

[6.] Rosolino Candela rightly reminds us of Bastiat's "What Is Seen and What Is Unseen." That little essay lies deep at the heart of Pareto's own understanding of economics. Once Pareto claimed that "Bastiat's Ce qu'on voit et ce qu'on ne voit pas [what is seen and what is unseen] emerges from" Walras's formulas. (Pareto 1895, 424). I hope my economist friends and fellow discussants may pick up the point.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.