Liberty Matters

The Standing Army-Militia Debate: A Legacy that Endures

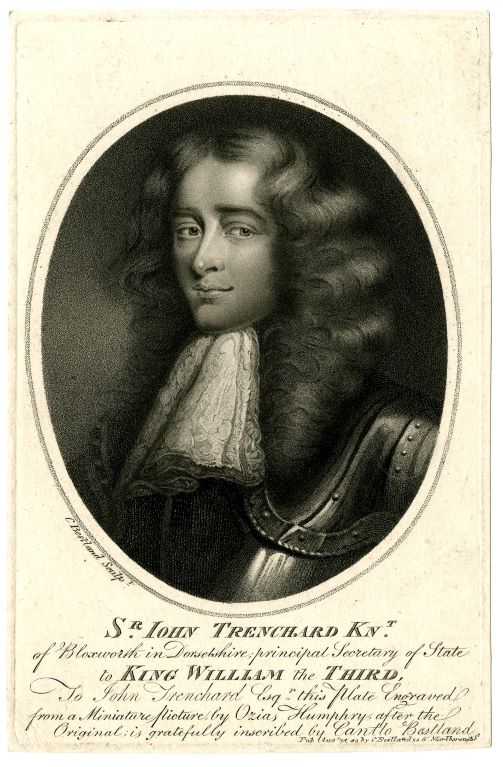

It’s incredible what jumps out at you on reading the anti-standing-army tracts of the likes of Thomas Gordon and John Trenchard. To David Womersley’s reflections on “Trenchard and the Opposition to Standing Armies,” I would like to add a few points prompted by Gordon’s A Discourse of Standing Armies (1722)[10] to suggest that the old debates made a difference at the founding of the American Republic and continue to resonate today.

Let’s first consider the debate with the backdrop of the Declaration of Rights of 1689, which stated as necessary for vindicating the “ancient rights and liberties” of Englishmen:

6. That the raising or keeping a standing Army within the Kingdom in Time of Peace, unless it be with Consent of Parliament, is against Law. 7. That the Subjects which are Protestants, may have Arms for their Defence suitable to their Condition, and as are allowed by Law.[11]

The limitations were clear enough – the restraint on standing armies applied only “within the kingdom,” not (as Professor Womersley notes) in places like Ireland, or for that matter in any of the colonies. How else could there be a British Empire without armies abroad? Further, the prohibition applied only in time of peace, and even at one point Gordon “confess[ed], an Army at last became necessary, and an Army was raised time enough to beat all who opposed it....” Finally, an army could be raised only with the consent of Parliament, with no further impediment.

As to those who “may have arms for their defence,” it was limited to Protestants, and it would be “suitable to their conditions and as allowed by law.” As the Declaration had recited, James II violated the rights of Englishmen by causing Protestants “to be disarmed at the same time when Papists were both armed and employed contrary to law.” Instead of allowing all good subjects to be armed, the right did not apply to Catholics, who would be limited to keeping arms for defense of the person or house with the consent of the justice of the peace.[12]

Although speaking on the context of armies, Gordon’s following remark also applied to the subjects: “A Protestant Musket kills as sure as a Popish one; and an Oppressor is an Oppressor, to whatever Church he belongs: The Sword and the Gun are of every Church, and so are the Instruments of Oppression.” That applies as much to a society wherein segments of the populace are disarmed based on politics, class, or race, just as much as it applies to Gordon’s intended situation of an armed government that oppresses a populace based on its religion. Again, consider Gordon: “If we are to be govern’d by Armies, it is all one to us, whether they be Protestant or Popish Armies; the Distinction is ridiculous, like that between a good and a bad Tyranny....”

In relation to that point, the tract writers of the period had a knack for using the English language in an animate manner that eludes us today. Consider Gordon’s reference to politicians (and this applies equally now) who distinguish “oppressive Oppression” – that of their opponents – from their own “unoppressive Oppression.” Or this jewel: “Oliver Cromwell headed an Army which pretended to fight for Liberty, and by that Army became a bloody Tyrant; as I once saw a Hawk very generously rescue a Turtle Dove from the Persecution of two Crows, and then eat him up himself.” As we say today: I’m from the government and I’m here to help you.

It is difficult to overestimate the influence of anti-army protagonists on the American Founders, who defeated the most powerful army in the world. Recall that the English Declaration denounced standing armies “within the kingdom,” and the Crown didn’t consider colonies to have that status, but the Americans thought they were entitled to all rights of Englishmen. Again, consider Gordon: “’Tis certain, that all Parts of Europe which are enslaved, have been enslaved by Armies, and ’tis absolutely impossible, that any Nation which keeps them amongst themselves, can long preserve their Liberties; nor can any Nation perfectly lose their Liberties, who are without such Guests....” Compare that with James Madison’s reference to “the advantage of being armed, which the Americans possess over the people of almost every other nation,” and his followup comment: “Notwithstanding the military establishments in the several kingdoms of Europe, which are carried as far as the public resources will bear, the governments are afraid to trust the people with arms.”[13]

That same James Madison drafted a Constitution that delegated power to Congress “to raise and support armies.”[14] Contrast that with the purist Gordon, who presumed that “no Man will be audacious enough to propose, that we should make a Standing Army Part of our Constitution....” George Mason and his Anti-Federalist colleagues failed to have the Constitution amended to require that two-thirds of both houses of Congress would be necessary to keep up a standing army.[15] But they succeeded in causing recognition of a counterpart, and Madison’s pen obliged: “A well regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed.”[16]

So no matter the discrepancies between the Gordon-Trenchard Weltanschauung and the historical development of the real world, which Professor Womersley rightly pinpoints, the dangers of a standing army and the need for a balance of power in a polity to keep the army in check are ideas that resonated in real-world America. True, Gordon warned Great Britain “To meddle no farther with Foreign Squabbles,” just as Jefferson advocated “peace, commerce and honest friendship with all nations – entangling alliances with none.”[17] Neither the United Kingdom nor the United States followed those dictates, and they built standing armies to intervene around the world.

Not that this was always a bad thing, given the need to stop the Axis in World War II. That conflict offered an occasion to revive the militia concept which had gone dormant. After decades of depriving her citizens of arms, with Dunkirk the U.K. couldn’t give them out fast enough to her citizen Home Guard to allow them, as Churchill said, to help fight the expected Nazi invaders on the beaches, the landing grounds, in the fields, and in the streets.[18] In America, as the young men went to war, those remaining who were hunters and sports shooters brought their guns to join the State Protective Forces and guard against sabotage and subversion.[19]

The old debates were echoed in the 2008 decision of the U.S. Supreme Court holding that the Second Amendment, with its militia and arms right clauses, protects an individual right to keep and bear arms, rendering the District of Columbia’s handgun ban void. Justice Scalia wrote that the militia was thought to render large standing armies unnecessary and to enable a trained, armed populace to resist tyranny. Recognition of a right to have arms not only made that possible, but also reflected the value placed on the right by Americans for self-defense and hunting.[20]

Gordon asked, “Are we never to Disband, till Europe is settled according to some modern Schemes?” Some may have thought the European Union would provide such a utopian scheme. But much danger lurks from foreign terrorism originating outside of Europe and which is increasingly home grown in Europe. No army can protect citizens from random, surprise attacks. A long European history of mistrusting the people with their own firearms for self-defense is exacerbated by the E.U.’s drive toward an almost total prohibition of private arms. “When the People are easy and satisfy'd, the whole Kingdom is his [the King’s] Army,” wrote Gordon. But there can be no Army of a disarmed people.

As Professor Womersley states, Machiavelli extolled the virtues of Rome’s citizen militia. That tradition, Machiavelli added, was inherited by the Swiss, who being armed enjoyed great freedom. The pike and the broadsword were preferred “by the Swiss; since they are poor, yet anxious to defend their liberties against the ambition of the German princes – who are rich and can afford to keep cavalry, which the poverty of the Swiss will not allow them to do – the Swiss are obliged to engage an enemy on foot, and therefore find it necessary to continue their ancient manner of fighting in order to make headway against the fury of the enemy's cavalry.”[21]

The theme that a small country like Switzerland, through its armed populace, could beat back all the great armies of the European monarchs was heralded by Colonel John A. Martin in his A Plan for Establishing and Disciplining a National Militia in Great Britain, Ireland, and in All the British Dominions of America (1745) and by Patrick Henry, arguing in the Virginia ratifying convention of 1788 against a federal government with expansive powers.[22] Surrounded by the Axis in 1940, the Swiss dissuaded a Nazi invasion by her people in arms and her Alps. Despite the efforts of the Socialists and Greens to abolish it, to this day Switzerland maintains a militia army.

Gordon and Trenchard would have been proud.

Endnotes

[10.] Thomas Gordon, A Discourse of Standing Armies; shewing the Folly, Uselessness, and Danger of Standing Armies in Great Britain, 3rd edition (London: T. Warner, 1722). </titles/1719>. All quotations to Gordon are from this source.

[11.] 1 Wm. & Mary, sess. 2, c. 2 (1689).

[12.] An Act for the Better Securing the Government by Disarming Papists and Reputed Papists, 1 W.&M., sess. 1, c. 15 §4 (1689).

[13.] The Federalist No. 46, in The Federalist (The Gideon Edition), Edited with an Introduction, Reader’s Guide, Constitutional Cross-reference, Index, and Glossary by George W. Carey and James McClellan (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2001). </titles/788>.

[14.] U.S. Constitution, Art. I, § 8. In James McClellan, Liberty, Order, and Justice: An Introduction to the Constitutional Principles of American Government (3rd ed.) (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2000). </titles/679#McClellan_0088_993>.

[15.] 9 Documentary History of The Ratification of the Constitution 823 (Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1990).

[16.] U.S. Constitution, Amend. II. </titles/679#lf0088_head_192>

[17.] First Inaugural Address, 1801, in Thomas Jefferson, The Works of Thomas Jefferson, Federal Edition (New York and London, G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1904-5). Vol. 9.</titles/757#Jefferson_0054-09_302>.

[18.] Speech of June 4, 1940, to House of Commons. See S.P. MacKenzie, The Home Guard (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995).

[19.] E.g., Report of the Adjutant General for 1945 23-24 (Richmond, VA: Commonwealth of Virginia, 1946).

[20.] District of Columbia v. Heller, 554 U.S. 570, 598-99 (2008).

[21.] Machiavelli, The Art of War, E. Farneworth transl. (Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill, 1965), 46-47. See Bernard Wicht, L’idée De Milice et Le Modèle Suisse Dans La Pensée De Machiavel (Lausanne: L’Age d’Homme, 1995).

[22.] See Halbrook, “The Swiss Confederation In the Eyes of America’s Founders,” Swiss American Historical Review 32 (Nov. 2012).

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.