Liberty Matters

Liberal Pluralism and Ideological Instability

I too would like to thank Jacob Levy for his thoughtful and helpful responses to my comments and those of my fellow conversationalists. Through these responses he has more clearly defined his argument in RPF and certainly helped me better to understood where exactly he stands. One specific point he makes is well worth recalling; namely, that “the gradual evolution of ancient constitutionalism into modern pluralist liberalism was the work of theorists after Montesquieu to think about pluralism without privilege.” I had never thought about it this way before, but of course, this being the case, it helps us to explain why this tradition of thinking did not perish, along with much else of worth, in the cataclysm that befell the ancien régime in 1789. If Tocqueville is probably the best example of how this development occurred, there are many others: the point is that the claims of associational life were relocated to a new and emerging democratic society. For this we have much to be thankful for.

However, the thing that most impresses me in RPF and in Jacob Levy’s comments is his insistence, as expressed in his first reply, that, although liberal thinkers have shared a deep attachment to freedom, “their basic sensibilities about where to find threats to it and how to defend it often pointed them in opposite directions.” This in turn leads him to a conclusion that also merits being repeated: “for lots of purposes in political and social theory we need to make do with tendencies and generalizations and institutional approximations.” As we know, most contemporary political theory does not heed this advice, and it is all the poorer for it.

Clearly, much of the conversation has followed from Jacob Levy’s first rejoinder and his remark there that his argument about pluralism has to be seen against a “backdrop of the Weberian State.” As he concedes, in RPF he did not emphasize enough that neither ancient constitutionalism nor its modern pluralist version were calls to “abolish central authority in favor of smaller units.” This allows him to claim that Gary Chartier has misunderstood where he stands and also to reject David Hart’s observations about the predators who abuse the power of the modern bureaucratic state. More intriguingly it encourages Jacob Levy to describe him as a “non-anarchist.”

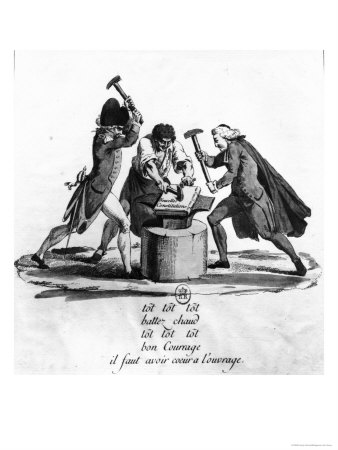

I can understand what Jacob Levy means by this – the state is a social fact, etc. – although this was not a concept with which I was familiar. But it did make me think of where I started more years ago than I care to remember: studying thinkers like Georges Sorel and the wider anarcho-syndicalist tradition in France. First, we should note that, unlike Jacob Levy, these people quite definitely did not exclude commercial associations from their considerations. Far from it, in fact. For them, we were first and foremost homo faber, and the primary intermediate institutions they focused upon were trade unions and cooperatives. As Gary Chartier observes, it is odd that later liberal or proto-liberal writers seem to have ignored this very important dimension of the picture. After all, for all our contemporary preoccupations with gender and ethnicity, we have come increasingly to define ourselves not by what we believe but by what we do. Second, I was always troubled when my French acquaintances characterized Sorel as a liberal. Surely, he was a Marxist! But I quite quickly saw that Sorel was a pluralist – he was, for example, virulently opposed to the French state’s attacks on the Catholic Church after the Dreyfus Affair – and I came to see that the one abiding theme that tied his voluminous writings together was a detestation of the Jacobin state. He also loathed Rousseau!

I mention this because, when I looked beyond Sorel to his many very intelligent admirers, I was struck by the remarkably diverse political journeys they were subsequently to take. Sorel himself developed an enthusiasm for Lenin (naively believing that Lenin genuinely thought that all power should go to the soviets); some came to admire Mussolini; others, the corporatism of the Vichy regime; others still became left-of-center reformists; and some (very few) remained true to their original positions. But, odd as it might sound, all shared a detestation of the rationalism of the Jacobin state and all believed in the virtues of a rich associational life.

In other words, at the heart of this particular form of what I am now ready to describe as a liberal pluralism lay a fundamental ideological instability. Now, it could be the case that Jacob Levy’s endorsement of the Weberian state enables him to avoid such a fate and as such rest secure in his attachment to views he briefly describes as being “popular among American left-liberals.” If so, all well and good. But I too believe in a robust freedom of association, religious freedom, and cultural freedom, and just about the last thing I would wish to be described as would be an American left liberal! This is why I (rather hopefully) suggested that there might be a bit of Michael Oakeshott lurking somewhere in the recesses of Jacob Levy’s thinking.

Again, Gary Chartier is right to comment on the way Jacob Levy emphasizes the “inescapable ambiguity of judgment and the unavoidability of trade-offs,” but, following on from the above, I wonder if the whole tradition of liberal pluralism that Jacob Levy has so skilfully recovered is not prone to the kind of ideological instability I mention. It certainly has taken its adherents to some very strange places, not the least of which was Acton’s support of the Confederate states. Not only might this explain why this rich tradition of thinking required archaeological excavation, but also why, for all our agreement, Jacob Levy might look one way and I look another.

Whether this be true or not, I look forward to continuing this conversation when Jacob visits London next week!

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.